r

e

v

e

s

To explain my point I want to start setting out a very general premise about the role of the image in the thought-making process: images are produced by the memory, unconsciously, and projected into our conscience. Then, when we become aware of these images, we begin to think, to have ideas, to verbalize. This is a process related to the subconscious, to the senses, to the fears and desires. It is not necessary to explain that visual art has something to do with images, although after Duchamp it seems to be a function of language and not of revelation (Solomon-Godeau, 1984, p. 76). But as we all know, we specialists in museum theory, curating, and similar disciplines, art is also, and above all, an institution. And institutions have less to do with images and much more with power relations.

This agonistic ethos hides inside modern art from its very beginning. Since the organization of the first exhibition in 1665, and of course since the founding of the first public art museum, the Louvre, in 1793. Modern Art has tried to straddle sets of impossible dualities in bourgeois culture: public/private, historical/timeless; handcrafted/industrial; individual/collective, universal/discriminatory, and so on. And the task of the Art Institution is not only to create an autonomous sphere where these contradictions seem to evaporate, but to find a balance between the irrationality of artistic practice and the scientific display of the exhibition. Bennet describes the museum as a rational and scientific space of representation (Bennet, 1995, p. 1), and the exhibition itself came to reinforce a new epistemology.

I like to distinguish the Art Institution from the Art Institutionality. The first is an abstract idea that includes not only bureaucratic and market structures, but ideologies, its own history, the exhibition as main technology for art socialization…, and a dense network of interconnections with other institutions, like the bourgeois subject, an elusive idea of public, the rational-scientific knowledge, etc. With the term «Art Institutionality» I refer only to the bureaucratic and market structures, including the academic ones, like this conference. A huge apparatus that makes art possible, canceling at the same time the possibility of new art.

As art institutionality grows, a special sphere of experience crystallizes, (I’m quoting Peter Bürger), until a time comes, with the historical avant-garde movements, when the social subsystem that is art enters the stage of self-criticism (Bürguer, 1984, pp. 22-25). This is very interesting, because for a century we all know that art is a social system, and our focus should be on the social processes that produce meaning, not more on artworks. Or not only, because artworks are still alive. However art criticism, curating, museology and all kind of art theory are still speaking about artworks. And usually pointing out the permanent failure of art as a revolutionary force. Why? This is a good question.

Art history is based on individual subjects, the artists, and particular objects, the artworks. As much, we speak about «art movements», which is a simplification. Maybe useful, but hard to take seriously in the present. And while museums were dealing with Institutional Critique as the last «modernist impulse in an era when that impulse was no longer believed or understood» (Blake Stimson, 2009, p. 31), many artists had already understood that what matters is no longer what you do, but how, where, when and with whom you do it. The question is not to put another critical work within the institution — whether museum or the market — because this artwork is predetermined by it.

Around 1970 there began a paradigm shift in artistic creation, which until very recently has been ignored by the hegemonic Art Institutionality. I’m speaking about the alternative art scene, that blew up in two consecutive waves: the first one at the end of the ’60’s and early ’70’s, with spaces like 112 Greene Street, The Kitchen or Museo del Barrio in New York; Woman’s Building in LA, San Francisco Museum of Conceptual Art, NGbK in Berlin; Zone in Florence, Italy; Hallwachs in Buffalo; Space and ACME in London… And the second one in the ’90s, with spaces like Bank in London or Ojo Atómico in Madrid.

In this brave new art world artists have needed to organize themselves. They needed and still need to create autonomous spaces and to provide mutual support for a collective that had become subaltern after a new division of labour in this hiperinstitutionalized system. This is a generation that feels that it was no longer possible to do art under the institutionality that exploded at this time. We can find a lot of testimonies by artists in the sixties and seventies, expressing their concern with this question: the controversy between Daniel Buren and Harald Szeeman in 1969; Mel Ramsden saying in 1975: «Consider the following: that the administrators, dealers, pundits, etc., who once seemed the neutral servants of art, are now (especially in New York) becoming its masters.» Allan Kaprow proposing in 1967 that «the modern museums should be turned into swimming pools and night clubs.» Robert Smithson declaring that «Cultural confinement takes place when a curator imposes his own limits on an art exhibition, rather that ask the artist to set his limits. Artists are expected to fit into fraudulent categories. (…) Museums, like asylums and jails, have wards and cells — in other words, neutral rooms called galleries.» etc.

It was really a new situation, because in the 19th and early 20th centuries Salons had always been organized by artists, sometimes with the support of critics, like the Sociedad de Artistas Ibéricos in the ’20s in Madrid. Anyway, the role of other agents was secondary. But this changed. As Jan Verwoert explains:

«…the transformation of the role of the curator from that of care-taker of the museum to that of an author of exhibitions has to be understood as the outcome of a general change of the division of labour in the art field during the late 1960s (…) The emancipation of the curator as a cultural producer (…) turned curator and artist into competitors.» (Verwoert, 2006, 132).

Fifty years later curators face the same contradictions as post avant-garde artists. And a big one is the fiction of the invisibility of the museum, that we can see the art without seeing the museum. Museums are not invisible: they have huge buildings, armed police, rich patrons… Invisible is only the section where power lies. Museums work as disciplinary institutions: as public, you are always watched, observed. The exhibitionary complex is turned upside down. It is an actual panoptic, and not only for artworks safety, but to guarantee your behavior, a respectful conduct like in a church. The old opposites dualities of nineteenth century museums have never been solved. Maybe curators have thought that all these contradictions were only artists’ concerns, but the truth is that, unlike the artists, the new bureaucratic class cannot focus its work on the institution itself, and unlike the artists, it cannot create other kinds of spaces: autonomous, ephemeral, moving, non hierarchical spaces. Nobody will pay a salary for that.

From my point of view the wide range of experiences that we can comprise within the notion of New Institutionalism tried to push the institution to alternative arenas. They have taken the experiences of self-organized art projects to apply it to the art centers at a moment when their social function was questioned, the art market having become more important than museums, and the artists seem to be less and less interested in exhibitions. Jonas Ekeberg recognised in an interview that «The most important inspiration [for institution’s renovation] came from artists’ initiatives». Or «This construction of alternative and mini-institutions should rather be seen in continuity with alternative and grassroots methods.» (Lucie Kolb & Gabriel Flückiger, 2013, pp. 21-22)

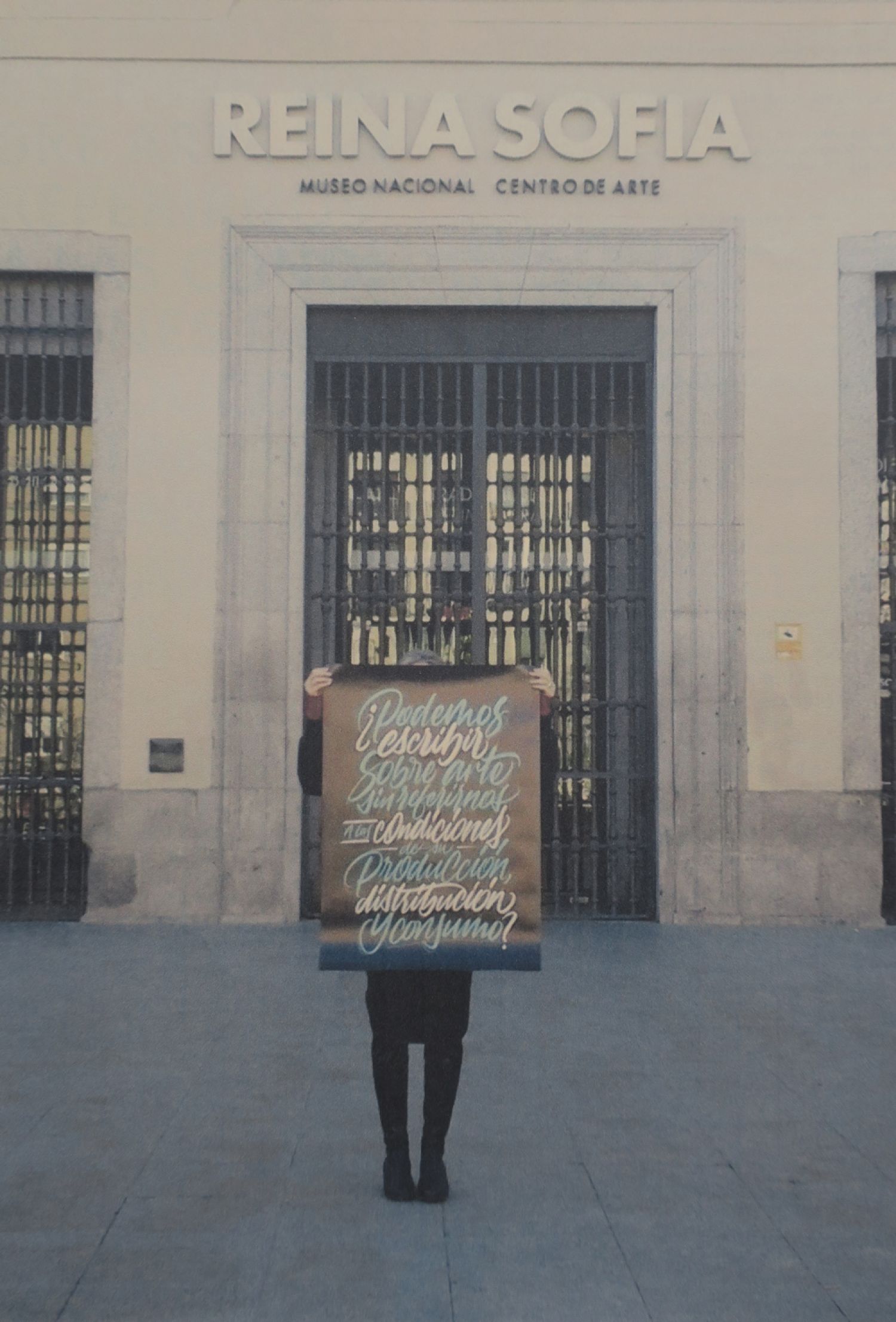

However, the consequence of this recognition has not been a far-reaching transformation of art institutions, but an institutionalization of this kind of innovative and critical practice. Some art centers disguise themselves as social centers, focusing on urban gardens, collective knitting, handcrafts, amateur theatre… Others try to legitimize themselves by transferring the lost transcendence of art into politics. In the first case, culture is understood as a leisure activity. Critical and actual political potentiality of art is gone. The latter simply move the question of autonomy from one place to another, leaving art as a servant of politics. It’s the case of Borja Villel first in Macba and then in Reina Sofía. And naturally his project has produced professional politicians, like Marcelo Expósito and other closer collaborators, instead of art or artists.

Today, New Institutionalism is called into question. We cannot speak about a collapse, but inconsistent results in the one hand, and the 2008 financial crisis, on the other, have caused the cancellation of paradigmatic centers like Rooseum in Malmo. There is a broad discussion about the effects of these experiences on institutional practices, as we can see, for example, in Oncurating magazine Issue 21: [New] Institution[alism] (2013). Or the present conference, that in its statement refers directly to New Institutionalism, radical museology and critical museology. But the discussion has always been between curators, between «institution people», who usually had never worked outside the institutional umbrella. And as Rachel Mader points out in her text for the aforementioned Oncurating 21:

«…the institution swiftly becomes representative of state-political power and superiority, in relation to which the subject must be submissive and obedient or else insist on a position of refusal and rejection. Critical agency within hegemonical structures is considered nearly impossible, since they are only interested in the extension of their own power.» (Mader, 2013, p. 37)

Arguments and counter-arguments are all centered around curatorial and managerial issues, but they cannot go out of the frame of art institutionality, because the players exist only based in institutions, in the real entity of a museum or art center. Something is lacking here, for there is a large universe beyond art centers, cultural policies and public budgets. We have to dig deeper to understand where the dysfunctions of renewed institutions lie.

Modernism understood politics as the destruction of an existing form of power with the goal of establishing a new one. The main way for politics, and for art, was revolution. Later art criticism maintained this position: art that cannot destroy the art system is failed art. Avant-garde has failed, and post-avant-garde seems unfeasible in these terms of radical change.

In fact, alternative art spaces are often criticized because they have not destroyed the art market or the whole art system. Art theoreticians and historians, and some artists linked to this scene, like Julie Ault, expected a revolutionary attitude from this movement of the last third of the 20th century. But most of the experiences were not inspired by the revolutionary-marxist tradition. We can identify them rather with an anarchist ethics. Or maybe with a feminist understanding of politics.

As Jacqueline Cooke explains:

«Avant-gardism has tended to be a theoretical discourse about strategy, whereas the alternative has tended to be defined (by practitioners) as an ethical discourse about practice.» (…) «the predominance of Marxian critique evident in existing literature and art practices is a problematic ‘plausible narrative’ which emphasizes an oppositional, dialectical stance.»

Plausible narrative is here used after Victor Burgin definition: «Real history therefore – mutable, heterogenous and undetermined – is kept prisoner in its own dungeons while a more coherent impostor (a more plausible narrative) takes public command and dispenses judgement.» (Burgin, 1986)

In her doctoral thesis Cooke analyses the alternative art scene in London during the 90s, and finds a contradiction between academic discourses about avant-garde art and actual art practices. Her conclusions are remarkable:

«The quality that I have called complex alternative space involves the use of available methods of critique, or the creation of new tactics to enable a restless movement or instability, to carry an argument, or to produce friction in circumstances that are not usually seen as changeable. Opportunistic rather than contingent, the aim is not to be a vanguard of opposition, not to change society, but to make space for individual voices, for contrary thoughts, sometimes called an ‘alternative consciousness’. What I have found in the research is productive disagreement, restlessness, an ‘alternative’ space for thought, a rejection or questioning of assumptions. It is not oppositional in the sense that it can defeat what it opposes, it accepts failure, or complicity. The mass of diverse and contradictory ideas and actions are themselves the complex ‘alternative’, this alternative is contentious.»

One of the goals of alternative projects was to create context for art, because meaning, value, is not an inherent quality of artwork. It’s not necessary to go back to Ferdinand de Saussure to explain that. As the Situationist artist Asger Jorn poetically expressed: «value does not emerge from the work of art, but is liberated from within the spectator…» (Jorn, 1998)

From this point of view, the institutional renovation is under the pressure of two opposing forces: The museum is an embodiment of the State, and as such, it works as an instrument of power. But contemporary art is understood as a critical practice, whose aim is to make visible and to deactivate the means at power’s disposal. The museum has to be hegemonic and antagonistic at the same time. Of course, this is impossible. And the museum does not have the ability to create different and simultaneous negotiating positions with the system or to produce the friction and the instability that Cooke pointed out.

The museum cannot create a context for art, because it is a context in itself. A context defined by the exercice of power. When the critical practices developed by the artists in their self organized experiences are co-opted by public institutions, the «complex alternative» disappears and the image-based practice is replaced by strategic discourse. Artists themselves are objects of research, management and curating, but no longer subjects with agency within the art space. Again, it’s about the old conflict between theory and practice, text and image. The agonistic ethos of modern art.

I think that only Rebecca Gordon Nesbitt, in her contribution to Ekeberg’s New Institutionalism, asked herself about the role of the artists in museums transformations:

«Following a gradual acceptance by artists and audiences of artists-led initiatives being absorbed into public institutions during the 1990s, organizations like Rooseum and Kunstverein München are attempting to reinvent themselves by adopting the methodologies of such initiatives, including a tendency to show process-based work, retaining the ability to react quickly to developments in the art world and consolidating artists’ networks with the institution at the center. (…) They take the existing institutional framework (…) as the starting point (…) One of the main pitfalls with this way of working is that artists and their activities are forced into a construct defined by the institutions that generally serves to flatter the institution and disempower the artists.» (Nesbitt, 2003, p. 84)

She ends by saying: «To close the gap that persists between artistic and institutional practice, maybe a new model needs to be born, from the ground up rather than the top down, which can respond more effectively to the needs of the artists.»

For me the question is not how to set up a new institutionalism, but how to de-institutionalize the public resources for art, in which museums are included. And I feel that artists are the unwanted guests at this dinner, although we provide and cook the meals.

Bibliography

AULT, Julie (ed.). (2002). Alternative Art, New York, 1965-1985. Minneapolis and Ney York: University of Minnesota Press and The Drawing Center.

BENNET, Tony. (1995). The Birth of the Museum: History, theory, politics. London and New York: Routledge.

BÜRGER, Peter. (1974). Theory of the Avant-Garde. Frankfurt: Suhrkamp Verlag. Minneapolis: Manchester University Press / University of Minnesota Press, 1984. Spanish edition: Ediciones Península, 1987.

BURGIN, Victor. (1986). «The End of Art Theory». The End of Art Theory. Basingstoke and London: Macmillan Education.

COOKE, Jacqueline. (2007). Ephemeral traces of ‘alternative space’: the documentation of art events in London 1995-2005, in a library. Unpublished Doctoral Thesis 2007, Goldsmiths University of London. Acessed: March 2017. http://research.gold.ac.uk/3475/

JORN, Asger. (1962/1998). Critique of economy policy Acessed: March 2017. http://scansitu.antipool.org/6005.html

KAPROW, Allan. (1967). «Where Art Thou, Sweet Muse? (I’m Hung Up at the Whitney)» in Alberro, Alexander and Stimson, Blake (eds.) (2009). Institutional Critique: An Anthology of Artists’ Writings. Cambridge MA and London: The MIT Press, pp. 52-55.

KOLB, Lucie & FLÜCKIGER, Gabriel. (2013). «The term was snapped out of the air» - An Interview with Jonas Ekeberg in Kolb, Lucie & Flückiger, Gabriel, «(New) Institution(alism)», On Curating, Issue 21, Zürich.

MADER, Rachel. (2003). «How to move in/an institution» in Kolb, Lucie & Flückiger, Gabriel, «(New) Institution(alism)», On Curating, Issue 21, Zürich.

NESBITT, Rebecca Gordon (2003). «Harnessing the means of production». Ekeberg, Jonas, New Institutionalism, Verksted 1. Norway: Office for Contemporary Art Norway.

RAMSDEN, Mel. (1975). «On Practice» in Alberro, Alexander and Stimson, Blake (eds.) (2009). Institutional Critique: An Anthology of Artists’ Writings. Cambridge MA and London: The MIT Press, pp. 52-55.

SMITHSON, Robert. (1972). «Cultural Confinement» in Flam, Jack (ed.). (1996) Robert Smithson: The collected writings. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London, University of California Press.

SOLOMON-GODEAU, Abigail. «Photography after art photography» in Wallis, Brian (ed.). (1984). Art After Modernism: Rethinking Representation. New York: New Museum of Contemporary Art. Spanish edition: Akal, Madrid, 2001.

STIMSON, Blake. «What was Institutional Critique» in Alberro, Alexander and Stimson, Blake (eds.) (2009). Institutional Critique: An Anthology of Artists’ Writings. Cambridge MA and London: The MIT Press, pp. 20-42.

VERWOERT, Jan. (2006). «This is Not an Exhibition» in Möntmann, Nina (ed.). Art and its Institutions: Current conflicts, critique and collaborations. London: Black Dog Publishing.