r

e

v

e

s

«Photography is a new grammar and ethics of seeing»[1]

If photography is a grammar of looking, in order to orientate ourselves into a global, complex and hybrid world, where different languages endlessly meet and clash, it would be ideal to enrich our visual vocabulary as much as possible, to include as many different visions we can. Unfortunately, there are still few contexts in which the language of photography tries to embrace extra-European views as autonomous visions of the world.

As concerns African photography, the geographical label, often used as cultural marketing, actually incorporates many different worlds, sometimes very hard to define. If, as Heidegger states that «the being must be considered related to the language we speak and which in turn speaks to us, conditioning our possibilities of world experience»[2], we can assume that for those who had to submit to the «language of power» and its imagery, the creation of their own visual language had been an important step towards the (re)construction of their own identity.

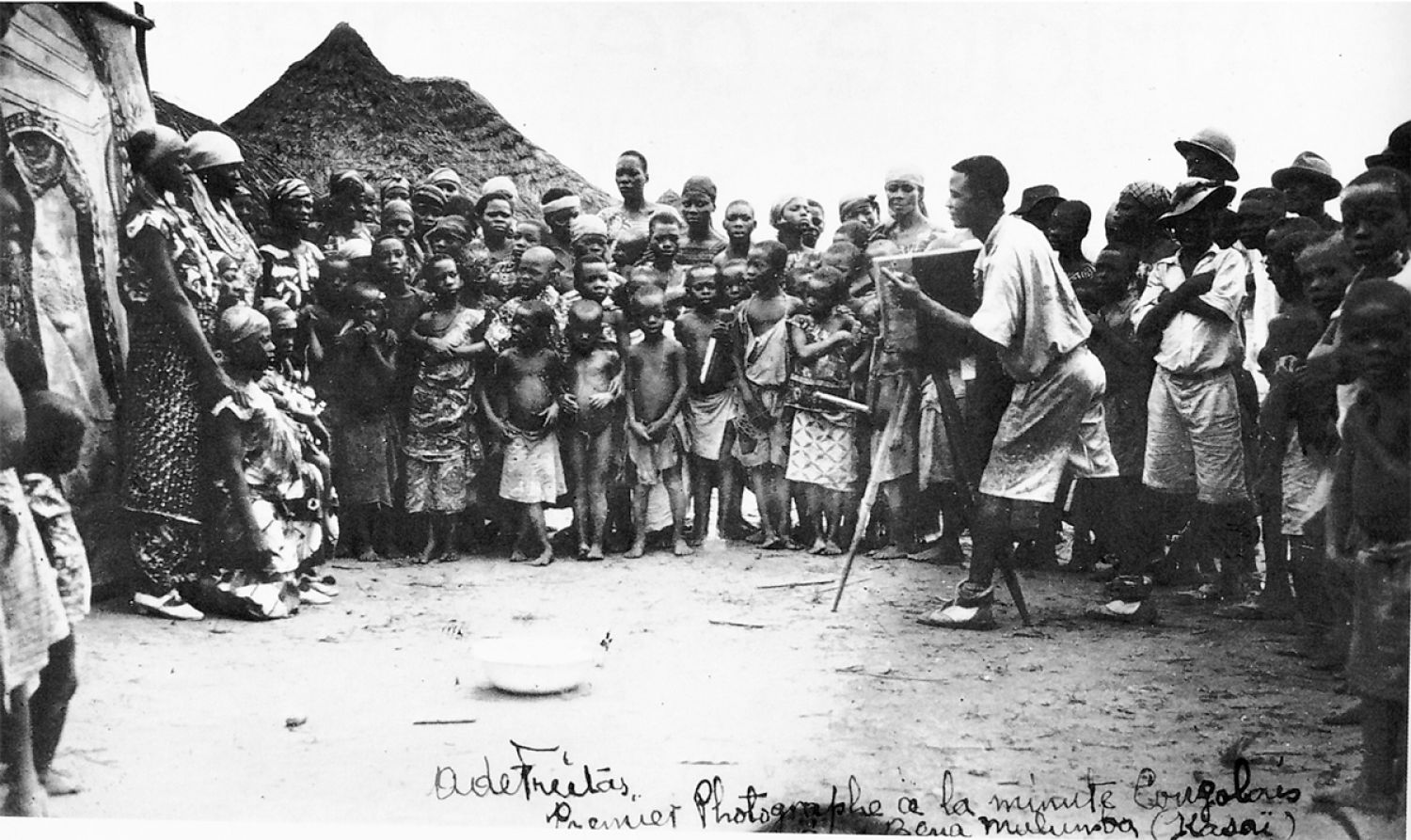

It is hard to adequately define the arrival of Europeans with their technological and cultural baggage in Africa, but considering that colonialism utterly implies tradition means an underestimation of African’s own skills to act and react. In such a process of the interchange of knowledge, technologies, and identities, what was new not only replaced what was old, but also merged with it, into a unique form made out of an original synthesis. On the other hand, considering colonialism as a single episode in history means to underestimate all those tools industrial civilization brought to populations who ignored them. Among those tools, photography was undoubtedly one of the most powerful and compelling. If we consider McLuhan's words, imagining the camera as an extension of the eye or even its amplification, we can figure out how the «western view,» driven by the camera, generated in the colonized peoples an awareness of their own image and its distortion.

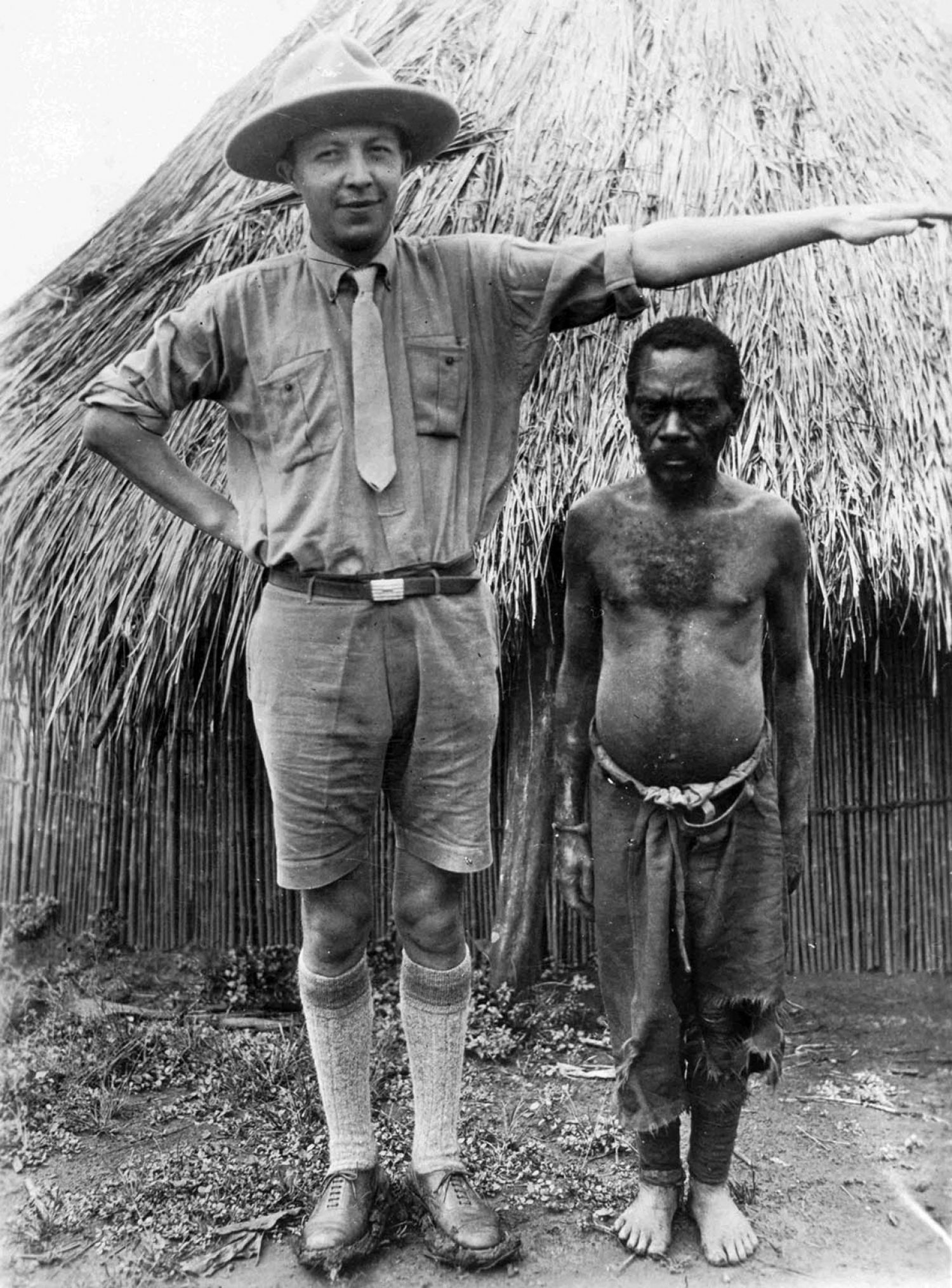

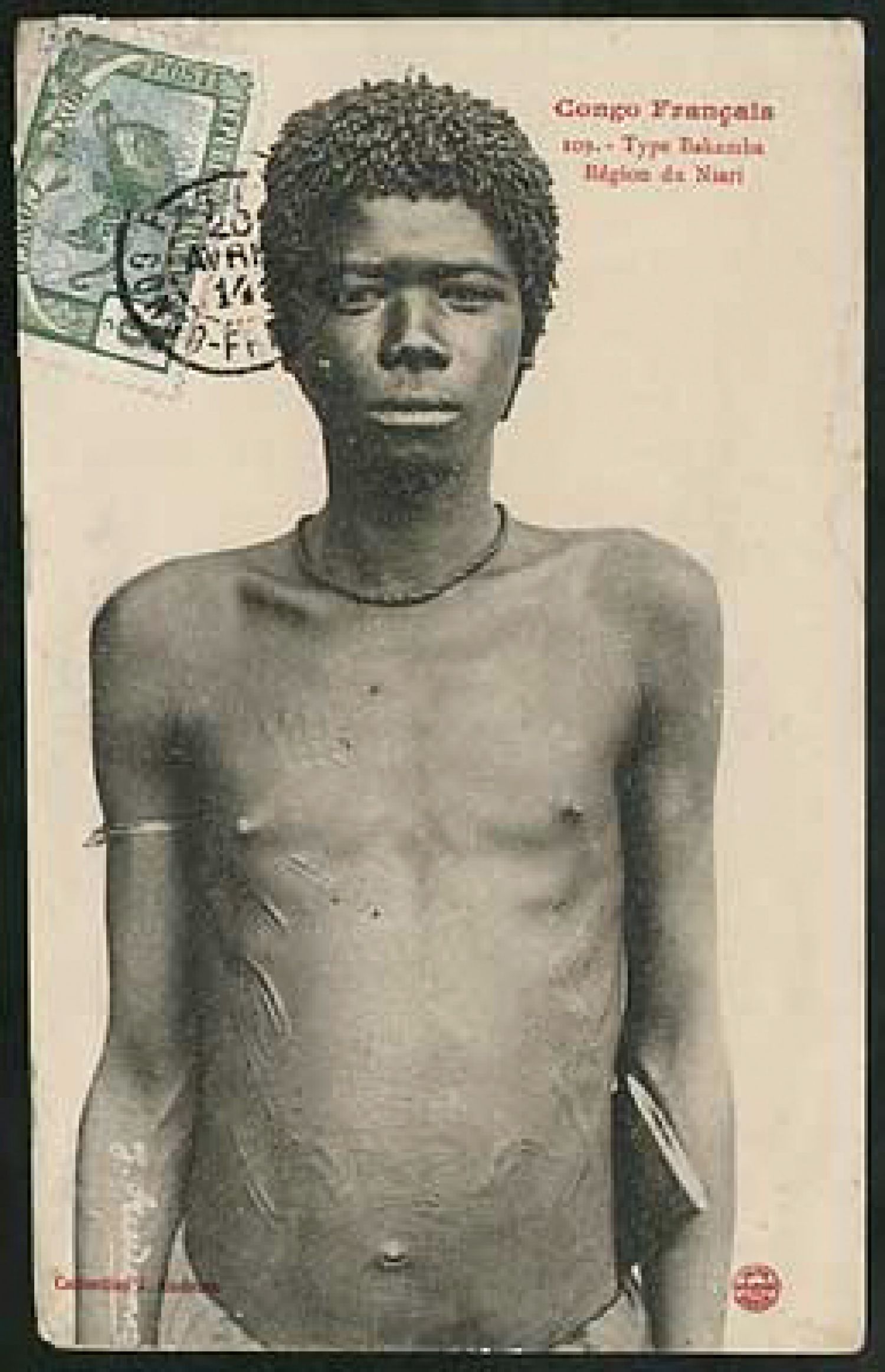

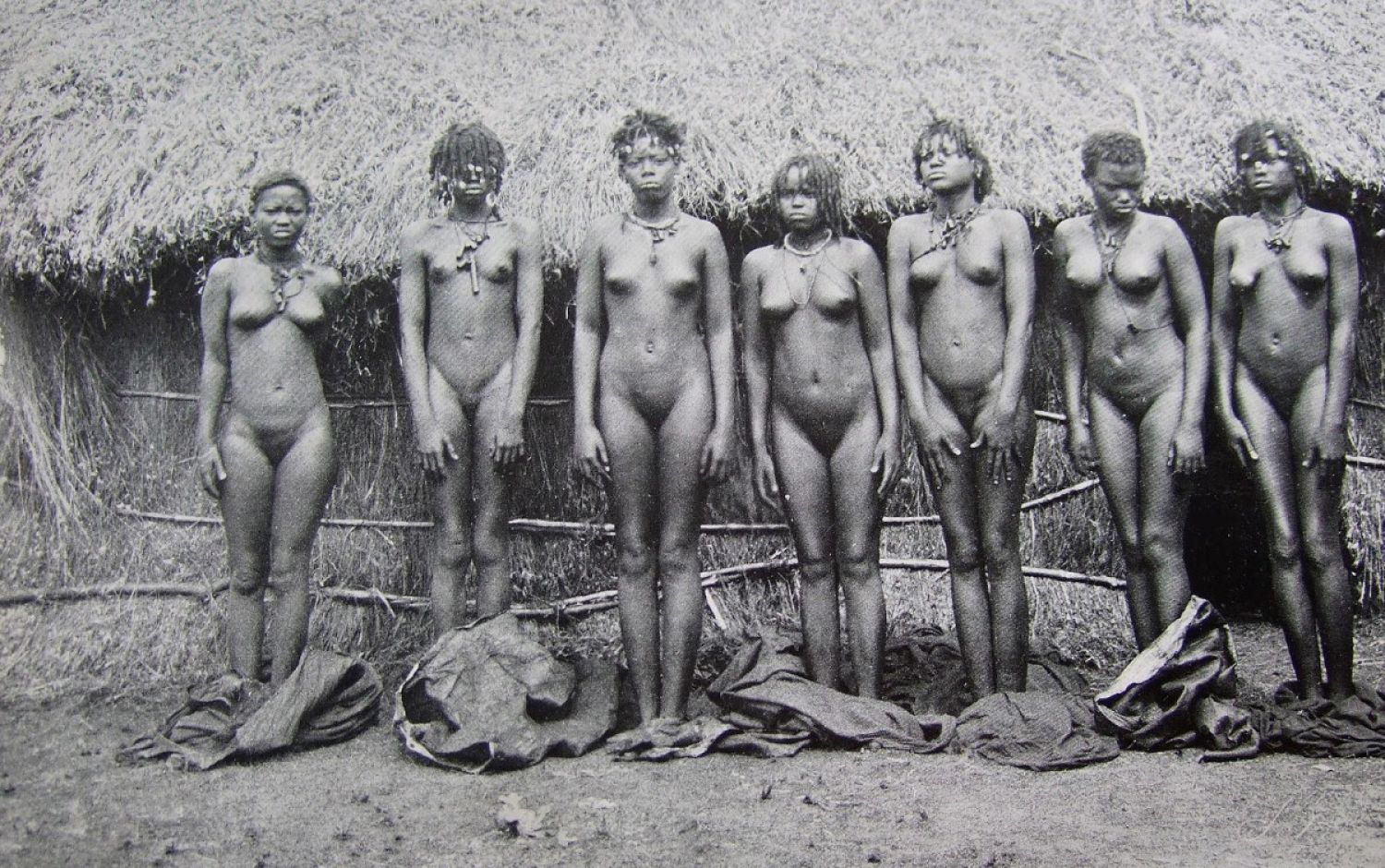

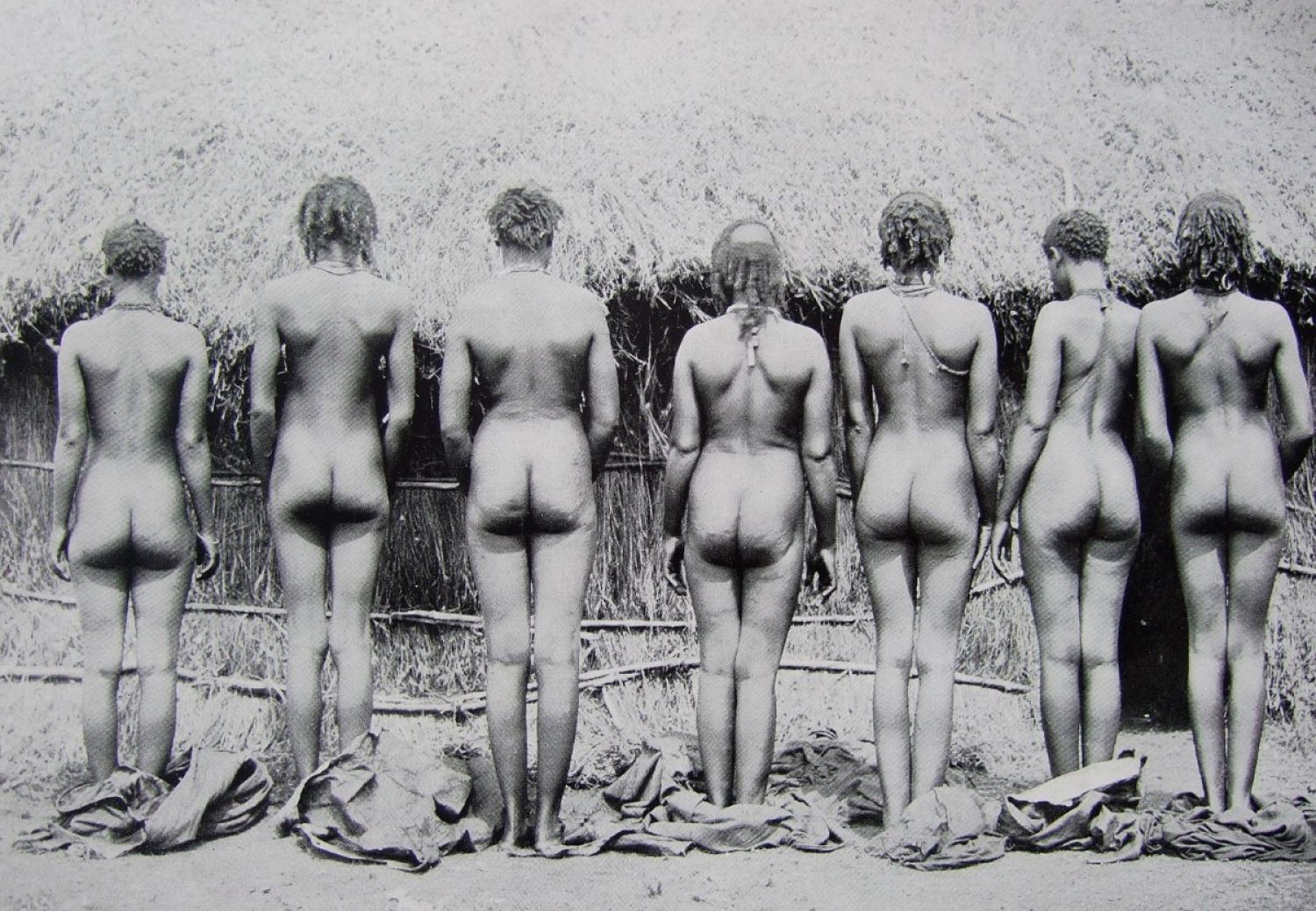

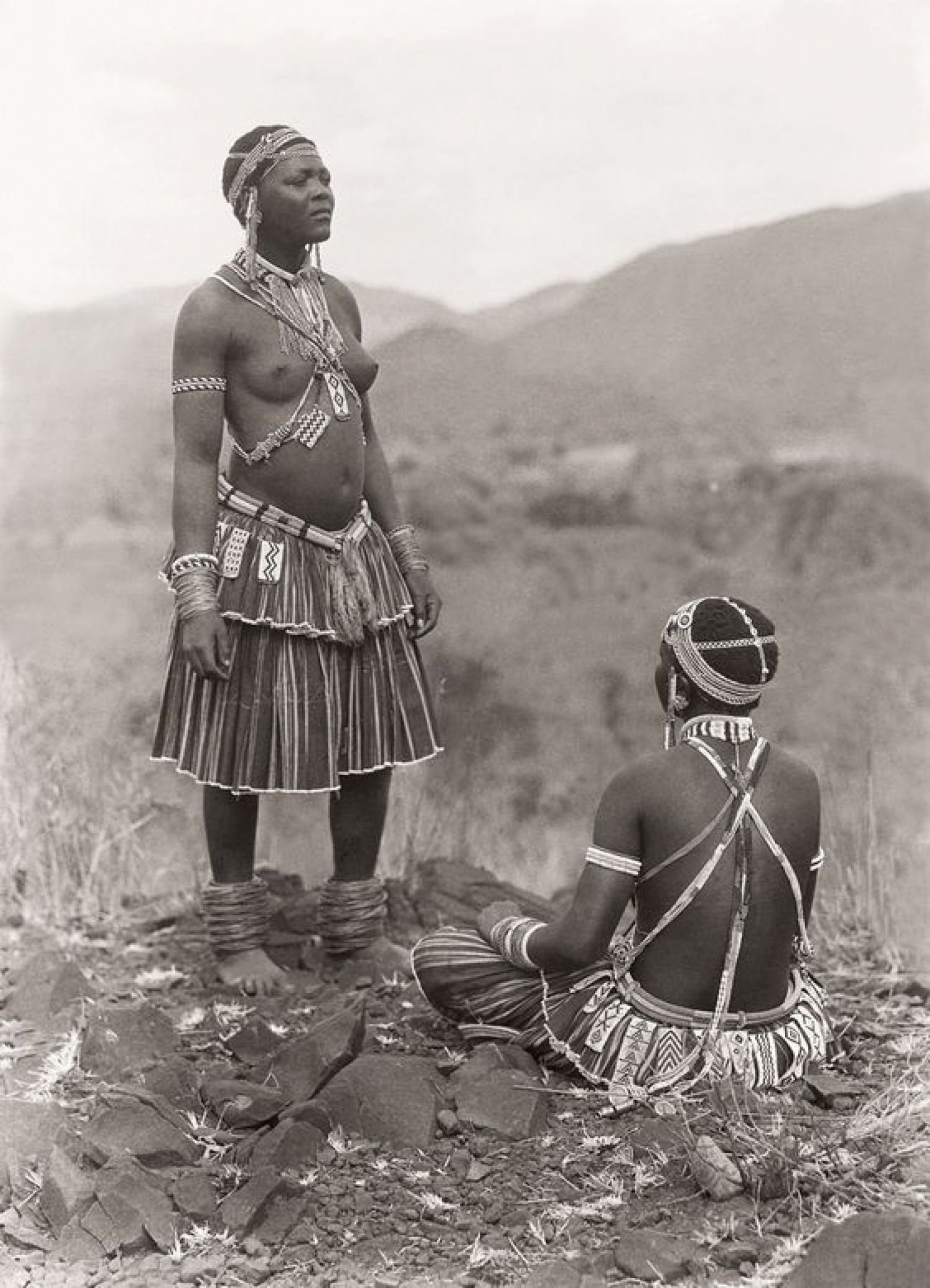

From the beginning, Africans (and more generally native peoples of European colonies) were mostly represented in a typological, racial and racist perspective, that shifted the focus to crystallized features whether physical or «ethnic»: distinctive signs, styles of clothing or accessories, and techniques of body manipulation.

The colonial intent was to overlook all the changes and transformations that had taken place on the continent over the course of history, by fixing iconic images of what Africa was and should be for Westerners: Africa, the primeval continent, tribal, backward because of too many different ethnic groups struggling among themselves. This was considered a perfect justification for the intervention of Europeans. In this process, photography provided a tangible and functional proof, since the visual impact immediately made alive, real and comprehensible the rhetoric of alterity.

McLuhan still helps us to give a more precise definition of this process of image manipulation by photography. He thus writes: «all media are active metaphors in their power to translate experience into new forms […] The word ‘metaphor’ is from the Greek meld plus phérein, to carry across or transport […] Each form of transport not only carries, but translates and transforms, the sender, the receiver, and the message».[3]

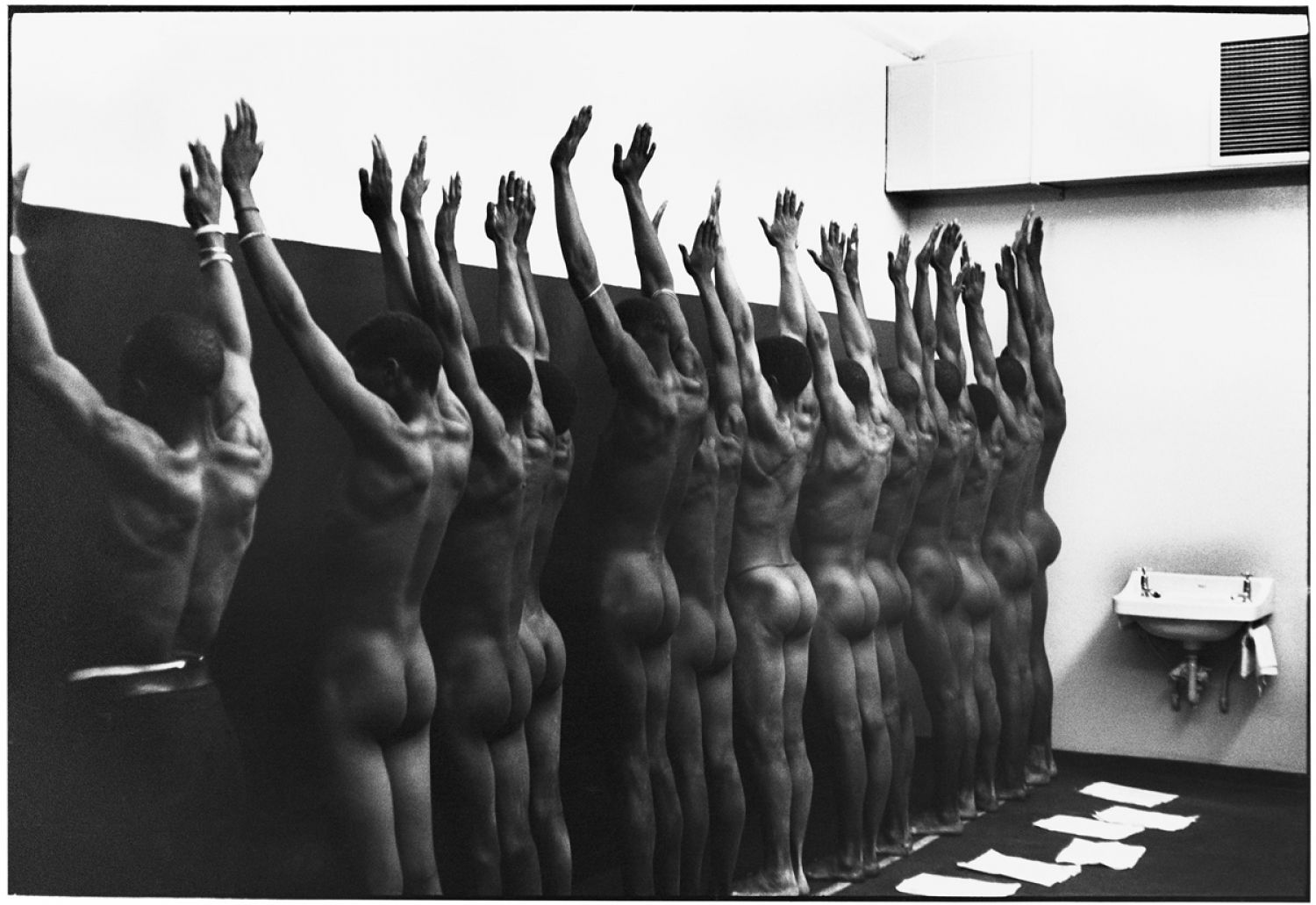

Photography, therefore, was not merely a testimony of change, but it was a means to that very change: the portraits, the poses, the educational use of images for pedagogical purposes, were intended as a proof of the progress of European civilization. It was a model for taming the natives and transforming them into «docile bodies».[4]

The ever more conscious use of the medium by African photographers, in the exploration and documentation of the world and of themselves, would thus represent the awakening of an increasingly aware gaze, born out of the comparison, the interaction and the confrontation with an external vision.

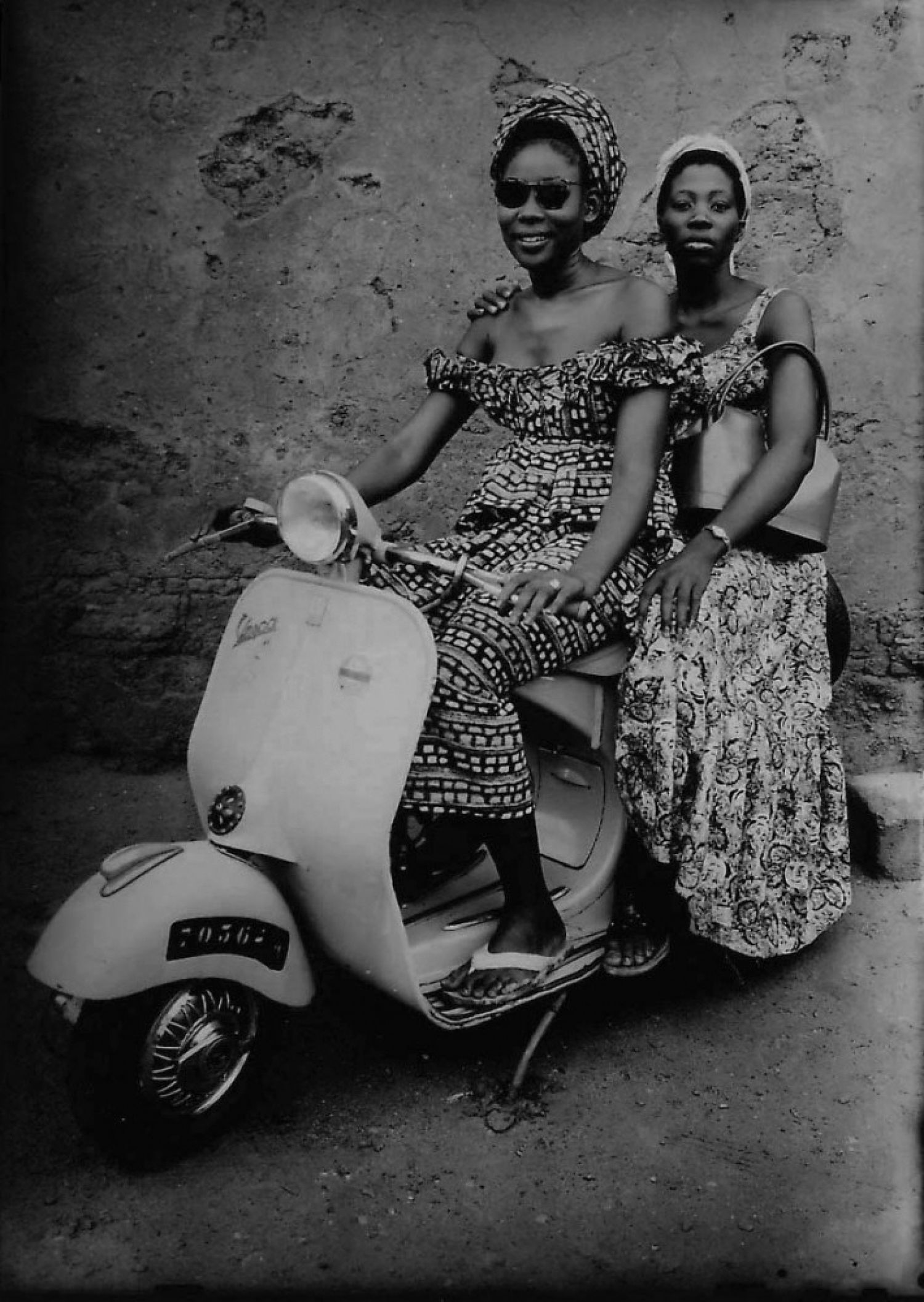

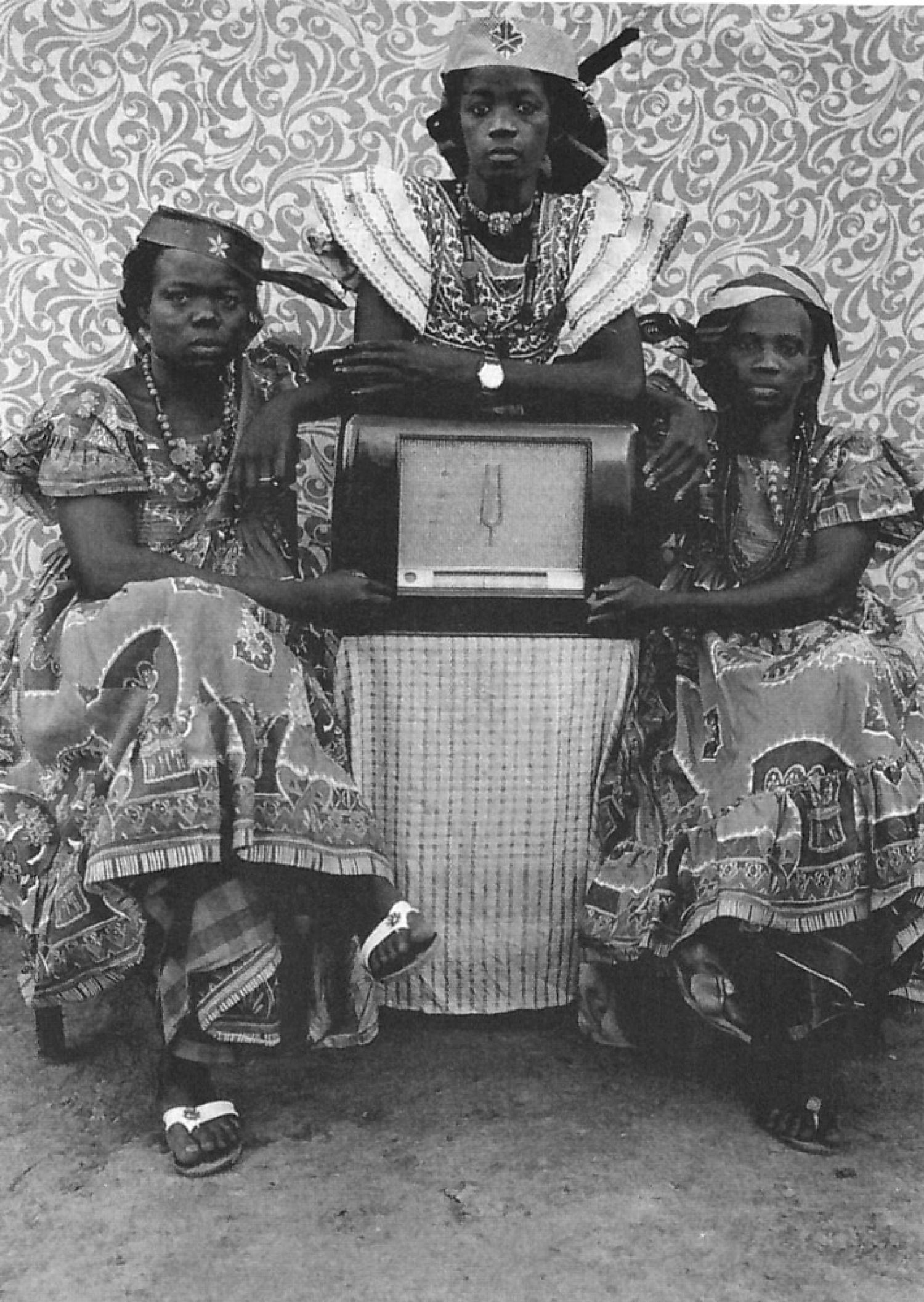

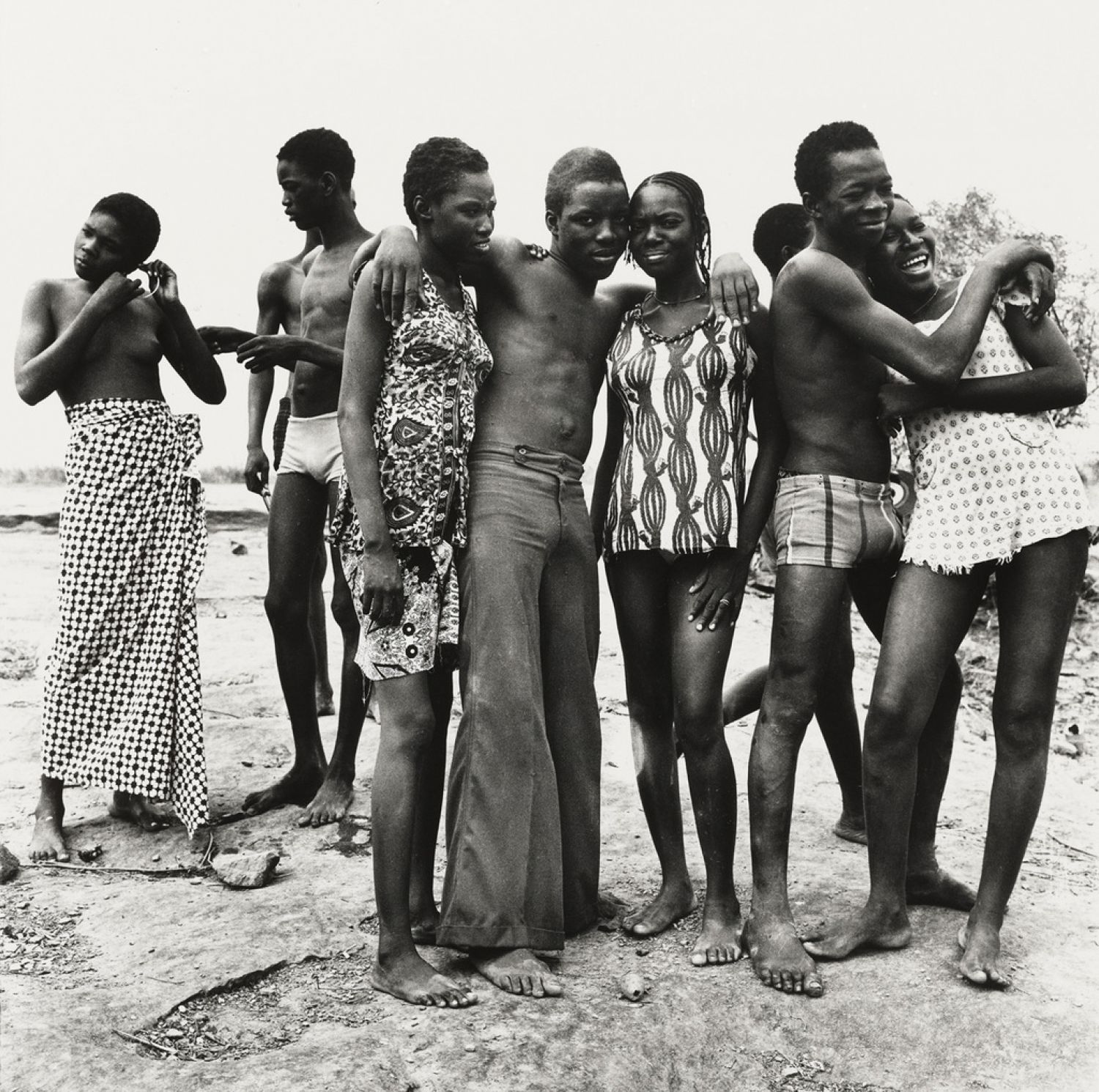

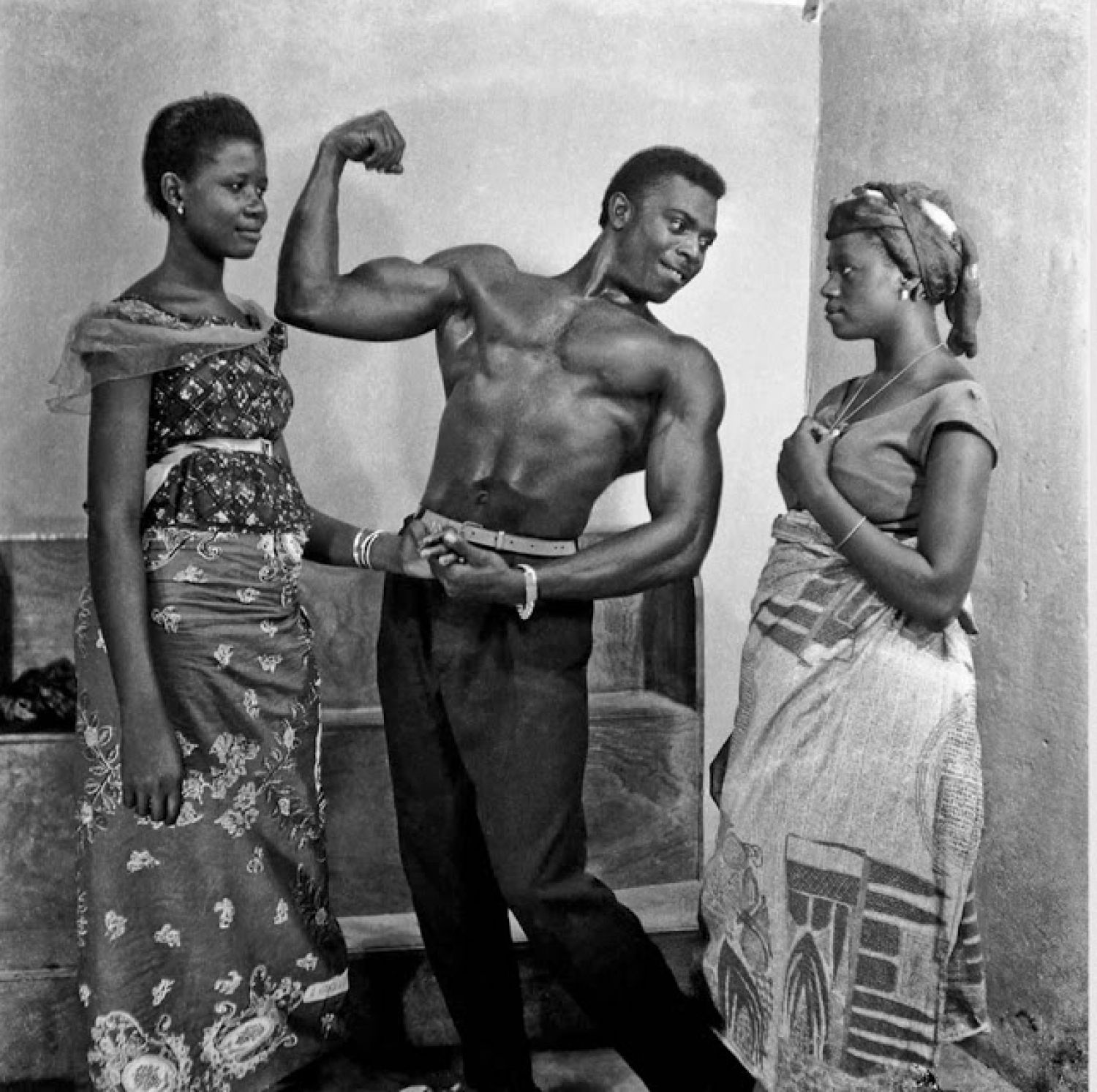

After a first contact, that we can call as a «visual pidgin» borrowed from European codes, Africans began to have control and power over the photographic medium and to develop a new awareness of both national and individual consciousness, between the two World Wars. Photography, used to create and fix one’s image, became pervasive within a culture where «ritualized self-representation was yet a great art of daily life»[5]. The reclaiming of the personal image, once used merely to resemble a model, acquired social and spiritual value, and symbolized the chance to be represented in a chosen, and no longer imposed, reality. Indeed «the ritual of reinventing the self» became in a short time «the unique and most important structure of support for photography in Africa»[6], slowing down the rise of so-called social photography.

The vast majority of African photographic archives show an extensive use of vernacular photography until the 1970s: a considerable number of portraits in different settings frame the documentation of significant ritual events celebrated in the community.

Photography was concerned with the dreamt sociability and defined the place subjects had or desired to have within it. The individual self did not exist outside of the shared values that represented it.

Vernacular images contrast with the official ones, which in the Sixties (during the independence process and the formation of national states), proudly displayed and celebrated icons and totems of power.

Within the African context, a sharp and socially concerned awareness manifested itself for the first time in South Africa, where colonial events were entirely different from those of the rest of the continent. If photography emerging in this context cannot be defined merely as the result of a political process, it cannot even be considered apart from it. While South Africa was establishing the structure of the segregationist regime, the rest of Africa was in the process of decolonization. In the historic moment when Europe and the whole world critically reflected on recent and past persecutions of minorities', in South Africa was forming the first group of photojournalists involved in the denunciation of abuse and injustice against black people.

We can think of social photography in South Africa as a complex set of ideas and practices that could be defined, with a fashionable term, as glocal: global and modern, but at the same time rooted in the South African context and history.

In this analysis of photographic works, three seminal moments emerge in the evolution of the «South African style»: the remarkably early propagation of photography due to intense trade and cultural exchanges with England; the renunciation of romantic pictorialism for a more direct realism and therefore an early development of documentary photography. The examples chosen do not claim to be exhaustive with regard to the whole South African photographic scene, but they summarize complementary visions of the same stereotype, and help us to think from different perspectives about the ever-elusive concept of «mental colonization» and «re-appropriation» and hence about the increasing use of photography as a means of social denunciation.

1.

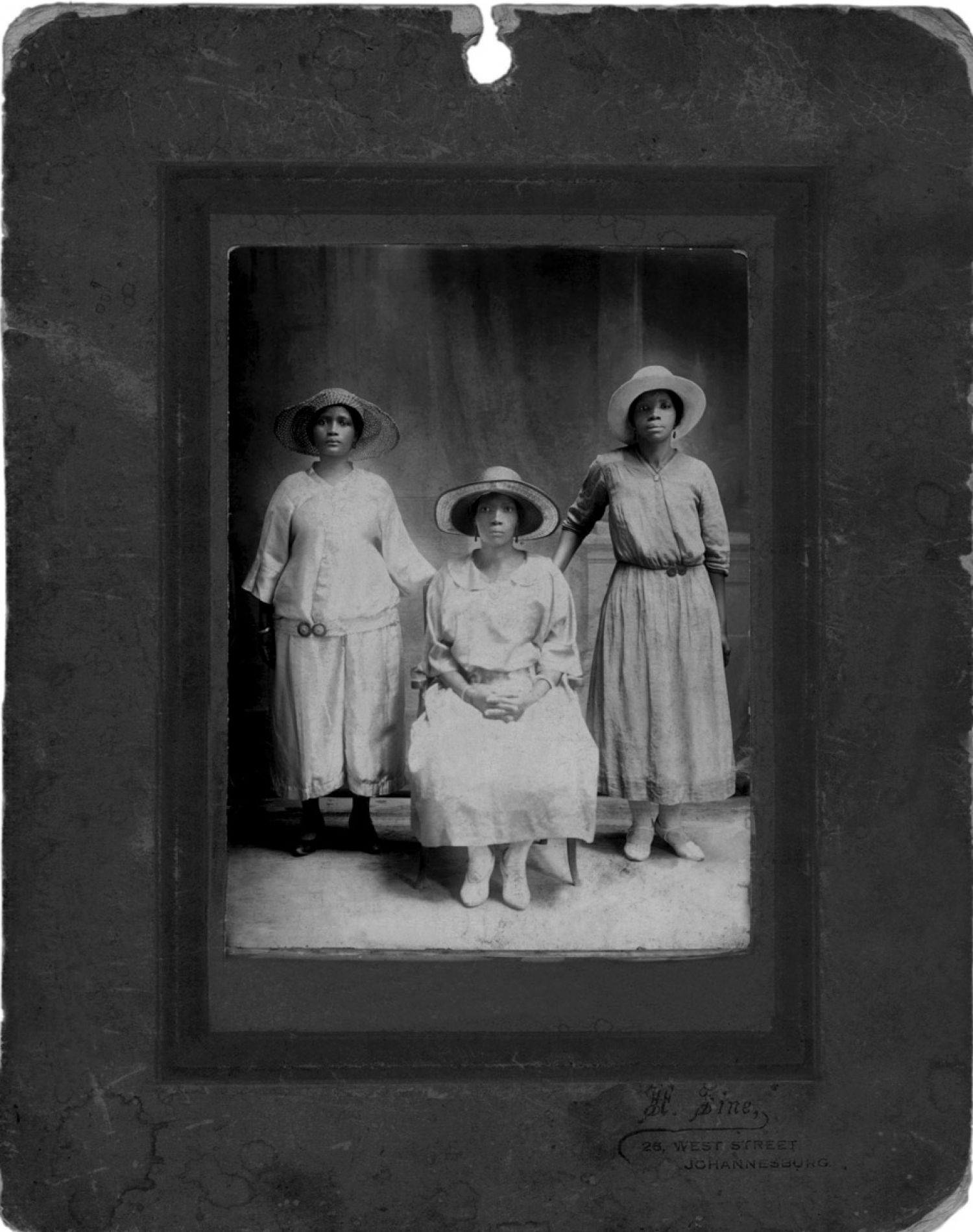

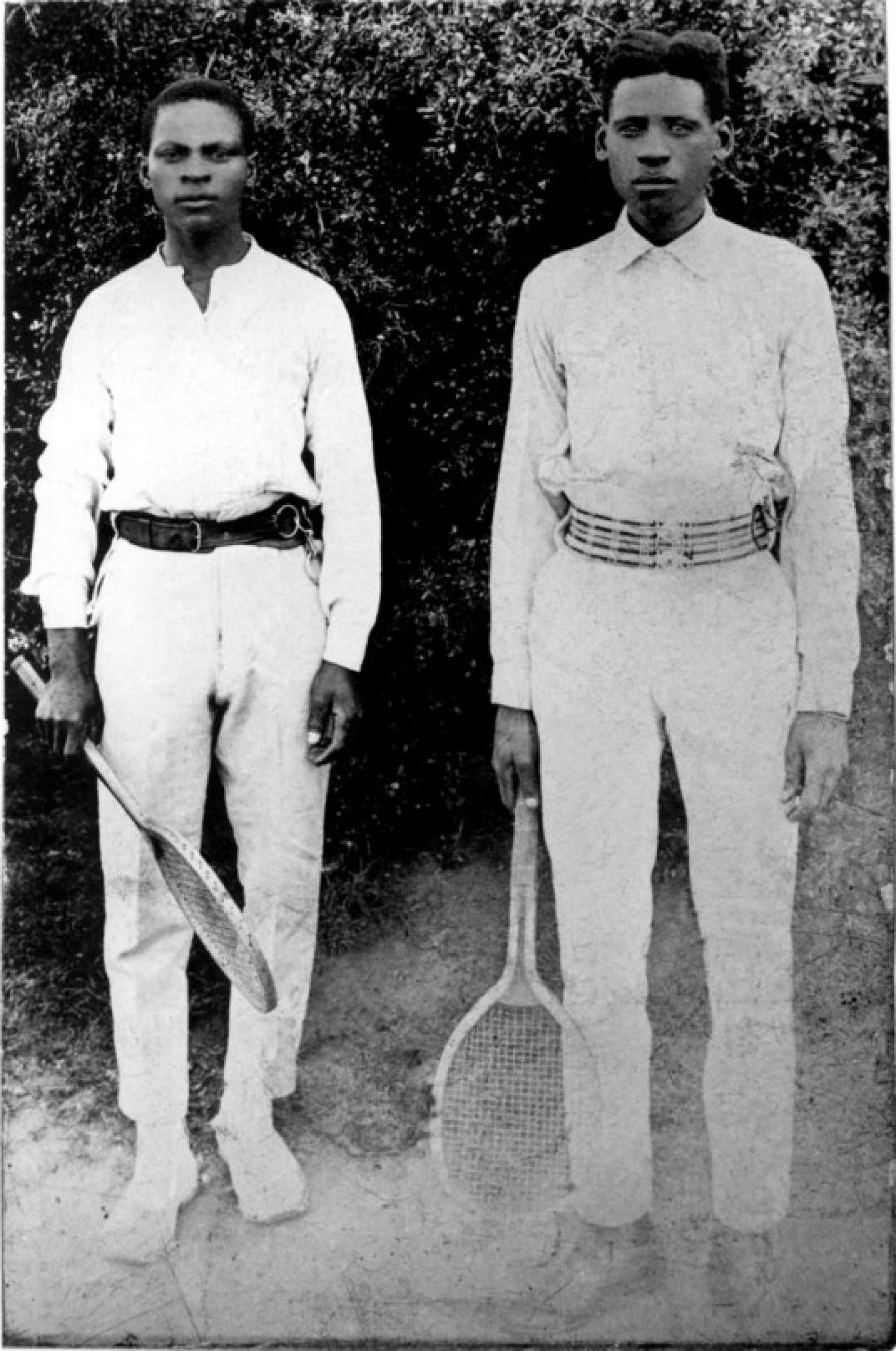

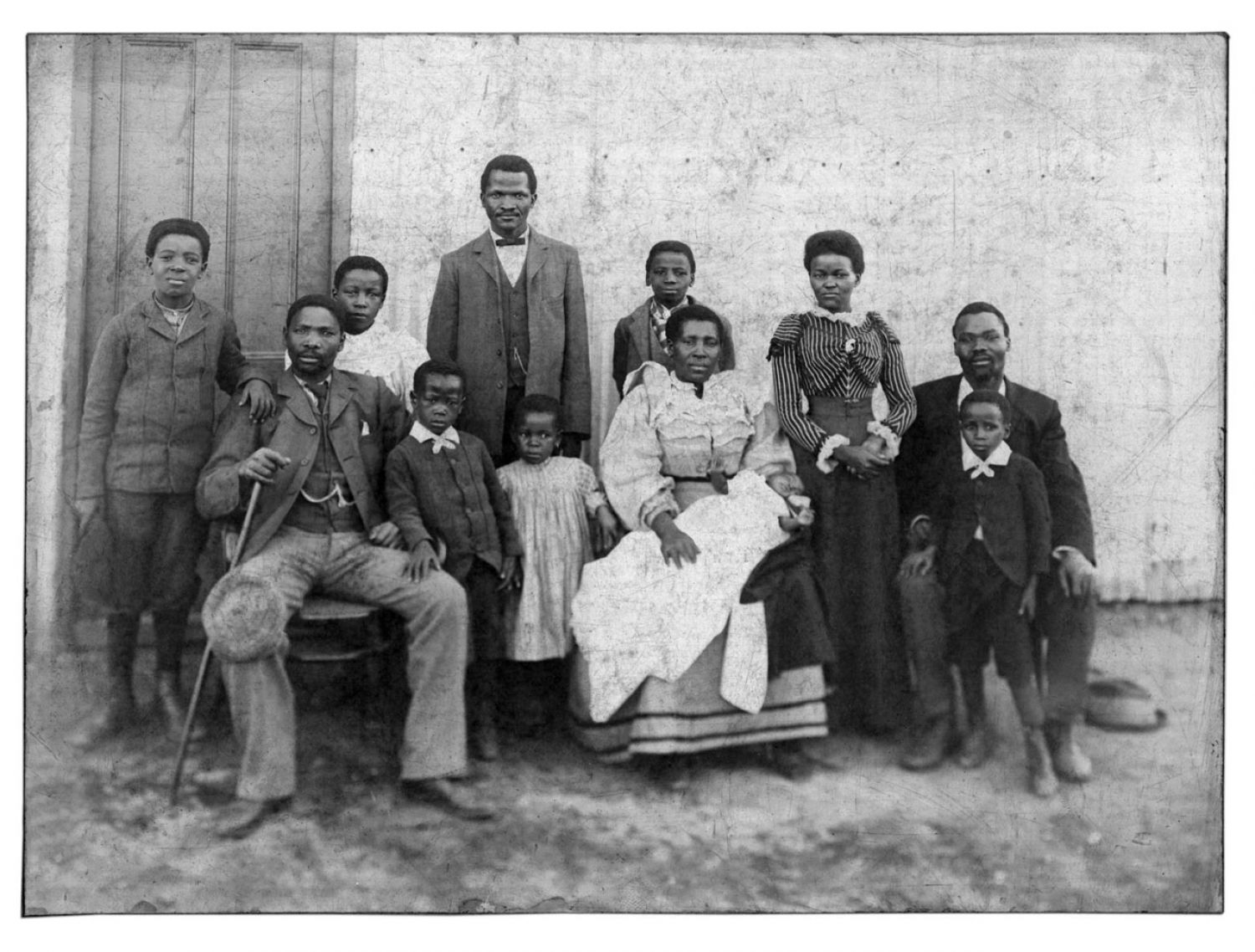

While a group of educated Africans, well integrated into the urban fabric, already portrayed themselves in Western features in the late 1800s, Western photographers were concerned with preserving the differences and «typical features» in the classification of tribes. On one hand, we have the work of the South African photographer Santu Mofokeng, a privileged witness to a forgotten story, who gathers in The Black Photo Album[7] a series of images taken between 1890 and 1950.

These photographs, found in old plastic trunks and envelopes, placed in closets or under the beds in the shacks of Johannesburg’s townships[8], were intended to be kept only in family archives and not to be seen for more than a century. On the other hand, we have the work of another photographer, Alfred Martin Duggan-Cronin, who in the 1920s began cataloguing work that would represent the face of South Africa in the eyes of the world.

The first images, mostly taken in the studio, are family albums, commissioned by those very people depicted. They are a testimony of the will of African élites to represent themselves in a Victorian style through a Western instrument. These images do not just replace the «typological» ones, but they are somehow an evolution of them: they derive from them and refer to them. They are the direct outcome of the need to distance themselves from the «other’s» look, after having realized the actual consciousness of this gaze; they are eventually the result of the quest for integration into foreign cultural codes, that somehow are a source of power and social well-being.

Conversely, the images of Duggan-Cronin reconstruct that idyllic imagery of traditional populations that aims to preserve the alleged authenticity of indigenous customs. Duggan-Cronin, born Irish and educated in England, photographed native workers employed in South African’s mines and their home villages and he produced a collection of images by the name: The Bantu Tribes of South Africa. Reproductions of Photographic Studies by A.M. Duggan-Cronin a publication of eleven volumes was published between 1928 and 1954. From a political point of view, they had a central role (given the visibility of the books and the acquisition of the archives by the Kimberley Museum) in defining the «representative features of the otherness.» They seemed to be the perfect justification for the racial policies of the South African nationalist party at a time when exalting diversity, rather than the points of contact, meant separating.

On an aesthetic level, however, the images are complementary, and both fall into the pictorialist movement of the early decades of the 20th Century, which turns them into aesthetic objects. The pictures look as if suspended in an almost unrealistic time, and this affects even the subjects of the images, who become prisoners of a static timelessness that sets them apart from the social, economic and political reality in which they are involved. In this sense we have an evolution in photography during the ’30, toward a more modernistic views as for example in the photography of Constance Stuart Larrabee and Leo Levson, that work more with subjects in context, but in any case the ethnographic approach is predominant.

2.

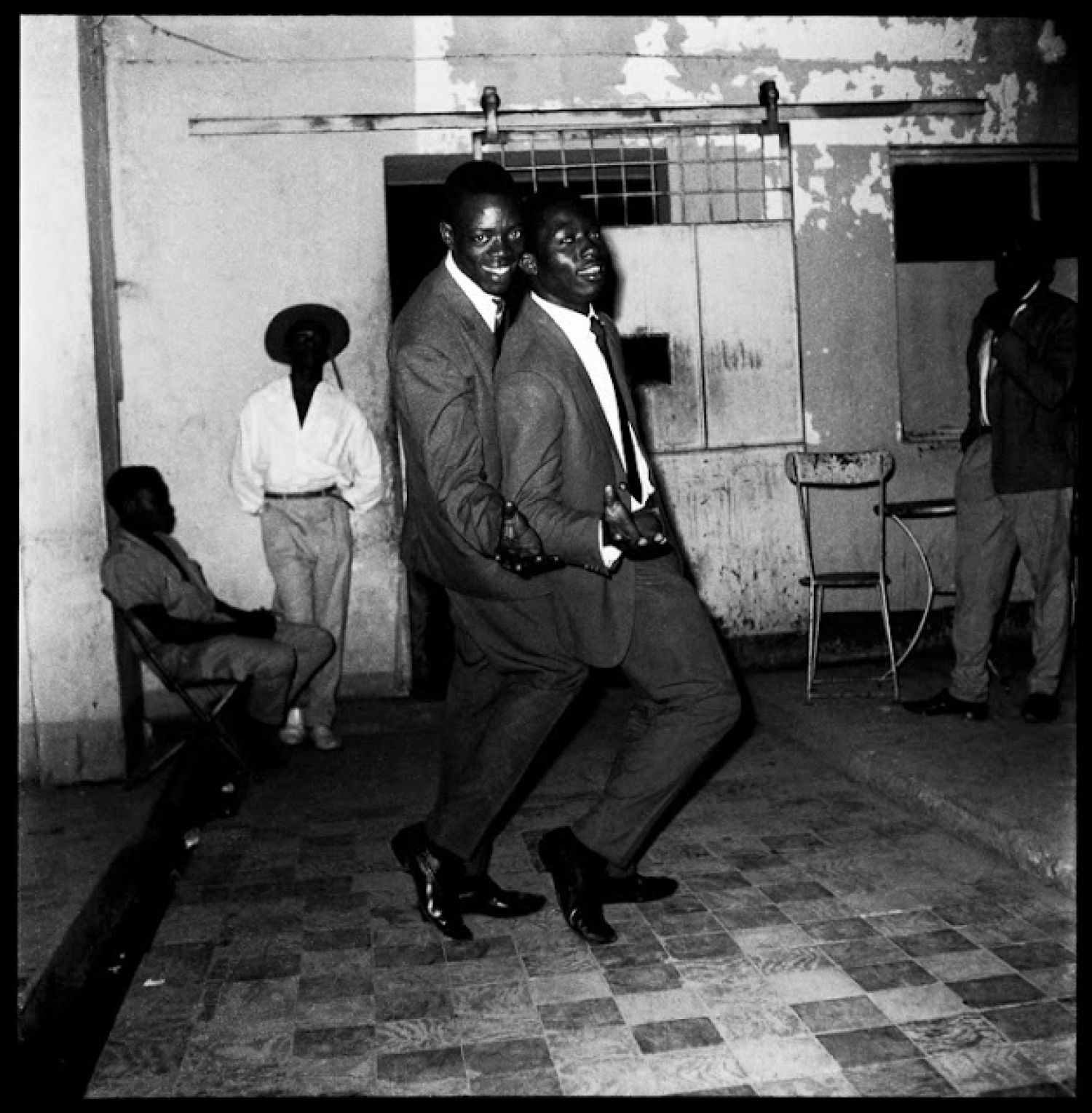

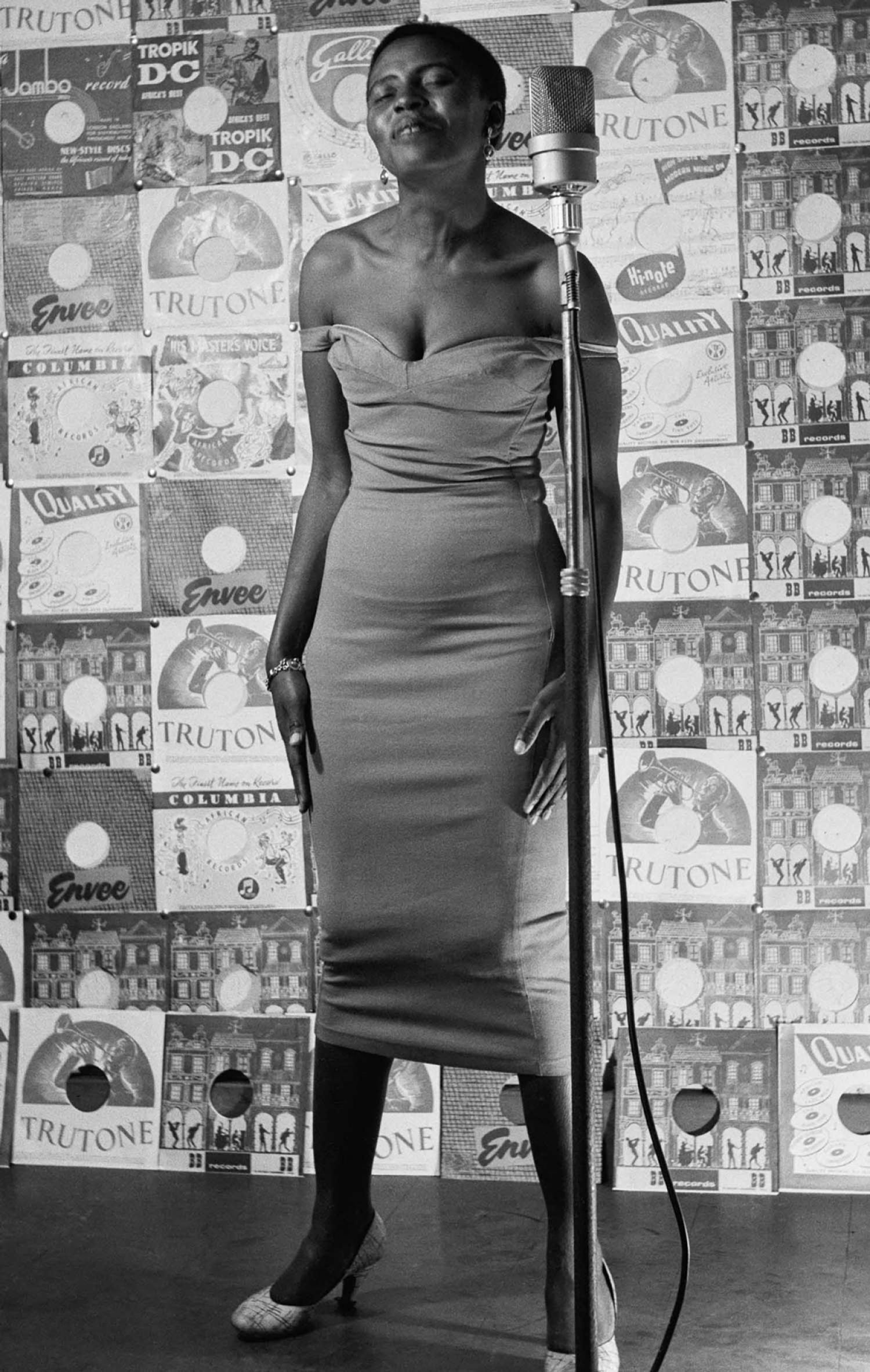

In Africa what we have described as «indigenous photography apprenticeship» and the awakening of an African social consciousness begins, as said, in the period between the two world wars. In the meantime, in the United States and in Europe, the modern illustrated press started to deal with photographs as an integral part of the narrative. The result was contemporary photojournalism and the opening of the first official photographic agencies. The images of that Western visual culture, made of pin-ups and famous characters, movie actors, jazz singers, glamorous dresses and sensual poses, begin to spread rapidly, creating a new imagery of reference.

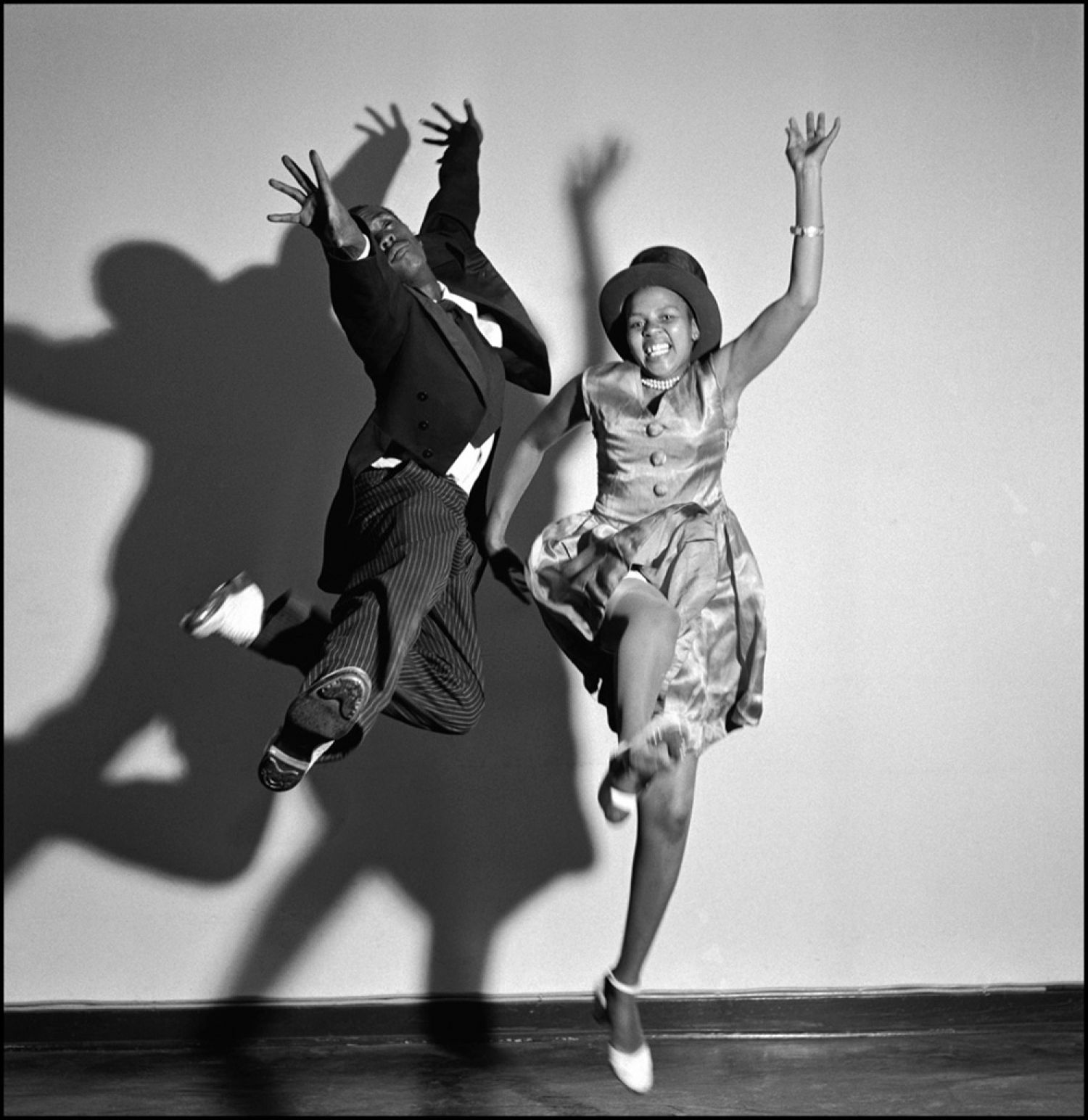

The Drum magazine, whose role was crucial in training South African photojournalists, was the one that best understood this global spirit and carried it into everyday reality. It played a key role in the development of the consciousness, mainly visual, of the life and culture of urban black communities during apartheid. Around this magazine an exciting mythology arose. Drum’s editorial board is indeed often depicted as a place where a talented generation of brave photographers and writers met progressive and enlightened publishers, joined in the passion for work; a place where effervescent and disinhibited creativity flourished as the product of a culture that expressed itself in the cracks of the apartheid regime. Actually Drum can be considered the mirror of that black renaissance, that sometimes frivolous optimism in the future, that distinguished the cultural climate of a crucial moment in the history of South Africa. But its history and heritage, in spite of so much apparent levity, remain controversial.

In 1948 winners of World War II signed the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the basis of the United Nations, and the starting point for many civilian achievements of the twentieth century. In South Africa this year corresponded to a stiffening of the segregationist regime in South Africa. Drum magazine was born in 1951 with the former name of The African Drum. The motivations that led an Afrikaaner journalist to found a newspaper for the black community could be view as philanthropic or paternalistic, but in purely economic terms, investing in this new audience, was a convenient bargain for anyone who was not closely linked to racist ideology.

The substantial innovation of the magazine was in the fusion of traditional storytelling that came from the oral tradition, with the new tools and technologies of the international press. The extensive use of images, complementary to texts, was more suitable for a modern audience (the black urban community), and showed them a whole new repertoire of knowledge that would allow the new urban generations to bridge the identity gap with their home villages. Nevertheless, after a few issues, structured in a highly academic and ethnographic way, the newspaper began to be modelled on American illustrated magazines, such as Life and Picture Post.

The layout was revolutionary, The African Drum changed its name to Drum, and the editorial team gathered collaborators of different backgrounds. In a country that did not hire black journalists, a newspaper gave them space and voices. The insights on tradition-related topics were soon replaced by chronicle and costume stories, criminals and gangsters: the new urban life in all its restlessness and vitality.

By the mid-1950s the photographic styles used in the magazine were a somewhat eclectic mix, where the studio portraits, photo-narratives coexisted with the social documentary, but the latter soon prevailed, focusing more and more on an essential aesthetics.

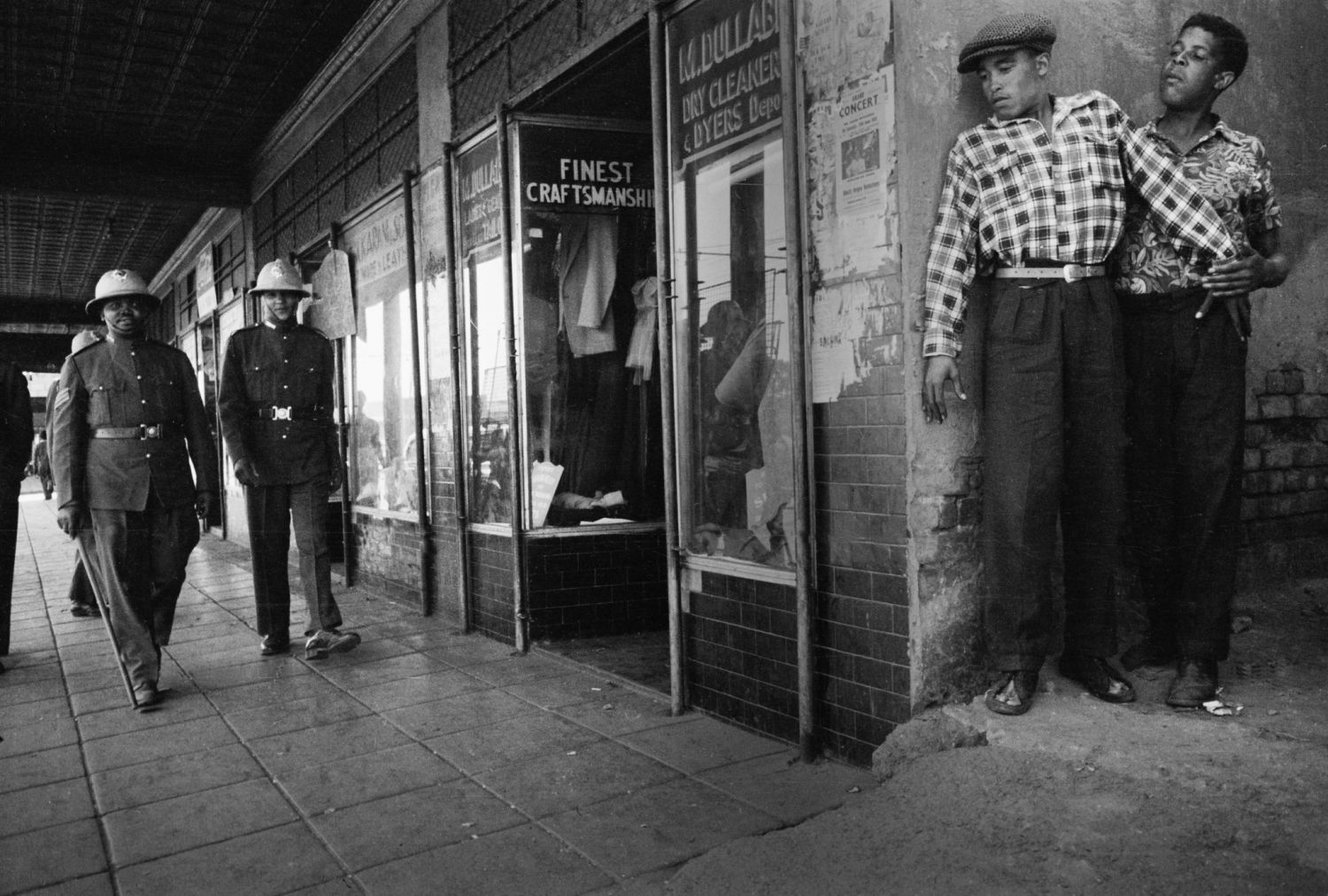

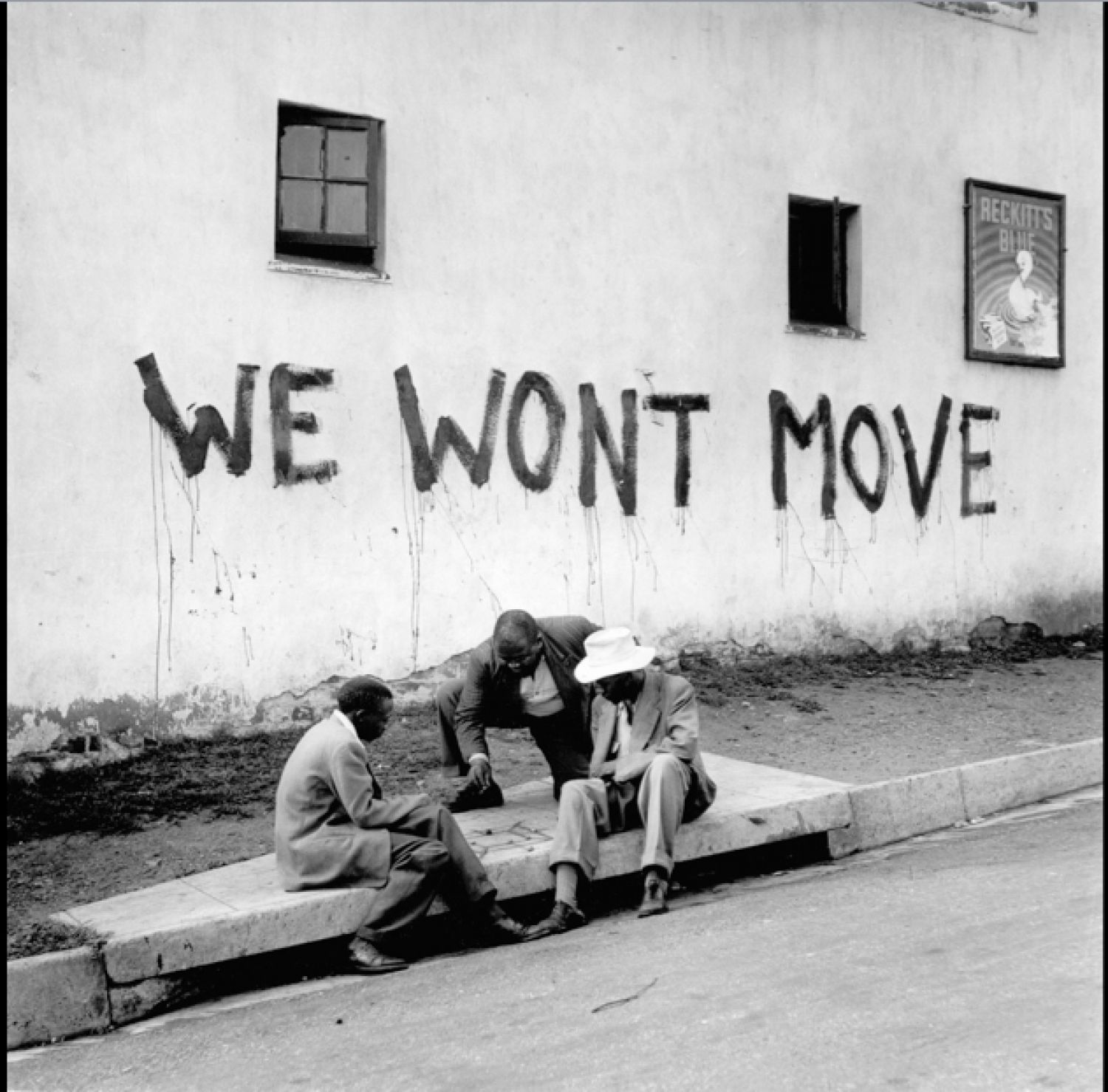

Drum's real breakthrough was in this sense the exposée stories, visual reportages that brought to light everyday stories of injustice, from that petty apartheid that had a profound effect on social psychology, to the reports on the exploitation and mistreatment of black workers, or the forced evictions and deportations into the townships.

This type of work made Drum’s photographers increasingly brave and skilled in catching images of extreme and dangerous situations. It also helped them in some way to create that distance from the reality in which they were involved.

As Newbury writes, Drum was born and shaped in the crossroad of two forces: the resistance to racial laws animated by a progressive spirit of optimism in the future, and an apartheid machine increasingly repressive. In this climate, the approach of the magazine was an immediate need to be «here and now», to record what was happening in all its gravity and intensity. For this task photography was undoubtedly the most appropriate instrument. The magazine, in its apparent levity and irony, generated a profound seriousness of vision and orientation, becoming an eye on that world that many refused to look at.

By the end of the 1950s, much of the newspaper's most frivolous content disappeared, and photographic equipment was replaced with new and better tools. The Leica soon replaced the medium format, and the magazine began to be printed on a different paper that would enhance the images. Drum photographers remarkably improved their technique and learned to build coherent reportage from a stylistic point of view. They participated and won international competitions, and the world started to look at them. Photographers such as Peter Magubane, Ian Berry, Ernest Cole, Bob Gosani, Alf Kumalo, Eli Weinberg, the first generation of South African photojournalists, owe so much of their ability and expressive capacity to their apprenticeship at Drum, which had an intense but very short life. The magazine ceased publishing in the early 1960s, under the pressure of incessant restrictions and ever-heavier threats by the government. Levity, frivolity, and hope in shared progress were no longer part of Africans' daily lives; Mandela was already in jail with many of the members of the ANC; the party was now illegal, and the resistance began a stage of violent clashes.

Two moments were fundamental to this brutal change of course, both photographic and socio-political, and both, in their own way, contributed to creating a different awareness of the social role of African photographers.

3.

In the case of South Africa, there is a term that characterizes protest movements and the dissatisfaction of dissidents, and it is «resilience». While «resistance» means «to stand or hold out against an opposing force», «resilience» refers to «the ability of materials to withstand shocks without breaking,» adapting itself and self-repairing.

This idea of flexibility, which enables one to re-establish the self after every hard blow and to keep on the struggle with even more conviction, is perhaps the closest image of the strategy of South Africans against the apartheid regime. Such a commitment aims to show those symbols that ritualize the strict spatial and social code of apartheid in everyday life, a challenging task to sustain visually. This presupposes, in fact, a degree of awareness and detachment from the usual, and from the habits, which allows the photographer to show the boundaries between law, norm, and life.

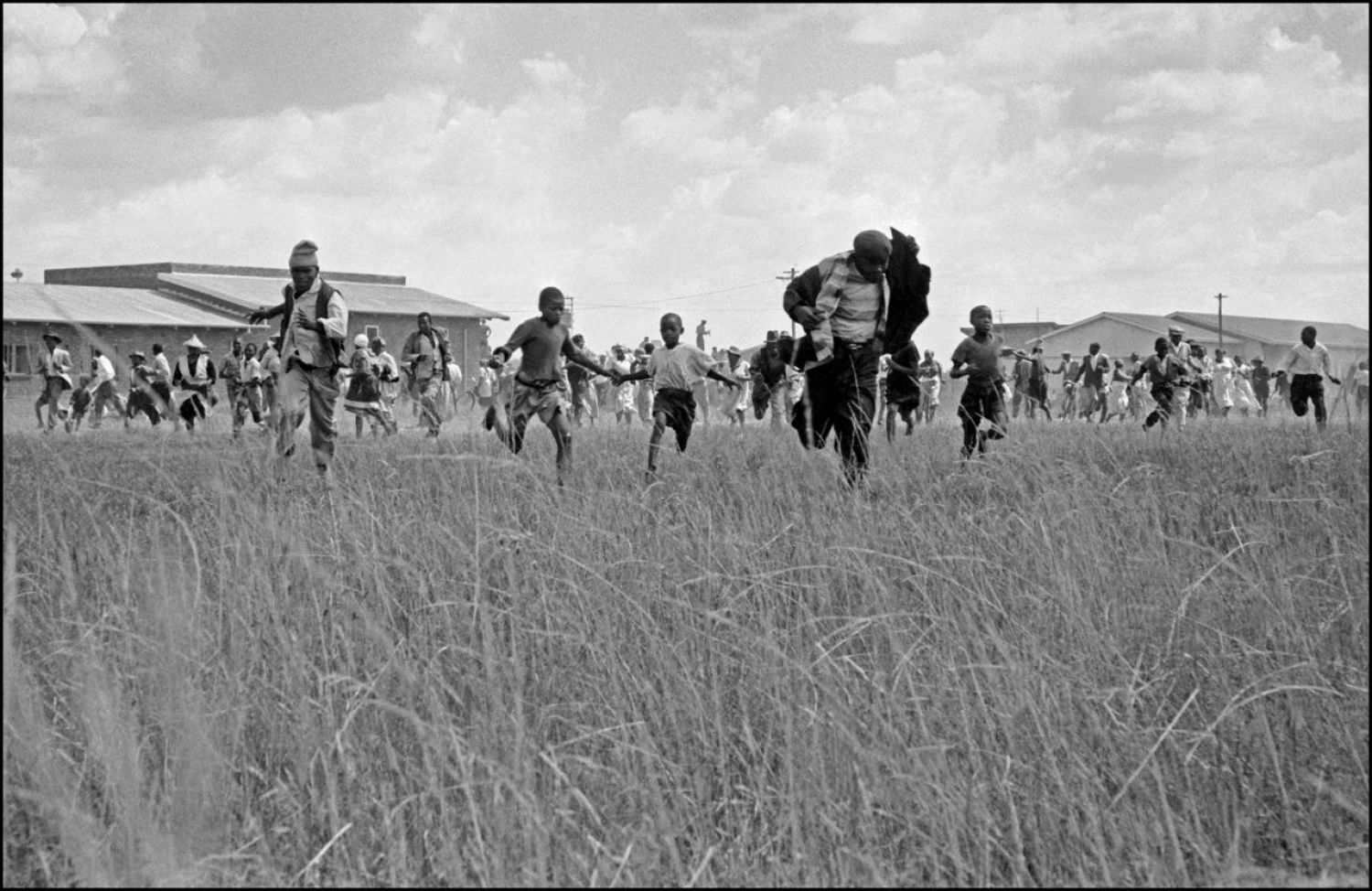

On 21 March 1960 the PAC[9] launched a peaceful campaign across the country against the Urban Area Act: law that required non-white South African citizens to always carry a special pass (a booklet containing all the data related to the owner). This pass was supposed to regulate the access to white areas and prevented non-whites from freely moving within the cities. Members were called upon to leave their passes at home and present themselves for arrest. People responded in large numbers particularly in Sharpeville, where more than five thousand demonstrators gathered at the police station, declaring themselves without a pass. The police opened fire on the unarmed crowd killing 69 people (including women and children) and injuring 180 others. The sequences of the massacre, in the snapshots made by the two Drum’s photographers, Peter Magubane and Ian Berry, are now carved in the collective memory and represent a significant lesson of photojournalism.

That event with the related circumstances, suddenly imposed the attention on the importance of being «there», present and awake, courageous and merciless, to convey a testimony to the world. Ian Berry, who did not see his service published until October, due to the direct censorship of all government-issued publications, gave birth that same day to a practice that would have a long track record throughout all the remaining apartheid years. Indeed he sent his shots directly to Europe, at the London Press Room, to be distributed to the world press, thereby bypassing the South Africans local media.

Sharpeville's massacre also marked a radical turning point in the opposition to apartheid, which from the traditional nonviolent protest following the example of Mahatma Gandhi's philosophy, turned to a stage of urban guerrilla warfare and armed struggle. Consequently, there was a remarkable evolution in the photographic style of the South African reporters, who were no longer related to any magazine and started to work with the world agencies and the foreign press.

The Sixties in South Africa were years of repression in which the state of emergency became normal and all the associations, trade unions and political parties opposed to the regime were declared outlaws. Ten leaders of the ANC, including Mandela, Tambo, and Sisulu, were sentenced to life in prison. An overwhelming censorship made the passage of information nearly impossible, and many photographers, after repeated threats, arrests, abuses, and tortures, were forced into hiding or exile.

After 1960 the clenched fist became a gesture of iconic reference, as any chance or hope in peaceful negotiation faded. The same clenched fist that spread across the rest of the world as an international symbol of black power, as a sign of resistance, of opposition against oppression with every possible means. It is important to emphasize the iconographic potential of such a gesture in photographs, where the signifier becomes significance, and propagates beyond geographic and temporal boundaries as a symbol of self-affirmation. In the context of the struggle against apartheid, signs, and gestures shown in marches, or during strikes and funerals, became a discursive framework, fundamental forms of non-verbal communication. They become a new language, a pervasive, unstoppable, universal code.

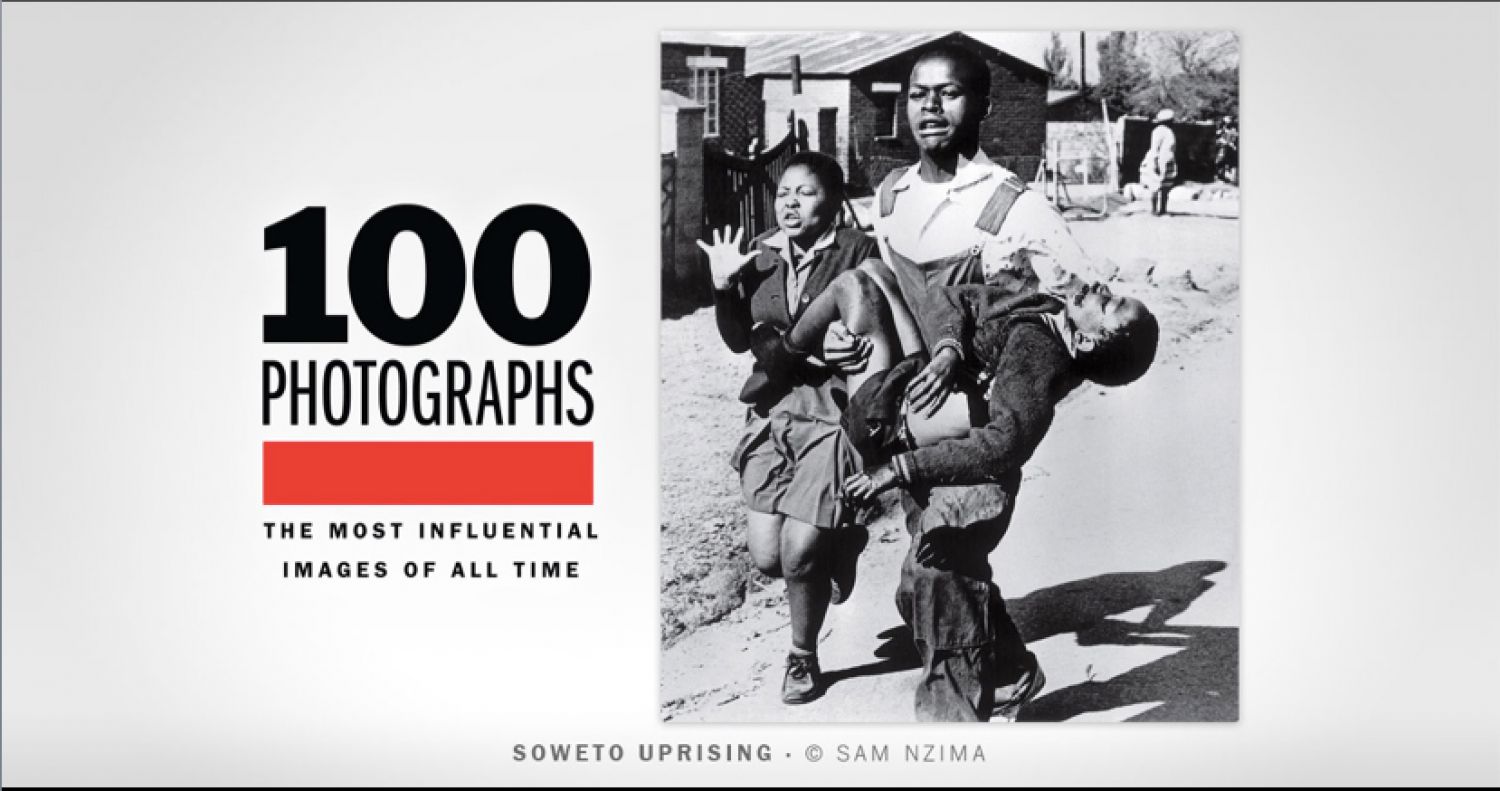

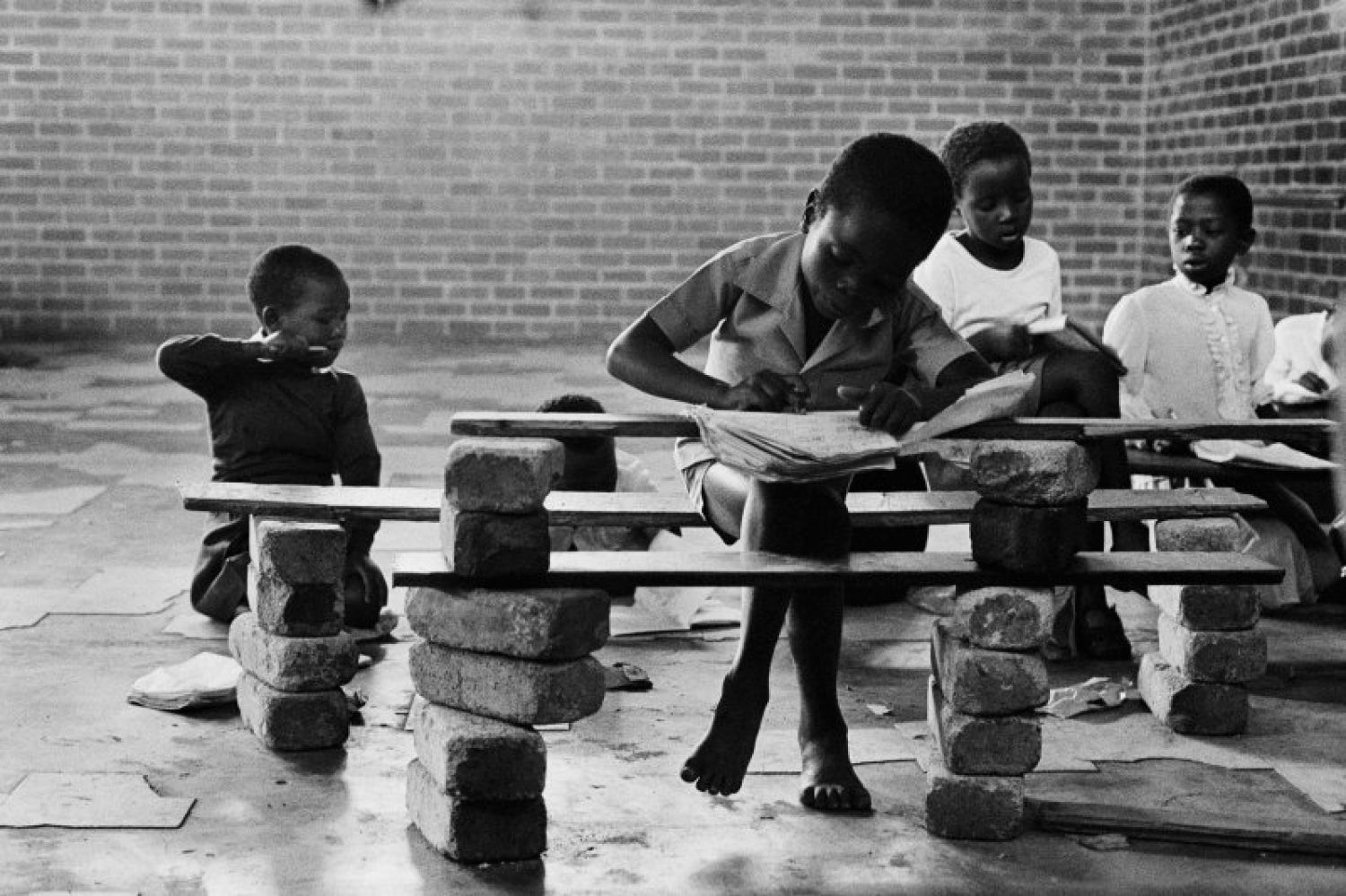

In 1976 a new massive uprisal, followed by increasingly brutal attacks, was triggered in the townships and another tragic event strengthened the rage of the movement and its supporters. The reason for the clash this time was a government decree, requiring all schools for blacks to use Afrikaans alongside English as a medium of instruction. This order came after several measures[10] were conceived to neglect black education, to ‘train and fit’ Africans for their complementary role in the apartheid society.

This time in Soweto, during a peaceful protest of young students, police officers shot randomly at the demonstrators, all students, mostly underage. Even in this case, as in many others sadly famous in history, a photograph became the icon of a tragedy, contributing in some way to that new documentary impulse that established a foothold in the world of international photojournalism.

After Soweto, neutrality was no longer sustainable, war became open, and social criticism was getting more and more aggressive. The armed struggle would decimate what has been termed the «lost generation»[11], while intellectuals and artists of each colour started to mobilize in a unified front opposed to the regime.

In the history of «official» photography, the term «concerned photography» is commonly used to define the work of those photographers who use their images, sometimes violent and dramatic, not just as a testimony but with an educational purpose. In the history of South Africa, where concerned photography becomes the norm, a new term was coined to define the mainstream photography over two decades of struggle, and it is «struggle photography». In fact, although most of the photography produced since the 1950s denounced the regime, the real militant, engaged involvement, was in direct response to the events of Soweto.

Collective action started to fill the cultural gap, thereby establishing a comprehensive network of clandestine schools (with a whole range of mutual assistance services such as free healthcare, consultancy and economic support for the families of political prisoners and victims). Their primary purpose was to educate a population of fighters, to awaken their consciences and to provide them with the theoretical and technical tools of emancipation from physical and psychological oppression. At the same time, the direct contact with the population allowed people to fill gaps in visual vocabulary and build a shared context of reference.

Cooperation, engagement, and involvement became keywords in the daily struggle. Even the status of «artist» was replaced by the new figure of the cultural worker bound by social responsibility. The camera, the pen, the notebook, the musical instruments, all became weapons of war. The importance of photography became capital, and functional to the struggle itself, and for many young photographers, this represented not only the focus of their work but the very structure and framework that made their work possible.

At the end of the Seventies many self-published publications and reviews were born.

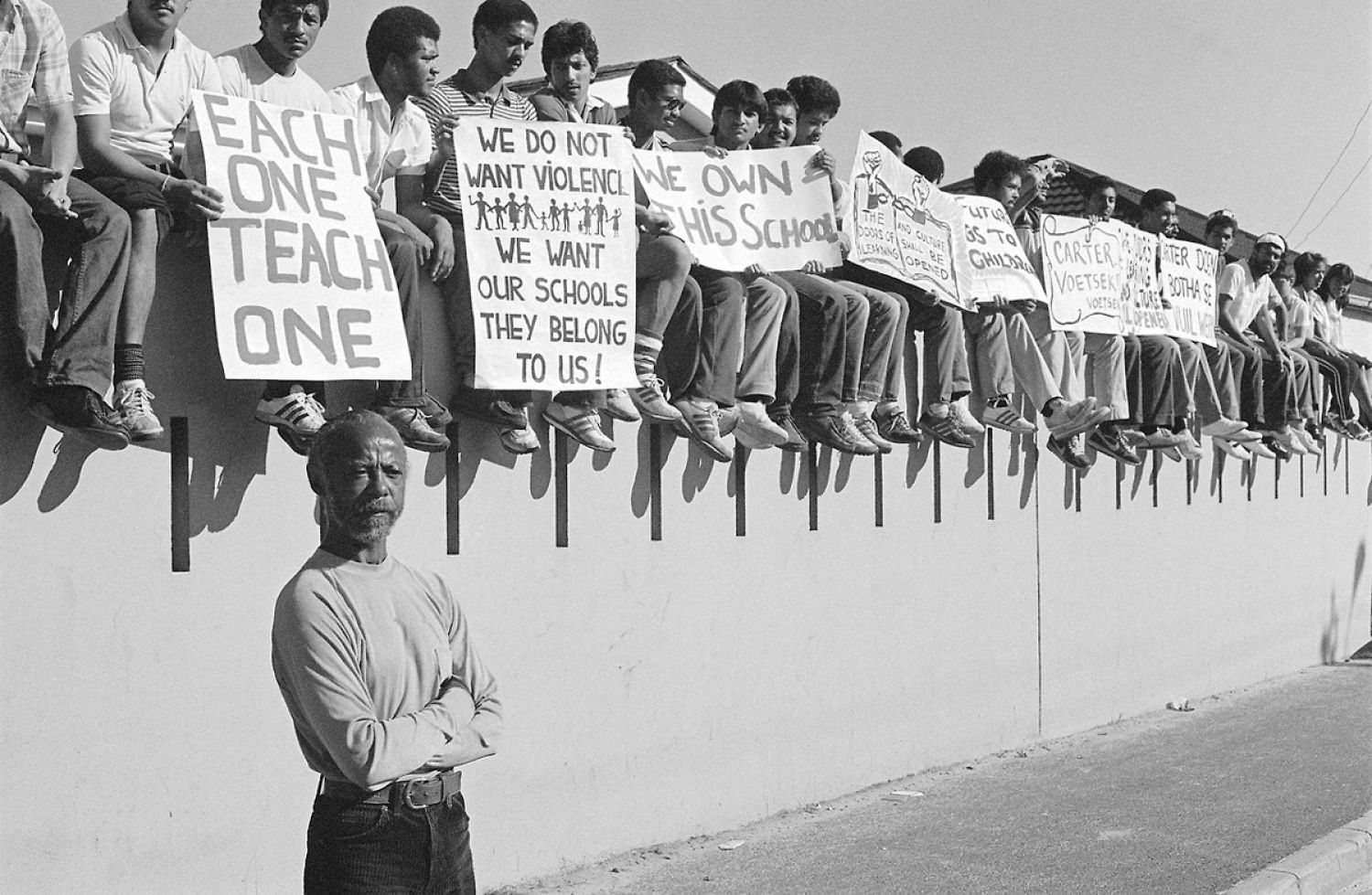

Amongst them, notably was Staffrider[12], a significant literary and cultural magazine which enabled the expression of culture, history, and protest in the form of poetry, short stories, graphic art and photography from southern Africa. Thanks to the annual exhibitions organized by the newspaper's editorial staff, young militant photographers found a privileged space to show their work. Against the state propaganda, photographers and united intellectuals, reacted with a «morally fair propaganda», showing what the country could not or did not want to see[13]. In an article titled «Bringing the Struggle Into Focus» and published in Staffrider in 1982, Peter McKenzie set the standards of struggle photography as a weapon of communication in the fight, by appealing to the «undeniable responsibility of all South African photographers, to use every means to establish a democratic government»[14]. McKenzie writes:

«Communication depends on the assumption that photographer and viewer share a common culture. […] [the documentation] shows the effects of injustice. They show the shocking conditions that people are forced to cope with. […] These images are meant to awaken the sleeping consciences of those who haven’t yet realized their oppression and the danger of non-commitment to change. […]We’ve got to show the hope and determination of all committed to freedom. The photographer must serve the need of the struggle. He must share the day to day experiences of the people to communicate truthfully. We must identify with our subjects in order for our viewer to identify with them […] We as photographers must also be questioning, socially conscious and more aware than our predecessors»[15].

Peter McKenzie is also among the founders of Afrapix, the most important of the various collectives of photographers born in the early 1980s. Established in Johannesburg, but with separate offices in Cape Town and Durban, this organization counted, in its almost ten years of activity, with more than forty members including some of the most prominent South African contemporary photographers.

Afrapix's primary purpose was to document the country and what was happening there, as well as to expose the images as much as possible in different contexts, Thereby contributing to their diffusion. On one hand, members engaged in the organization of many workshops and practical classes across the country to train new photographers and to contribute to the visual education of the South African black population. «Each one, teach one,» became the slogan and the essence of the collectivist spirit and the very basis of Afrapix's history. On another front, Afrapix worked to provide images to several international organizations, newspapers, photographic agencies, support associations against apartheid and trade unions, to denounce the state of emergency and spread the spirit of resistance.

At a certain point, this meant to meet the increasingly pressing demands, especially in Western Europe, for iconic images, dense with «blood and violence» following a trend more and more practiced in international photojournalism. A sort of cliché arose around South African photographic production after the 1980s, and quite strong criticism of it continued through into the post-apartheid. For some, the social documentary mode adopted by South African photographers subordinated the image to the propagandistic needs of the moment, codifying a one-dimensional image of the black life, an idea of black people eternal victims, reducing the complexities of inner experience.[16]

The camera became for many, almost confirming McLuhan's thesis, an extension of the natural sensibility, and at the same time a screen, a shield that filtered the experience. Most of the images produced and shared by the collective are thus characterized by a lack of attention to aesthetics in favour of immediacy and representativeness. The slight care reserved for photographic quality was sometimes accompanied by the total lack of authorship. Works were often published in corporate collections, and even for security reasons, photographers’ names were not reported.

It should be noted, however, that these images were mostly intended for the liberal and international press, and to supply overseas markets, so this «fungible stereotype» was also the one that has been circulating more widely and for longer. A more in-depth analysis, reveals instead that Afrapix promoted a much more comprehensive range of photographic idioms, and images that reflected the complex emotions of the people portrayed, their humanity and the dignity of everyday life in urban black communities. With these images they aim to suggest that the struggle within and the struggle without were one and the same.

4.

In the international trend, thanks to US politics, never too approving of engagée artists, newshound reporters began to develop an aesthetic of the horror. That kind of images that, according to Susan Sontag, serve to convey a double message:

«They show a suffering that is outrageous, unjust, and should be repaired. They confirm that this is the sort of thing which happens in that place. The ubiquity of those photographs, and those horrors, cannot help but nourish belief in the inevitability of tragedy in the benighted or backward—that is, poor—parts of the world […]This journalistic custom inherits the centuries-old practice of exhibiting exotic— that is, colonized—human beings […] For the other, even when not an enemy, is regarded only as someone to be seen, not someone (like us) who also sees».[17]

After the release of Mandela from prison in 1990 and during the process of transition to democracy, the danger of a civil war became more and more tangible. Many photographers sent by the foreign press corps flocked to cover the breaking news. A new level of photojournalism led to the birth of an increasing number of newshound reporters, including the so-called Bang Bang Club (Kevin Carter, Greg Marinovich, Ken Oosterbroek, and João Silva), formed by four young men, two of whom won with their work the Pulitzer Prize. Many photographers of Afrapix distanced themselves from the spiral of mere representation of violence and from what, once again, seemed to be a new but ancient stereotype. They started questioning their work and their role as witnesses and asked themselves how the original intent and significance of their work could appear so changed.

Their different and heterogeneous backgrounds and projects constituted in this process both a strength and a significant weakness of the collective. Afrapix ended its history in 1991, and many of its members oriented turned to personal projects or collaborations with professional photographic agencies; others continued their training. In the void left by the sudden lack of daily involvement, what for years had been the vital engine of every decision and commitment, emerged countless possibilities of explorations.

In the post-apartheid, physical and mental displacement, uproting and disorientation were all traumas to solve that photographers sought to investigate to than better understand. The definition of the self, of memory, dreamed or real, thus became a constituent element of a schizophrenia that makes people feel involved and strangers at the same time.

Henri Cartier-Bresson said, «It is living that we discover ourselves, at the same time we discover the world around us, it shapes us, but we can also act upon it [...] through our lens we accept life in all its complexity». Maybe the only possible meaning of life emerge in the ongoing relationship between man and the world, an achievement that seems to mark the story of African photographers, especially those South Africans, according to the recent lines of research on photography.

A long iconographic tradition throughout the whole history of Western art, provides us with a certain familiarity with a shared visual language. In this sense the icons of the struggle are recognizable among those gestures that Warburg defines as Pathosformeln (i.e., crystallizations of historical memory). On the contrary there is no real vocabulary for the invisible of apartheid. «Violence is in the knowledge»[18] says Santu Mofokeng, generation of '56, Afrapix militant from 1985 to its end, had been a key figure in the critique of documentary photography during those years. The violence is indeed not directly in seeing, it refers to a visual and cultural code shared in a given context. Making that reference code explicit and explaining it to others is a challenging task for those photographers whose research goes in that direction, because as Henri Bergson writes, «The eye sees only what the mind is prepared to understand». Then the experience of contact with the new, the unexpected and the different is subject to a process of systematic correction of the physical (ocular) perception by the moral perception (ideological and cultural); each one thus only recognizes what he knows, what he can or wants to see.

The same images of The Black Photo Album, hidden away as they were acquire a different value if considered in the context from which they came. They are not merely studio portraits of a mixed-racial bourgeoisie born from colonial commerce, but a significant testimony in the context of apartheid. Mofokeng's work, by mapping the imagery of black life before apartheid, focuses on the creation of a new visual imagery that could break down stereotypes, and thereby recreate a context of reference; a corpus of work that would help remind, revalue and reflect the forgotten history of those black subjects. This type of work, like that of many other photographers of the same generation, lay the foundation for imagining a new South Africa. Looking for the underlying structures of everyday life, they tried to create that once unknown visual vocabulary, by photographing the absent, by looking for what is missing, thus guiding the gaze into a future transformation.

In the new Scramble for Africa by the world of contemporary art and the assault on the archives in search of the essence of African photography, a work of this depth reflects on how many possible ways exist, existed and still wait to be explored, to transform photography into a weapon for social change. But it also raises questions on the implications and the risks of this weapon turning into a double-edged sword.

Bibliography

BENEDUCE R. (2010). Corpi e saperi indocili. Guarigione, stregoneria e potere in Camerun. Torino: Bollati Boringhieri.

HEIDEGGER M. (1977). Letter on Humanism, in Basic Writings. London: Routledge.

HAYES P. (2009). «Santu Mofokeng photographs. The violence is in the knowing», in History and Theory 48(4).

HAYES P. (2017). Photographic Publics and Photographic Desires in 1980s South Africa, photographies, 10:3

HAYES P., «Power, Secrecy, Proximity: A Short History of South African Photography», in Kronos, n. 33 (November 2007), University of Western Cape.

MCKENZIE P. (1982). «Bringing the Struggle Into Focus», in Staffrider, vol. 5, n. 2.

MCLUHAN M. (1994). Understanding Media. The Extensions of Men. The MIT Press.

MOFOKENG S., CAMPBELL J.T. (2013). The Black Photo Album / Look at Me: 1890-1950. Gottingen: Steidl.

NEWBURY D. (2009). Defiant Images: Photography and Apartheid South Africa. Pretoria: University of South Africa Press.

OGUIBE O. (2001). «The Photographic Experience: Toward an Understanding of Photography in Africa», in Flash Afrique: Fotografie aus Westafrika. Gottingen: Steidl Verlag

SANNER P.A. (1999). Comrades and Cameras in Anthologie de la photographie Africaine et de l’Océan Indien. Paris: Editions Revue Noire.

SONTAG, Susan. (2003). Regarding the pain of others. New York: Picador.

SONTAG,Susan. (1979) On Photography. London: Penguin Books.

SOSKE, J. (2012 ). (n.d.) In Defence of Social Documentary, Retrieved March 25, from SA History website

WERNER, F. (1993) «La photographie de famille en Afrique de l’Ouest. Una méthode d’approche Ethnographique» in Xoana. Images et sciences sociales, n. 1.

ZAMPONI, M. (2009). Breve storia del Sudafrica. Dalla segregazione alla democrazia. Roma: Carocci.

Footnotes