CORPO MANIFESTAÇÃO – SMALL LEXICON ABOUT THE HISTORY OF PERFORMANCE IN PORTUGAL – Episode 1: PLASTÍCIFES

Paula PintoLooking to answer the question «In which way performance art was important in the fight for emancipation, equal rights, liberties and justice of Portuguese women in the April’s 1974 revolution?», the project CORPO MANIFESTAÇÃO presents in WrongWrong´s currente issue, a set of performance art cases that were seminal for the conquest of democracy in Portugal.

Considered on the basis of different visual and media materials, most of which have been rehabilitated from the collection of art critic Egídio Álvaro, some of the examples presented here reflect a new field of artistic experimentation and political and cultural manifestation. The estate of Egídio Álvaro (Coimbra, 1937 – Montrouge, 2020), a cultural promotor that was particularly devoted to the performing arts and in building bridges between portuguese and international artists (living mostly in Paris), was recovered by the project Performing the Archive, in Paris, in August, 2021. And it is by activating this archive of visual and cultural materials dedicated to performance art, through numerous projects that we have developed with different researchers and artists, that we can reverse the invisibility to which these forms of public expression and manifestation have been condemned.

Until this moment, four exhibitions were organised: Lembrar o Futuro: Arquivo de Performances, (RAMPA, Porto, 21.04.–11.06.2022); Performances, Projecções, Debates e Redações, (RAMPA, (Porto, 26.07.– 14.09.2024);, ANDOR! Encontros, Manifestações de rua e Espaços Vivos (in the streets and library of Diana Bar, Póvoa de Varzim, 2 – 4.08.2024); Corpo Manifestação: Transmissões da Performance-Artes nos Feminismos em Portugal, (in the space of Performing the Archive, Porto, 22.09.–21.10.2024). Between viewing sessions of photographs and videos in analogue and digital format, the listening of sound recordings, to the presentation of original live performances and re-enactments of works documented in the collection, as also the creation of new works by visual artists made specifically for these programmes, graphic poster workshops, the organization of informal talks and recording interviews with performing artists, the production of historical works, public discussions, the loaning of materials and works, the hosting of artist residencies,meetings and research laboratories and the construction of the website www.performing thearchive.com.[1]

Recognizing, celebrating and activating the documentary archive of this art critic and promoter of performance art, opening it up to a community of artists, historians and others interested in the history of performance art, has made it possible both to debate and to renew the cultural approach to ephemeral materials and actions that, with the passage of time, need to be activated by new generations, to find new spaces and means of exhibition. The establishment of this network of projects has created multiple opportunities to think about and actively participate in the current state of the arts in Portugal. Over the time, it has become clear that, more than inscribing, the important thing has been to question the historical construction of the artistic past, and to make its mediatization available as a tool for future memory.

The dematerialization of the work of art, which led to the ephemerality of cultural events, has produced new encounters and new collisions between artists and audience, on a new and shared common ground for public reception. It was this context, between the uprising and the French revolt in May 1969, and the Portuguese revolution 1974 – where the cultural promoter Egídio Álvaro circulated – that lead the artists to the street, and therefore to a direct contact with much vaster audiences than the ones in museums and galleries.

Despite the wider socio-cultural disparities among the population, which reflected an alienation imposed by the authoritarian regime, these new sharing places highlighted the extreme availability for the establishing of intense and affective relationships between different groups.

An unknown future was being celebrated, but not without the cultural clashes created by the liberating slogan «forbidden to forbid»[2], some of which were caused by political exploitation and others rooted in religious moralism.

But the desire for a more shared future was evident in the transversal struggles for rights and freedom. And these political conquests were essential for defending transformations, rights and freedoms. The great manifestation of this freedom, which expanded the experience and made the expression of subjectivity more plural, was the body revolution. Inseparable from life, art began to incorporate the demand for gender equality and activated the female body in performance in a manifestly liberating way, simultaneously opening the way for non-binary forms of representation.

Egídio Álvaro followed the interest in the performance art of a series of female artists, in which the body manifested itself as an expression of existence and transformation. Examples include, among other female artists: Barbara Heinisch, Laurence Hardy, Gaël, Ilse Wegman-Hacker, Monique Hebré, Natascha Fiala, Suzanne Krist, Catherine Meziat, Chantal Guyot, the Rupture/ Enfermement collective – which included Colette Deblé, Danièle Boone, Claudette Brun, Françoise Eliet, Monique Fryman, Christina Mauric e Michèle Henry Marcelle –, Van Bemmel, Tara Babel, Lydia Schouten, Nil Yalter, Ção Pestana, Clara Menéres, Elisabeth Morcellet, ORLAN, Lidia Martinez, Eugenia Balcells, Gretta Sarfaty, Marie Kawazu, Lidia Martinez, Elisabete Mileu, Manuela Fortuna, Shirley Cameron, Ria Pacque, Sara Wiame, Túlia Saldanha, Flore Bury, Gina Pane, Silvia Kirchoff, Zoé Léonard, etc, etc… many of whom have traveled through Portugal and performed with portuguese artists across various territories.

Performance, and in parallel some media such as photography, video and television, enabled artists to explore contemporary time and space, without the mandatory subordination to patriarchal discourses or the need for cultural recognition imposed on any «original and acclaimed work of art», selected and exhibited in the controlled environment of museums. Given the ephemeral nature of performance-art, these new media were the ones that better enabled the real-time live transformations, simultaneously recording and transmitting new experiences. Photojournalists and the general public recorded and witnessed unprecedented situations, for which they did not have reading tools.

These photographs, although scattered and mostly missing, expand the memory of moments which apparently didn’t impact the public, but that effectively captured, without mercy, the social inability to accept freedom, apparently claimed by and for everyone. The writings which Egídio Álvaro published throughout his life, and the visual and sound recordings – contact sheets, slides, negatives, paper prints, images printed in publications, audio and video interviews – many of which are unknown to the performers themselves and to Portuguese Art History, highlight the performative journey of these artists and open up before us a long path of research and reflection about performance art, to be explored over the next three months, from Paris, for WrongWrong magazine.

- PLASTIFICE OR SCENIC SCULPTURES

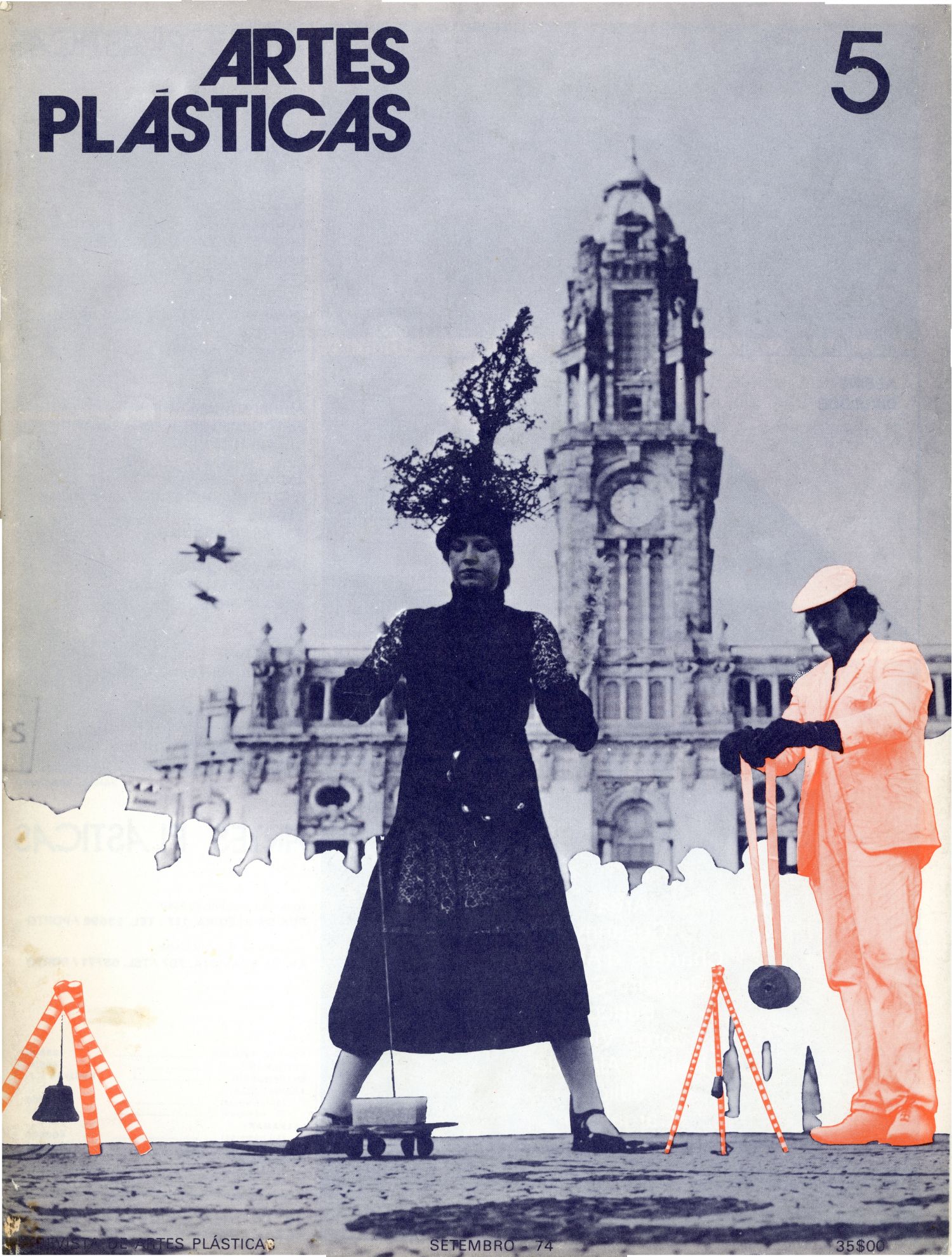

It was before the revolution of April 25th 1974, that the british artists Shirley Cameron and Rolland Miller created «scenic sculptures» in the Porto streets, invited by the art critic Egídio Álvaro and the gallerist Jaime Isidoro, during the international cycle PERSPECTIVA 74, organised by the Alvarez group. As the cover of Artes Plásticas (5th issue, September 1974) proves, Shirly Cameron was most probably one of the first women to intervene publicly the urban space[3], choosing Avenida dos Aliados, in front of Porto City Hall building, to get closer to a non-specialized public in the arts.

Sculpture student at St. Martin’s School between 1962 and 1966 (having as teachers Antony Caro and Phillip King and where, also during that time, Gilbert & George studied), Shirley Cameron, in 1970, began creating actions with her partner Rolland Miller, where they would mix the colourful and geometric forms of their sculptures with theatrical nonsense actions, inspired in the receptivity and popular participation of street «puppet shows», most notably known in Portugal as «fantoches» or «robertos».

An integral part of the 20th aniversary celebration of Galeria Dominguez Alvarez (opened by Jaime Isidoro in 1954), the International Cycle PERSPECTIVA 74, organised between February 16th and May 1st 1974, was dedicated to the art of process and intervention in the urban space, serving as programming rehearsal to the future International Art Encounters in Portugal[4]. Having coincided with the April 25th 1974, the PERSPECTIVA 74 cycle and weeks later, the organisation of the 1st International Encounters of Art in Portugal (Valadares), attracted foreign artists to our country and triggered invitations to Portuguese artists to exhibit abroad. Hosting international artists allowed to build a common field of work and experience.

Dominated by male artists (13 artists from six countries), this first international cycle counted, nevertheless with a feminine presence, Shirly Cameron, who, together with her partner Rolland Miller, created several performances/ installations, as for instance Pink & Black, in galeria Alvarez[5] and at least another action on Avenida dos Aliados, in front of Porto City Hall building, between March 9th and 16th 1974[6]. The British artists came into direct contact with an anonymous population, going to meet them in the city centre. And by the occasion of this last performance, one can read in Diário Popular[7]:

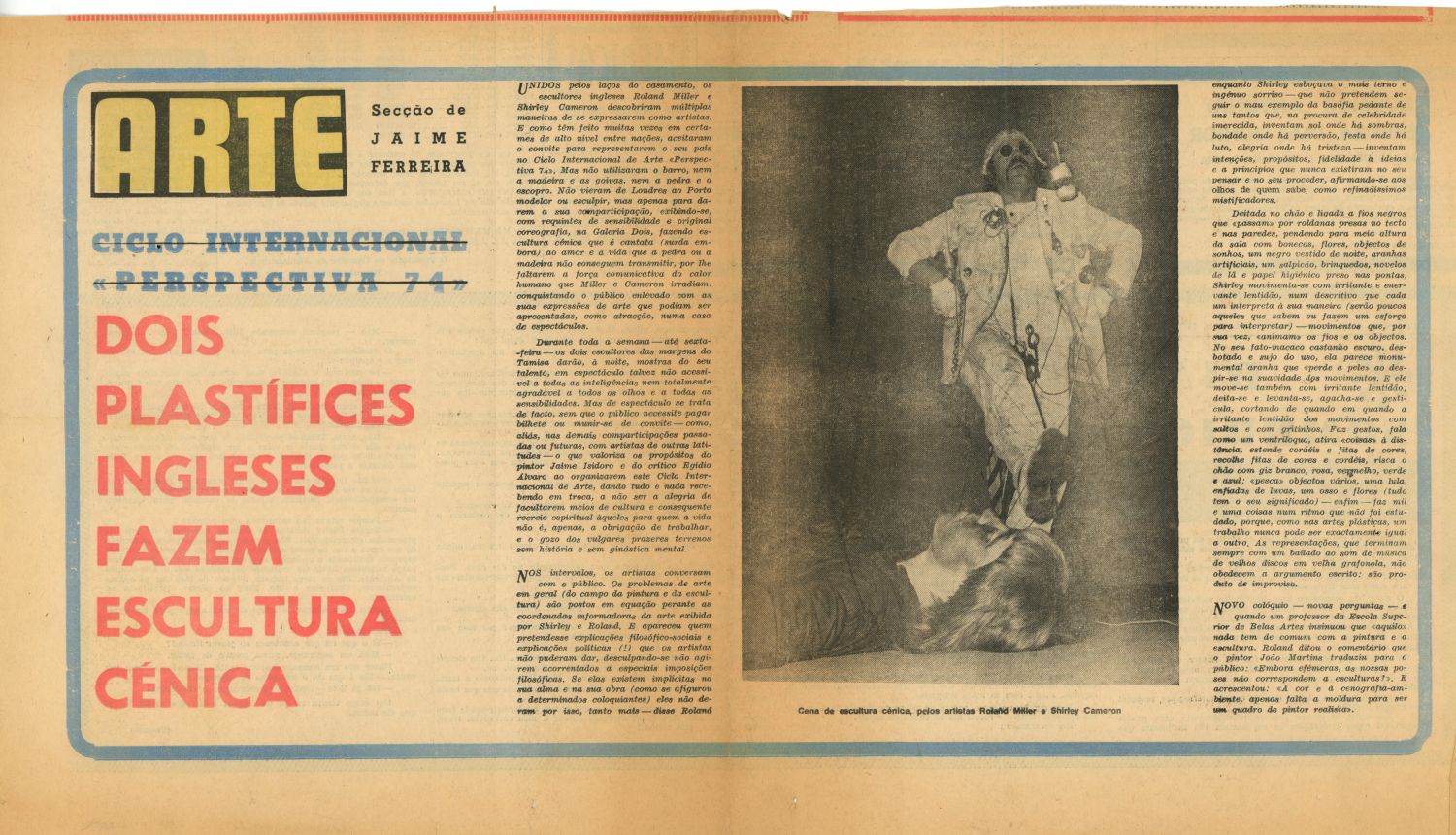

«The unusual and picturesque of the show and art came out onto the street to meet the public. It was this what happened, by the hands of English artists Shirley Cameron e Roland Miller (...)

She with an elegant black dress, of lace, length down to the feet (looking as a “twenties” figure), huge half-moons under the black shoes soles, flower arrangement (of salt water false willow) in her head, stuck by a string following her in her own rhythmic walk, caricatural of the life stages, one small cart in heart shape, with corn for the pigeons and sparrows. He dressed in a pink suit, exhibiting several props, ribbons also pink, and “rocked” when the church of a bell rang.

Never before had such a spectacle been seen in the city centre. And the artists, engulfed by the public who didn’t leave them free space to move, transmitted as they could, with some natural difficulties, their message that perhaps no one had understood. But the presence of Shirley and Miller, in the middle of the public square, resulted completely as a spectacle and communication with the public, although the younger kids shouted “look at them, they are promoting the circus”. But the two English artists' performance had nothing to do with clowning.(…)»[8]

According to the artists, identified in the same article as «scenic sculptures», their interventions had the intention of «giving to imagination a physical life inside the human body». Without access to the Portuguese language, the body of these artists claimed one life to be liberated through imagination. To do this, they went to the city center, meeting an unprepared public, who, allowing themselves to be driven by curiosity, «left them no free space to move around.»

The Diário Popular article in the rubric o Porto por telex, describes the passage of the artists, without the right for one single image to be printed, and the color, so expressively present in their performances, would still take some time to reach the daily press. Despite gallerists using photojournalists to document these actions, there was still no social awareness about visual illiteracy and its relationship with the dictatorship. Even without using verbal language, their bodies stood out and expressed freely. Despite the proximity to the announcement of other titles, such as «Vasarely exhibition opened yesterday at Quadrum[9]», the absence of images calmed curiosity down, cancelling any possibility of visual comparison between different expressions of artistic forms.

It is, however, the always excellent images by Jornal de Notícias photojournalist, António Pereira de Sousa, which, although in black and white, that still give us access to this imaginary performance, which only in that space and time became real. Despite the impact that the artists may have had, without access to these images, it is as if there were no testimonies. But the audience looks at performance and the camera looks back at them and fixes them in the quality of agents of their own time. Still without a lexicon to describe their actions, Jaime Ferreira, journalist of Comércio do Porto, who often reported activities of Alvarez gallery, signs an article with the tittle «Two British Plastifices do Scenic Sculpture»:

«(…) the sculptors (...) They didn’t come from London to Porto to model or sculpt, but to contribute, exhibiting themselves with exquisite sensitivity and original choreography(...), making scenic sculpture, which is sang (hard of hearing, though) dedicated to the love and to the life which neither stone or wood are able to transmit, for lacking the communicative force of human warmth that Miller and Cameron radiate. (...)

During the whole week, the two sculpture artists from the banks of Thames will give shows of their talent, in spectacles perhaps not accessible to all intelligences neither totally pleasant to all eyes and to all sensibilities, (...) without the need for the public to pay a ticket or having an invitation. (...)

During the intervals, the artists talk with the public. The problems of art in general (from the field of painting and sculpture) are put in equation towards the informing coordinates of the art exhibited by Shirley and Roland. (...)

(...) and when one teacher of the School of Fine Arts insinuates that ‘that’ [had] nothing to do with painting or sculpture, (...) the painter Jorge Martins translated to the audience: “Although they are ephemeral, don’t our poses correspond to sculptures?” and added: “To the colour and to the ambient-scenography, only the frame is missing so it can be considered a painting of a realist painter.”»[10]

In a declaration, under the title «Landscape and living spaces» (Grantham, 28.01.1974), the artists write:

«(…) We believe that the direct contact, personal, between artists and observers creates one additional possibility – more freedom for the perception and imagination of society. (...) The imaginative, mystic, magical/religious reserves are inexhaustible, but they can remain enclosed within people due to “civilizational” constraints. Our particular way of art expresses our desire of liberating these reserves and give them an active expression. We have a defined role, but through corporal expression our experiences open up to the participation of others; we have a personal way of expression within a communal activity. Inevitably, our work is out of step, in relationship with society, but we accept it as one formal condition, a dimension within which our image is located. The one and only aspiration of “Performance/art” is to give to imagination one physical life within the human body.»[11]

Shirley Cameron and Roland Miller came back several times to Portugal, performing in decentralised socio-cultural contexts, such as Póvoa de Varzim (1976) and Caldas da Rainha (1977) and followed the critic Egídio Álvaro in other international performance festivals, in different geographies. During the Portuguese post-revolutionary period, they gave their bodies to imagination, but as the British writer Angela Carter (1940-1992) wrote, who have followed them in 1977, at Caldas da Rainha, in a new democracy where the possibilities of desiring, imagining and dreaming look like they can hurt the reality of its inhabitants, it’s necessary to distribute freedom with care.

Footnotes

- ^ All this work was only possible to make with the support of: CRIATÓRIO da Ágora, Apoio da DGArtes: Programa de Apoio em Parceria – Arquivos de Dança, Teatro e Cruzamento Disciplinar, Apoio Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, Apoio Arte pela Democracia from Comissão Comemorativa dos 50 anos de Abril in partnership with D.G.Artes and InResidence, as well as with the generosity of Eliane Figueiredo and all artists and researchers involved in all projects.

- ^ N.T. – It’s forbidden to forbid.

- ^ N.T. – In Portugal and within an artistic context.

- ^ N.T. – Encontros Internacionais de Arte em Portugal.

- ^ One performance entitled with the same name, Pink & Black, had already been presented at Open Festival, Louvain, Belgium in 1973.

- ^ In 1973 Shirley Cameron and Roland Miller had already participated in the 8th Paris Biennial (in the audiovisual section), founded by André Malraux (1959) with the intention of hosting «non conventional practices». The Paris Biennial rejected since its origin, exhibitions and works of art, identifying itself and defending alternative practices. It’s possible that it had been in there that Egídio Álvaro met Shirley Cameron and Roland Miller and the invitation to go to Portugal initiated.

- ^ Egídio Álvaro collaborated with Diário Popular Newspaper.

- ^ Newspaper article not signed, «Dois artistas ingleses deram espectáculo na Avenida dos Aliados», in Diário Popular, 22-03-1974.

- ^ N.T – A Gallery in Lisbon. Nowadays it’s part of the Galerias Municipais de Lisboa – Lisbon’s Hall Art Galleries.

- ^ Jaime Ferreira, «Dois plastífices ingleses fazem escultura cénica», in Comércio do Porto, 1974 (newspaper clip without identification of date or page).

- ^ Roland Miller and Shirley Cameron, «Landscape and living spaces», Grantham, 28.01.1974, republished text in Revista de Artes Plásticas Nº5, September 1974.