CORPO MANIFESTAÇÃO – SMALL LEXICON ABOUT THE HISTORY OF PERFORMANCE IN PORTUGAL – Episode 2: PARTICIPATION

Paula Pinto

How does the female body, shut in its invisibility, moulded to please the male gaze, become visible when changing its social and public interaction in a political environment? Performance allowed the creation of this deviation, bringing to the space of manifestation/demonstration acts and gestures loaded with values and meanings imposed, for centuries, on female bodies, knowledge and behaviours.

In a country with a dictatorship that lasted nearly half a century, in which citizens were denied the possibility of expressing themselves, were forced to take part in a war they did not believe, and witnessed the loss, made invisible, of their closest loved ones, many felt compelled to leave the country, on grants from the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation or simply by fleeing, clandestinely, as emigrants. Artists like Brazilian Irene Buarque, who arrived in Portugal in 1973, testify to the absence of male bodies in the country. As in any situation of dictatorship and war, many women used their invisibility to protect themselves, others to fight in hiding, others still, on the contrary, denouncing the imposed situation, explicitly and directly, in literary, artistic and other struggles.

Disinvestment in education and in social and human mindfulness and cultural censorship had overwhelming effects on the Portuguese population, with greater expression outside the urban centers, more privileged in every way. Some gallerists, such as Jaime Isidoro and the art critic Egídio Álvaro, sought to play a role in the decentralization of the arts, during and after the end of the dictatorship, even allowing the contact of populations in the interior lands with works and actions by international artists. After decades of painstaking scenography of the «most Portuguese villages of Portugal», this international opening was made together with the populations, trying to merge creation and observation from a distance, body and work, manifestation and demonstration: the rallying cry became PARTICIPATION. Immediately after the 1974 revolution, many foreigners, curiously and genuinely, sought to participate in the «International Art Meetings in Portugal». In the British magazine New Society[1], journalist Angela Carter wrote: «So I was curious and excited about the things that might happen in a country where the virus of modern art has been isolated in quarantine wards in Lisbon and Oporto or sent off to Paris with a grant.»[2]

Fifty years after 1974, from the documentation of the artistic proposals presented at the International Art Meetings in Portugal (1974-1977), it is noticeable that artistic performance is directly inscribed in the sociocultural context of its era, that is, to activate the body as an artistic tool in a specific urban context, in this case politically and culturally decentralised, does not carry the same meaning nor results in an equivalent way to the presentation of performances in museum contexts, in spite of both being ephemeral and unrepeatable actions, relying on the audience. In the field of artistic performance, experiencing, watching and participating happen in symbiosis, in a unique same moment, resulting in a joint action, but presenting oneself in front of an audience that came on purpose to watch an artistic expression in a daily context foreign to any artistic practice, and presenting oneself in front of different audiences, adds social and political value to the manifestation. The migration of artistic performance experiences developed in an international context to the politically and culturally decentralised territory of the post-revolutionary period, a purpose undertaken by the International Art Meetings in Portugal, allowed triggering experiences in unknown social contexts. Without speaking or understanding the Portuguese language, some artists performed individually, their bodies the sole intermediary of communication; by contrast, they met an unprepared population, never before exposed to contemporary artistic interventions, particularly to explicit nudity (or its image) in public, and still devoid of tools to make sense of, or integrate, the proposed experiences.

Although all the international artists who arrived in Caldas da Rainha in 1977 expressed their surprise at the eccentricity and explicit sexuality of the «folk tableware» that is specific to the region, any jokeless allusion to the morally called «pornography» was excluded from the agency of women, children and the popular classes. When in 1965 the publishing house Afrodite released the Anthology of Erotic and Satirical Portuguese Poetry, political censorship did not forgive that the merit of bringing together the work’s multiple authors (who ranged from the 13th century to contemporary times) and the authorship of the preface belonged to a woman. As described in Natália Correia's biography, «for the first time, a prosecutor from the Public Ministry had to transcribe into the records the words ´cunt´, ´slit´, ´ass´, ´shiter´, ´prick´, ´shlong´, ´prick show´, ´spunk´, ´hyperspunk´, ´cock´, ´dick´, ´big willy´, ´bollocks´, ´bush´, ´fuck´, ´shag´, ´cum´, ´chow´, ´cuckold´, ´whore´, extracted from the compiled verses. Quod erat demonstrandum, they served to illustrate the ´pornographic, vile, obscene character of the book, capable of offending general modesty, public decency, good customs, sexual modesty, morality´, ´even denoting an outrageous purpose´.»

The indictment reads:

«The publication of the aforementioned book is a malicious undertaking by all the accused, chiefly Natália Correia and Bento de Melo, with the sole intention of exploiting demoralisation (of youth particularly) under the guise of freedom advocacy, good faith, clear conscience, culture, scholarship and civility».[3]

As the crime of abuse of press freedom was directly related to its distribution and public access, the talk «of modesty, good customs and public decency» and the arguments of immorality disguised as erudition and culture became viscerally and violently ingrained in a persecuted and censored population, which for nearly half a century, the Portuguese dictatorship condemned to blindness and invisibility.

In the «Pre-Preface» of New Portuguese Letters, Maria de Lourdes Pintasilgo writes about this book collectively undertaken by Maria Isabel Barreno, Maria Teresa Horta and Maria Velho da Costa:

«They burst, therefore they overflow. (...) In this excess (...) lies, ultimately, the great ambiguity that caused the boundaries between eroticism and pornography to be arguably crossed. (...) there’s the audacity of women breaking the limits, upending the universally accepted subject/object situation. By seizing situations hitherto only spoken by men, the authors actually 'kill' someone: they kill the ghost of the man-master that hovers in the affective horizon of women. And they kill it with the very weapons that the man uses to dominate the woman (...), In this excess (...) women take pleasure in themselves, their passion feeds on itself. Hence the obsessive claim to the body as the first battlefield where revolt manifests itself.

(...) the body, as the preferred place for denouncing the oppression of women, exceeds itself in what it represents. It works as a metaphor for all veiled and not yet conquered forms of oppression.»[4]

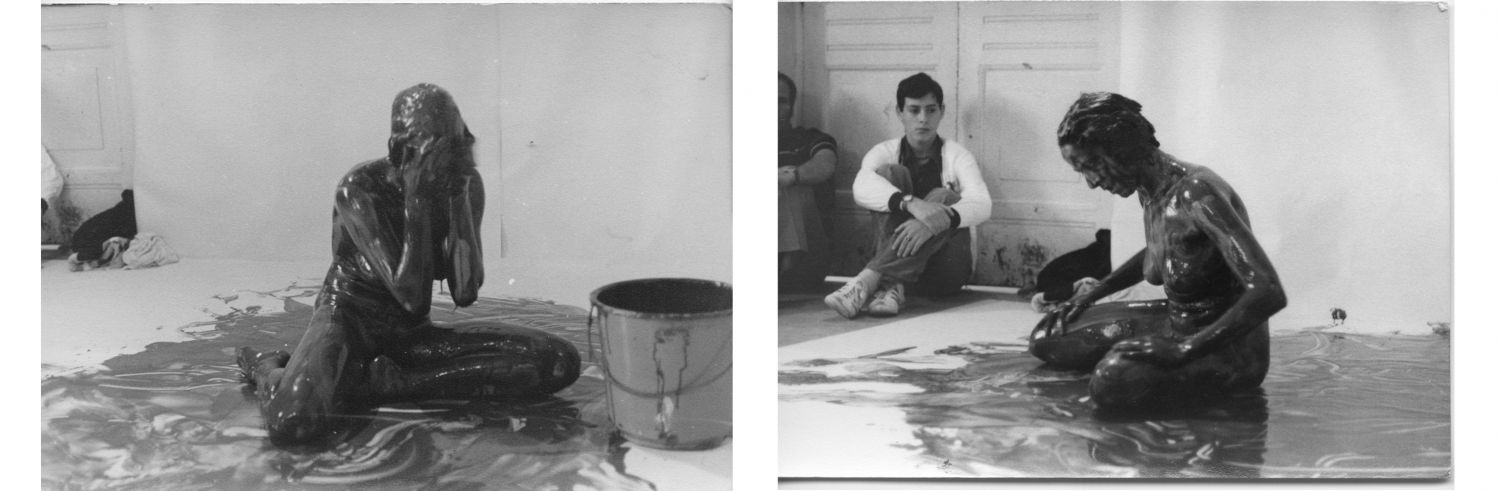

On August 9, 1977, at the IV International Art Meetings, the artist Chantal Guyot presented a «bodily action» at the Casa da Cultura, in Caldas da Rainha. In Performance, rituels et interventions en espace urbain, art du comportement au Portugal (1979), Egídio Álvaro described the performance:

«Chantal Guyot, in a gesture of protest, takes off her clothes in front of a sexist audience ready to boo her and, in total silence, soaks her body in liquid chocolate and slithes, becoming a living statue, leaving the traces of her movement in the paper that covers the walls and floor».

Contrary to what Yves Klein had previously done in March 1960, – with his Anthropométries de l'époque bleue, orchestrating female models who impregnated their naked bodies with blue paint and acted like human paintbrushes to the sound of a male orchestra playing for a bourgeois audience at the Galerie Internationale d'Art Contemporain (Paris) –, in 1977 Chantal Guyot assumed herself as the author of the performance, which by using her most private domain, her own body, exposed it denouncing the sexist gaze, through the pleasure that the experience provided. While Klein, dressed in a tuxedo, presents an unidentified sequence of models, who paint and stamp themselves following verbal instructions from the artist (who never actually touches the paint), Guyot, instead of presenting herself as just another body, publicly assumes the authorship of the performance and ends up representing the female body as a collective. Ironically, Chantal Guyot's work does not seem to have lingered in the History of Art.[5]

In Colóquio Artes magazine, Eurico Gonçalves wrote: «(...) when Chantal Guyot covered the nakedness of her body with (...) chocolate, there were those who interpreted this as pure aesthetic action, and there were those, more shocked, who invoked the so-called 'offense to public morals’.»[6]

In a video documentary filmed by Swiss photographer Ursula Zangger, it is possible to hear a conversation in the background, where a woman who grows uncomfortable with Guyot's actions is confronted with aesthetic arguments involving the existence of female statues in parks, and ends up recognising that the artist has a beautiful body and that chocolate has a beautifying and sculptural role in her action. In a sort of updated Pygmalion myth, the statue not only comes to life but also emancipates herself from the sculptor, with the audience playing a determining role in its liberation.

Even so, a popular rebellion ended up violently destroying a series of works, such as the Monument to March 16, 1974,[7] built by Grupo Acre in a city square, or a work by Grupo Puzzle, cemented in the garden of the José Malhoa Museum[8]. Many artists felt verbally and physically intimidated and were forced to take cover and disappear from the city. In another video from the International Art Meetings, one can witness artist Túlia Saldanha's attempt at dialogue with a population asking for clarification, while a group of men just try to stir up tempers, without any willingness to listen or ability to argue. At the beginning of the video, a man throws into the discussion: «They say there was a woman there smeared in cocoa, or whatever it was!»

The locals complained about the artists receiving money from the Portuguese State while the people were hungry and expressed disapproval on the arrival of foreign artists to damage public morals and local customs. Túlia Saldanha questions them directly about the whirlwind of pornographic films that invaded cinemas after the Revolution, without these men feeling uncomfortable or outraged with the display of naked female bodies and explicit acts of sexual exploitation on the big screen. But the tone of the responses is exceedingly aggressive and their attitudes exceedingly cowardly: they say they feel deceived by the fact that «parasites» have subsidies for immoral behaviour; even without real knowledge of the facts, they feel entitled to substantiate their accusations. It was the instigation of hatred that left the artists and their works unprotected and subjected to misconstructions, especially after the City Council and political parties dissociated themselves from the organisation of the Meetings and regretted what happened. The verbal attacks increased in tone and spread among the population of Caldas, undoing all the positive experiences lived in those days, and unveiling the profound discrepancy with the young democracy, which at the time would solely boost itself culturally in the capital and in intellectually and artistically exclusive contexts. The violence of these very sporadic and easy-to-identify actions only revealed the inability to accept freedom, most particularly female freedom.

Not knowing how to take advantage of the confrontation to debate ideas, but taking advantage of the sensationalism of the «worst» that had happened at the Meetings – of which the worst was in reality the popular uprising against the artists and their works –, the newspapers ended up giving more space to letters from readers extolling the «good old customs», instead of informing or trying to critically analyse the events.

As an exception, Eurico Gonçalves’s articles[9] stand out, in which he contextualized the event as a meeting between artists and local populations ignorant of each other, which consequently led to clashes of attitudes, ideas and opinions, yet defending the benefit of the controversy for all the agents involved. Among other things, this benefit comprised access to dialogue, freedom of expression and creativity, the extrication of Portuguese art from its state of isolation, and the opportunity for national artists’ experimental work to mature. The author also mentions the need to demystify established values inside and outside art, to create art pedagogies, and new behaviours and ways of seeing and being in the world. Eurico Gonçalves points out the need for the Meetings to be better prepared and more attentive to the sociocultural characteristics of the locations where they take place, but chastises the policing of the artists' intervention activities, as was demanded by the most reactionary voices. Not disregarding his own role, he draws the attention of artists and intellectuals to the cultural responsibility of contributing to the country's cultural revolution.

It should be stressed that the decentralisation policy of the Meetings escaped the generalised control of the means of cultural production in Portugal and that artists were granted full freedom of expression. Following the work of British artists Shirley Cameron and Roland Miller, and trying to summarise the twelve days of activities in Caldas da Rainha, the writer Angela Carter wrote: «In a country where bread is scarce, we must feed the birds with discretion»[10]. And she explains that in a new democracy where the possibilities of desiring, imagining and dreaming – the domains of art – may seem to harm the reality of its inhabitants, it is necessary to distribute them carefully. In reality, it was the local mentalities themselves that were exposed by the conflict, and as long as their discourse prevail over everything that was achieved in Caldas da Rainha, our future will continue to be compromised by the past.

Carter also wrote: «A country man was asked to get off his donkey to in order to help ruining a street demonstration that was taking place. Smiling with the full width of his decayed teeth, he replied: 'If my rheumatism would let me, I would rather dance with them!’»[11] It is necessary to understand that the PARTY has no spectators, happy or displeased, but that those who participate are the ones who make the PARTY. For better or worse, there is no transformation without participation. Just as one is never a spectator in a war, whoever wanted to see revolution happening participated in it. If «the [female] body is the battlefield where revolt manifests»[12], what these documents make visible is that it is the participants, consciously or unconsciously, who allow the performance to happen. It is this deviation that performance activates, as an instrument of social interaction, and whose political environment allowed women to exit the condition in which they were confined, to manifest/demonstrate the transition from object to subject, which explains the importance of these artistic undertakings in the pathways of many women.

Paula Pinto, October 2024

Footnotes

- ^ New Society was a weekly magazine of social research and social and cultural commentary, published in the United Kingdom from 1962 to 1988. It published articles relating to the disciplines of sociology, anthropology, psychology, human geography, social history and social policy, and a wide range of comprehensive social reportage. In contrast to other London-based opinion magazines, New Society's emphasis was strongly non-metropolitan, preferring to focus on «Other Britain».

- ^ Angela Carter, «Bread on Still Waters», New Society, October 13, 1977; reprinted in Shaking a Leg: Collected Journalism, London: Chatto & Windus, 1997, pp. 167-170.

- ^ Filipa Martins, «O Cativeiro de Afrodite» in O Dever de Deslumbrar. Biografia de Natália Correia, Lisboa, Contraponto, 2023, pp.250-274.

- ^ Maria de Lourdes Pintasilgo, «Pré-Prefácio», in Maria Isabel Barreno, Maria Teresa Horta and Maria Velho da Costa, Novas Cartas Portuguesas, organised by Ana Luísa Amaral, Lisboa, D. Quixote, 2022 (annotated edition).

- ^ So far, I have not been able to identify the origin or whereabouts of Chantal Guyot, and I am unaware of any other works or performances that the artist has carried out before or after this «bodily action» in Caldas da Rainha.

- ^ Eurico Gonçalves, «IV Encontros Internacionais de Arte em Portugal», Colóquio Artes, N. 34, October 1977.

- ^ March 16, 1974 marks an attempted military coup against the regime in which only the 5th Infantry Regiment of Caldas da Rainha marched on Lisbon. The coup failed and as a result around 200 soldiers were arrested.

- ^ Christian Tobas also offered/implemented a work in the public space of Caldas da Rainha, whose destruction was not feasible: «After the [more ephemeral] experience of the Third Encounters, this year I hope to organise myself in a totally different way. I would like to carry out a work at the Meetings location itself. I think of a large stone sculpture. I’m preparing a small-scale model. The sculpture will be made in the garden. I would like to leave to the municipality that hosts the Meetings a sign/tribute to the courage of a poor country that does the work that richer and more developed countries do not do. Thus, leaving in Portugal the trace of our passage and our dialogue with the populations.» The aforementioned stones were found in Peniche and transported to Caldas da Rainha. See: «Quartos Encontros Internacionais de Arte em Portugal», Supplement to Gazeta das Caldas, July 29, 1977, p.6.

- ^ Eurico Gonçalves, «IV Encontros Internacionais de Arte em Portugal», in Colóquio Artes, N.34, October 1977, pp. 71-73.

- ^ ngela Carter, «Bread on Still Waters», New Society, October 13, 1977; reprinted in Shaking a Leg: Collected Journalism, London: Chatto & Windus, 1997, pp. 167-170.

- ^ Anonymous, «Com Saldo Positivo: Encontros Internacionais de Arte», in Diário de Notícias do Funchal, September 11, 1977.

- ^ Maria de Lourdes Pintasilgo, «Pré-Prefácio», in Maria Isabel Barreno, Maria Teresa Horta and Maria Velho da Costa, Novas Cartas Portuguesas, organised by Ana Luísa Amaral, Lisbon, D. Quixote, 2022 (annotated edition), p. XXVIII.