r

e

v

e

s

The 25th November 1975 corresponds to the end of the Ongoing Revolutionary Process. After the New State having been overthrown, as planned by the Movement of the Armed Forces, the Socialist-oriented provisional governments led by Vasco Gonçalves up till 19th September 1975 aimed at implementing a socialist revolution in Portugal. In his speeches to Portuguese workers, Vasco Gonçalves sought to engage men and women in the revolutionary process, in which education was a major tool to endow them with the necessary skills to implement economic, social and cultural change and, thus, build the Portuguese nation.[1] This is particularly shown in the programme of the V Provisional Government, in which the word «revolution» is written 30 times.[2]

In 2014, forty years had passed since the Carnation Revolution. The public policies of memory led by right- and left-wing governments showed that 25th April, known as the Day of Freedom, was more than a historical landmark of democracy. It was an instrument of political manipulation after 1975, conveying tension between two different discursive approaches to collective memory: a dominant approach, historically framed within Neo-liberalist ideology that expanded in the West after the end of the 1980s – and Portugal was not an exception, particularly after Cavaco Silva took office as Prime Minister of the 11th and 12th Constitutional Governments between 1985 and 1995 – and another approach, the memory of the resistance, relatively stifled up till 1994, grounded on authentic experience (Erfahrung), bound by the duty of, as a community, not forgetting the oppression and suffering inflicted during the New State.[3] Fernando Rosas argued that 25th November started the counter-revolutionary process, just like the military movement had set off the Revolution (Rosas, 2015: 202); As a generator of the process of democratic normalization, 25th November influenced the political, economic and social conditions that ultimately enabled Neo-Liberalism to flourish in Portugal. The prevalence of this ideological framework determined the development of the memory of the Portuguese Revolution during the last decades of the 20th century.

From 1985 and on, the years of the Revolution and of the Ongoing Revolutionary Period (PREC) were frequently referred to as years of distress and unrest and, simultaneously, the political elites avoided debating the long period of the dictatorship.[4] The access to the New State police files was denied to the public and public speeches were oriented towards the need to reconcile the past with the present to appease the Portuguese conscience, and let the course of memory move on. Up till 1992, the memory of resistance to the dictatorship was undervalued, particularly because of the economic and social crisis that followed the PREC. Governmental and economic elites put the blame on the revolutionary years as the causes of the crisis that followed the PREC and up till 1985. The memory of the New State oppression was publicly softened by the economic crisis, the late years of political confrontation, involving the decolonization and the revolutionary process (Loff, 2014: 63-64). The communist and far-left wing projects that had driven the Revolution at first were remembered after the 1970s as defeated and isolated missions. It was less the New State regime than the Revolution the centre of discussion, whilst a counter-revolutionary, conservative and nostalgic memory gradually blocked the memory of resistance; In addition, it enhanced the public perception of the Carnation Revolution as a negative landmark (Loff, 2014: 64).

Enzo Traverso argued that after the 1980s, movements towards the preservation of memory invaded the public space in Europe. The past was constantly reminded of in the present, in a media-amplified collective imaginary and associated to public commemorations (Traverso, 2005: 10-11). It was changed and reinterpreted according to the cultural and political needs of the countries. Traverso referred to the establishment of memory industries and tourism that became imperatives during this period. In Portugal, the restoration of historical centres, such as Loulé, Nisa, Tomar and Vila Real and inaugurations of museums, libraries and cultural centres between the end of the 1980s and up till 1994, illustrate ways through which the past was reified for mass consumption (Traverso, 2005: 11). These attempts, however, did not include the preservation of the memory of the suffering of the victims of the New State, such as prison facilities and the PIDE headquarters in Lisbon.[5] Instead of being preserved and cherished, the memory of the past was reconstructed and, thus, politically more overtly controlled. Sites of memory, an expression coined from Pierre Nora’s lieux de memoire (Nora, 1989), were used to buttress the Portuguese national identity upon them.

The Revolution was reinterpreted as part of a modernized and functional nation and the official speeches delivered on every 25th April argued that freedom had been the major political achievement of 1974, and that much work was to be done: this meant strengthening the country’s economic resources. In 2004, the slogan for the 30th anniversary of the Revolution was Abril é Evolução. The commission of the official commemorations was mainly composed of political historians and political scientists; commemorations were oriented towards the analysis of the first three decades of Portuguese democracy because the first generation born after the Revolution had been raised in democracy.[6]

On 25th April, at Parliament ceremonies, right-wingers did not use lapel carnations as worn by left-wingers until the early 2000s. They did not conceal the burden the memory of the Revolution constituted for them. In fact, only after 2002, did a few right-wing members of Parliament (MPs) wear carnations for the first time. On the one hand, most of these MPs were born in the 1950s and 1960s. This might suggest the extent to which carnations had become depoliticized props for them. Many right-wing MPs wore them at the 40th anniversary, when Portugal was enduring the effects of a third bail-out. This fact alone, Manuel Loff contended, showed the extent to which the right-wing party was wary of debating the memory of the Revolution which loomed over the government when the economic recession worsened standards of living (Loff, 2014: 138). These were times when the protests were back on the streets and Grândola Vila Morena was again sung as a symbol of resistance to the government’s austerity measures.

The emergence of obsessive individualism was a characteristic of modernity. Walter Benjamin had argued that the end of the I World War had been responsible for the decline of authentic experience, having replaced it by lived experience (Erlebnis). Traverso emphasized that during the second half of 20th century the figure of the witness was of key importance in the representations of memory (Traverso, 2005:16). In Portugal, during the mid-1990s, the reconstruction of the memory of the Revolution gave voice to the PIDE torturers and to the military who had participated in the massacres in Africa.[7] The memory of the dictatorship and of the Colonial War invaded media space and perpetrators were given the opportunity to show their humanity, their suffering at times when circumstances and the regime had made them do as they had done (Loff, 2014: 99-103).

After the 20th anniversary, and in view of historical revisionism, the memory of resistance emerged and conquered visibility. Documentaries on political arrests, with testimonies of former political prisoners were produced; the decision to set up the Museum of Resistance in Peniche fortress was taken in 2007 and the association Não apaguem a Memória (Do not erase Memory) was set up following the municipal decision to convert the former headquarters of the State police into a luxury complex in 2005.[8]

Manuel Loff contended that the documented memory of 1974 and that of the resistance to the New State lack balance and accuracy because there is not enough material documentation of the resistance led by the Portuguese peasantry and proletariat (Loff, 2014:129). The establishment of archives, such as 25th April Documentation Centre at Coimbra University (1984) and Mário Soares Foundation (1991) were based upon strategies of collecting testimonies and documents that little ensured social and regional representativeness of the movements of resistance. In fact, the educated opposition could afford more resources to resist the New State. Moreover, the provisional governments were led by the educated bourgeoisie whilst the working masses had the decisive role of supporting the revolutionary process. Hence, the political and social role of most memory narratives overrate the representativeness of the republican and socialist middle class and university student movements. In addition, this imbalance met the needs of the emerging narrative on Portuguese democracy that was grounded upon the bourgeoisie hegemony against the contributions of the proletariat and peasantry. An example was the exhibition Liberdade e Cidadania. 100 anos portugueses, inaugurated at 25th anniversary of the Revolution whose text, entitled «Um século republicano» and signed by President Sampaio, emphasized the relevance of the republican tradition throughout the history of Portugal.

Towards the end of the first decade of 2000s and after, when the government led by Passos Coelho imposed severe austerity measures and the Portuguese demonstrated on the streets, several symbols of the Carnation Revolution were used – Grândola Vila Morena interrupted official events; Acordai was sung in front of the President’s official residence; carnations and black flags symbolizing hunger were used to convey the anger and frustration of the population on the streets. Besides popular demonstrations, protest murals documented the spirit and the iconography of the social protest.[9] During the late years of the New State, graffiti had been used to protest the Colonial War and, after 1974, murals conveyed the atmosphere of hope and enthusiasm during the revolutionary years. This art, fundamentally used by political parties, such as the PCP (Portuguese Communist Party) and the PCTP/MRPP (Portuguese Workers’ Communist Party/ Reorganization Movement for the Party of the Proletariat), was ephemeral and by the late 1990s, most of those murals had been washed off the walls on the streets. Nonetheless, their memory was preserved by the 25th April Documentation Centre at Coimbra University. The persistence of the historical memory of 1974 was important for the younger generation of street artists who started their artistic activity in the early 2000s to understand the heritage left by their predecessors, who had worked in a different political and social context, because it opened pathways of understand the legacy of this art as political intervention in Portugal (Câmara, 2015: 219). Not only was this dialogue important for the work of street artists but it was also equally relevant to the work of the second generations of writers, musicians and artists in general about the Carnation Revolution.

This article examines a short film, A Caça-Revoluções (The Revolution Hunter), directed by the young filmmaker and producer Margarida Rêgo, shown at Indie Lisbon cinema festival in 2014, and the murals painted by the collective initiative 25 de Abril 40 Anos 40 Murais in Greater Lisbon, also in that year.[10] In this film, a 25-year-old woman is determined to understand the full significance of 1974 and, aided by a 65-year-old man. Within the framework of the APAURB (Associação Portuguesa de Arte Urbana/ Portuguese Association of Urban Art), António Alves, former muralist of the PCTP/MRPP, decided to invite muralists to paint forty murals in Lisbon and in other cities (Loures, Aveiro, Ovar, etc.) to celebrate the 40th anniversary of the Revolution. 25 de Abril 40 Anos/40 Murais was open to individual and team applications. The purpose was to bring different generations of Portuguese muralists together to express the significance of the 1974 Revolution in 2014.[11]

This article argues that, despite the hegemonic Neo-Liberalist influence, in the 21st century and, particularly at a time of economic and social crisis, the activation of the memory of the Revolution is a fertile act of resistance because it combines resistance, utopian pursuit and historicity. The economic crisis and the lack of alternative successful ideological projects enhance the relevance of this memory in 2014; the upsurge of interest in utopianism at the end of the 20th century has made the emergence of the Carnation Revolution as the Portuguese social utopia for the following century.

The Portuguese Revolution has been publicly perceived as an exemplary case in view of the action of the military forces and the support of the people. The action of the New State police to repress the military people on 25th April, resulting into four dead and the forty-five-injured people was not counted in. The killers were supporters of the overthrown regime. Nonetheless, in the late 1970s, Eduardo Lourenço had argued that this perception was unrealistic because the Portuguese nourished their collective imaginary with idealism to minimize the effect of economic ills on national pride (Lourenço, 2000: 51). More recently, Onésimo Teotónio Almeida has pointed out that 25th April 1974 emerged as a utopian construct stemming from Marxism on the establishment of a new world and the rebirth of a new man (Almeida 2017: 295). The Revolution, as a catalyst for Portuguese democracy, was a utopianically-based, socialist-oriented project. Vasco Gonçalves, the Prime Minister of the II-V Provisional Governments (1974-1975), was the major advocator of the utopian potential of the Revolution, and continued to be so even after the PREC collapsed in 1975.[12] Vasco Gonçalves’s speeches drew inspiration from his reading of Mariatégui and Che Guevara’s socialist utopias to regenerate the Portuguese society based on equal opportunities, justice, solidarity and collectivism and through educating the people in these values.

Therefore, the Carnation Revolution is the Portuguese militant utopia that emerges as the offensive to the prevailing culturally conservative and revisionist Neo-Liberalist rhetoric. This is clear in the artists, filmmakers and writers, among other cultural producers, born after the Revolution, who discuss the democratic regime they inherited.[13] The concept of militant utopia was drawn from Paul Singer’s and António Teixeira Fernandes’s studies. Singer argued that the social revolution of Socialism is the utopian mode of production that can compete against the Neo-Liberalist economic system and its capitalist mode of production; thus, it is a deterrent to the collapse of democracy (Singer, 1998:82). Teixeira Fernandes contended that militantism encourages the pursuit of utopia to overcome a crisis (Fernandes, 1996:14). Utopias emerge in any place where meaning is a pursuit. The regenerating and healing effect of the Carnation Revolution as the 21st century militant utopia shows that the Revolution is a praxis, thus, conveying the relevance of the phrase «Falta cumprir-se Abril» in 2014.

In A Caça-Revoluções (The Revolution Hunter), photographs taken in the streets of Lisbon in 1974 are shown one after the other, and the plot is based on their historicity. In this sense, they – and murals also do it - articulate history and memory. Filmmaker Agnès Varda considered cinema and photography two complementary arts because life instants, frozen bits of reality, captured by cinema technology could trigger off the process of memory. One cannot help remembering Varda’s work when watching A Caça-Revoluções (The Revolution Hunter). The association between these arts is a way to put the texture of documentary into fiction, intertwining past and present. The female voice-over warns us of that in the beginning: «There are stories that begin as if they had already existed. As if the present was only the past. And the past was the only thing that we had to explain the present.» Time is a construct and cinema montage enhances this particularity. Deleuze and Guattari developed the concepts of crystal-image and ritornello as coalescent forms of reminiscence and reality, capturing moments, places and sounds that enable new time and place configurations to discuss the present with a view to the future. In A Caça-Revoluções (The Revolution Hunter), the images of the people on the streets of Lisbon represent the crowds celebrating the Revolution in 1974 and the street demonstrators against the bail-out programme in 2014. Étienne Balibar claimed that the past becomes a representation of the future through revolutions because new possibilities or frames of expectations are opened in a renewed manner (Balibar, 2017). These possibilities are configured as militant utopias that stimulate imagination. This is what Balibar calls the revolutionary praxis, and in Rêgo’s film, its significance is enhanced with the trope of the hunter. This is also an implicit trope in Sérgio Tréfaut’s Outro País (Another Country/ 2015), another film about the Carnation Revolution, in which the interviewed foreign photographers and filmmakers stated that they had dashed to Portugal to capture the collective enthusiasm in what they believed to be a one-off moment because accounts abroad could not get it right. In A Caça-Revoluções, (The Revolution Hunter) hunter and prey do not coincide in time: «She stared at him as he was starting, and she hunted. She stared at him fighting and she hunted. She stared at him in the middle of the rallies and she hunted. She stared at him reading those books of ideas and ideologies and she hunted. She stared at him singing those songs and she hunted. She stared at him writing those verses and she hunted». The enthusiasm felt by the Portuguese and hunted by photographers and filmmakers in 1974 expresses the millenarianist belief in the Revolution as the expression of a better future as the end of injustice and oppression culminated by the overthrow of the New State. However, it is closer to Eduardo Galeano’s O Caçador de Histórias (Hunter of Stories), in which storytellers are hunters in the pursuit of the past memory to understand the present with a view to the future.[14]

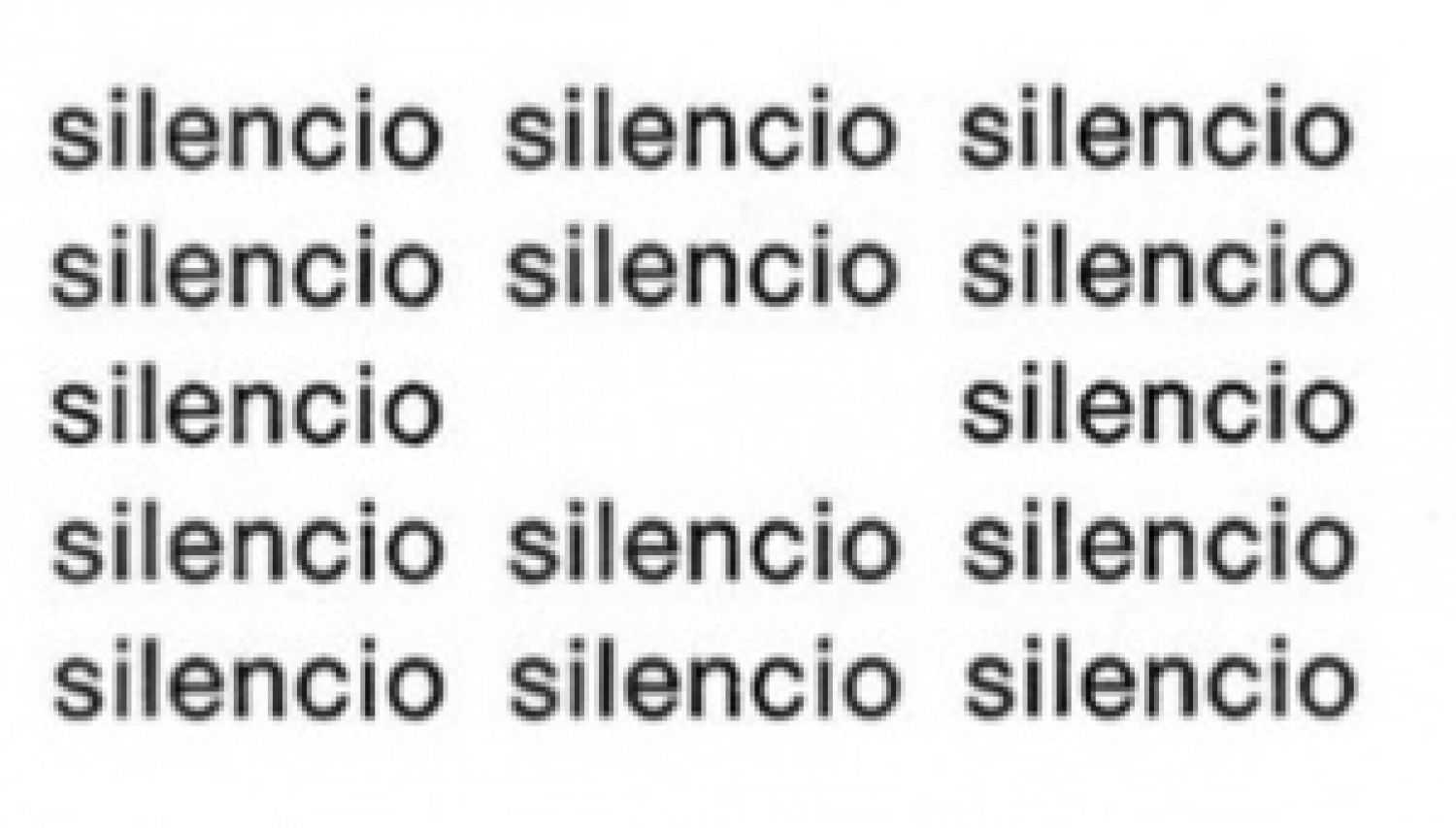

In 2014, democracy is the regime no one intends to overthrow. The Carnation Revolution emerges as a possibility to overcome social disquietude and frustration. This revolutionary praxis is also conveyed through ritornelos: Carlos Paredes’s guitar in his A Noite; Adelino Gomes’s voice on a live recorded radio footage on 25th April 1974; and the sound of the steps preceding the cante «Grândola Vila Morena» evolving into that of the steps of the Portuguese demonstrating on the streets. Teixeira Fernandes contended that imagination seeks solutions in desiderative constructed alternatives, these have the potential of transforming society (Fernandes, 1996: 13). As a historical reference in 2014, the Carnation Revolution offers the Portuguese the possibility of becoming a symbolic refuge from economic and social injustice (Fernandes, 1996:13). In Outro País (Another Country), Sebastião Salgado, who had been in Portugal in 1974 and visited the country again some years later, pinpointed the decline in popular enthusiasm after the revolutionary process had ceased. The voice-over in A Caça-Revoluções, (The Revolution Hunter) concluded that time was the key to understand the Revolution in 2014: «what she was looking for was in the space between them». The future is prepared when the past is discussed in the present; a mythification of the past is meaningless because, as the voice-over concludes, «that beast was never made to be hunted». Teixeira Fernandes contended that militant utopias result from a constant millenarianist pursuit and the utopian quest against social imbalance (Fernandes, 1996:14). As Balibar contended, «this can be another way of thinking, imagining, doing the revolution, infusing the same name with a different meaning linked to different experiences» (Balibar, 2017). In the murals sponsored by the APAURB, the messages «Contra a Precariedade/Estivadores em Luta/Pelo Direito ao Trabalho» (Against Precarity/Dock Labourers struggle/ for their right to Work); «Em frente na Luta pelo Pão» (Fighting for the breadwinning right); «Abril/Força/Revolução» (April/Strength/Revolution) and «Eles comem tudo» (They eat everything) convey less the historical memory of the Portuguese proletariat’s struggle for labour rights and against exploitation than their adequacy as the expression of the social frustration felt in 2014.

Heroes start revolutions. A comparative reading of the Portuguese street art on the Carnation Revolution produced in the 1970s and in 2014 shows that murals relied on the representation of heroes, but their political relevance declined between the 1970s and the 2000s as the process of memory of the Revolution became less politicized. Street art constitutes conversation, interpretation and participation in tradition (Irvine, 2012: 263). In Portugal, the present-day tradition of street art is closer to the North-American practice, in which mass consumption, pop iconography and figurative imagery are its correlates. The European tradition is engaged in combining practice with poetic, political and philosophical thoughts (Campos, 2014). The murals on the Carnation Revolution combine political message with figurative emphasis. Lenin, Stalin, Marx and Che Guevara were the few political figures represented as heroes or inspiring figures for the Portuguese Marxist socialism-oriented project during the PREC. They were the political symbols of the Portuguese millenarianism in the 1970s. Murals also used figurative motives: they were mostly representations of families, the peasantry and the proletariat.

In 2014, the memory of the Portuguese Revolution relied on the centrality of the Portuguese people as the hero collective. The Revolution was possible because of the massive support of the Portuguese people who occupied factories, large estates, and precarious houses; learned self-management and collective forms of management; and held the control of the major business sectors. The concept of heroship is rooted in the action of transforming a new society; the political programme of the V Provisional Government stipulated that the collective involvement of the Portuguese society was the only way to stimulate progress. This was the first time that a political programme stipulated this, but the published history of Portugal shows us that the Portuguese people, that is the working class, have been depicted as the wisest and most sensible decision-makers. In addition, this pattern has contributed to construct the Portuguese exemplariness which has been the core of the «Portugalidade» to ignite national pride. For example, in Fernão Lopes’s chronicles, the Portuguese people show the characteristics of heroes, such as courage, sensibility and wisdom. Had the Master of Avis not received the support of the Portuguese people, the plots of Spanish monarchy and the Portuguese nobility would have been successful; similarly, had the Portuguese people not supported the Movement of the Armed Forces, the coup d’état would have failed completely. In A Caça-Revoluções, (The Revolution Hunter), personal names are replaced by a «she» and a «he». Without names and without bodies – the voice-over tells the story, but characters are never visible: the woman and the man stand for two Portuguese generations only.

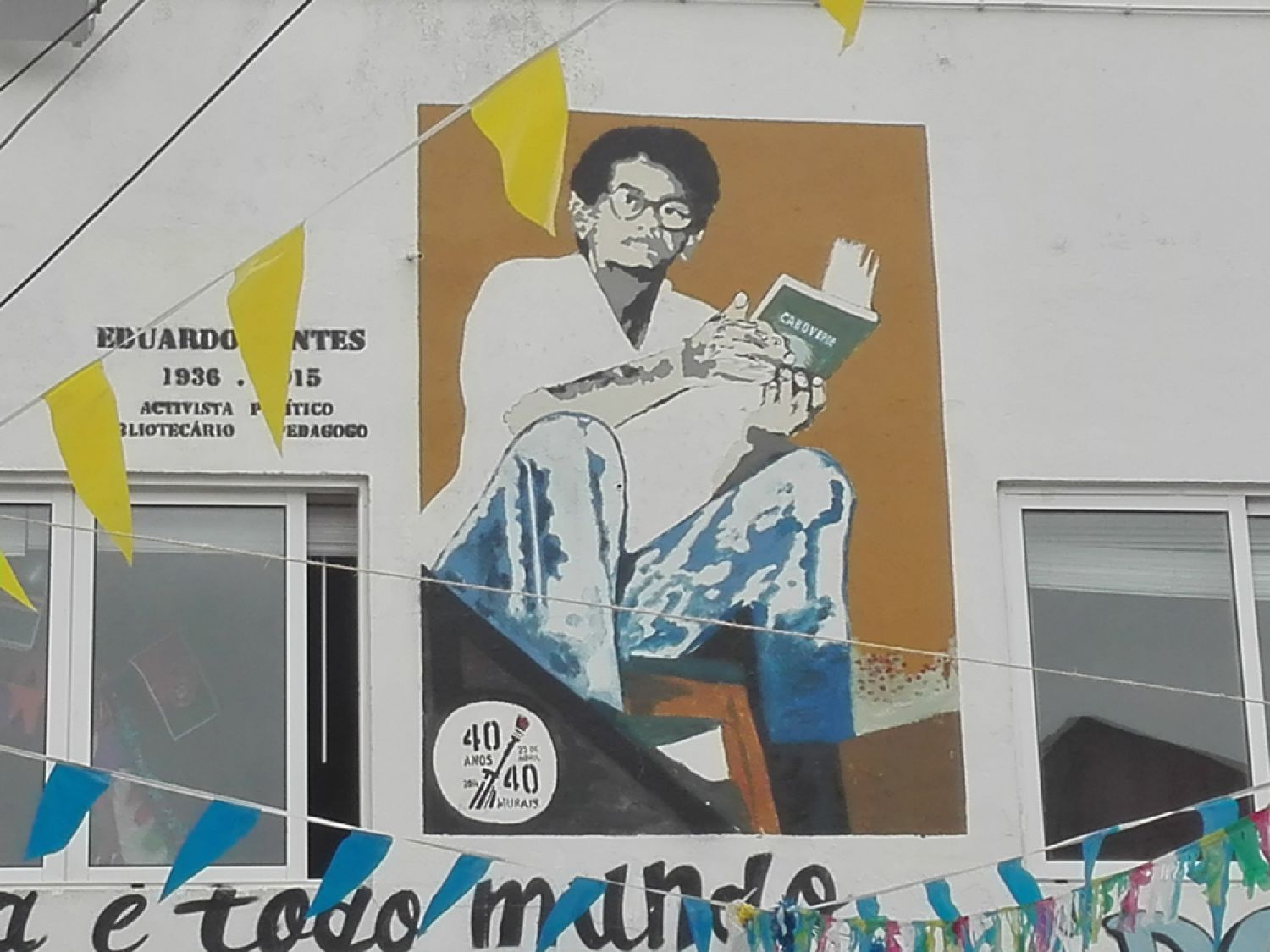

The few identifiable Portuguese figures represented in the APAURB-sponsored murals are, as follows: Zeca Afonso, Maria de Lourdes and Father Max, Ribeiro dos Santos, Amilcar Cabral and Eduardo Pontes.[15] Zeca Afonso is the singer-songwriter of Grândola Vila Morena, which was the second signal to start the coup on 25th April 1974. The song was broadcast on Radio Renascença because one month earlier, Zeca Afonso had played it at a concert in Lisbon and the audience had joined in enthusiastically. Moreover, he participated actively in the PREC through his songs, politically engaged, and through his support to the Marxist socialism-oriented project.

Maria de Lurdes and Father Marx, allegedly murdered by the counter-revolutionary movement MDLP in 1976, although the circumstances of their assassination have not been totally explained and their perpetrators have never been condemned in court. Maria de Lurdes and Father Max taught adult workers in Trás-os-Montes. The phrase «Não vos mataram. Semearam-vos» conveys the key importance of their mission.

Hannah Arendt contended that totalitarianism annihilated the contemporary condition of martyrdom because it had stripped martyrs off their personal identity and social existence (Arendt, 1998, p. 496). The mural of Maria de Lurdes and Father Max in 2014 depicts the individual suffering who died at the hands of the counter-revolution. Ribeiro dos Santos was a student of Law murdered by a PIDE policeman in 1972. Together with Maria de Lurdes and Father Max, his death is elevated to martyrdom, to enhance the cruelty of the New State and the counter-revolutionary movement. Thus, and despite the long-standing hegemonic depoliticized memory, the memory of 1974 in 2014 is centred less on the victorious establishment of the political mission in 1974 than on the disastrous social consequences of the revolutionary process having been crushed in 1975. Teresa Caldeira contended that street art introduces order in sensitive issues («certa ordenação do sensível») (Caldeira, 2012). The murals of 25 de Abril 40 Anos 40 Murais expose the tension emerging from the memory of a coup d’état that did not evolve into a complete revolution.

The Colonial War was a major factor to the outbreak of the Carnation Revolution. In fact, the first sentence of the programme of the Movement of the Armed Forces reads that the decision to overthrow the Government was due to the inability of the New State to define a solution for the war.[16] Nonetheless, this fact is almost secondary in the representation of the Revolution in 2014. It is worth mentioning that the memory of the experience of the war exists, but it is dissociated from that of the Revolution. The link between both implies associating the memory of colonialism and decolonization and the sympathy of many Portuguese soldiers with the movements of African liberation. As mentioned above, this was the debate that the right-wing avoided engaging, and opted to discuss the memory of the Revolution in social terms, a decision that depoliticizes the figure of the soldier. It is a «whitewashed psychic» Revolution (Gil, 2004: 16). Thus, the figure of a depoliticized – and thus, demilitarized - soldier is a visual representation of a revolutionary, one of the people, in the pursuit of social changing. The persistence of this visual memory exposes the tension that this association introduces into the collective memory.

In A Caça-Revoluções, (The Revolution Hunter), the conversation between him and her begins with the affirmation of his preference for Picasso’s mural Guernica, a tribute to the memory of the Spanish civil war and to the devastation caused by the Condor Legion, ally of Franco during the civil war. The bull is the epitome of brutality and war devastation; and it is also the artist as an «embodied warrior, the wild animal that doesn’t subject to human rules» and later it is also the Revolution, «that beast was never made to be hunted» and needs a man to grab it «by the antlers like a sturdy hunter». This is explained with a sequence of photos of a Portuguese bullfight. As crystal-images, in 2014, these pictures conjure the memory of the colonial war – the latest war in the History of Portugal – and the need to decolonize the Portuguese collective imaginary; this is part of the revolutionary praxis that cannot be stopped because «she was the one that had to go and fight in the arena with the bull».

As far as murals are concerned, the tension generated by the association of decolonization with 1974 is shown in the decision of representing Amílcar Cabral and Eduardo Pontes in the 40 Anos/40 Murais initiative. They are the only political individualities represented in these murals: Amílcar Cabral, the PAIGC leader murdered by PAIGC dissidents plotted with the DGS in 1973; and Eduardo Pontes, former activist, political prisoner during the New State, and one of the founders of the communitarian project Moinho da Juventude, Cultural Association in the peripherical neighbourhood of Alto da Cova da Moura, in Amadora, mostly dwelt by Cape Verdeans who came to Portugal in 1977. Amílcar Cabral was represented twice: in a small mural in Alcântara, in the centre of Lisbon, and in a large mural on the façade of a building in Amílcar Cabral Avenue, in Quinta do Mocho, another neighbourhood mostly dwelt by Cape Verdeans and Guineans in greater Lisbon.

The large mural of Eduardo Pontes is on the façade of Moinho da Juventude. The larger murals were painted by António Alves and are located in the periphery of Lisbon.

Urban planning establishes an intramuros/extramuros symbolic logic to define inclusion and exclusion (Irvine, 2012: 246). The relevance of political activism in street art is determined by its public visibility (Campos, 2016). Where the mural is painted is not less important than what the mural is about. Whereas the mural of Amílcar Cabral in Alcântara, next to another with the flags of the Portuguese-speaking African countries, is smaller and integrated into a sequence of other murals about the Revolution, António Alves’s murals of Amílcar Cabral and Eduardo Pontes cover the façades of the buildings. Moreover, the mural in Quinta do Mocho is in the avenue that delimitates this neighbourhood from the direct road access to Lisbon and separates the underprivileged from upper-class families.[17] This exposure makes this avenue a space of transition, the heterotopia that confronts the visitor with the reality of exclusion. The mural signals the memory of the anticolonial resistance and the Guinean and Cape Verdean dwellers reactivate this memory by preserving this mural. The words Unidade e Luta (Unity and Fight), the PAIGC motto, - non-existent in Alcântara - underpin the right to resist social exclusion. In Alto da Cova da Moura, the mural of Eduardo Pontes activates the memory of resistance to social and cultural marginalization.

The visibility of these murals in the urban texture illustrate the effect that the Neo-Liberalist ideology had on the process of memory of the Revolution; the tension from confronting the 1974-1976 political memories – particularly those associating the liberation of the Portuguese-speaking African countries with the Carnation Revolution – is not visible in the city centre. Nonetheless, being out of sight does not mean that it is non-existent. On the contrary, the discursiveness of this memory persists and the fact that it is visible in the periphery conveys that there are wounds to heal. It is not a coincidence that the author of both murals was António Alves, the activist who started graffitiing in the late years of the New State. His intervention is the most political because it stems from the memory of resistance. It exposes the social imbalance that 1974 did not sort out and, thus, the extent to which the programme of the V Provisional Government constitutes a valid militant utopia in the 21st century.

In conclusion, the need to reconfigure production and social structures to overcome recession and social problems exacerbated the millenarianist impulse. The historical anniversary of the revolution was the moment to show that the collective memory configures it as the socialism-oriented utopia to overcome the failure in 1975. When the film A Caça-Revoluções (The Revolution Hunter) indicates that the full perception of the significance of the Carnation Revolution in 2014 is reached when the continuous individual praxis reconstructs meaning of the past; and when the murals on the Carnation Revolution convey that particular figures and values of the past make meaning in 2014, they stand as recipients of the legacy of a historically and politically defined project – the Carnation Revolution which took place in 1974 and as a socialist project collapsed in 1975 – and acknowledge that the political memory associated to this project resonates with the resistance urged at times of economic recession and social unrest, projecting it as a legitimate militant utopia. That is, perhaps, the reason why the murals in the periphery of Lisbon and whose connotation is most overtly political are the only ones preserved in 2017.

Acknowledgements: I am grateful to Margarida Rêgo for giving me permission to watch her A Caça Revoluções/ The Revolution Hunter, without which it would have been impossible to discuss it in this article.

Bibliography

ARENDT, Hannah. (1998). As Origens do Totalitarismo. Trans. Roberto Raposo. 3rd ed. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras.

25 de Abril, 40 Anos 40 Murais. Disponível em http://40anos40murais.weebly.com/murais.html

ALMEIDA, Onésimo Teotónio de. (2017). A Obsessão da Portugalidade. Lisbon: Quetzal.

BALIBAR, Étienne. (2017). «The idea of Revolution: Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow». Prepared for the Keynote Lecture, International Society for Intellectual History Conference: «Rethinking Europe in Intellectual History», University of Crete, Rethymon, 3 May 2016; revised with some changes and a new conclusion on May 6 at the Megaron Lecture Hall in Athens, as part of the «Birkbeck in Athens Lectures in Critical and Cultural Theory». Available on http://blogs.law.columbia.edu/uprising1313/etienne-balibar-the-idea-of-revolution-yesterday-today-and-tomorrow/.

CALDEIRA, Teresa Pires do Rio. (2012). «Inscrição e circulação: novas visibilidades e configurações do espaço público em São Paulo». Public Culture. vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 385-419; republished in Novos estudos – CEBRAP, no. 94. Available on http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0101-33002012000300002.

CÂMARA, Sílvia. (2015). «Alguns Factores Determinantes para o Impacto da Arte Urbana em Lisboa». Convocarte: Revista de Ciências da Arte., no.1, pp.215-229.

CAMPOS, Ricardo. (2014). «Ensaio Visual: A luta voltou ao muro». Análise Social, 212, XLIX.

CAMPOS, Ricardo. (2016). «Visibilidades e invisibilidades urbanas», Revista de Ciências Sociais. vol. 47, no.1, pp. 49-76.

Carta do Movimento Cívico Não Apaguem a Memória. Available on http://maismemoria.org/mm/carta-do-movimento/.

CASTILHO, Clara. «40 anos depois – Abril de novo nas Paredes das Cidades». Available on https://aviagemdosargonautas.net/2014/04/19/40-anos-depois-abril-de-novo-nas-paredes-das-cidades-por-clara-castilho/.

FERNANDES, António Teixeira. (1996). «As utopias militantes como lugares de constituição de sentido». Paper delivered at XV Congrès International de TAISLF on L’Invention de La Société. De TÉlucidation à Paction, Évora, 8-12 July 1996. Available on http://ler.letras.up.pt/uploads/ficheiros/1390.pdf.

GONÇALVES, Vasco. Discursos, Conferências de Imprensa, Entrevistas. Intr. J.J. Teixeira Ribeiro. Porto: Augusto Paulo da Gama, 1976. Available at https://www.marxists.org/portugues/goncalves-vasco/1975/05/17.htm

GALEANO, Eduardo (2016). O Caçador de Histórias. Lisbon: Antígona.

GIL, José. (2004). Portugal, Hoje: O medo de existir. Lisbon: Relógio d’Água.

IRVINE, Martin. (2012). «The Work on the Street: Street Art and Visual Culture». Sandwell, Barry & Heywood, Ian (eds). The Handbook of Visual Culture. Berg, pp. 235-278.

LEVITAS, Ruth (2001). «For Utopia: The (Limits of) Utopian Function in Late Capitalist Society». Goodwin, B. (ed.), The Philosophy of Utopia. Ilford: Frank Cass Publications, 25-43.

LOFF, Manuel (2014). «Estado, democracia e memória: políticas públicas e batalhas pela memória da ditadura portuguesa (1974-2014)». In Loff, Manuel, Piedade, Filipe, Soutelo, Luciana Castro. (2014). Ditaduras e Revolução: democracia e políticas de memória. Lisbon: Almedina, pp.23-143.

LÖWY, Michael (2016). Utopias. Lisbon: Ler devagar.

LOURENÇO, Eduardo (2000). O Labirinto da Saudade: Psicanálise mítica do destino português. Lisbon: Gradiva.

NORA, Pierre. (1989), «Between Memory and History: Les Lieux De Mémoire.». Representations, 26, pp. 7–24.

PINTO, António da Costa. (Ed.) (2004). 25 de Abril: os desafios para Portugal nos próximos 30 anos. Lisbon: Presidência do Conselho de Ministros/Comissão das Comemorações dos 30 anos do 25 de Abril.

Programa do Movimento das Forças Armadas. Centro de Documentação 25 de Abril, Universidade de Coimbra. Available on http://www1.ci.uc.pt/cd25a/wikka.php?wakka=estrut07.

Programa do V Governo Provisório. Available on https://www.historico.portugal.gov.pt/pt/o-governo/arquivo-historico.aspx

ROSAS, Fernando. (2014). «Ser e não ser: A Revolução portuguesa de 74/75 no seu 40º aniversário». In Loff, Manuel, Piedade, Filipe, Soutelo, Luciana Castro. (2014). Ditaduras e Revolução: democracia e políticas de memória. Lisbon: Almedina, pp.195-205.

SINGER, Paul (1998). Uma Utopia militante: repensando o socialismo. Petrópolis: Vozes.

25 de Abril, 40 Anos 40 Murais. Available on http://40anos40murais.weebly.com/murais.html.

A Caça-Revoluções. Director and Producer Margarida Rêgo. Portugal, UK, 2014.

Outro País. Director and Producer Sérgio Tréfaut. Portugal, 2015.

Footnotes