r

e

v

e

s

Brazilian photographers Nair Benedicto (1940) and Rosa Gauditano (1955) started their professional lives during the military-civilian dictatorship that governed Brazil from 1964 to 1985. They belonged to a generation of young photographers who lived and worked through the social and political changes that happened at the final part of the authoritarian regime, and both were able to find in documental and journalistic photography a possibility of personal expression as well as political engagement.

They were also part of an important period of the history of Brazilian photography when institutionalization of artistic and documentary photography and professionalization of photojournalism occurred. Both photographers were engaged in the fight for a unified sale price list, for image rights and for freedom for pursuing their own news stories during late 1970s and early 1980s.

Working for the alternative press, Benedicto and Gauditano were able to document in photography that specific political culture.

One of the most relevant stories they worked on that period, which is closely related to their left-wing political engagement and have an important place within the body of their work, is the series of strikes that happened in industrial areas (ABC) in the outskirts of São Paulo from 1978 to 1981.

Photography and the strikes in São Paulo’s ABC

The military coup that deposed Brazil’s legitimately elected president happened in 1964. Four years later, in 1968, the military government instituted the Ato Institucional número 5 [Institutional Act number 5], or AI-5, intensifying the repression mechanisms against their opponents. While the world experienced the political, cultural and behavioural changes boosted by the happenings reverberated from Parisian May 1968, in Brazil these transformations were violently repressed and suffocated.

However, around 1974, several internal and external factors lead the country’s economy as well as other regime basis to go into crisis, making the government lose some of its support. General Ernesto Geisel, president at the time, then elaborated the plan of a slow and controlled political opening. According to Bernardo Kucinsky, it was «A gradual and controlled way out of the authoritarian regime that would demand in medium term the breach of the opposition monopoly by the MDB[1], and therefore relaxation on political activities control, left opposition decriminalization, end of previous censorship. In the long term, substitution of physical coercion, efficient only when combating small groups, by ideological domination, necessary when controlling mass opposition»[2]. Despite still using a strong repression against opponents, this political opening allowed that certain initiatives and repressed desires, kept clandestine until then, to finally emerge.

The strike wave in industrial districts close to São Paulo city (known as São Paulo’s ABC, comprising the peripheral cities of Santo André, São Bernardo do Campo and São Caetano) started in the Saab Scania factory on May 12, 1978, spreading to more than ninety factories in less than ten days, most of which being car manufacturers. In the following year new strikes would show a better worker organization, gathering more than one hundred thousand workers. These strikes, which would continue to challenge government and employers until 1981, have a fundamental political meaning in this period, removing from the hands of the authoritarian regime the total control of the political opening process recently set in motion. These events also put in evidence a new social subject who until then did not have representation space in the hegemonic media, nor in the discourse of the Brazilian traditional left – the worker.

Acting on their own, far from the editorial guidelines of the mainstream press – which adopted editorial guidelines ranging from self-censorship to a discourse of open support to the regime – Nair Benedicto and Rosa Gauditano photographed, as freelancers, the main events of the 1978-81 intense worker mobilizations.

They documented the workers routine in the labour unions, for instance the various conferences during which they discussed negotiations, employer proposals and the end of the strikes. Between 1979 and 1980, those general conferences usually took place at the Vila Euclides sports stadium in São Bernardo do Campo. The photograph Rosa Gauditano took in 1980, reproduced on Image 1, shows one of these assemblies. Among the crowd occupying the stadium the newspaper Em Tempo stands out lifted by one of the voters. Em Tempo was one of the many left-wing publications that became known as the «alternative press», a counter part to the hegemonic press and opposed the regime. It was also one of the newspapers to which Gauditano sold her photographs.

According to Gauditano her work process was quite autonomous. She made her own guidelines. When she knew there would be some important event she would attend it on her own, photograph it without any editorial imposition. She developed and enlarged the photographs at home, edited them, and afterwards offered them to alternative newspapers such as Versus and Movimento, besides Em Tempo[3]. ABC strikes were some of the first stories she made while starting her career as photographer. Nair Benedicto, on the other hand, already had an established career at that time. Since 1972, when she graduated from university, she worked as a photographer, founding the cooperative agency F4 with three other photographers in 1979. One of this agency’s main goals was to provide the photographers an autonomous work process. Gauditano and Benedicto’s work processes to make their photographic stories were similar in this sense, prioritizing the independent visual interpretation of events, therefore imprinting to the images their political views.

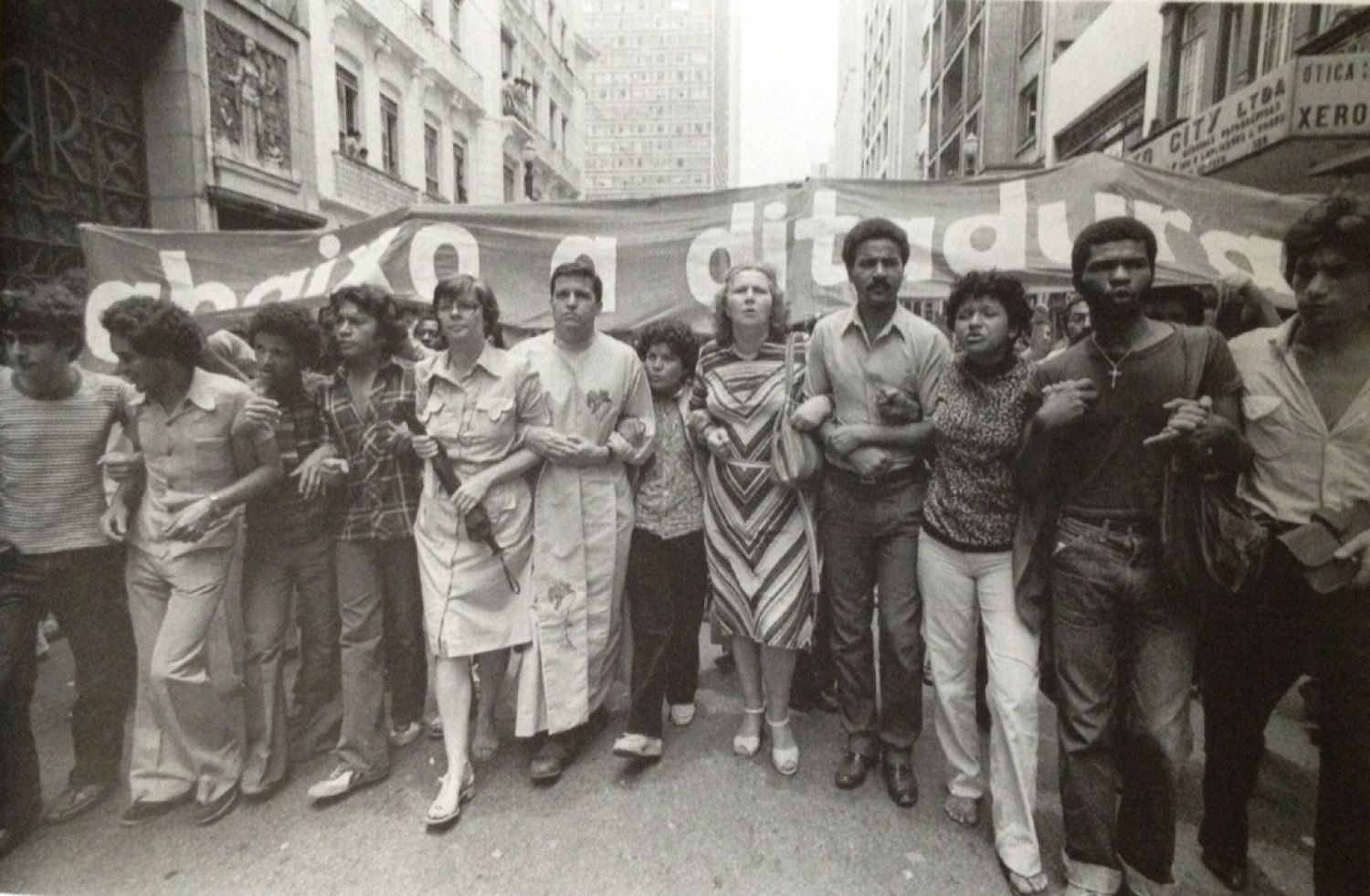

Besides the routine of workers on strike both photographers also documented some of the most discussed events of this period, such as the funeral procession of the worker Santo Dias da Silva. A military officer assassinated him on October 30, 1979 during a strike picket at the gate of the Sylvania factory, in São Paulo. On the following day his funeral procession spontaneously became a march going through several streets of the city, from Consolação Church, where his wake was held, to Sé Cathedral, where a funeral mass took place. Image 2 is a photograph made by Nair Benedicto showing the frontline of this funeral procession that rapidly became a big political manifestation against the dictatorship, gathering labour union leaders as well as members of the Catholic Church – Santo Dias was part of the Pastoral Operária, a branch of the Catholic Church that promoted the evangelization of the workers – and intellectuals. The image also shows a band where the political slogan «down with the dictatorship» is written.

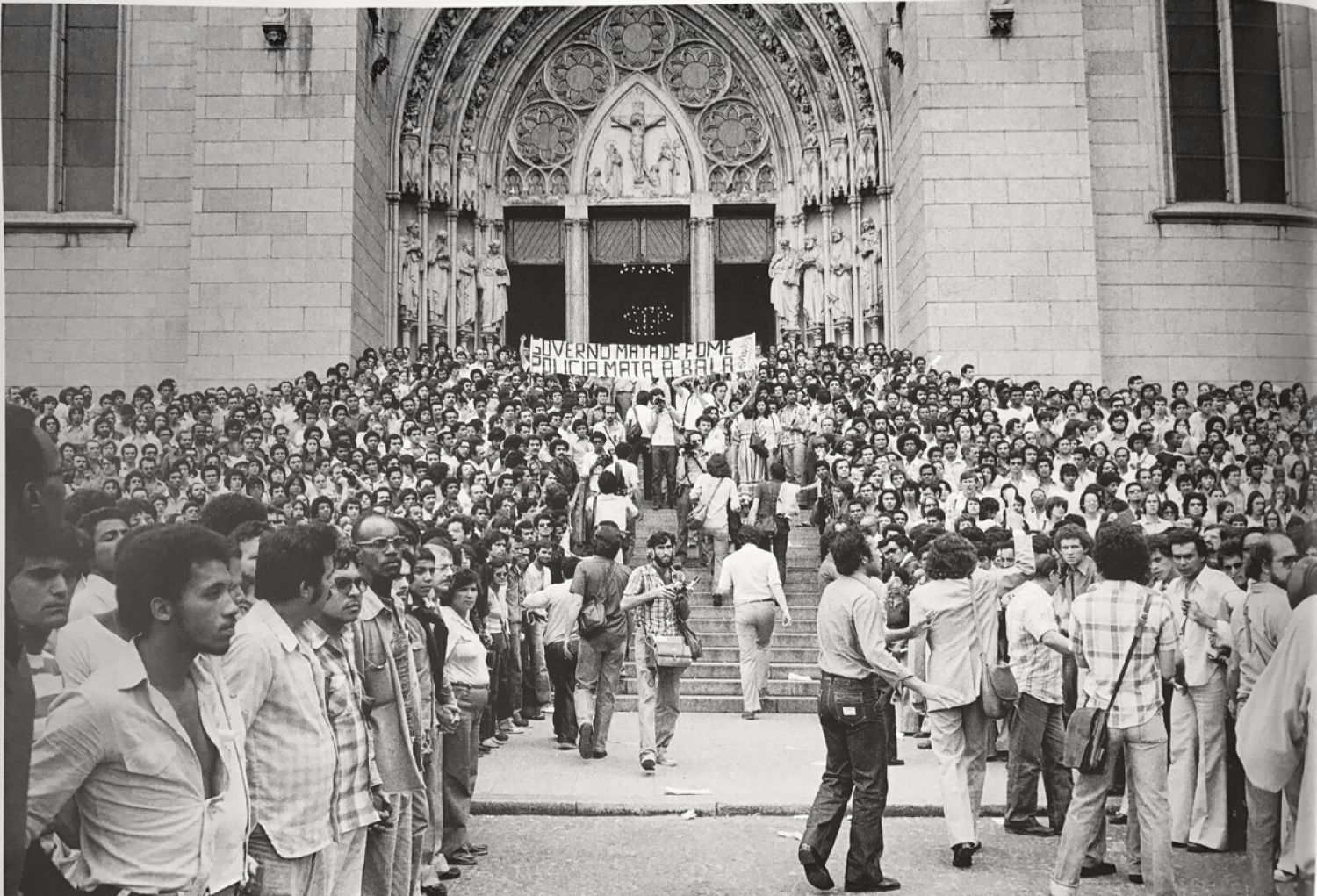

The wake, funeral procession, the funeral mass and the seventh day mass, also held at Sé Cathedral, as well as, one year later, the manifestations marking the assassination anniversary, were extensively documented by freelancer photographers, members of independent agencies or photographers working for the alternative press that opposed the regime. Image 3 shows the crowd gathered at Sé Cathedral gate for the worker’s funeral mass. In the background it is written on a band: «Government kills with starvation; police kills with bullets». It is possible to see in the empty space left by the crowd – probably for the passage of the coffin – several photographers documenting the gathering.

Catholic Church strong presence in the development of events as well as in the images of this period was not by chance. Soon after the coup and during the period of greater repression before 1975, Catholic Church’s most progressive branches – especially the followers of the Liberation Theology, closer to a Marxist discourse – had achieved great social penetration through the formation of the Basic Ecclesial Communities, or CEBs. Established after the Vatican Council II, they were small family nuclei gathered to discuss religious issues, but often ending up discussing also social issues and the political situation. For their significant amount and capillarity, especially in industrial areas, these CEBs performed a real base work, forming popular leaderships[4]. Supported by this network, ABC workers were able, with the progressive political opening, to get organized again and resume the union movement, which had been dismantled after the coup, culminating with the ABC strikes between 1978 and 1981.

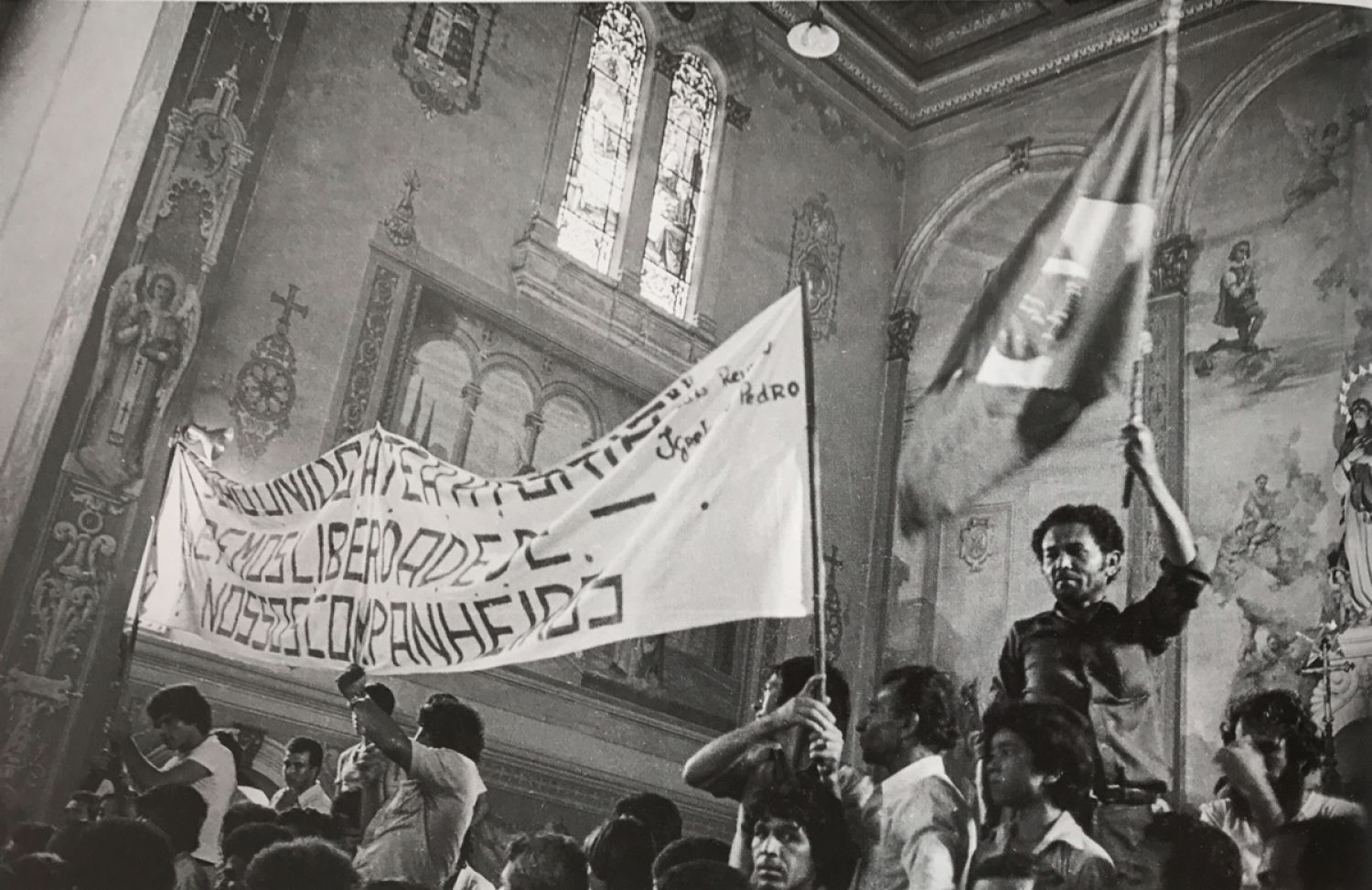

The Catholic Church was in many instances a place of shelter and refuge to regime opponents in general and to strikers in particular. When the Ministry of Labour determined an intervention operation in the ABC labour unions, the military police was sent to invade several union headquarters and arrest many of their leaders on April 17, 1980. Immediately, the Church allowed the remaining union members and supporters to gather in a permanent assembly at the Main Church of São Bernardo do Campo. Nair Benedicto’s photograph reproduced on Image 4 shows this inter-relationship between the workers organization and the Catholic Church. Made from an upward angle it shows a background composed of a very high-ceiling wall adorned by stained glasses and decorations representing saints and religious symbols contrasting to a foreground of mobilized workers holding a Brazilian flag and a band demanding the freedom of their arrested fellows. The standing man holding the Brazilian flag in the right corner of the image appears above all the others. He is beside a partially visible Jesus representation in the Church’s altar, cropped by the bled image.

Rosa Gauditano and Nair Benedicto’s lenses also captured the moments of greater tension during the repression to the strike movement. Gauditano had already photographed armed policemen repression, on horseback, on foot or by car, against workers picketing in front of Volkswagen factory in São Bernardo do Campo, in 1979. In 1980, she made Image 5, documenting the moment when the military police released gas bombs against strikers and the general population who were around the Main Church of São Bernardo do Campo. As the union headquarters was under governmental intervention, the workers gathered at the Main Church were trying to go out on a march celebrating the first of May.

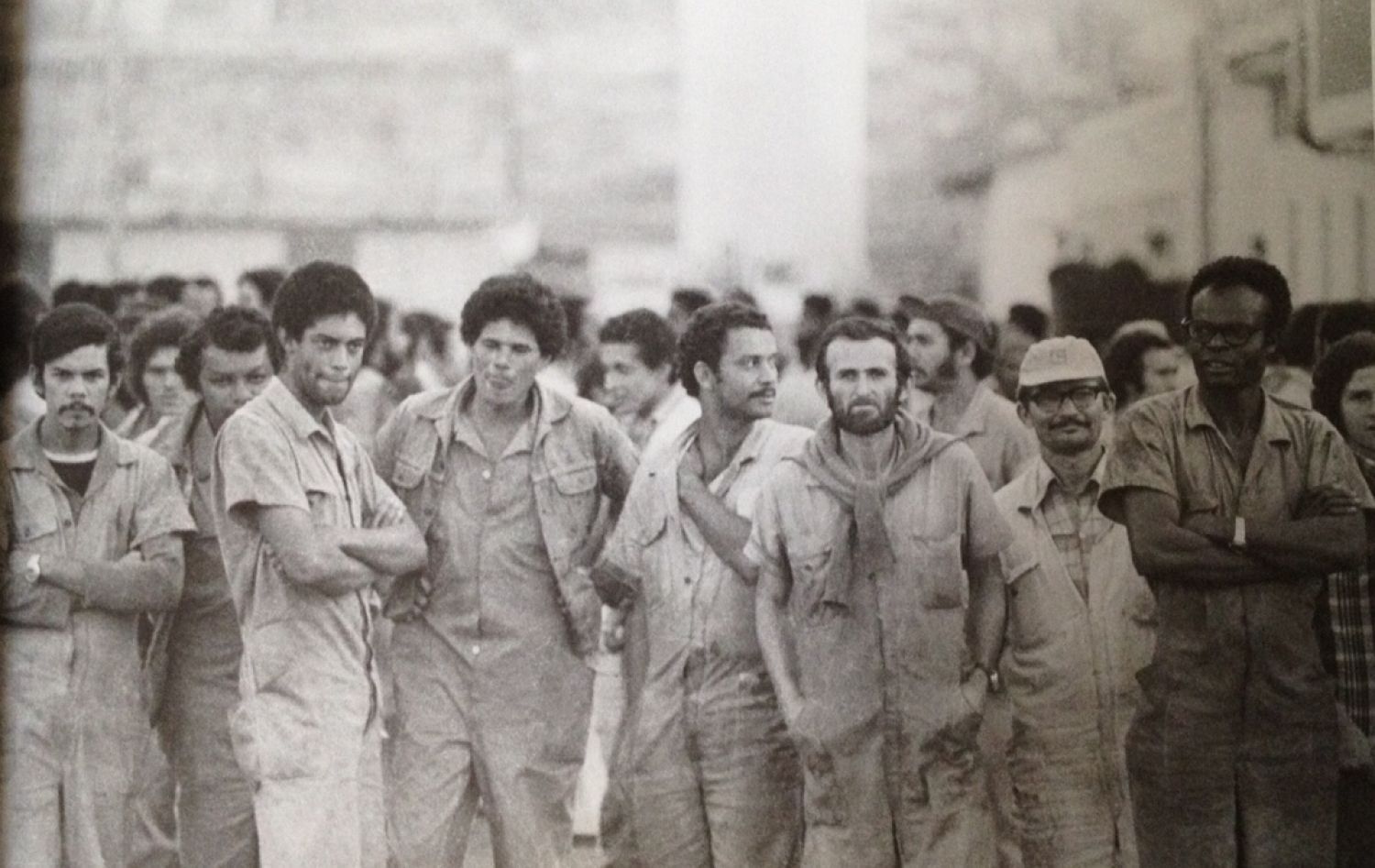

Most of Benedicto and Gauditano’s work about the 1978-81 strikes have a similar discourse. It is possible to see numerous images of crowds of anonymous people, from the working class, mobilized and united around common issues. These crowds are portrayed on close view, sometimes in a frontal eye level perspective, demonstrating the photographers’ presence amongst the workers, in the centre of events. The photographers’ political position is also unveiled. They are not simple observers any more but part of the mobilized mass. According to Adilson Ruiz, due to their political views and engagement many photographers who covered the 1978-81 ABC strikes, among them Benedicto and Gauditano, were able to infiltrate more easily «in the factory environment, in the strike pickets, and even boldly position themselves among the military police at the moments of repression to the workers. Being favourable to the mobilizations, they could also better position themselves in union environment, assemblies and strategic meetings»[5].

However, the images also portray the people in the communities and the workers families, all part of the same social mobilization. Therefore their images helped not only to form a visuality associated to the worker, the new social subject who had no historical or visual representation so far (Image 6), but also to their reality, their everyday life, their social class as a whole.

Alternative press and photographers organization

As a result of a rather autonomous process, these images circulated mainly in the alternative press that developed and gained prominence at that time. A large quantity of magazines and newspapers appeared with the gradual political opening determined by general Geisel from 1975. Some of them more precariously than others, they were produced and had small circulation, opposing the regime both politically, giving voice to left movements, and behaviourally, challenging the middle class morals. This press gathered experienced professionals who were victims of political purges and did not find space in the mainstream press, and young professionals recently graduated from university, often militants of left wing groups acting at the period. According to Bernardo Kucinsky, «The alternative press emerged from the articulation of two equally compulsive forces: the left wing desire to be at the avant-garde of the institutional transformations they proposed and the search, by journalists and intellectuals, of alternative spaces to the mainstream press and to the university. It is in the double opposition to the system represented by the military regime and to the limitations to the intellectual-journalistic production under the authoritarianism, that we find the link of this articulation among journalists, intellectuals and political activists»[6] – to those we would also add the photographers.

This alternative press was the only space to report more accurately the ABC worker strike movement, and it was responsible for the circulation of images like those by Gauditano and Benedicto. As it became a new and alternative public space, the alternative press enabled the dissemination and concretization of the visuality associated to the working class being created at that moment through photography.

Between 1975 and 1980 there were in São Paulo several newspapers with wider distribution at national level, like Movimento, Versus, Em Tempo, Nós Mulheres, and others more local, focusing on a determined region or district, like Jornal da Vila, ABCD Jornal, and O São Paulo, from São Paulo Metropolitan Curia. As a freelancer, Rosa Gauditano worked for the first four newspapers, and especially for Versus. Nair Benedicto founded and worked at Jornal da Vila until its was discontinued.

Marcos Faerman, a renowned journalist, founded Versus using his salary as an employee of mainstream newspapers, and for more than one year it was produced without proper machinery and was sold hand to hand. According to him, Versus was a «newspaper of stories, ideas and culture», where culture was seen «as a form of political action», and it was produced through the «fusion of elements freely used; journalism, photography, drawing, cartoons, literature, poetry»[7]. The newspaper was focused on cultural, historical and political themes regarding the different countries of Latin America, almost entirely under authoritarian regimes[8]. Versus was the first newspaper for which Gauditano worked, and she recalls it as a very fruitful period of apprenticeship, since she did not finish her university education. According to her, very young, starting her career, she came almost by chance to its newsroom, and was immediately invited to collaborate[9]. The experience must have been mutually beneficial, since by issue number 19, of March / April, 1978 – at the same time that the ABC strikes began – she appears in the credits as photography editor.

Nair Benedicto was part of a group of journalists and volunteers who gathered around Jornal da Vila. The newspaper's staff was mostly composed of journalists or volunteers fresh out of prison, most of them former members of the Ala Vermelha group. According to the photographer,

«Also, when I got out of prison, for example, I went to teach at the poor outskirts of São Paulo. We made a newspaper, which was called Jornal da Vila. We did a zone study, to know where it would be nice to act. Everyone coming out of jail. So I think this is incredible. I was extensively tortured; I got a kidney problem, which I have until today. But you would went out and said, ‘What are we going to do now?’ It was not, ‘Now I'm going home, to retire’. No, it was an idea that something must be done. So we left and just joined Lola's sister, the girl who is dead there [Benedicto photographed a female colleague student who was murdered by police during a demonstration], who thought something like ‘she died and I am here’. So it was something that triggered this in the people, the sensation that something had to be done. I had three children. I started looking at my children and thinking, ‘I do not want them to live in this country’. From there we did an analysis and we saw that a super nice region, which had nothing, was on the border of São Bernardo and São Paulo. There were poor districts called Vilas – Vila Moraes, etc. – and they had nothing, so we went to talk to the church staff to get there and do something.»[10]

The group of volunteers joined the Catholic Church to give courses to residents of some previously selected neighbourhoods on the border between São Paulo and São Bernardo do Campo, while producing and distributing Jornal da Vila. According to Laís Tapajós and Silvia Campolim, two journalists who were its editors, the aim was «to try to make a popular newspaper that was close to social movements, reflect on their experiences and contribute to their development». Jornal da Vila focused on these poor and working-class neighbourhoods, which had about 150,000 inhabitants, dealing with their specific problems, talking about popular movements and political discussions, but also about their prosaic daily life as a way to interest the population and win readers. They produced 26 issues of the paper for just over two years until June 1980 – the same period in which the ABC strikes occurred in that same region.

While Nair Benedicto and Rosa Gauditano worked in the alternative press reporting the labour movements and producing a specific visuality for these social actors who were organizing themselves politically, they also acted directly in the photographers’ struggle, who sought to organize themselves as a professional category. The professionalization of photojournalism in Brazil cannot therefore be seen separately from this generation photographers’ experience with social movements.

One of the first steps photographers took was, like the ABC metallurgists before them, to retake the unions that had been in the hands of people aligned with the regime since the coup. According to photographer Milton Guran, who worked in Brasilia in the late 1970s, this «Was a very rich moment because we tried to restructure the country under the dictatorship. So we tried to get the unions back. That was when the unions resumed [in Rio, São Paulo, Brasília]. (...) Also I was part of the group that founded in Brasilia a local branch of the Union of Photographers»[11].

Nair Benedcito and Rosa Gauditano were since the beginning assiduous members of São Paulo’s branch of the Union of Photographers. The discussions that took place focused mainly on the demands to maintenance of copyright and a common and fair price list for the sale of photographs. Those were claims regarding the work of independent photographers, as photographers working for the mainstream press signed a contract for the complete cession of rights to their images at the moment they were hired.

Thus, this Union of Photographers consisted of a group of independent photographers, freelancers or members of independent agencies, who met weekly to discuss pertinent issues to the category. According to Rosa Gauditano, it was the same group that worked for the alternative press that got to know each other because they met covering the same stories[12]. This attests to the importance of the alternative press, which despite being modest in scope and financial resources was able to help develop a consumer market for these independent photographers.

Through the Union of Photographers, Benedicto, Gauditano and other photographers hired a lawyer, who drafted a concession contract, and no longer cession of rights, guaranteeing for photographers the maintenance of copyright. They also hired an economist to help calculate a basic and common price list for selling the photographs independently. They then took these two documents to the Union of Journalists, who then adopted them as a model for the category[13].

As part of the fight for rights and professional recognition, many of the photographers of this generation have chosen to join independent agencies. This was the case of Benedicto, who in 1979 founded, with three other photographers, the F4 agency in São Paulo. The following year, Milton Guran participated in the founding of Ágil Fotojornalismo agency in Brasilia. Gauditano founded Fotograma in São Paulo in 1987. In their testimonies, these photographers constantly refer to the French agencies, especially Magnum, founded in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, as their inspiration. Speaking about the experience in the Union of Photographers, Rosa Gauditano said: «At that time we started discussing copyright. And nobody really knew what to do to be respected. And we had as reference the French photography agencies. Magnum, mainly»[14].

Milton Guran associates the photographers struggle for independence and professional recognition, also inspired by Magnum, with the political moment of gradual political opening and ABC workers’ organization. According to him, those claims could be related to

«(...) Magnum’s formation, the mythical agency. So the imaginary of the documentary photographer, the photojournalist, has always been impregnated with the agencies and the photographers' cooperatives. And we lived a very difficult situation in the late 1970s, early 1980s. There was a great pressure from society. The dictatorship was engaging in Geisel’s so-called slow and gradual opening, because of course it was inevitable.

(...) And society began to reorganize. The student movement began to restructure itself. In 1979 we had the UNE [National Union of Students] congress, the ABC’s strikes began. Then there was a great deal of pressure for real, not official, lying information given by the dictatorship. For independent journalistic stories, and not employer’s guidelines, since the press was all co-opted by the regime. [The independent agencies] were the instrument we had in order to have our own stories, to be the owners of our negatives, and at the same time to escape from a condition of bóia-fria [rural day worker] in which we were placed in the labour market, with depreciated wages (…). This situation created the conditions for us to start organizing independent agencies. And the agencies were being created at the same time that we launched ourselves in our own stories, and that we launched ourselves in the organization of the defence of the photographic copyright, a minimum price list. Especially in Brasília, in São Paulo, in Rio de Janeiro, in Rio Grande do Sul, a little in Espírito Santo. And it was spreading throughout Brazil. And there, well, that's the story. I became involved in this movement.»[15]

Final considerations

During the second half of the 1970s, the field of photography in Brazil underwent some relevant transformations. It started been incorporated into museum collections and exhibited in individual or thematic exhibitions[16]. It was also taught, promoted and historicized by governmental institutions since the creation of FUNARTE, National Foundation of the Arts, in 1975, and more specifically in 1979, with the creation of the Núcleo de Fotografia da FUNARTE [FUNARTE’s Photography Center][17]. At the same time, Brazilian photojournalism became professionalized, mostly due to the independent photographers’ struggle[18].

During the period of the ABC strikes, Benedict and Gauditano witnessed the results of the workers' organization, while at the same time participating directly in the process of organizing photographers as a professional category. From São Paulo’s ABC workers organization a union movement was consolidated that, in the following years, would form a working-class party, the first of its kind in Brazil. In the same way, during the process of the photographers organization, photographic agencies and working methods were created that became decisive for the history of Brazilian photography.

The photographic work that Rosa Gauditano and Nair Benedicto created documenting the troubled political period in which the ABC strikes that took place between 1978 and 1981 helped to establish a specific visuality for new social subjects that still did not have space of representation – especially the factory worker and the working class. Their eloquent images focus on anonymous people united in a common struggle, individual faces and bodies that come together to gain strength and cope against the dominant, usually faceless, power. In this sense, these are images that bring a humanist discourse. They show the photographer’s solidarity to the workers and a political «concern»[19]. After that troubled period had passed, Benedicto’s and Gauditano’s photographic work maintained its humanistic-related social engagement through themes common to both: social minorities and dominated populations like women, blacks, gays and indigenous people.

In choosing to photographically document this historical moment, Nair Benedicto and Rosa Gauditano undertook a double struggle. If we return to Image 3, the entrance to Sé Cathedral, we can count at least seven people with cameras professionally documenting the event. All of them were men. Benedicto would come to recognize, without going into detail, that the independent photojournalism environment had a rather accentuated patriarchal behaviour[20].

Gauditano emphasized the absence of women in this environment. According to her, «I have been opening doors... Not with [social] movements. I've been opening doors in the press. I was one of the few women. I do not remember other women who were there. It was me and Nair, who usually photographed these things. There was one more girl who was from São Bernardo. Then came Cristina [Vilares] (...). We were few. All freelancers»[21]. What seems to startle her was not the absence of women in the workers’ strike, obviously a male movement at the time, but the absence of women in photojournalism. We can guess there was some sort of resistance, since she had to struggle to help opening doors for her and her female colleagues to enter their professional careers.

Thus, acting in a predominantly male environment, those women were able to register one of the most important moments in the history of the Brazilian worker movement, producing important historical documents, which, through time, came to represent the historic event itself.

Bibliography

AGUIAR, Carly. «CEBs: Comunic(ação) e identidade social». in GOMES, Pedro, PIVA, Márcia (orgs). (1988). Políticas de comunicação, participação popular. São Paulo: Paulinas.

BARROS FILHO, Omar de. (2007). Versus. Páginas da utopia. Rio de Janeiro: Beco do Azougue.

CAPA, Cornell (ed). (1968) The Concerned Photographer. The photographs of Werner Bischof, Robert Capa, David Seymour, Andre Kertesz, Leonard Freed, Dan Weiner. New York: Grossman Publishers.

COSTA, Eduardo, ZERWES, Erika. (2015). «The Dialogical Construction of a Historical and Photographic Narrative in Brazil and Latin America between the 1970s and 1980s» in International Journal of History and Cultural Studies (IJHCS), Volume 1, Issue 3.

COSTA, Helouise. (2008). «Da fotografia como arte à arte como fotografia: a experiência do Museu de Arte Contemporânea da USP na década de 1970» in Anais do Museu Paulista. São Paulo. Vol.16, n.º 2, pp. 131-173.

FERNANDES JUNIOR, Rubens. «Juca Martins: a eterna paixão pela aventura humana» in LUZ, Afonso, SIQUEIRA, Henrique. Juca Martins. (2015) São Paulo: Martins Fontes.

KOTSCHO, Ricardo, Agência F4. (1980). Documento. A greve do ABC. São Paulo: Caraguatá.

KUCINSKY, Bernardo. (1991). Jornalistas e Revolucionários. Nos tempos da imprensa alternativa. São Paulo: Página Aberta.

LIMA, Ivan, RIPPER, João, AZOURY, Ricardo. (1982). Sobre Fotografia. Rio de Janeiro: Sindicato dos Jornalistas/FUNARTE.

MAGALHÃES, Angela, PEREGRINO, Nadja Fonseca. (2004). Fotografia no Brasil: um olhar das origens ao contemporâneo. Rio de Janeiro: Funarte.

PAIVA, Joaquim. (1989). Olhares Refletidos. Diálogo com 25 fotógrafos brasileiros. Rio de Janeiro: Dazibao.

RUIZ, Adilson. «Fotógrafos em ação» in RUIZ, Adilson, BRAUNS, Ennio (orgs) (2016). Máquinas Paradas, Fotógrafos em Ação. São Paulo: Fundação Perseu Abramo.

ZERWES, Erika. «Os dois lados da moeda. Humanismo e militância em Claudia Andujar e Nair Benedicto» in BRANDÃO, Angela, DRIEN, Marcela; TATSCH, Flavia Galli (orgs). (2017). Política(s) na História da Arte: redes, contextos e discursos de mudança. São Paulo: Programa de Pós Graduação em História da Arte, UNIFESP.

ZERWES, Erika. «A fotografia humanista e a América Latina: aproximações e mediações artístico-culturais» in FREIRE, M. C. M. (org). (2016). Escrita da História e (re)construção das memórias: arte e arquivos em debate. São Paulo: Annablume.

Footnotes