r

e

v

e

s

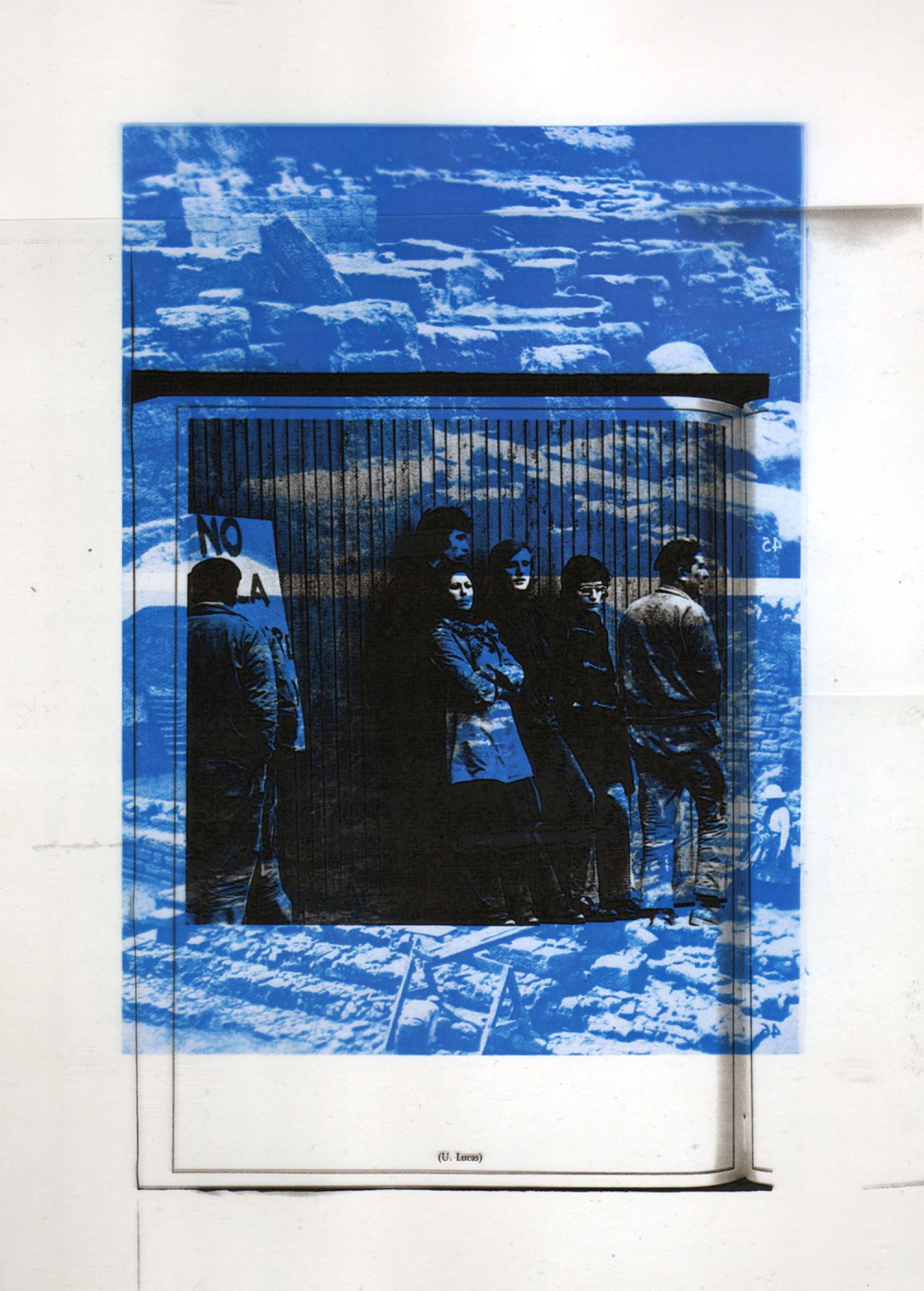

Os registos da transformação das cidades enquanto objecto encontrado.

O que sobrevive do urbanismo, das aspirações subjectivas e políticas sobre um território. O que podemos ler quando escavamos a sua história. Que motivações e ideias encontramos ao estudar os seus estratos diacrónicos. Essas ideias são também artefactos; como reutilizá-las, reintegrando a experiência dessas práticas, daquilo que nelas é fundador e perene, e daquilo que constitui a sua falha e omissão.

Old Forms of Future Events foi iniciado em 2009, com uma apresentação sob o modelo de uma conferência/performance na exposição «World Question Centre» com a curadoria de Chus Martínez, inserida na Bienal de Atenas. O projecto assume agora uma via exploratória enquanto material para uma pseudo-ópera que fala da transformação do território.

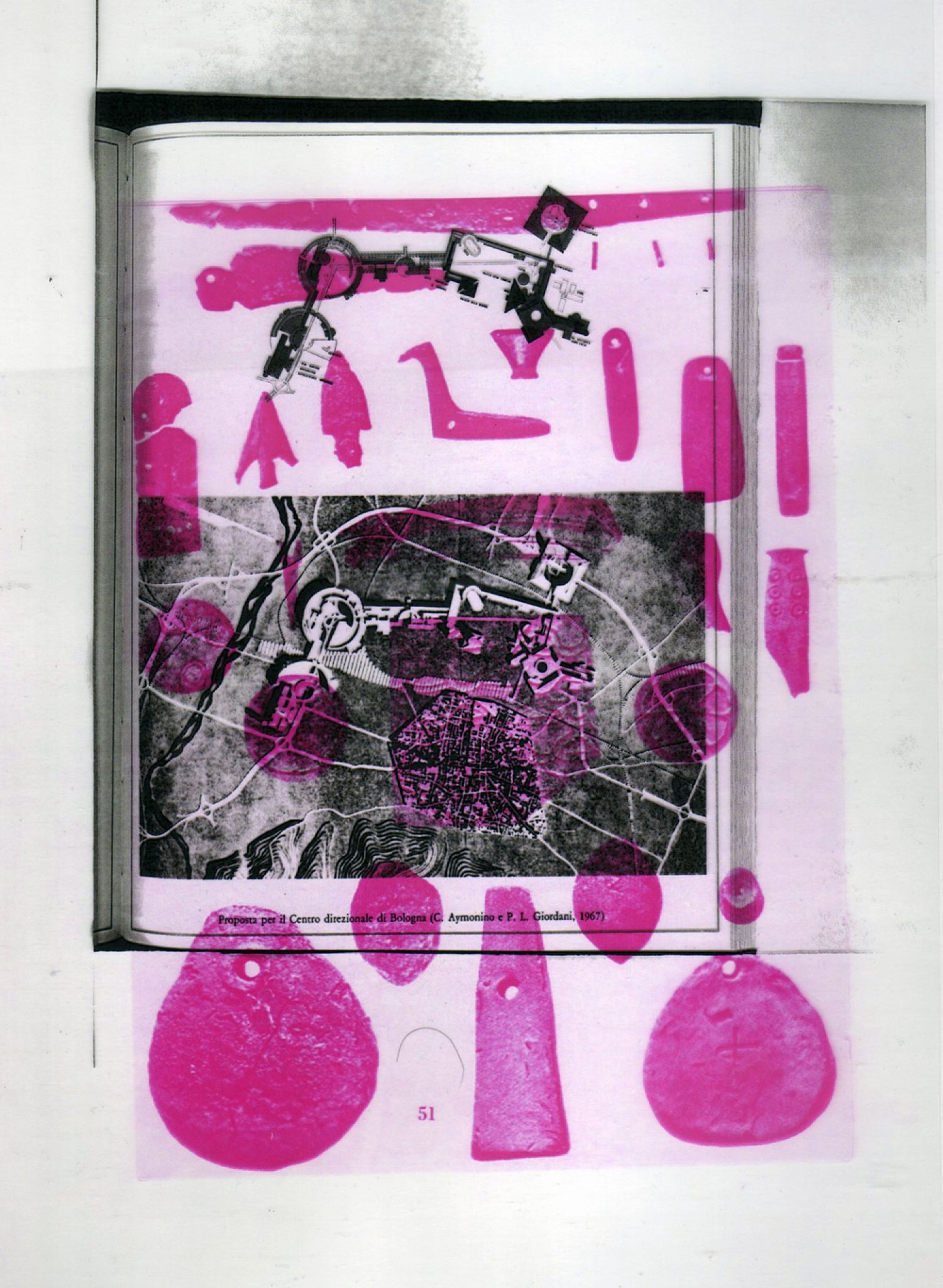

O desenvolvimento de Tróia e das cidades italianas na segunda metade do séc. XX surgem neste projecto como objectos de livre-associação para conduzir esta reflexão, sinapse improvável entre a antiguidade e a época contemporânea. Nos esboços de diálogos aqui apresentados, e que farão parte do possível libretto, cruzam-se um arqueólogo (Carl W. Blegen) e um urbanista (Marcello Fabbri), entre vários outros agentes que participam na discussão sobre a cidade que teve – ou não – lugar. E da cidade que há-de vir.

The «great dimension»

(…)

The archeologist: [The archaeological Troy – the Troy that was built by masons, carpenters and labourers, of rough stones or squared building blocks, and crude bricks made with straw, of wooden timbers and beams, of clay and probably thatch for the roofing — that Troy, in its ruined state today, differs greatly, so far as its appearance is concerned, from the glamorous citadel pictured in the epic poems.]

A citizen: During the reconstruction after the Second World War funded by American aid and the Marshall Plan, the Italian economy underwent a profound change.

Chorus: The traditional Italian protectionist closure was quickly overcome!

A citizen: Mainly because the dynamic forces of the Italian capital that found alliances internationally. It was the big opportunity for them to enter the world market…

The archeologist: [If one is blessed with a little imagination, when one stands on the ancient hill top in the extreme north-western corner of Asia Minor and looks out over the Trojan plain and thinks of some of the many exciting scenes it has witnessed, one cannot escape feeling that this Troy, too, has a powerful touch of enchantment.]

The urbanist: We’re here today to talk about a process that had significant consequences in the territory…

Chorus: How can we look today to all that was unachieved in urban planning?

The urbanist: If we want to speak about the defeat of the town planners we must discuss the urbanization process that broke out in Italy during the 1950’s.

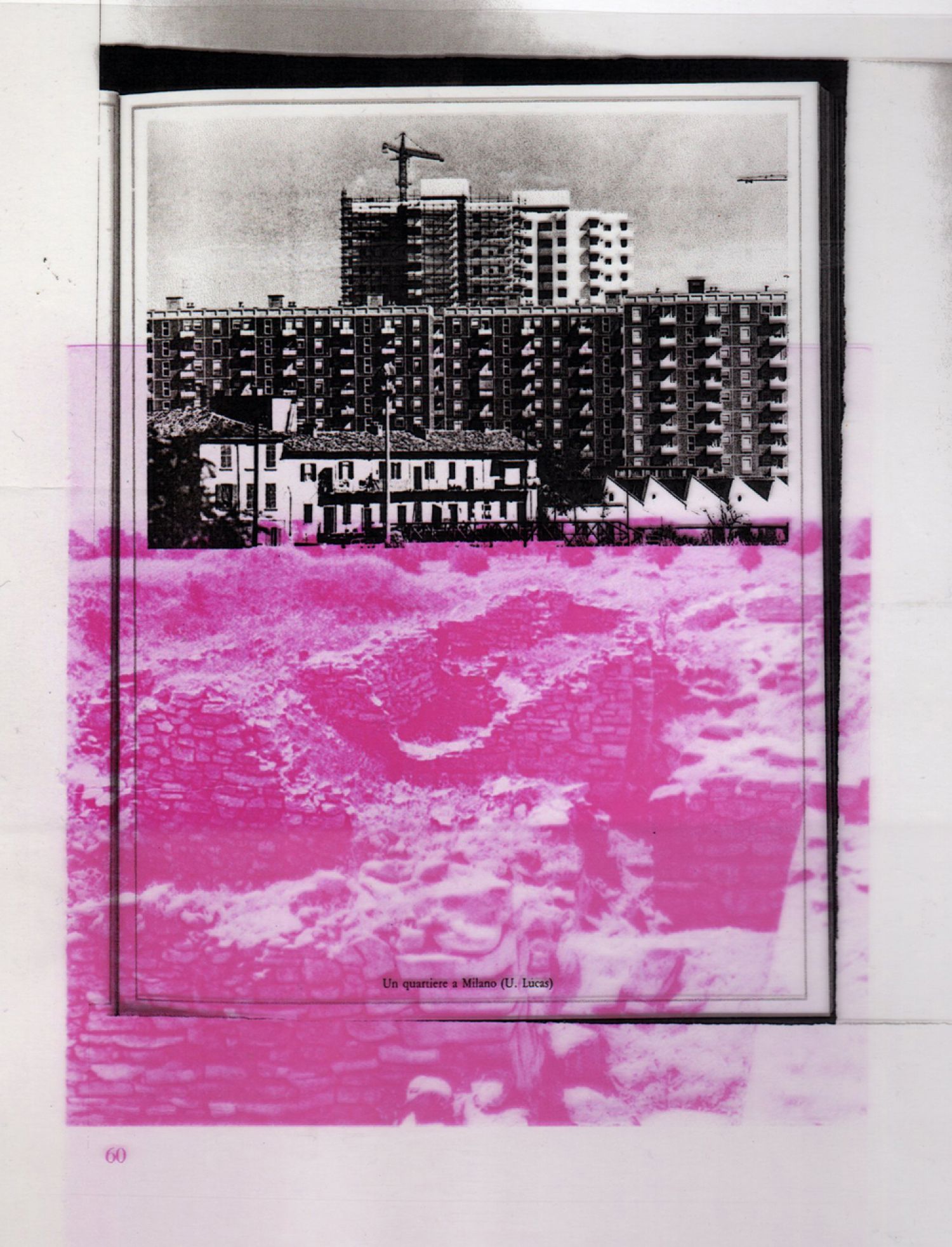

The political scientist: The local administrations became even more corrupt and the construction laws were ignored while the number of buildings built with poor materials increased for speculative reasons. The prices skyrocketed: between 1953 and 1963 the amount of new buildings tripled, while the average cost of building land was ten times greater; the major increase was registered during the second half of the decade. This meant that the cost of the areas affected more and more the total cost of the buildings.

The urbanist: The increase of the cost of buildings decreased due to the fact that most of the labour in this field of production was lacking of qualifications, in fact the building industry was the area most capable of absorbing workers coming from the countryside and generally paid with low salaries.

The political scientist: Naturally, the building boom had its effects on the lands already occupied and the buildings, with a proportional raise of prices…

The archeologist: [The ruins we see, called Hissarlik, occupy the western tip of a low ridge coming from the east and ending somewhat abruptly in steep slopes on the north and west and a more gradual descent toward the south.]

Chorus: There were great expectations on the role of «culture» to mitigate these disasters.

The urbanist: The urbanists, as prophets unarmed, were in a position to engage in Italian affairs, only as they could establish a relationship with the power structures.

The archeologist: [Some four miles distant to the westward, across the flat plain of the tree-bordered Scamander, and beyond a line of low hills, is the Aegean Sea. On it, to the southwest, floats the island of Tenedos — which was sacked by Achilles — and much farther northward is Imbros, where, the sorrowing Hecuba says, some of her sons who had been captured by Achilles were sold into slavery. Behind Imbros, on a clear day, one sees the twin peaked height of Samothrace, and often when the weather is at its clearest, one can even make out the summit of Mount Athos.]

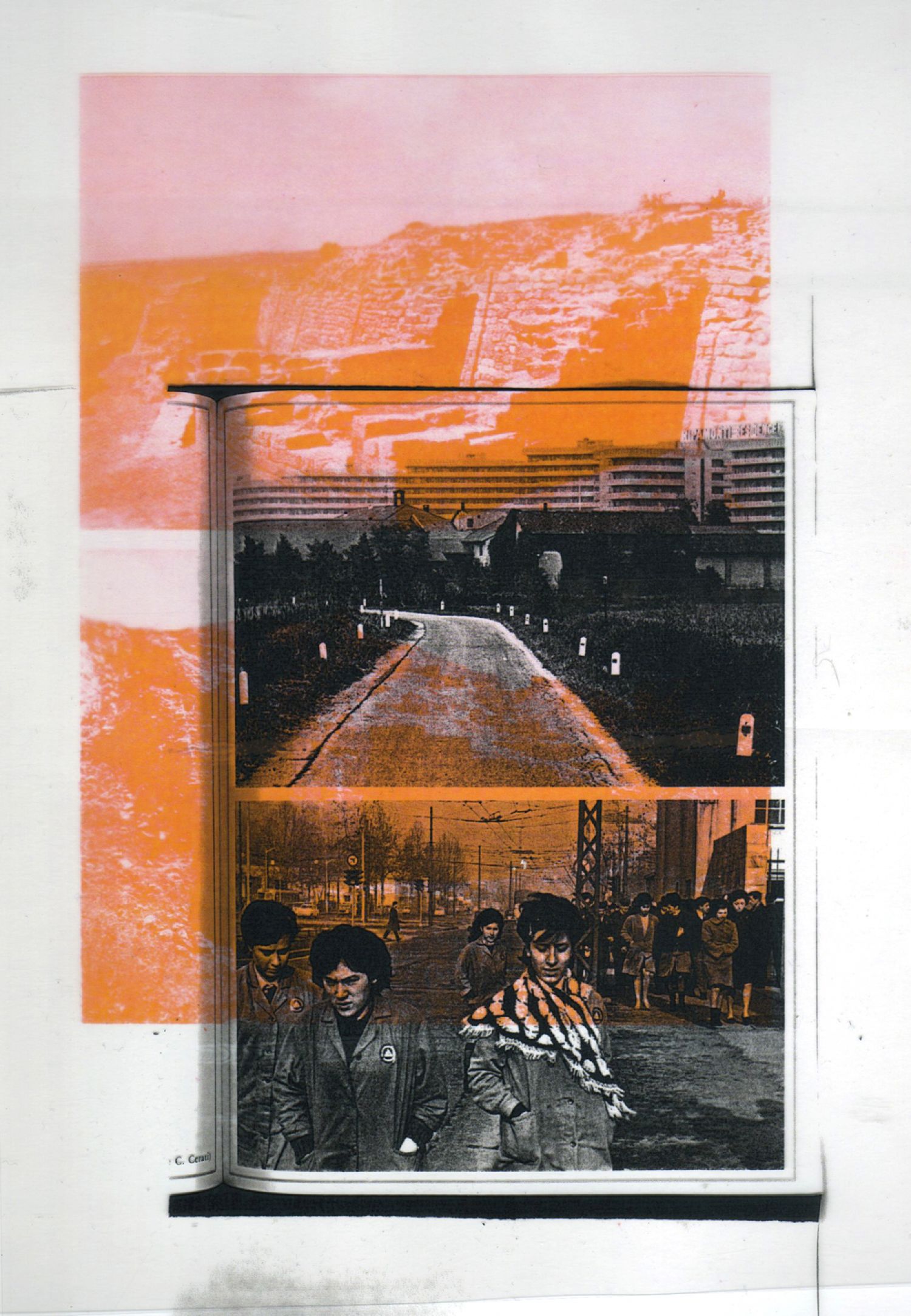

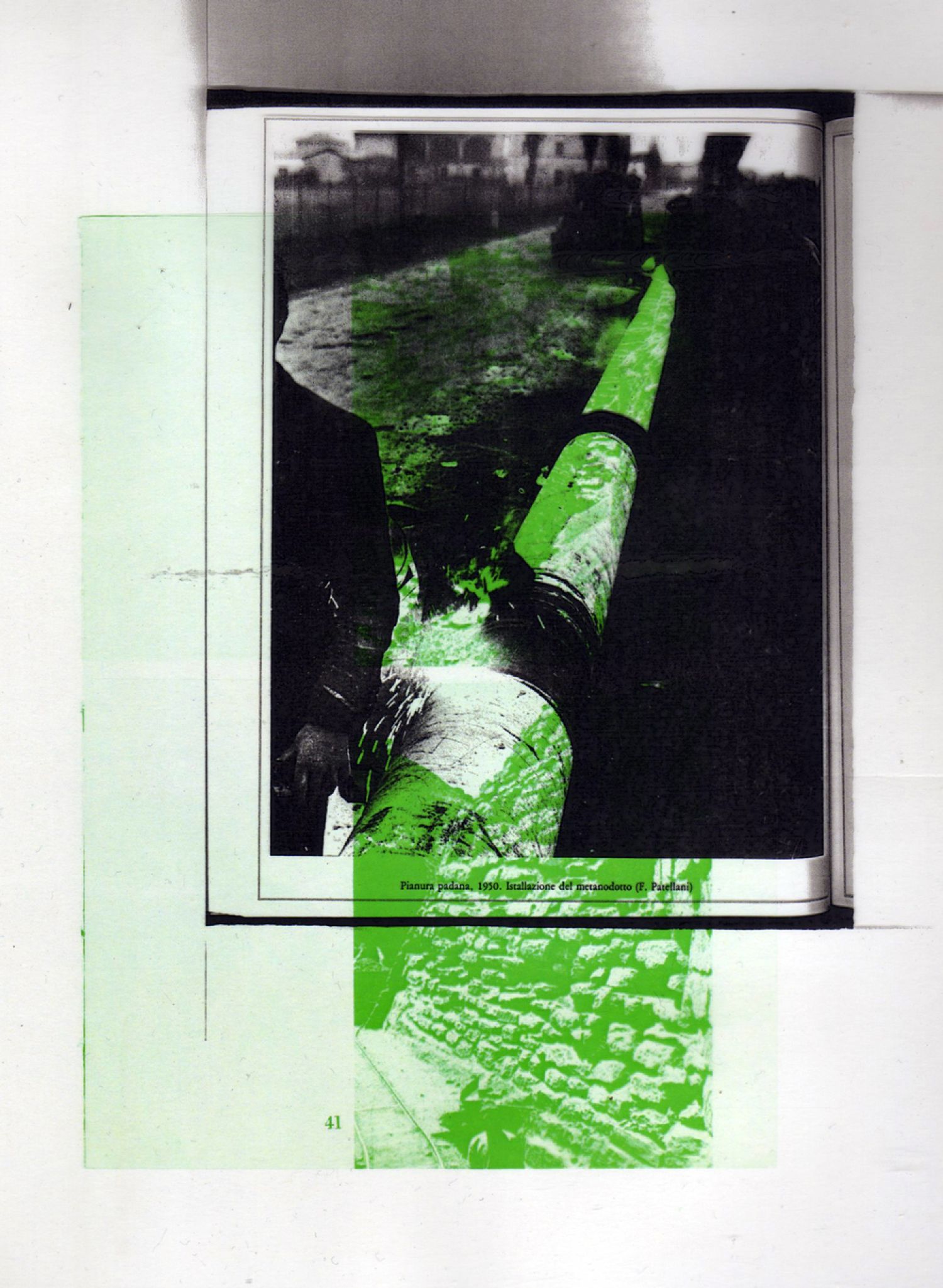

A citizen: The old preindustrial and underdeveloped Italy was transforming according to new parameters and dimensions: left behind the past, masses of people were relocating in the country and the cities were generating new urban areas.

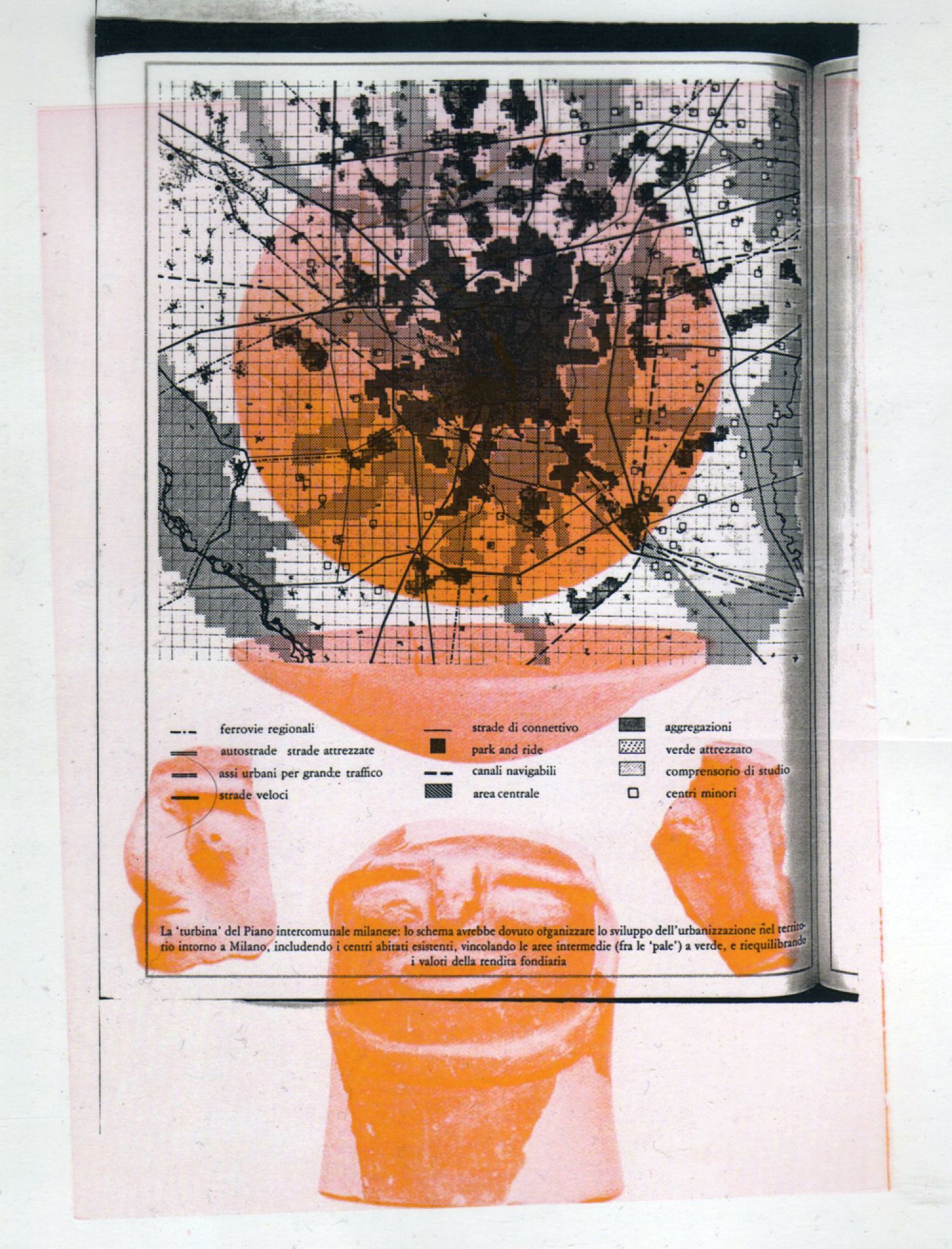

Chorus: Le aree metropolitane.

The urbanist: A public enterprise together with the large associated corporations started a plan of a motorway. The new road layouts were inserted on a totally autonomous scale and dimension, bringing forth the habit of viewing the «landscape» in quite a different way respect to the pre-motorway era, as a fictitious scene elapsing in a way similar to the fast cinema or television sequences.

Chorus: La Tv incominciava appunto a diffondersi in quegli anni.

The urbanist: Nature became artificial, while the urbanized and constructed landscapes acquired a certain naturalness made up of long asphalted lines, service stations and motels, the departure and arrival barriers, and the large expanding urban suburbs.

Chorus: Oh, la voglia di fare le cose grande…

The urbanist: Yes, the desire to «do things on a large scale» started to spread under the power of a consumer civilization and in the background of a «discipline» that was aimed at organizing the consumer function precisely.

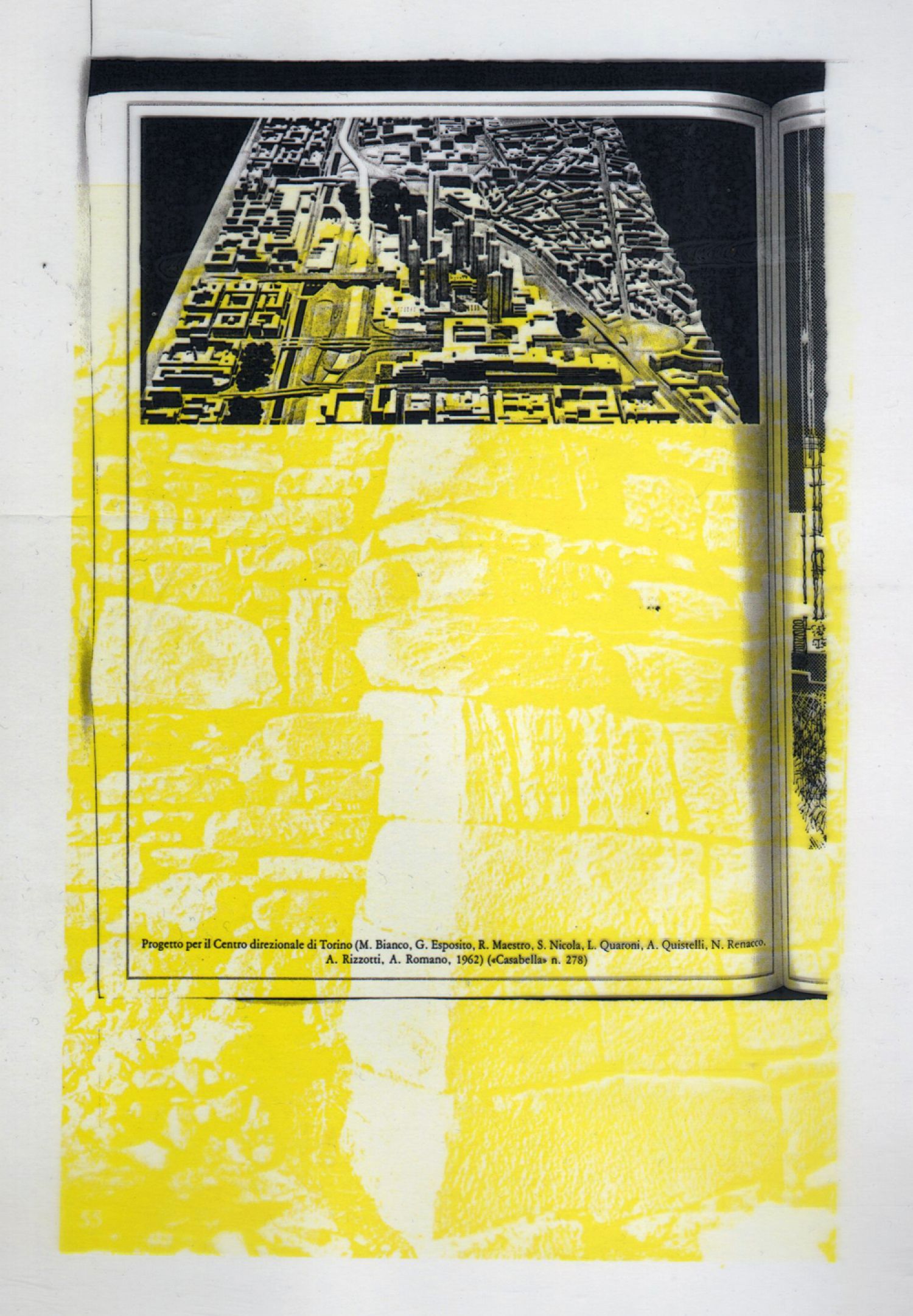

The designer: The first signs of merchandise fetishism were noticed in the magazine Casabella with Argan’s theorizations about design starting from an old aspiration of the modern movement to exert an «artistic control» over the production processes. Due to the choice of private consumption, design offered to transform daily life with a mission of civilized refinement and introduction in the urban and industrial «culture».

The art historian: In fact, the design must establish a relationship between the consumer and the merchandise, capable of replacing the relationship in pre-industrial civilization between people and objects. It is a process analogous to the transformation of the landscape from natural to artificial through the fruition of it along the great works of urbanization on a territorial scale, as the highways.

The designer: But this design has to be able to trace, to have its own historical motivation; it is not a costume tradition, but the principle of a technique, the process of a creativity that emanates from the whole sphere of society and society is radiantly irradiated. Therefore, the variety of species is explained in the design method unit. And its passage from the form of domestic furnishings to the shape of the city and the region; and its need to identify itself in urban planning, understood as a continuous planning of life and social progress.

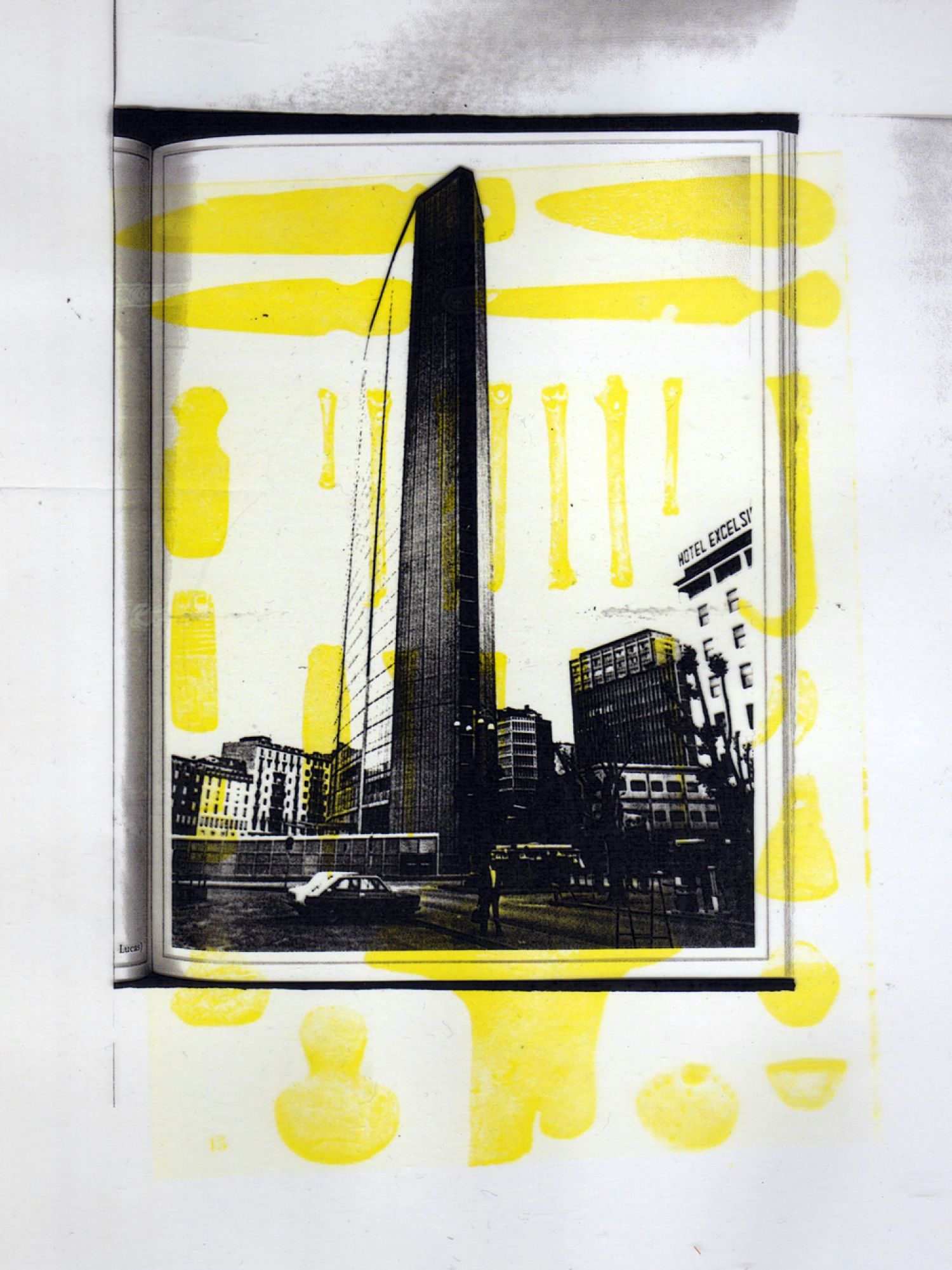

Chorus: It is the time of the Torre Velasca, the Pirelli skyscraper… and all the urban works of «great dimensions» in the financial district of Milan.

The urbanist: The phenomenon was a sign of a change of times: the revision of the modern movement was not anymore addressed towards a populist realism, but instead inspired by the discreet charm of the bourgeoisie showing us through which mediations the continuity from design to city planning passed through the phenomenological fashion.

Chorus: The economic boom has allowed a much higher number of Italians than before to live an affluent lifestyle, but always remaining a minority. About 25 percent of the population reached a decent level of life according western European models, but the majority remained well below this level and a considerable part still lived at the limits of sustenance.

The archeologist: [Looking on all this one remembers the story told by Aischylos of the fire-signals that flashed from peak to peak across the sea and land to Mycenae, announcing to Climnestra the news that Troy had been captured.]

(…)

Urbanistica Opulenta

(…)

The archeologist: [The mound of Hissarlik had a maximum length of some 200 m. and was less than 150 m. wide. It rose approximately 31.20 m. above the level of the plain at its northern foot, the summit, composed of debris of human habitation, reaching an elevation of about 38.5o m. above sea/level.]

Chorus: Rationalization and efficiency were nothing but ideals.

The urbanist: Ideals ill-adjusted to the real subject of the issues involved in Italian society and, therefore, at the same time, compared to that of its own theoretical practise, a whole sector emerged with urban planning proposals and debates of those years surrounding the formal organization of those ideals in space.

A citizen: The critical dissatisfaction for instruments drawn up in the wake of Modernism does not go beyond the logic in which the Modern movement was immersed. All the efforts of the debate of those years seemed designed primarily to identifying this way out, without finding it.

Chorus: Ideology and architecture are intertwined.

The archeologist: [For an administrative centre and a capital the situation was admirably suited, both for security and for economic reasons. It lay near enough to the sea to have landing places and perhaps a small port or two within easy reach, and yet far enough away to be reasonably safe from sudden hostile attacks or piratical raids. It also controlled a land route that apparently came up along the western coastal region of Asia Minor to the shortest crossing of the straits from Asia to Europe. From its vantage grounds it could no doubt likewise dominate traffic up and down the straits, and perhaps tolls of some kind were exacted from those who passed.]

The architecture historian: The Modern movement was born as a conscious attempt to transform the world through design, beyond particular lines of figurative development, and this ideological trait is the unifying moment. Today we are clearly living in a neo-capitalist universe in which the inherent contradictions of the system tend be magnified and this new undeniable reality continuously offers the architects new flattery…

A citizen: And by accepting them, most architects self-confirmed themselves in the imaginary roles of actual planners, unable to recognize back then a real new generation driving the Italian and also international reality.

Chorus: Architects became urban planners.

The architecture historian: It is a dangerous illusion that limits, when it does not simply coincide with technocracy and superficiality. I ask up to what point does utopia not represent an evasion? Or instead, up to what point is the road of a positive utopia not really fertile in a world that is too linked to contingencies and to case by case... The research and project does not leave the sphere of figurative proposals, resulting into a wish of willingness to adapt to change.

A citizen: Town planning seems often just a collocation of forms in the city – great containers, business centres, images of great infrastructures. They all crystallize the State – the public power. Production and management mode are separate from the society. They’re an image – a container – to fill with contents intended produce certain effects on that «civil society»...

Chorus: A theoretical rationalisation that eroded the private imagination for the reduction of conflicts to efficiency, aesthetics and public order.

The urbanist: It was an idealistic and theoretical vice eliminating from urban planning the element of conflictuality of these ideas with the «civil society». Projects were applied to a non-reality and removed every operational value from the effort of imagination, which are obviously always self-consuming and self-thinking.

The archeologist: [Few comparable ancient sites have been so extensively and so searchingly excavated as Hissarlik.]

(…)

The «Quaderni rossi»

(…)

A citizen: In the early sixties, amidst the radical changes in the Italian tumultuous and contradictory economy and society, a new generation of students was encouraged to analyse the characteristics and the historical itinerary of the processes under way in urban planning, in an attempt to identify possible outcomes for a situation that add sometimes tragic imbalances…

Chorus: – such as the great migration and the rural exodus –

A citizen: And also some inconsistencies.

Chorus: – such as the contrast between economic expansion and the backwardness of political and administrative solutions.

The urbanist: A new group with a critical attitude towards left-wing culture and politics that circled around the Italian politician, writer and Marxist theoretician Raniero Panzieri.

Chorus: … the founder of Operaismo.

The urbanist: He started the publication from 1962 of the Quaderni Rossi. The magazine immediately this magazine attracted «generational» attention. Although it had a decisive influence on culture and on the attitudes of the left-wing and trade unions in 1968-69, its influence was more deeper and had more lasting effects on a «diffuse culture»…

A citizen: … on a collective imagination which engaged with new cultural choices that were no longer provincial and the taste of discovery and renewal of the critical method.

The archeologist: [As Heinrich Schliemann proceeded in the excavation, he began to notice that the debris did not form a single homogeneous mass but had grown up by gradual accumulation in numerous superposed layers, one above the other, and evidently representing a like number of chronological stages or periods. In due course, Schliemann was able to distinguish at least seven, and ultimately, with Dorpfeld’s aid, nine, main layers extending through the mound.]

The urbanist: From inside the working class’ struggle against the capitalism system, the Quaderni Rossi questioned, in real terms, the issue of the partly new conditions in which new avant-garde groups operate – and among these the Quaderni Rossi – called to take on more rigorous responsibilities in political interventions.

The archeologist: [Schliemann called them «cities»: First City, Second City, Third City, and so on, counting from the bottom upwards. Seeing that the lowest layer, Troy I, produced for the most part only rude stone and bone implements, primitive pottery, and very little metal —chiefly copper — he concluded that he had erred in thinking the First City to be the Troy of Homer, and he shifted his identification to a thick burned layer which he counted as the third from the bottom. In this deposit he discerned remains of a much higher culture, finding many «treasures» of gold, silver, and copper or bronze, including one splendid hoard of royal weapons, vessels, and ornaments. In 1882 a further revision was made when Dorpfeld pointed out to Schliemann that the «Burnt City» actually represented what must have been the final phase of Troy II.]

A citizen: Yet, if this and other publications were addressing the relation between theoretical elaboration and intervention, there was still a problem … It is an illusion to think that it was just necessary to provide «theory» to the «class» in order to find the weapon necessary and sufficient to lead its political fight…

Chorus: Indeed. In terms of putting theory into practice, town planning, as a discipline in the relationship between production and society, and the knot of their relationship, suffered the consequences due to the State’s general lack of theory and practice.

The archeologist: [Some years later, in 1890, Schliemann and Dorpfeld together discovered that yet another modification was necessary; for near the southern border of the mound, far out, side the fortification walls of Troy II, they came upon a large building similar in plan to the throne-hall in the palaces at Mycenae and Tiryns; it was clearly associated with a deposit of Troy VI which contained a good many fragments of Mycenaean pottery of the types that were well known to the two excavators from their explorations at Mycenae and Tiryns. This was a startling blow to Schliemann.]

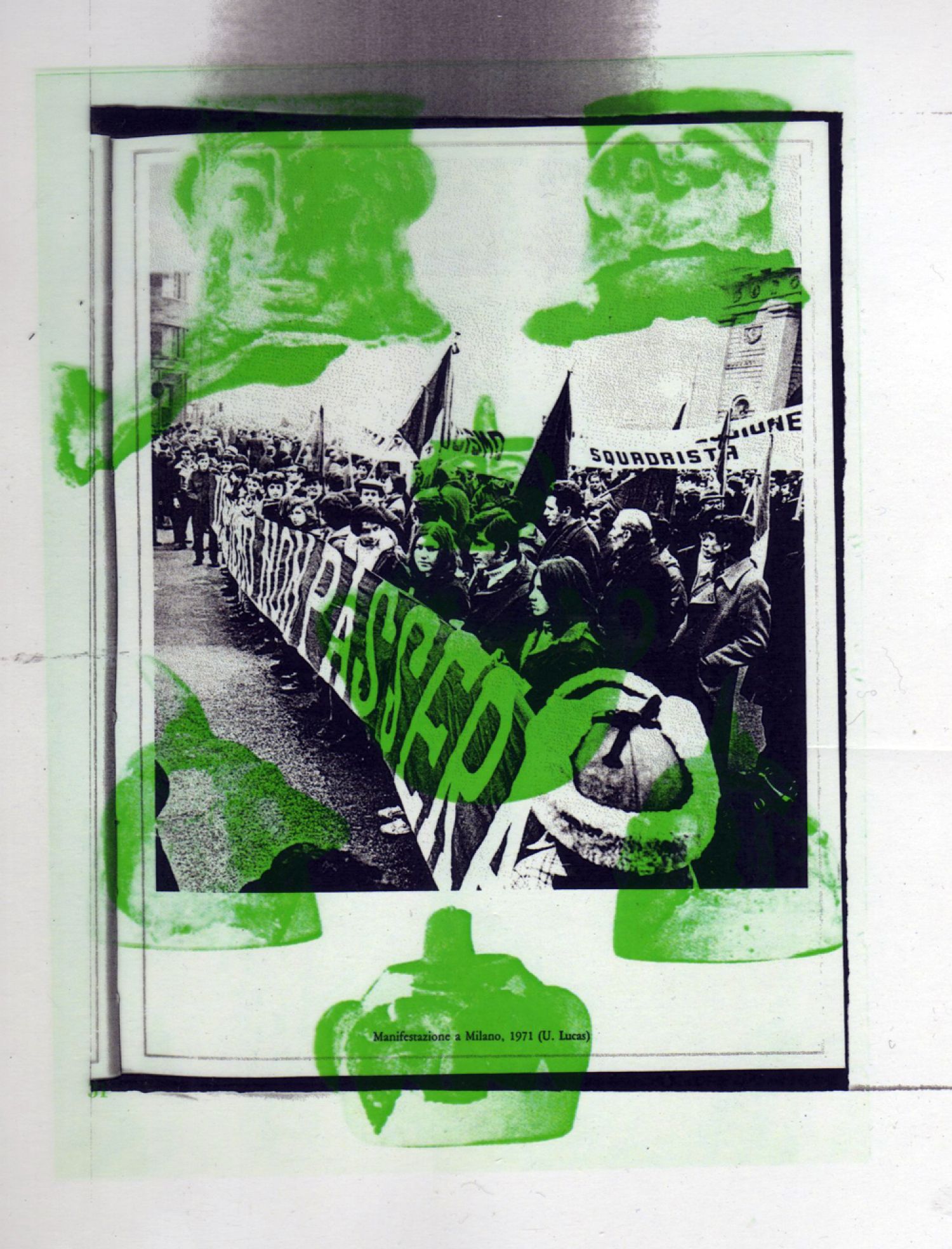

The urbanist: The student mobilisation was a motivational force of the workers’ struggles, up to when a more correct outline of the connection was reached as a support for autonomous struggles: the work was concentrated mainly on the building sites, by promoting the creation of on-site newspapers written by the workers in view of the forming of autonomous executives.

Chorus: To know and transform a reality it is necessary to participate in it.

A citizen: The work by the students on the building site was not sufficient. An intervention had to be made where the builders lived, in the surrounding burghs and towns of the commuting building workers, where they created quarter committees. So many to them started working in schools and in the community’s schools. They wanted to start a process of knowledge «from within»; departing from an «inquiry» work up to the political fight.

Chorus: «The student-militant, in the building sites and suburbs will be able to know-participate the level of life and discomfort of the masses!»

The urbanist: In many Italian cities by early 1970s it seemed that these youth groups could actually be a form and force that could help determine a town planning policy. The students «movement» was about investing on the reappropriation of the city by autonomous and spontaneous «base» organizations, managed to have an effect on the institutional form through the urban issue, addressed from the side of the dwelling place, the daily life. Departing from a theoretical interest towards the problems within the organisation of production, with a progressive shift towards the «social», it affected some aspects of the State’s structure –

Chorus: – without having substantially amended production…

A citizen: These spontaneous initiatives seemed to be symptoms. The disruptive action of the forces breaking up the established functioning of «urban society», a top-down dismantling of the existing society.

The urbanist: … but questioning nevertheless the rigidity of centralised power.

A citizen: It was a movement of transition…

Chorus: La cultura della transizione.

The urbanist: The continuous proliferation from 1968 onwards, with varying degrees of success, of spontaneously formed groups above all aimed at managing urban struggles, or of factory committees, district councils or other forms of decentralised initiatives, continuously fuelled «urban conflict», via social practices which brought a new force to Italian society. This tendency of the Italians to associate had not been witnessed since 1944-45…

A citizen: Like the students’ groups, many other groups started to correspond to a new process of restructuring from the bottom up.

The urbanist: The foundations and starting points were to be found in city district life, club life, and lastly the general desire for action and struggle which cements the existence of the community, in the very disintegration of habitual forms and structures.

The archeologist: [Without written documents, in an event, the only source of in information available in an attempt to reconstruct the history and manner of life of the Trojan people is the material brought to light by the excavations, the ruins of the walls and buildings of the successive settlements, and all the various and sundry objects recovered from the sequence of layers in the debris. Difficulties present themselves here, too; for exact records from the early campaigns, when most of the digging was done, are scanty and incomplete.]

(…)