r

e

v

e

s

«At school, I remember white children sat in the front of the classroom, while the Black children sat in the back. We from the back were asked to write with the same words as those in the front – «because we are all equal», the teacher said. We were asked to read about the «Portuguese Discovery Epoch», even though we do not remember being discovered. We were asked to write about the great legacy of colonization, even though we could only remember robbery and humiliation. And we were asked not to inquire about our African heroes, for they were terrorists and rebels. What a better way to colonize than to teach the colonized to speak and write from the perspective of the colonizer.» – Grada Kilomba, Plantation Memories: Episodes of Everyday Racism, 2013, p. 34

In the Portuguese historical lexicon the term «discovery» stands not only for «the action or process of discovering or being discovered for the first time» (OED): «discoveries», in the plural, is also the term given to the imperialist project undertaken by Portugal for more than 500 years, from the invasion of Northern Africa in the 15th century to the handover of Macao to mainland China in 1999. It is not clear when the term «discoveries» was first used in the latter context but its implication in the reading of the Portuguese imperialist project should not be overlooked. Intentionally obscuring the atrocities and violence of the colonial project, «discoveries» conveys colonialism and imperialism as an inaugural, well-intentioned and quasi-friendly encounter with the so-called «new world».[1]

This paper focuses on the contemporary currency of the term «discoveries». It looks into the most recent museological projects dedicated to this historical period and the relations of these museums to the celebration of the imperialist past under the contemporary conditions of neoliberalism (i.e. the touristification of culture) and the economic and social crisis in Portugal since 2008. This analysis – more than being a museological study of the exhibitions’ histories and displays, or a rewriting of the colonial history – is intended to draw lines between contemporary museological practices, visual cultures and the politics of exhibition. It aims to read the rebranding of the imperialist narrative phenomena as a fetish for the lost empire that finds its uncritical arena in the touristification of the narrative of «discoveries».

This analysis draws on two main phenomena: infrastructural and discursive. Infrastructural phenomena include the «discoveries» museums, which were built in the last eight years in Portugal, such as the Museum of the Discoveries in Belmonte – with a focus on the colonisation of Brazil and its first coloniser, Pedro Álvares Cabral; the Wax Museum of the Discoveries in Lagos; and the World of Discoveries in Porto. The museum in Belmonte first opened in 2009, followed by the other two in 2014.

This physical infrastructure does not manifest itself without a larger discursive context. For this reason, it is important to mention discursive manifestations in the «public sphere» (Habermas, 1989), which are necessarily embedded in everyday discussions and assumptions. In the last seven years, a new museological project similar to those mentioned previously has been announced a number of times in Lisbon, but never realised. The first announcement occurred in 2010 when Gabriela Canavilhas was Minister of Culture. She pledged that the new museum would be housed within the Jerónimos Monastery in Lisbon. The Monastery was built in the 16th century to celebrate Portugal’s imperial incursions during the reign of Manuel I (1469–1521). Its architecture is marked by naval and maritime symbols and is named after the King, hence manuelino. The connection between the site and the proposed museum shows the intention to bring to the fore a celebration of the heydays of the Portuguese empire – rather than a critique – by placing it within a structure that itself performs an act of homage to the empire. Second, and more recently, Lisbon’s municipality announced the planning of yet another «discoveries» museum as part of a regeneration plan to be undertaken using the profits from increased tourism in the city (Boaventura, 2016).

On the Museum’s Function

The birth of the museum as a public institution dates back to the beginning of the 19th century, but it is worth looking into its original functions in order to understand contemporary politics of display. Eilean Hooper-Greenhill argues that the ruptures of the French Revolution «created the conditions of emergence for a new ‘truth’, a new rationality, out of which came a new functionality for a new institution, the public museum» (1989, p. 63). Established as means of making available to the public what had previously been private and concealed, such as collections of artworks and artefacts owned by aristocratic families or monarchs, the public museum «exposed both the decadence and tyranny of the old forms of control, the ancient regime, and the democracy and utility of the new, the Republic» (Op. cit., p. 68).

The museum was proclaimed as an instrument to serve the collective good of the state – to educate the masses in culture and history, through the exposure of objects previously held within the four walls of the elite's domestic spaces. In this way, the museum was also formed into an apparatus with three deeply contradictory functions: «that, of the elite temple of the arts, that of a utilitarian instrument for democratic education» (Op. cit., p. 63) and, most importantly for my argument, as an instrument of the disciplinary society – as described by Foucault (1991).

In the museum the apparatus of visuality – in other words, seeing and being seen – helped to shape the new citizen of the new disciplinary society where bodies were under surveillance within a public institution. This model of surveillance was no longer the previous model of governmental punishment, but rather one where citizens were exposed to each other as a means of self-regulation and control. Through this seeing and being seen in the exhibition space the conduct of the new «man» was to be rendered docile.

The notion of educating the masses also implied a separation between the producers and the consumers of knowledge. The organised display of objects and peoples – which in the exhibition space operated as systems of representation that produced meaning – were elaborated by those equipped with scientific knowledge. Displays operated as language, as ways to convey meaning through exhibition and its interpretation. They did so through legitimised disciplines – say, scientific – related to the shows and collections. For instance, this would be the case for biology in the context of natural science museums, anthropology for the ethnographic museums, and so on.

According to Henrietta Lidchi (2013), scientific knowledge and the birth of the museum are intrinsically connected to the expansion of Western nations – namely, the European colonial project. These «exhibitionary» projects were used to convey Western ideology, which was based on Western superiority, racial hegemony, and the culturization of the Other. Not only was this manifest in museums but also through international colonial exhibitions, as argued by Tony Bennett (1995).

International exhibitions became famous in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In contrast with museums’ permanent exhibitions, temporary shows could respond more efficiently to immediate political agendas. The most remarkable Portuguese example was the Exhibition of the Portuguese World, in 1940, which celebrated the anniversary of the country's foundation. On a political level this exhibition was for António de Oliveira Salazar, the dictator of the time, a way to put together a multi-dimensional example of his imperialist and racist ideology (Acciaiuoli, 1998).

Held on the banks of the Tagus River near the Jeróminos Monastery, the exhibition was meant to stress, in particular via its symbolic location, the maritime incursions and grandiose narrative around the Portuguese empire’s «great deeds». Even today some remnants of the show can still be seen, such as the Padrão dos Descobrimentos (Monument to the Discoveries) created by Cottinelli Telmo (1897–1948) and the sculptor Leopoldo de Almeida (1898–1975) (França, 2004). In order to understand the current politics surrounding the display of this monument, after more than eighty years of exposure, we need to go beyond the temporality and the space of display of the exhibition. In other words, how do we understand the broader field of exhibitionary technologies beyond the temporality and the space of the museum? And, in the specific case of the Monument to the Discoveries, how can we actualise ideas around the exhibition that are not solely based on exhibition-making?

An Expanded Field of Exhibition-Making

To think of an «exhibition» as an historical and situated event allows for an understanding of the term «exhibition» as more than a set of objects on display and its accessibility to the public. An «exhibition» is also the institutional mechanisms that govern display and knowledge production. Showing is never only about what is made visible but also about what is made invisible via the means of visibility. Following this line of thought, an exhibition is not only what is exhibited but the immanent network of power structures and degrees of intensity that govern visibility, which are inscribed beyond the exhibition space.

Understanding an exhibition as an immanent network in the broader field of cultural production allows us to read exhibitionary practice beyond the museum. Exhibitionary practice is a politics of the technologies of display that governs the concept of giving-something-to-be-seen, which is entrenched in any form of popular culture, official narratives, media and, of most importance for the argument here, the current touristification of culture.

A quick search online for Lisbon and its wonders leads us to the Go Lisbon website that offers a «top 10» list of Lisbon tours, where the number one tour is an opportunity to «travel back to a golden age» (Go Lisbon, n.d.). Although this refers back to Portuguese colonial times the perhaps surprising truth is that tourists, in today’s Portugal, do not need to have much of an imagination or knowledge about Portugal’s «golden age» because representations thereof are «set in stone» and just a stone’s throw from one another. The venues highlighted in the tour are: the Monument to the Discoveries, Empire Square, the Belem Tower, the Jerónimos Monastery, the Maritime Museum and the Orient Museum. But this is far from being the only way to discover the history of violence and atrocities that mark Portugal’s past: their remnants are ubiquitous.

In March 2014, the national newspaper Público published an infamous cover on the occasion of the Football World Cup in Brazil. The first page showed an unfortunate combination of the colonial term descoberto (discovered) and a banana. Possible readings of the image of this tropical fruit as a symbol are, arguably, multiple. But in this context it was clearly a reference to the term «Banana Republic», a popular, derogatory expression often used to refer to Latin American countries. It was coined by U.S. American writer O. Henry in his book Cabbages and Kings (1904) and came to designate a subaltern country that operated as a commercial enterprise oriented towards private profit (White, 1984). Created in the beginning of the 20th century, this phrase soon became a racist way to refer to countries of the so-called Third World (or, as they are sometimes referred to nowadays, the Global South) in a particularly economically unstable situation, marked by an economic dependence on exporting a limited-resource product.

The continuation of this imperialist and racist narrative is also evident in colloquial expressions, such as denegrir (denigrate). This derogatory term means «to speak ill of», but its etymology is «to make dark/black» or «negro». To return to the aforementioned discoveries museums, the interpretative material and texts presented in their exhibitions represent once more the continuities of the imperialist discourses. The World of Discoveries website reads:

«The Museum will have a navigable area with 12 boats with capacity for 9 adults per boat whose challenge will be to discover the world.

The historical period to which the museum is dedicated comprises the period between 1400 and 1530; in each room a theme alludes to the arrival of the Portuguese to places such as China, Japan, Indonesia, India, North of Africa and Brazil.» (n.a., n.d., my translation and emphasis)

And in the Discoveries Museum’s page on the Municipality of Belmonte’s website:

«The museum tackles the history of the discoveries as a unifying element of the new world of Pedro Álvares Cabral, the arrival in Brazil, the development and the construction of a comrade nation, their icons and Portugality.

This museum aims to show, study and communicate the great deed of Pedro Álvares Cabral; and to explore the History of the biggest Portuguese-speaking nation, which over the course of five centuries was built through the extraordinary interchange between cultures.»

(n.a., n.d., my translation and emphasis)

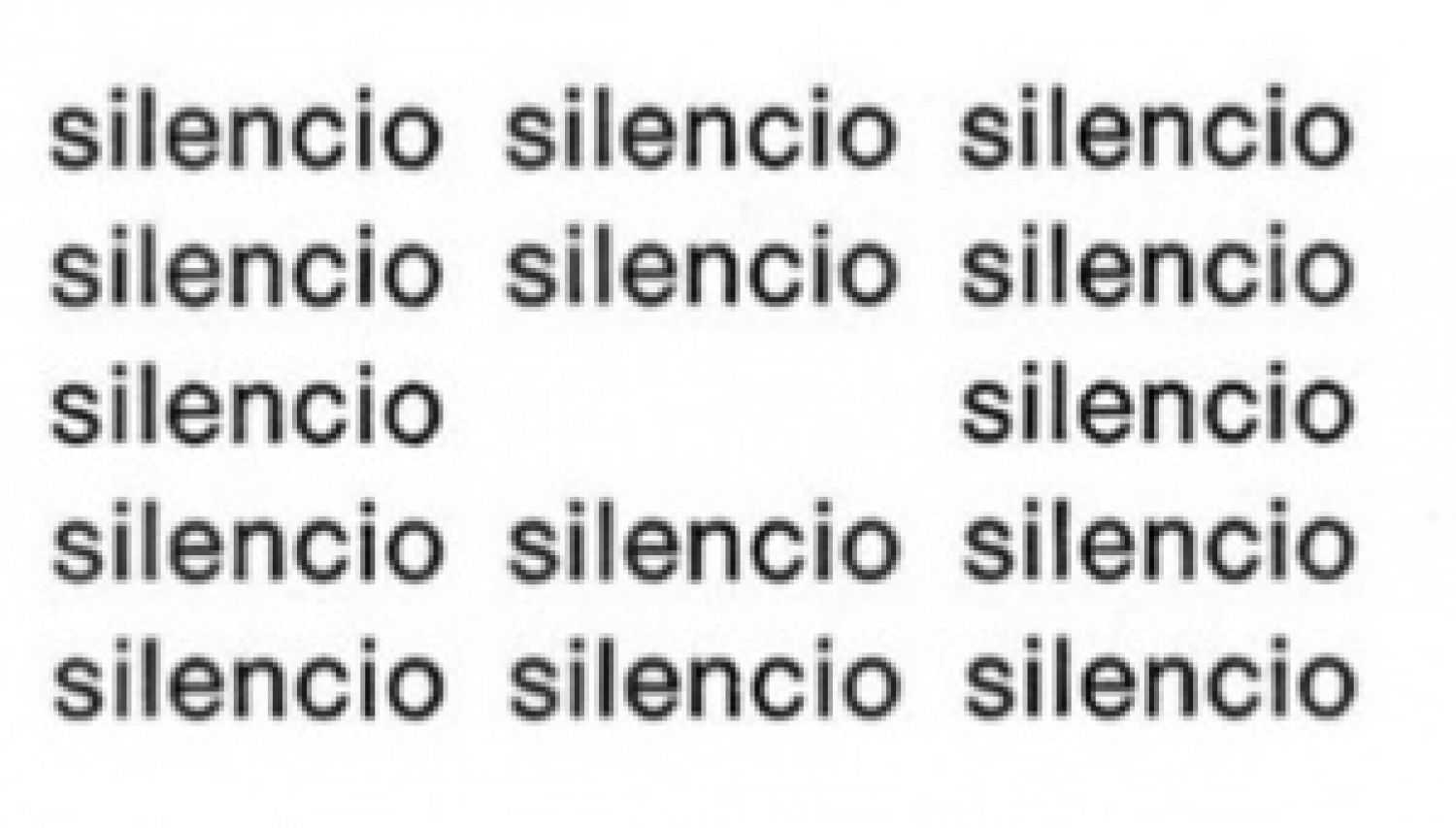

Language is also a way of making sense of this yet untold history. As Stuart Hall argues, «making sense» is not only understanding something, but producing the meaning under which things can be understood. The use of expressions like «great Portuguese explorers», «conquered lands» and «Portugal’s pioneering role in world exploration», when historicising imperialist history, stipulates intentional barriers to the understanding of the colonial project. Operating like euphemism, this uncritical terminology intends to intentionally divert a complex reading of those incursions.

Conclusion

The intentional use of diversionary vocabulary, the touristification of culture and the expanded field of exhibitionary technologies all play an important role in the uncritical rebranding of the «discoveries» narrative. Crossovers between these three axes allow us to read the phenomena within a larger political project, where the museum and exhibitionary practice are seen as technologies of governance by means of giving-something-to-be-seen.

Exhibitionary practices expand far beyond formal exhibition spaces, namely towards other modes of representation such as the media, tourism and entertainment. As the Portuguese historian Diogo Ramada Curto so rightly wrote regarding the recent controversy around the Global Lisbon exhibition at the National Museum of Ancient Art in Lisbon, the controversy should not overlook the fact that the dominant current political vision is to subsume the historical narrative (and historians) to the celebration of the Portuguese empire.[2] This is what Ramada Curto calls comemorativismo: «celebrationism» (Ramada Curto, 2017).

Such recent museological projects and debates are an attempt at political rebranding of the Portuguese imperialist project, which, within the touristification of culture, comes about uncritically as a fulfilment of longing for the lost empire. Over the last twenty years, discussions around the imperialist past were sown into a-critical soil, which has reached its peak in the contemporary post-financial crisis. Great atrocities continue to be presented as glorious and as heroic turning points in history, presenting colonised territories and peoples[3] as dispossessed from history and knowledge, sitting in a timeless path of tradition and culture (Mignolo, 2012).

This rebranding of history, more than the construction of a new narrative, is the continuation of a history that was never de-colonised, which is now being taken up under the guise of the benevolence and neutrality of the tourist economy. To conclude, this fertile and uncritical soil is only made possible by the Portuguese longing for a recuperation of the lost empire. The «trauma» of the loss of empire is imprinted throughout nationalist narratives, which occupy Portuguese literature and the arts, such as «Sebastianism» and the promise of the «Quinto Império». The triangulation of diversionary vocabulary, the touristification of culture and the expanded field of exhibitionary technologies contribute to the validation and perpetuation of colonial narratives and the whitewashing of the history of the present.

Bibliography

BOAVENTURA, Inês. (2016). «Elevador da ponte e museu dedicado aos Descobrimentos entre os beneficiários de taxa turística». Público Online. 29 September 2016. Accessed: 30 March 2017. https://www.publico.pt/2016/09/29/local/noticia/elevador-da-ponte-e-museu-dedicado-aos-descobrimentos-entre-os-beneficiarios-de-taxa-turistica-1745494

HABERMAS, Jürgen. (1989). The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: an Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society. Cambridge: Polity.

HOOPER-GREENHILL, Eilean. (1989). «The Museum in the Disciplinary Society». PEARCE, J. (ed). Museum Studies in Material Culture. Leicester: Leicester University Press.

FOUCAULT, Michel. (1991). Discipline and Punish: the Birth of the Prison. London: Penguin Books.

LIDCHI, Henrietta. (2013). «The Poetics and the Politics of Exhibiting Other Cultures». Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices. London: Sage. Milton Keynes: The Open University.

BENNETT, Tony. (1995). The Birth of the Museum: History, Theory, Politics. London and New York: Routledge.

ACCIAIUOLI, Margarida. (1998). Exposições do Estado Novo 1934–1940. Lisboa: ASA.

FRANÇA, José Augusto. (2004). História de Arte em Portugal: o Modernismo. Lisboa: Editorial Presença.

(n.d.). «Top Lisbon Experiences: #1 – Travel Back to a Golden Age». Go Lisbon. Online. Accessed: 30 March 2017.

HENRY, O. (1904). Cabbages and Kings. New York: McClure, Phillips and Co.

WHITE, Richard. (1984). The Morass: United States Intervention in Central America. New York: Harper & Row.

RAMADA CURTO, Diogo. (2017). «Há um Estado Cultural que quer pôr o MNAA a render no circuito turístico». Expresso Online. 22 February 2017. Accessed: 30 March 2017. http://expresso.sapo.pt/cultura/2017-02-22-Ramada-Curto-Ha-um-Estado-Cultural-que-quer-por-o-MNAA-a-render-no-circuito-turistico

MIGNOLO, Walter. (2012). Local Histories/Global Designs: Coloniality, Subaltern Knowledges, and Border Thinking. Princeton, N.J.; Woodstock: Princeton University Press.

KILOMBA, Grada. (2013). Plantation Memories: Episodes of Everyday Racism. Munster: Unrast-Verlag.

KUSTER, Brigitta. (2007). «Sous les yeux vigilants / Under the Watchful Eyes On the international colonial exhibition in Paris 1931». EIPCP online. May 2007. Accessed: 30 March 2017. http://eipcp.net/transversal/1007/kuster/en

Footnotes