when the tip of my tongue came close to the screen

I would feel a tickling like the buzz of tiny bees

then the smell would invade both nose and brain

with its thick, unstable and metallic breath

the sound of the delicate touch

of the wet and slack muscle

eager to lick the glass made out of video

was carved as an erotic trigger

as I came closer and would approach my arm

my thin little hairs, instantly attracted,

would strait up and turn to it as fuck

like a mane on fire that would oscillate forever

this happened with this one tv only

small and grey with curved black borders

I remember your smells, your taste and how it felt

broadcasting emissions, whichever they may be

The British director Alan Clarke (1935 – 1990) developed a highly engaged body of work for television, addressing the political issues of his time with tireless attention to the systemic impacts of institutional power. What makes his work so unique nowadays is that he achieved it within the framework of national public television – the BBC – over the course of more than two decades. From my perspective, he achieved to express the harsh balance between codependency and autonomy – or, in other words, he explored the very fabric of society.

After completing National Service in Hong Kong, Clarke emigrated to Canada in 1957, where he worked in mining. Due to an injury, he ended up studying radio and television at Toronto’s Ryerson Institute of Technology. Upon returning to the UK, he worked for ATV and Rediffusion, honing his skills as a crew and actor manager, while also being involved in an amateur theatre company as both an actor and director. By the end of the 1960s, he began working for the BBC, where he would spend his entire career. Working for a major national TV network was undoubtedly the reason he made so many films (close to 60), with only 3 having cinema distribution – one of which was a remake of SCUM, after his original TV version had been censored.

His background in theater fostered a deep relationship with the flow of acting. The structure of the BBC provided a solid team of writers and technicians. The relatively low budgets and tight timelines (due to the demands of television broadcasting, as opposed to the cinema industry) are relevant aspects of his career as they had a profound impact on his working habits.

Like his peers, Stephen Frears and Ken Loach, Clarke’s work is intensely political and rooted in social realism. Although he experimented with different genres – drama, fantasy, comedy, dystopia – he always embedded his lexicon within the UK’s territory and the political fiasco of his time. Raising up issues such as racism, the collapse of social care, unemployment, the failures of inclusion, sexual abuses and drug addiction. His work focuses on the dysfunctions of institutions and their role in amplifying violence in society. Doing so from a massive institution itself, the BBC.

If one can identify quickly Alan Clarke’s spectrum range of interests, his formal style became instantly recognizable from the moment he began working with the Steadicam. Almost like an inversion of polarities, he transformed the performativity of speech and montage into a form of scopic performativity, which I will call here the «drone». Over time, his work will shape shift from the flow of substantial blocks of texts to long mute shots of walkers drifting in soured British suburbs.

In these walks, the gaze is stretched to a mechanical level – an open eye with no eyelid to close. Never blinks, only lingers. What sets it apart from the Steadicam or drone shots we mostly experience today – seen as omniscient and disembodied – is its sensitive engagement. That kind of shooting requires strong teamwork, synchronization, and unwavering focus. It’s a work of acute attention, where machines and bodies function as a single organ, confronting the inexorable flux of events. He never aimed for intangible shots, favouring on the contrary a one to one relation. You can feel a group at work to capture this vision, making it a pretty embodied vision.

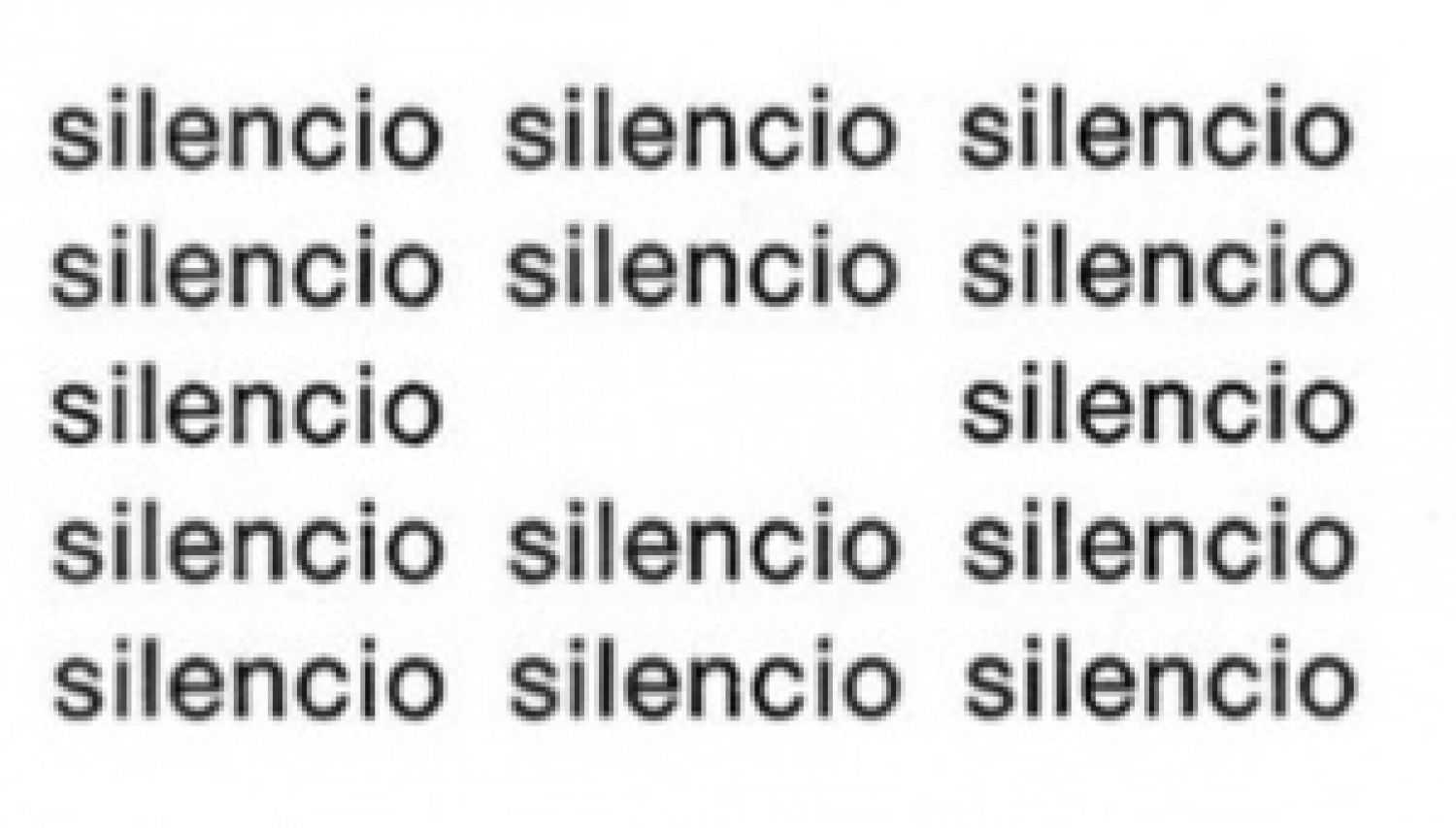

So, when I refer to the use of Steadicam as a «drone» I do so as an analogy to music which I will explain now.

A drone is a continuous low humming sound. Some instruments, like the bagpipes, tanpuras, Tibetan bowls or didgeridoos, can produce strict drones. Basically, they result from the emphasis and sustain of sounds, notes, or tones. They present little harmonic variation and they are rhythmically still or very slow. They are present in the traditional music of many parts of the world, but in Western music, they were particularly explored in the 1960s by minimalist and spectral composers like La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela or Éliane Radigue. The development of electronic instruments, such as synthesizers, greatly supported their use. Soon, they were incorporated into various genres, such as rock, ambient, experimental, metal, noise and electronic music. But what effect does a drone produce?

Due to the near absence of harmonic variation and rhythm, drone music tends to place the listener in an immersive, almost meditative state. While pop music could be thought of as a succession of accidents and patterns, drone music consists of suspended modulations. It works somewhat like a zoom into a specific sound that is sustained or repeated in a continuous fade. As a result, time feels stretched to its limits underlining the present moment and therefore disturbing its flow. It is an experience of perceptibility. To quote the researcher and journalist Manon Schaefle[1] about a conference of philosopher Catherine Guesde (specialist of radical music) entitled Excess and immersion in music: shipwreck with listener :

«The drone requires the public to put itself in a position of observation. [...] We have to get rid of our prior expectations, cease all activity, and place ourselves in a pure present. [...] Continuous sound requires us to be attentive to all auditory perceptions, such as textures, frequencies and power, and to the effects they have on us. [...] Like a living organism, the drone unfolds on its own, depending on how the external environment interacts with it. It's a philosophy of laissez-vivre.»

I spent years trying to pinspot what was exactly tickling my guts in Alan Clark’s movies. I think it is to be found on its equivalence in the sound field. It has something of a minimal intervention that allows the proper material and its components to unfold and expand. In my own practice, I also tend to work with materials that have a tendency to exceed themselves. I position myself within the chain of events, giving room for other elements to manifest their prior and forthcoming states. It has to do with a certain perspective on liberty that contaminates hopefully the viewer/listener, acknowledging their own abilities.

The broadcasting itself continues this idea of sustain even though it was only in the early 90s that channels started to emit 24 hours a day. TV and radio carried the promise of a constant connexion and frequencies reached directly the intimacy of the public. By default, it used to occur in a shared moment of time. Every single viewer was instantly immersed in an informal community of co-watchers.

In 1964 the Canadian philosopher Marshall McLuhan published his best-known theory about media Understanding Media: the extension of man in which he claims that «the media is the message». He would describe the «content» of a medium «as a juicy piece of meat carried by the burglar to distract the watchdog of the mind.» meaning that we would have the tendency to focus on the information passed through a communication forgetting that the way it is address is highly significant, if not more.

Kill the messenger?

Still in the UK, the 70’s and 80’s are marked by the productions of experimental and subversive artists Cosey Fanni Tutti, Genesis P-Orrige, Alex Fergusson, Chris Carter, Peter Christopherson and John Balance. They worked together in various combinations, forming multiple groups that blurred the lines between music, image, film, and performance. Amusingly, the names of their projects often referred to broadcasting, frequencies, or vibrations: COUM Transmission, Throbbing Gristle, Alternative TV, Psychic TV and Coil. They approached music as sound collage. Cosey Fanni Tutti mentioned her use of the guitar as a sound generator, which she could mess up with effect units. They began using the Roland TR-808 sequencer (some years before the emergence of acid music in the USA), injecting electronic elements into their nascent industrial music. Every tool was useful to elaborate cross-mixed performances and gigs dealing greatly with pornography and reflecting the still very coercitive society they lived in. Tutti describes the 1960s as liberal and the 1970s as an era of double standards: the sex industry was booming, yet consumers were being prosecuted and imprisoned[2]. In 1976, during the one-week exhibition of COUM Transmissions at the ICA, titled Pornography, the director's speech was replaced by a stripper performance, and wine was substituted with beer. The show featured bloody objects, jars of vaseline, rusty knives, photographic collages, performances presenting explicit sexual activity and the official launch of Throbbing Gristle with their third concert. Cosey Fanni Tutti’s work inside the pornographic industry was described by Gallien Déjean[3] as paradoxal «revealing the archetypes and normativity of the patriarchal fantasies produced by the capitalist industry and, like a mirror, turning the desiring gaze back onto itself.» The ICA’s exhibition sparked a massive media uproar and even led to a debate in Parliament about the future of 'Contemporary Art' in Great Britain. They’ve been commented as «the wreckers of civilization» to what Tutti would respond in these terms :

«My projects are presented unaltered in a very clinical way, as any other COUM project would be. The only difference is that my projects involve the very emotional ritual of making love. To make an action I must feel that the action is me and no one else, no influences, just purely me. This is where the photos and film come in… My actions are myself and not a projected character for people’s entertainment. When I am gone, they are yours.»[4]

Embodied to the bone. The mid-70s in the UK were marked by an urgent need to unload all types of energy, both individual and collective. Society was burnt out by the rise of the National Front and the radicalization of Conservative discourse.

In 1984, Alan Clarke’s Stars of the Roller State Disco depicts a group of teenagers skating within the huis clos of a discotheque. Almost as a redundancy, the camera movements accompany their circling around the track in an odd waltz. This dystopian work, written by Michael Hastings, set up the kids in a roller disco that turns out to be a jobcentre. They won’t get out of there until they’ll accept one of the underpaid opportunity the social workers offers them from behind the thick glass windows of their counters displayed around the track. The epicenter of the track is provided with three-tier bunk beds while its surrounding is filled up with vending machines, workshops and lavatories. We follow a young man in particular who’s girlfriend tries to convince him to accept anything to finally go out and on with their life. The kid sticks to the illusion that the government will provide him with the perfect work. Music and light shows goes on and on until curfew, everyday.

Each time I wake up

Each time I say

The shifting slow beginning

Another restless day

Doubt and indecision

Push me on my way

The shifting slow beginning

Another restless day

Supermarket Sunday

Faces cold and grey

No bread or milk or tea left

No energy to play

Fear is the jailer

That locks my love away

The boy on the checkout

Says «Have a restless day»

Who has the nerve

To dream, create and kill?

While it seems the whole moves

Every part stands still

So there's nothing, yes, there's nothing

Everything makes me ill

While it seems the whole moves

Every part stands still

Every part stands still

Watching television in the afternoon

Wasting my life away

All they want to show me is

What's under the clock today

But even rats in a cage

Are liable to stray[5]

Clarke's career was cut short when he died at the age of 55. Over the years, he portrayed a wide range of characters – teenagers, misfits, the elderly, social workers, criminals, the disabled, mystics, racists, the unemployed, drug addicts, and soccer hooligans – with the same care. His penultimate film, Elephant, aired in 1989, was commissioned to him to reflect on the crimes happening in Belfast. It became, alongside Christine[6], one of his most radical, provocative, and almost conceptual works. A 38 minutes long film made of 18 Steadicam shots, each showing a person or two arriving at a location, committing a killing and leaving. A totally un-contextualized object showing objective killings.

Facing objections to his treatment of violence on screen, he responded by pointing out the necessity of being honest about violence, showing the violence being violence, neither trying to diminish it, nor explore it with some close ups or music that could turn it somehow admirable.

The earth is full of ghosts now

Ghosts that sweat and ghosts that cry

Instead of peace just stop and cease

A final end, a sweet release

The shipwreck to the shore

From the client to the whore

From the shadow to the sun

From the bullet to the gun

The earth is full of ghosts now

Ghosts that sweat and ghosts that cry

Instead of peace just stop and cease

A final end, a sweet release[7]

Nowadays, channels are still battling for frequencies, even though the connections through fiber optic cables and satellites are competing with traditional Hertzian systems. Aside from political announcements and sports events, real-time broadcasting is weakening, while à la carte options tend to be privileged. At the same time, the numerous 24/7 news channels cycle through the flow of information at the speed of imprecision we know all too well.

Everything about COUM is true. Everything about COUM is false[8]

The true is a moment of the false[9]; our thirst to capture authenticity through representation will never stop unless we’ll get satiated with the filtered news of some algorithm… until the dysentery strikes.

Granted disappointment.[10]

Footnotes