r

e

v

e

s

Genesis of an artistic activism

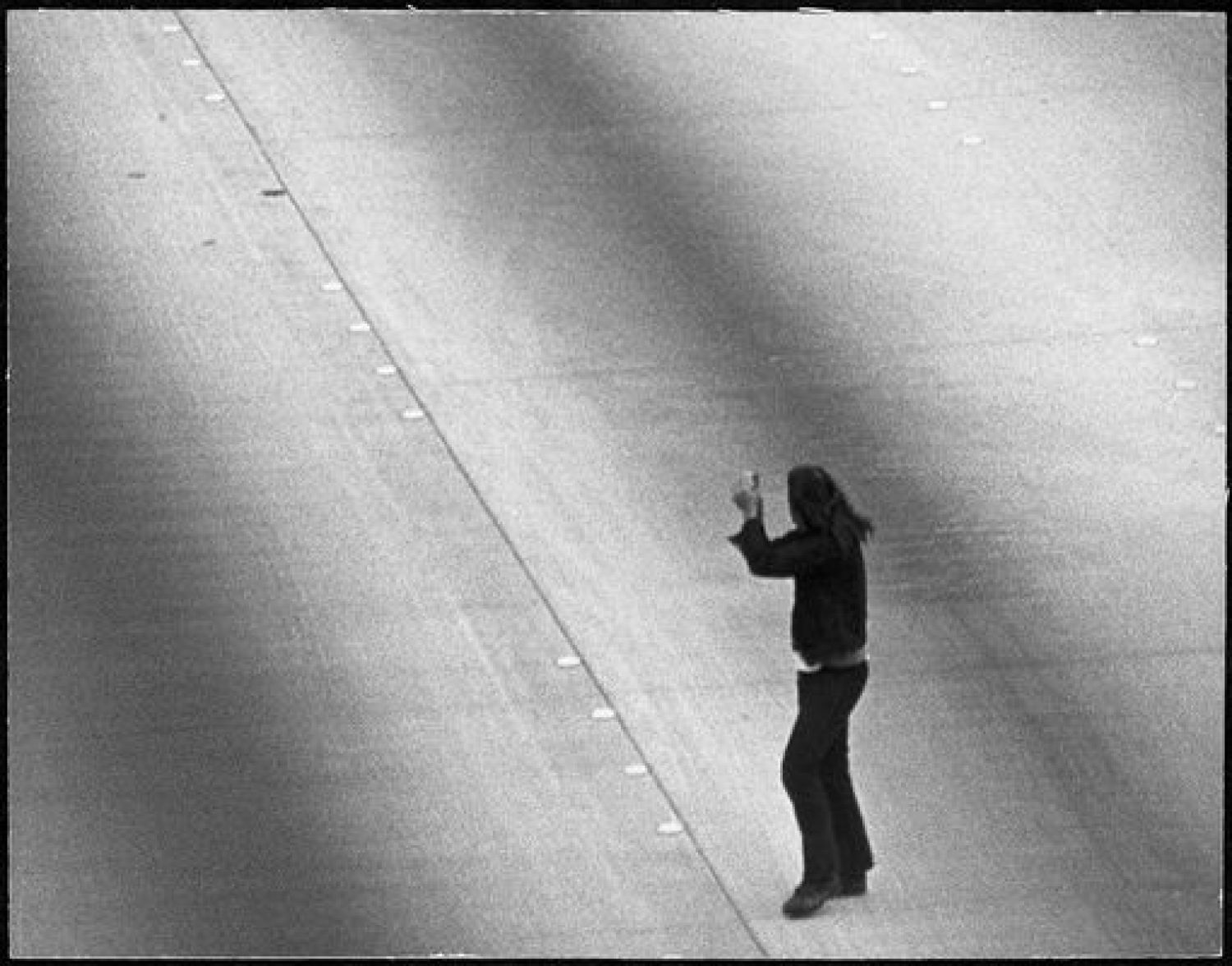

In order to retrace the origin of Sekula's artistic activism a well as to properly understand it, we propose to go back to his artistic debut. In 1972, Sekula was attending the University of San Diego, California, with a major in Visual Arts. From that year, he began a committed work on photography as a critical document. Box car (1972) is the first of his youth works. It consists in a photograph made from the open door of a rail-freight wagon as it passed a chemical research and development plant where the young Sekula had worked as a technician more than two years earlier. The theme of the factory work will never abandon Sekula's practice and reflexion since then. With Meat Mass (1972), he integrated the photographic medium to the artistic and political performance. This one consists in a series of 12 black-and-white photographs with which Sekula documented the thief of expensive meat pieces from a supermarket and the political gesture of throwing them under the wheels of crowded traffic lanes.

At the end of the sequence, we see him leaving the performance's ground-flour by running up the Californian hills nearby.

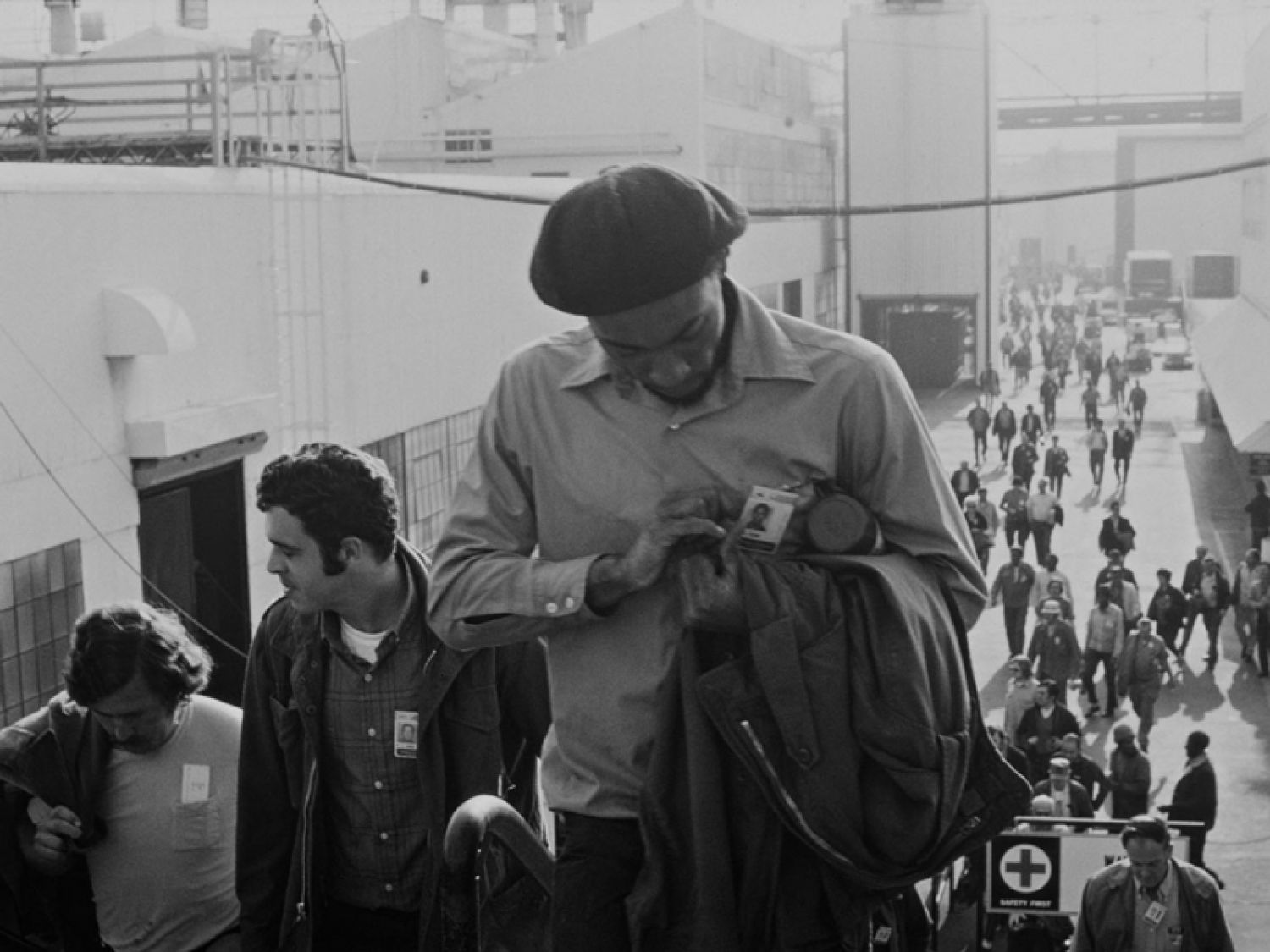

But is is only with Untitled Slide Sequence (1972) that a proper consciousness of the role of photographic documents grew. The difference between this one and his other previous works could seem of little importance: it is a slide sequence of 24 black-and-white photographs projected in a loop with a 13-second-interval for a total duration of 17 minutes, 20 seconds. The sequence is taken at the entrance of the Convair Division aerospace factory at the end of a working day.

Sekula had been documenting with a Nikon camera borrowed from a friend the workers leaving the firm but, standing within the gates, he finally gathered the security guards' attention so that at the end he was forced to leave his location. Fortunately, he managed to take at least the 25 pictures which then became part of the slide sequence.

This is also the reason why the last pictures don't present a front perspective as the rest of them: Sekula was then on the same level than the workers leaving and the sequence actually ends with a photogram of the ground. As we can suppose, he was finally forced to stop taking photos. In particular, we argue that this work contains in nuce some of the major themes then developed by Sekula throughout his career but also some extremely interesting original elements.

First of all, as the author described it during the interview given to American art historian Benjamin H.D. Buchloh between the 24 and the 26 of January 2003 in New York City and published in the catalogue of Performance under working conditions, all these three first works shared a performative dimension. But the artist reported: «I was convinced that documentation was more interesting than the action itself. There was something appealing and autonomous about the sequence of images.» (Allan Sekula, Performance under working conditions, 2003, p. 21). The sentence witnesses a precocious interest in the photographic properties that brought Sekula to privileged them to the performance itself. Thus, Untitled Slide Sequence establishes an original antinomy between documentation and action, the first one of a long series of oppositions that perfectly matches Sekula's deep interest in diptychs and dialectical triptychs forms. As it is the case for the study titled Meditations on a Triptych (1973-78).

Secondly, the subject of Untitled Slide Sequence isn't that original, as it refers to the cinema's primitive scene: Workers leaving Lumière factory in Lyon by Louis Lumière (original title: La sortie de l'usine Lumière à Lyon, 35mm, 45sec, 1895). Although we can't consider it the first film of the history, because the invention of the Kinetoscope by Thomas Edison preceded it, Workers leaving Lumière factory in Lyon is undoubtedly the very first sequence realised by using the cinematograph, whose invention belongs to the Lumière brothers. There are three different versions of this 45 second film, only the first of them was originally shoot by Lumière at the end of a working day. The other two were actually filmed on a Sunday after the mass, a detail that can be told since workers aren't wearing working clothes in there.

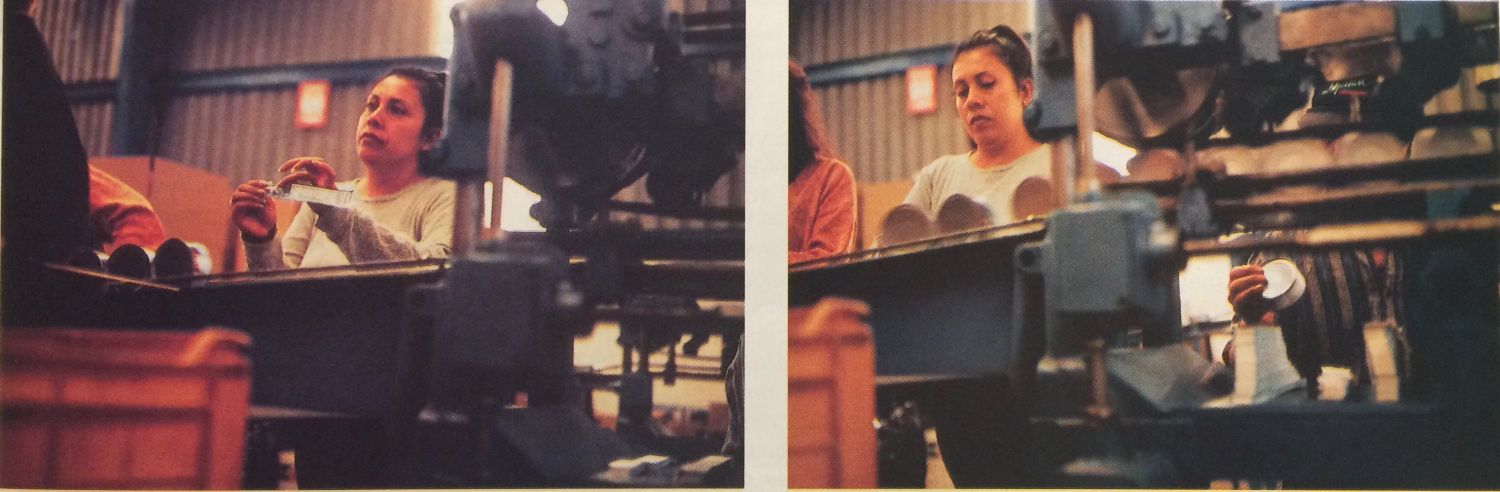

Moreover, only in the second and third version all the folk is seen leaving the factory, when finally the doors are closed. If the scene's frontal perspective is pretty the same, in Untitled Slide Sequence the photograph is inside the factory, recording the leaving of workers from blue collars, wearing casual clothes, to groups of women and white collars in smart suits, probably the firm's engineers and managers. On the other side, in its cinematographic original version, Workers leaving Lumière factory in Lyon, most male and female workers, except from some office employees and a dog, probably belong to the same social class, whereas in the film's second version dated 1896, only the alleged chief executer office leaves the factory in a horse-drawn carriage, while all the others workers are on foot, except from some of them riding bicycles. Again, in Untitled Slide Sequence the choice of the factory's aerospace field is not casual. Since his father was an aerospace engineer, Sekula would then decide to focus on this specific industrial sector in Aerospace Folktales (1973), before consecrating himself entirely to the maritime work. Work and, more specifically, factory work are Sekula's main social interest in his early years, as we've seen in Box Car (1972), for instance. Since the beginning, Sekula decided to use the photographic documentary form as a social project. By using the social photography as an artistic commitment, he intended to provoke public debate about the deep social differences in the American post-industrial, advanced capitalistic mass society. We should mention for example the critique he carried with Attempt to correlate social class with elevation above main harbor channel (San Pedro, July 1975), which is part of California Stories (1975-2011).

Anyway, if Sekula has always stood on the side of the most underprivileged social classes as the dockers, he has never forced himself to stick to the same identical point of view. This is why for Aerospace Folktales (1973), he decided to focus on the biographical problem of the unemployment on highbrow social classes (an aerospace engineer and his family).

Secondly, by displaying workers leaving the factory in the form of a slide sequence, Sekula intended to show a file rouge between the photographic procedure and cinema history, which are, together with the critical theory, his three favourite mediums. In Untitled Slide Sequence, photography and cinema are entangled both by the choice of the subject, which refers to the cinema's original scene, and the more formal aspects, the procedure of the slide sequence that can be seen as a primitive cinematographic form too. 25 pictures are showed in a loop, with 13 seconds of interval between each sequence and another. In addition to this, Sekula adds to the visual material a textual support, «Workers leaving the factory at the end of a day shift», this way getting closer to the form of the disassembled movie, which reached its accomplishment with Aerospace Folktales. Indeed, the presence of the text in Sekula's art pieces is never naïve. Starting from Meat Mass, he questioned the relationship between the performance and the document. Sekula then added to the debate on the photographic medium another dialectical couple: the visual material from one side, and the critical text, from the other. Images and words, as well as actions and documents, aren't considered in a hierarchical, exclusive way. Besides, Sekula insists in recognising to both sides of these dialectical figures the same status and dignity and thus in stating their autonomous identities. «While in general I thought of my critical writing as opening potential paths for alternate possibilities of practice, I was not interested in making this an explicit or programmatic charting of course. I wanted my own photographic projects to be reasonably legible without demanding recourse to a separate and supplemental theoretical text.» (Allan Sekula, Performance under working conditions, 2003, p. 25). Alongside with a social critique, Sekula wants to subvert the traditional dichotomy between theory and practice, so that, from the very beginning of his career, different elements are assembled in his works: performances, written and oral texts, records and sound montages and, of course, pictures.

The temporal dimension of the interval as a critical project

If we insist on Untitled Slide Sequence is because the editing Sekula chose to use in this work is quite significant and, as we argue, has a critical meaning. Indeed, in a interview with Pascal Beausse, Sekula points the question of his critical realism in these terms: «The problem of critical realism is this: how do we find the interval within which the idea of freedom resides?» (Art Press 240, Nov. 1998, p. 26). We believe that the way in which Untitled Slide Sequence is realised can answer precisely to the question of freedom referred to the factory work. The loop's form is repetitive par excellence, always showing the same length (17min 20sec) and then irremediably displaying itself again and again. But to this reiterated circularity, the author intervenes with regular, abrupt interruptions: every 13 seconds the narration is stopped. And then, it resumes one more. Thus, we should interpret these formal aspects as a reference to another highly repetitive but syncopate movement, infinitely repeated: the factory work at the chain. This way, the photographic medium acts exactly as the worker and points out an interrogative concerning the critical function and meaning of the interval itself.

However, the insistence on the temporal syncopated form has at least a previous example in performative arts. I am speaking about Brecht's epic theatre. The Brechtian theatre, whose structure is dialectical, rather than presenting long scenes which emotionally involve the public, is mainly organised in jerks, as they were cinematographic sequences. At the very beginning of Extract of an ABC on epic theatre, Brecht claims: «In the epic theatre, cinema gets a great importance.» (Bertolt Brecht, Écrits sur le théâtre, p. 202). And Benjamin adds: «Its basic form is the shock, by which particular situations of the piece, quite distinct from each other, would collide.» (Walter Benjamin, Essais sur Brecht, p. 60). In this way, between one sequence and another, the interval offers to the spectators the place, and time, for the reflection and the critique. Of course, this strategy for Brecht is more than narrative but has a political meaning. It corresponds to the proposition with which Walter Benjamin, that Sekula read since his young age, ends The work of art in the age of its technological reproducibility (1939). As a response to the mass alienation following the extent of the industrial reproduction from one side, and the rising of Nazi totalitarian regime from the other, the German philosopher and critic, forced as Brecht to go into exil, replies: «Such is the aestheticizing of politics, as practiced by fascism. Communism replies by politicizing art.» (Walter Benjamin, The work of art in the age of its technological reproducibility, p. 42). Indeed, according to Benjamin, the project of a politicisation of art can be carried only by those new forms of art, photography and cinema, which were introduced and then infinitely reproduced thanks to the technological innovations. However, as we know, his thesis is highly dialectical. From one side, art has lost forever its auratic dimension that has permitted for centuries to be singularly contemplated. It is interesting though that the concept of aura in Benjamin has a spatiotemporal dimension, as he defines it as the spatiotemporal unicity of a work of art. Once the aura is fatally lost because of the possibilities given by the technique to infinitely reproduce a work of art, which doesn't exist anymore in an hic et nunc, however, there is still a positive value that belongs to the artistic creation. And it is, precisely, its political value. To Benjamin, the cinema, whose reception is for the first time consistently collective and simultaneous, offers to the public a new perception of reality. Films contribute to form in the spectators a new critical and political consciousness. In particular, Benjamin believes that through the cinema, and in general through the new reproducible works of art, an emancipated community who acts for a radical change of reality is finally constituted. With the cinema, the critical public opinion is born. And according to Brecht, the epic theatre, which is mostly inspired by the film's editing process, awakes the spectator's intellectual activity, his critical sense and transforms his feelings into knowledges. Brecht's theatre is anti-aristotelean because it flees any identification with the spectatorship, any emotional engagement, any catharsis. «With ‘epic’ we intend the calm, the flow, a certain objectivity, a tonality devoid of passions, a discourse which we listen to with a minimal psychological excitation.» (Bertolt Brecht, Écrits sur le théâtre, p. 229). If, from one side, the dramatic theatre is defined as «the theatre of culture and distraction» (Benjamin, Essais sur Brecht, p. 119), from the other, the progressive, didactic, anti-dogmatic marxist scene of the epic theatre is sober and directly confronted to the technique. Its nature is essentially critical, as like Brecht states: «The epic theatre doesn't fight emotions but, instead of being limited to arise them, it looks into them.» (Bertolt Brecht, Écrits sur le théâtre, p. 230). According to Benjamin, the role that the gesture holds on the Brechtian scene corresponds to the function of the editing process in radio and cinema, when a technical operation is transformed into a human event. Thus, the principle of epic theatre and of cinematographic montage is the dialectical interruption. The peculiarity is that, in a progressive theatre, the interruption has a pedagogical value. In this optic, we must stop an action to release its human, living material. This interruption allows the viewer to distance himself from the action, on the one hand, but also the actor from his role, on the other. With the epic theatre, mankind is understood compared to the political crisis that, from the thirties, crosses, starting from Europe, the entire world. Thus, the scene of the culture (Bildung) and of the entertainment, is transformed into the scene of the formation (Schulung) as an education in critical judgment and collective association.

Now, this authentic dimension can be reached only if the public is prevent from being emotionally involved in the story and if he is encouraged to assume a critical posture. This is the reason why the temporal interruption has such an important role in Brecht's theatre, a role which corresponds, in Benjamin's theory on cinema, to the shock effect capable to awake the public consciousness. Indeed, the accent on the temporal dimension is also given by Sekula himself in answering to the question of freedom within the critical realism. Freedom of thought and practice can be found, despite the massive alienation processes, «By careful attention to time, realizing that the camera too often kills and obscures lived time. Photoshop is of no help here» (Art Press 240, Nov. 1998, p. 26). While the machine obliges the worker to follow a strict sequence of movements, by imposing the controlled and administrated time of the assembly line, the interval reveals an original spatiotemporal dimension, that we argue being that same authentic dimension Brecht wanted to create with the dialectical epic theatre. By stopping the inexorable machine, only the interruption in time let the worker being aware of his personal consciousness and his critical power. This way, the interval could be the genuine time-space of freedom in an era of high technicality, uncontrolled mechanical reproduction, mass consumerism and globalised work.

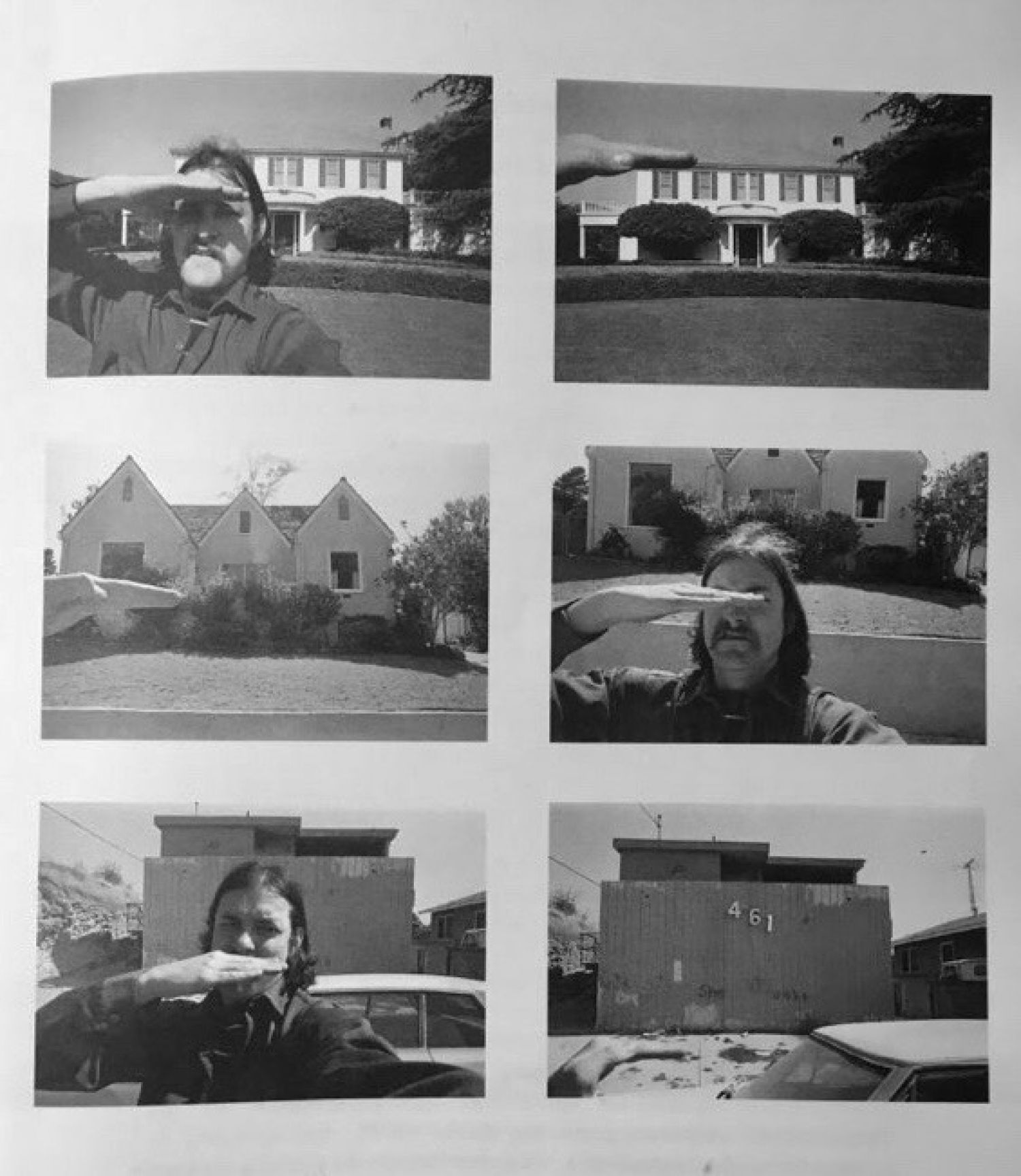

We should notice that among the already mentioned early works, Aerospace Folktales (1973) seems to reach an accomplished step in this same direction. The 142 black-and-white photographs and text cards are this time accompanied by four sound recordings. First of all, the subject, again, witnesses of Sekula's social engagement. At its peak in 1967, Southern California aerospace industry assured almost half a million jobs. But the economic recession that followed the Vietnam war brought a consistent unemployment that hit the middle and high social classes as well the lower classes. We then found out that this sequence, which follows the family of an unemployed aerospace engineer, is in fact about the artist's family, whose father had lost his job during the early 1970s'. Thus, Aerospace Folktales answers to a social problem but has also an autobiographic value. Moreover, it represents for Sekula his first attempt to deal with a critique of the history of photography. The three social, familiar and photographic dimensions coexist. «I was looking for the founding myths and antinomies of institutional photographic discourse, as well as the legitimation and self-justification in family life: the realist and symbolist ‘folk-myths’ of photography and the ‘folktales of the family’.» (Allan Sekula, Performance under working conditions, 2003, p. 25). The more he investigated in high-classes unemployment, the more Sekula fatally discovered how deeply his own family was built on social predicted logics. Concerning the formal aspects, at the occasion of its first installation at the University of California, San Diego, Aerospace Folktales was conceived as a flow of photographs whit texts interrupting the series, as the artist was recreating the narrative flow and the format of a silent movie. Again, the interval had a significant role. But, as an integrated part of the project, there were this time also four sound recordings that were played in an adjacent room, while Sekula performed a reading of a seven page commentary text. Later, the recordings would be placed in the same room as the pictures and text cards, whereas in the final version of Aerospace Folktales, published in 1984 for the first version of Photography against the grain, Sekula reduced the photographs to 51, grouped in diptychs or groups of four, and the sound recordings to three. Speaking of this new element, Sekula explained: «My interest in the documentary photographic portrait overlapped with an equally strong interest in the tape recorded speech.» (Allan Sekula, Performance under working conditions, 2003, p. 24). The original four recordings contain the interviews Sekula made to the husband and his wife (the artist's parents) as well as with a friend of theirs, whose husband was unemployed too. As he recalled in the suite of the interview with Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, Sekula started to be interested in the recording's practice very early in age. «The nascent idea of a dialectical editing of social speech seems to have occurred to me early on. I might well have been influenced in this by some of the underground ‘sound montages’ that were played late at night during the sixties on Los Angeles radio station KPFK, which was a lifeline to dissent for my generation» (Allan Sekula, Performance under working conditions, 2003, p. 24). Indeed, these first experimentations with the editing of social speeches ended in the work titled Gallery Voice Montage, which dates back to 1970. It is especially from the practice and the meditation over the montage of visual, textual and sound materials that then Sekula came out with the revolutionary idea of the disassembled movie. Firstly, the disassembled movie is based on temporal interruptions operated by intervals. Thus, it results in a series of sequences, separated from each other, and at the same time belonging to the same flux of ideas, sounds and images. Secondly, as a consequence, the disassembled movie is an hybrid object. While Sekula seems to put the accent on its temporal dimension, the name itself refers to the exercise of decomposing, dissecting and of separating every single component. Not with a scientific approach but in a social and critical intention, each element of the movie is displayed autonomously, by keeping at the same time its relationship with the others. «Committed to the idea that a photographic project was of necessity a matter of editing and sequencing, a parallel tracks for voice and image and text, more or less the strategy of the ‘disassembled movie’…» (Allan Sekula, Performance under working conditions, 2003, p. 25). However, it is speaking specifically about Aerospace Folktales that Sekula used for the first time this neologism. «This ‘disassembled movie’ would in this case function as an extended portrait, not of an autonomous individual, but of a family member in relation to one another and to the structuring of the familial institution trough ideology and socialisation. To link the sort of micro-sociological observations to a broader context.» (Allan Sekula, Performance under working conditions, 2003, p. 25). In this case, each member of the family stands alone, regarding to his social condition, his role and his activity, but at the same time each one is considered in relation to the other members.

While Sekula considered the consequences of the husband and father's unemployment over the family, he intended to study the impacts of the social environment and of the '70s consumeristic American culture over the family's microstructure. So, he decided to include this dialectical movement (from the individual to the familiar institution and from the society to the family) also in the artwork's formal aspects, where each visual, textual and acoustic material stands by itself as if it was the case of a dissected (disassembled) movie. There is no hierarchy, each part is worth another but at the same time they are all offered to the public so that the spectator can analyse each of them accurately and separately.

The program of a photography against the grain

In two of his seminal critical essays, Sekula seems to trace, in a programmatic way, his project of a photography that he defines «against the grain» (Allan Sekula, Écrits sur la photographie, p. 51). I am referring in particular to Dismantling modernism, reinventing documentary: notes on the politics of representation (1977-78) and to Photography against the grain, an introduction (1984), that I propose to read together as if they were Sekula's manifesto for a documentary photography intended as an artistic commitment. These two texts allow to outline a complete frame on Sekula's beginnings, opening to the most recent part of his work. To start, we should consider the double identity of this artist, who can be considered at the same time an engaged activist, form one side, and, from the other, a photography critic.

First of all, I think we should mention the essential matter of social dependance, which drive both Sekula's critical and practical works. His aim is, by the means of his texts, performances and artworks, to provoke conflicts with the huge technical, economic and mass consumption's system and to transform reality. Sekula's texts, images and actions do want to create a social consciousness through both the artistic and critical means, in order to overcome the modernist elitism of a pure art. In this sense, Sekula's intention is diametrically opposite to the critical theory of Adorno, who considered that art should remain apolitical, while being critical, and who denied any possible pragmatic use of artistic works. Indeed, Sekula's position would definitely be more closed to Benjamin's critical posture and his project of an effective politicisation of art, as suggested in The work of art in the age of its technological reproducibility. The project of a politicisation of the practice must lead, according to Sekula, to the rehabilitation of pragmatism, which was left besides by modernism, and to constitute a critical figurative art. «A critical figurative art, an art that would refer openly to the social world and to the possibility of a concrete social transformation can be developed from here.» (Allan Sekula, Écrits sur la photographie, p. 146-47). Yet, the rehabilitation of pragmatism should convey an educational effort, as Brecht suggested in his project of epic theatre, as well as a real fight against current orders. «At the same time, we must redefine a pragmatism, a method of relation founded on a pedagogic dialogue and try to significantly broaden the notion of public, by associating the current struggle against the established order» (Allan Sekula, Écrits sur la photographie, p. 147). Speaking this time about Aerospace Folktales in 2003, Sekula insisted again on the context-dependance by claiming that, moving against modernism and its auto-referential ideal of l'art pour l'art, it has become «urgent to reintroduce the social dimension that had been repressed.» (Allan Sekula, Performance under working conditions, 2003, p. 25).

So, the major problem of modernism is, according to Sekula, an «illusive ideology of neutrality» (Allan Sekula, Écrits sur la photographie, p. 145), that has leaded to a categorical refusal of every political implication. Now, the reduction of all practice to formalism, as operated by modernism, is built on the radical division between theory and practice. In this sense, the photography's critical programme of Sekula aims at rethinking the presumed hierarchy of theoretical and practical work by showing that the division is nothing but the consequence of the discrimination between intellectual and manual work introduced during the modern period in political economics. In Dismantling modernism, Sekula points his finger at the arrogant and elitist critique, born together with the aspiration of the middle bourgeoise: «To engage into a cultural practice which is openly political, artists and writers must leave their professional elitism and the narrowness of their preoccupations.» (Allan Sekula, Écrits sur la photographie, p. 145). Yet, to the author, modernism is, in se, self-destructive. Its excessive formalism, together with an ideology of neutrality, auto-referentiality and elitism have spontaneously leaded to «the cafeteria of post-modernism» (Allan Sekula, Écrits sur la photographie, p. 54), where every historical moment is indistinctly accessible, totally disconnected from its context. The crisis in contemporary art and culture, that affects photography as well, which, in the attempt to maintain an highbrow exclusive status has recycled Benjamin's notion of aura (I.g. with the restrictions in photographic print and the auto-proclamation of authorship), is mainly due to the abandon of the practice, in favour of the pure theoretical exercise. However, «Art, as the word, results at a time, from a symbolic exchange and a concrete practice. It implies the simultaneous production of a sense and of a physical presence.» (Allan Sekula, Écrits sur la photographie, p. 143). In order to fight the material inequalities brought by advanced capitalism, from one side and to delegitimate the alienation provoked by the automatisation of work and the massive consumerism, from the other side, to Sekula, it is urgent to rethink the theory of art. Starting from the history of photography.

At the beginning of what is unanimously considered his manifesto, Sekula claims: «How do you take the photography against the grain? By authorizing the alternate coexistence of the roles of the ‘critic’ who thinks and writes on photography and the ‘visual artist’ who takes or uses photographs, so difficult this could be.» (Allan Sekula, Écrits sur la photographie, p. 51). To do that, Sekula suggests to consider a social and materialistic history of photography. By mentioning Benjamin's famous quote from his thesis On the concept of history (1942), «there is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism», Sekula argues that photography needs to be considered in relation to its economic and technological determinations. If any work of art isn't freely accessible in every historical period, it means that culture can't be reificated, by being reduced to a reproducible object, then consumed and transformed into a fetish product, in the absence of any authentic experience. This is why, in his philosophy of history, Benjamin found in historical materialism a way to «’take history against the grain’» (Allan Sekula, Écrits sur la photographie, p. 58). In the same way, Sekula suggests to make a critical history of photography by giving attention to the notion of ‘traffic’. «In the literal sense of the term, this traffic implies the social production, the circulation and the reception of photographs in a society founded on the production and the exchange of commodities.» (Allan Sekula, Écrits sur la photographie, p. 58). The traffic in photographs, to which Sekula dedicates an essay in 1981, means that the material dimension of art and culture must always be understood in relation to its theoretical and aesthetic meaning. Between objectivism and subjectivism, rationalism and irrationalism, positivism and metaphysics, scientism and aestheticism.

Eventually, in this meta-documentary, critical and materialistic approach, photography must still be considered as a resistance and an opposition. First of all, the identity of photography as a document would be understood in the terms of a shared experience with literature and cinema. Its meaning would always be experimental, contingent and context-dependant, rather than immanent. Being determined in avoiding «what Perry Anderson qualified as ‘megalomania of the signifier’» (Allan Sekula, Écrits sur la photographie, p. 53), the photographer would always be considered as a social actor, whose vision is never objective yet always, we could say, critically realistic. Thus, what remains in an era of advanced capitalism is the temporal dimension of the photograph. If the camera too often kills the lived time, then, in order to find the humanity, maybe we should look into the intervals of socially committed photography, where freedom still resists.

Bibliography

BEAUSSE, Pascal. (1998). «The critical realism of Allan Sekula». Art Press. N.° 240 (Nov.), p. 20-26.

BENJAMIN, Walter. (2008). The work of art in the age of its technological reproducibility. Cambridge, Massachusetts - London, England: Harvard University Press.

–. (2003). Essais sur Brecht. Paris: La Fabrique.

BRECHT, Bertolt. (2000). Écrits sur le théâtre. Paris: Gallimard.

SEKULA, Allan. (2003). Performance under working conditions. Vienna: Generali Foundation.

–. (2013). Écrits sur la photographie. Paris: Beaux-Arts.