GAP AS A METAPHOR

Vasco Santos

1.

I have two impossible jobs. More: a kind of professional bisexuality: among psychoanalysts some people see me as an publisher. Among publishers other people seem me as a psychoanalyst. Which is more or less like this: «Oh! So you are Persian! What an amazing thing! How can one be Persian?»

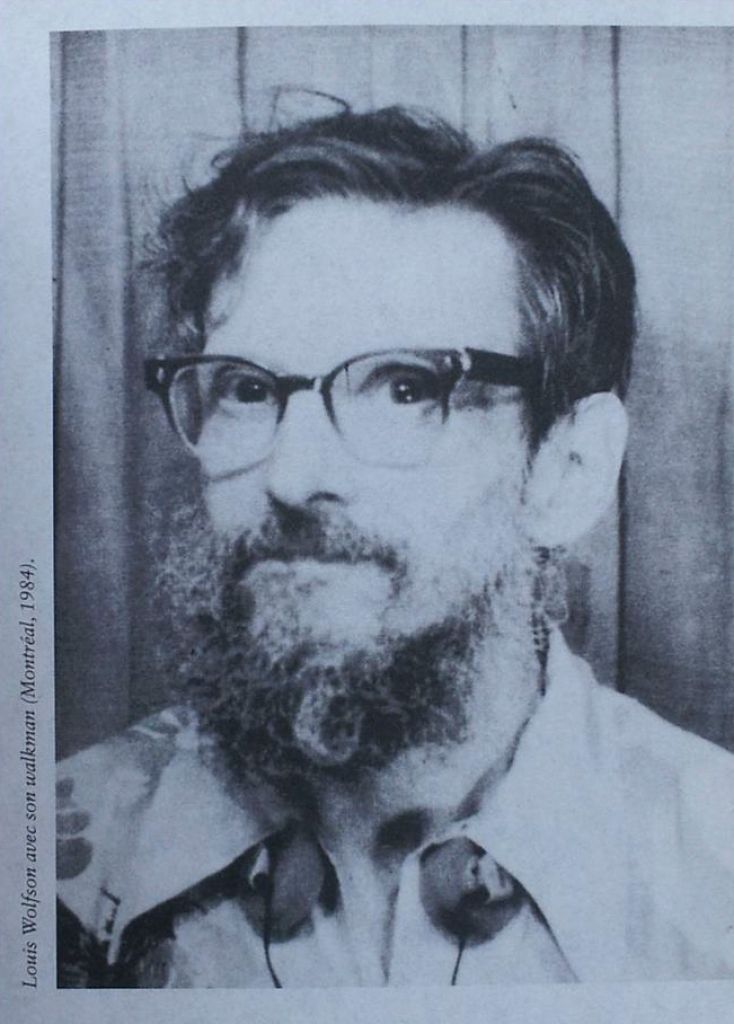

I edited Lautréamont, Raymond Roussel, Artaud, Henri Michaux, Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio. And J-B. Pontalis, which is one of the psychoanalysts with whom I identify more and which, was, also, editor at Gallimard. By free association I remembered to evoke Louis Wolfson (who sadly I didn’t edit).

In 1963 Pontalis received a manuscript with the title: Le Schizo et les langues ou La Phonétique chez le psychotique and a subtitle: Esquisses d’un étudiant de langues schizofrénique by Louis Wolfson, New Yorker, but written in French.

The book ends – after many dares – being published as part of Gallimard’s collection «Conaissance de l’inconscient», directed by Pontalis. The preface is Gilles Deleuze’s and is entitled Schizologie[1]. Deleuze was the first to get interested by Wolfson and, after the pre-publishing of eighty pages in Temps Modernes magazine, writes an article «Le Schizophrène et le mot» in Critique magazine (1968), dedicated to Artaud and to Lewis Carroll, but referencing Wolfson.

By its edition Alain Rey writes, also in Critique: «not only Wolfson’s text represents to the psychologist the equivalent to the notorious President Schreber’s Memoirs of my Nervous Illness but also is an indispensable reference – and dangerous – for the work concerning the Word, of the most privileged of the signs»[2].

In this regard Le Clézio wonders how can Wolfson’s book be read in a way, other than a medical document.

And his answer is admirable: «What is more distressing is not the psychologic or the pathologic case. Nothing is more reassuring than the mental illness or the social illness: they are curable. But here all balance laws are disrupted. We know immediately that there isn’t any qualitative difference between us and the famous young schizophrenic ‘lad’».

And adds: «what throws us deeply into Wolfson’s book is that he evokes a drama that we know so well and which we would like to forget: the drama of passage, or path, of language».

We will have two literatures then: the one from men who know how to talk and the one of men that didn’t learn how to talk.

2.

And it’s here that, evoking Pontalis, I would like to say something connected with Psychoanalysis. The psychoanalyst speech locates in «between-two», i.e., in the gap: «within the ones that feed his thought» – and more than authors are first his own patients – «and what can be emanate from his inner self: between the theory and the ghost, between knowledge and ignorance.»

In the image of the analyst inherited from Freud it seems to combine the ones of a decoder, of a detective and of an archeologist. This is: the analyst as master of significant.

Psychoanalysis would be thus one conceptual archeology exploring and precising the ghost’s status, of its origin, and what maintains its elective connection with sexuality and Oedipus complex.

It’s in the speech field, as Lacan taught, that analytical experience develops and, in that field’s core, what comes to light is another language more, dissociated from common language and which offers to decipher through those senses effects.

Psychoanalysis is, thus, a philosophy of the unconscious desire.

But we can discuss another perspective further, the one that is interested on the time when we were infants and we didn’t talk yet. A paradise lost of preconceptions. It’s a time without time, another world, the one of silence. And how can the passage be done to language, irreversible passage that we don’t know anything about and from which we cannot go back anymore?

A psychoanalysis as this demands a multi-focal vision, one ability of being continent, patience, and keep knowledge and no-knowledge, intuition, i.e., looking inside, listening not only the words and sounds but also the music.

Le Clézio (still regarding Wolfson and the gap that separates the work from silence) stands «around us that mute world exists and we recognize its presence: the one of objects, of animals and of infants. We are continually touched by its signs, summoned to answer it.

But we don’t understand anything of those signs, once that it’s through the word which has meaning and not for themselves».

A psychoanalysis as thus, demands, of course, as a literature, one war declaration to language limitations.

Then Eugenio Montale’s poem, The Shape of the World:

«If the world has the structure of language

and language the shape of mind

the mind with its fulls and empties

it’s nothing or barely and doesn’t reassures us.

And thus Papirio spoke. It was already dark

and raining. Let’s go to a safe place

said and accelerated the pace without acknowledging

that the language of delirium was speaking».

Psychoanalysis is one archeology, yes, but one archeology made in the present.

—

References

J-B. Pontalis. (2009). Dossier Wolfson ou L’Affaire Du Schizo et Les Langues. Paris: Gallimard.

J-B. Pontalis. (1999). Entre o Sonho e a Dor. Lisboa: Fenda.

Montesquieu. (1991). Cartas Persas. S. Paulo: Paulicéia.

Gilles Deleuze. (2000). Crítica e Clínica, Lisboa: Século XXI.

Sousa Dias. (1984). Questão de Estilo, Arte e Filosofia. Coimbra: Pé de Página.

Paul Ricoeur. (s/d). O Conflito das Interpretações. Porto: Rés.

Eugénio Montale. (2004). Poesia. Lisboa: Assírio & Alvim.

Footnotes

- ^ Here, I’m not going to develop and exemplify Wolfson’s general procedure in this work and in his second book (Ma mére musicienne est morte). In brief: the author is American, and his mother language is English but his books are written in French. The work of the «scholar of demented languages» is translating under given rules: has been given one word belonging to the mother language, one must search for a foreign word of identical meaning, but with common sounds or phonemes. The preferred and studied languages are French, German, Russian and Hebrew.

- ^ Regarding this subject see also Michel Foucault’s «The Escape/Disruption of ideas» where he analyses the three processes of R. Roussel, Louis Wolfson and Jean-Pierre Brisset. In the three cases is taken from the mother language a kind of foreign language, with the condition that the sounds or phonemes stay always similar. And also, within others, Paul Auster’s New York Babel, which is presented in the book/folder, dedicated to the subject and organized by J-B. Pontalis. Or also, the psychoanalytical interpretation of Piera Castoriadis - Aulagnier.