Cinema as a Vehicle of Ideology

Sabrina Marques, Luís Mendonça, Carlos Natálio

CINEMA AS A VEHICLE OF IDEOLOGY

When beginning to think about images, the fundamental starting point is invariably the same: What is the value of each image and what makes that same value change through time?

Film-critic Bruno Andrade recently underlined the truth inscribed by Stéphane Delorme in his editorial for the 710th edition of Cahiers du Cinéma: «We assume that all great movies are experimental and an adventure inside the unexplored.»

And if experimentalism is the strength of re-invention in which cinema is built upon since its beginning, it must be remembered how this evolution did not happen without restrictions: it is cinema’s popular quality what makes it a particularly desirable vehicle for the diffusion of mass ideology, with a strategic potential recognized by all regimes. Lenine nationalizes cinema and photography in 1919 and the following decades will be ruled by the fundamental manifestos that delineate the first theories of montage. Consequently, the founding names will be the first to want to experiment outside the lines they themselves drew, caught in the rush of freedom where art reinvents itself beyond the ideological message. It will therefore be Eisenstein – among all the soviet authors, the one who better systematized the theory of montage, in structural masterpieces that go beyond its propaganda aspect (Battleship Potemkin, October, The Strike) – who also kept a secret drawer with a series of his own illustrations of explicit sexual content and who, after being successful, did not shy from trying his luck on the other side of the ideology, to Hollywood. Pabst, Lubitsch and Lang would head up there too, escaping the Nazi censorship. If Nadezhda Krupskaya, Lenin’s wife, was in charge of the Arts Committee, that included cinema’s supervision, also Vittorio Mussolini, the son of the Italian dictator, believed, as his father, in the power of the cinema, filling in a position as a critic in the journal Cinema, collaborating as a scriptwriter in a regime that trusted LUCE (Union for Cinematographic Education) with the function of producing propaganda.

In Portugal, censorship was one of the most central weapons in a vast repressive device: the Previous Exam (a legal euphemism for Censorship) not only intervened in the creation, circulation, distribution and sale of written publication, but also transpierced all the cultural and artistic production – theatre, cinema, television, radio, literature, fine arts. The censorial codes were in such a way dubious that in the 20th article of the Constitution, it could be read that «special laws will regulate the exercise of freedom of thought». António Ferro was the director of the National Secretary of Information, when in 1948 he promulgated Law 2027 that prohibited dubbing foreign films: «it is not allowed the distribution of foreign films dubbed in Portuguese language nor the importation of foreign films spoken in Portuguese language except for those directed in Brazil.» It is easy to understand how, in a pronouncedly illiterate country, it was more efficient to adulterate the message of the films by manipulating the translations or by leaving parts untranslated. (The practice in Franco’s Spain was even more extreme: films were dubbed and dialogues replaced for others more convenient to the censors). Manuel Mozos’ film, Cinema – Some cuts: Censorship, from 1999, shows 57 examples of cuts done by the Censorship Commission in between 1950 and 1972, exemplifying how films could only be exhibited after an amputation of the original works following a determined pre-agenda. It was maybe because of a quibble from having the same last name has the Spanish dictator, what allowed the outrageous erotic director Jess Franco to obtain multiple permissions to film in Portugal in the late New State, what would constitute one of the biggest flaws opened to the restrictions of cinematographic production in Portugal. And it is under the subject FLAW that we propose to unveil, in this collective dossier, the mastery of the secretly struck blows from various directors that, in several points of the globe, worked corseted by censorship codes.

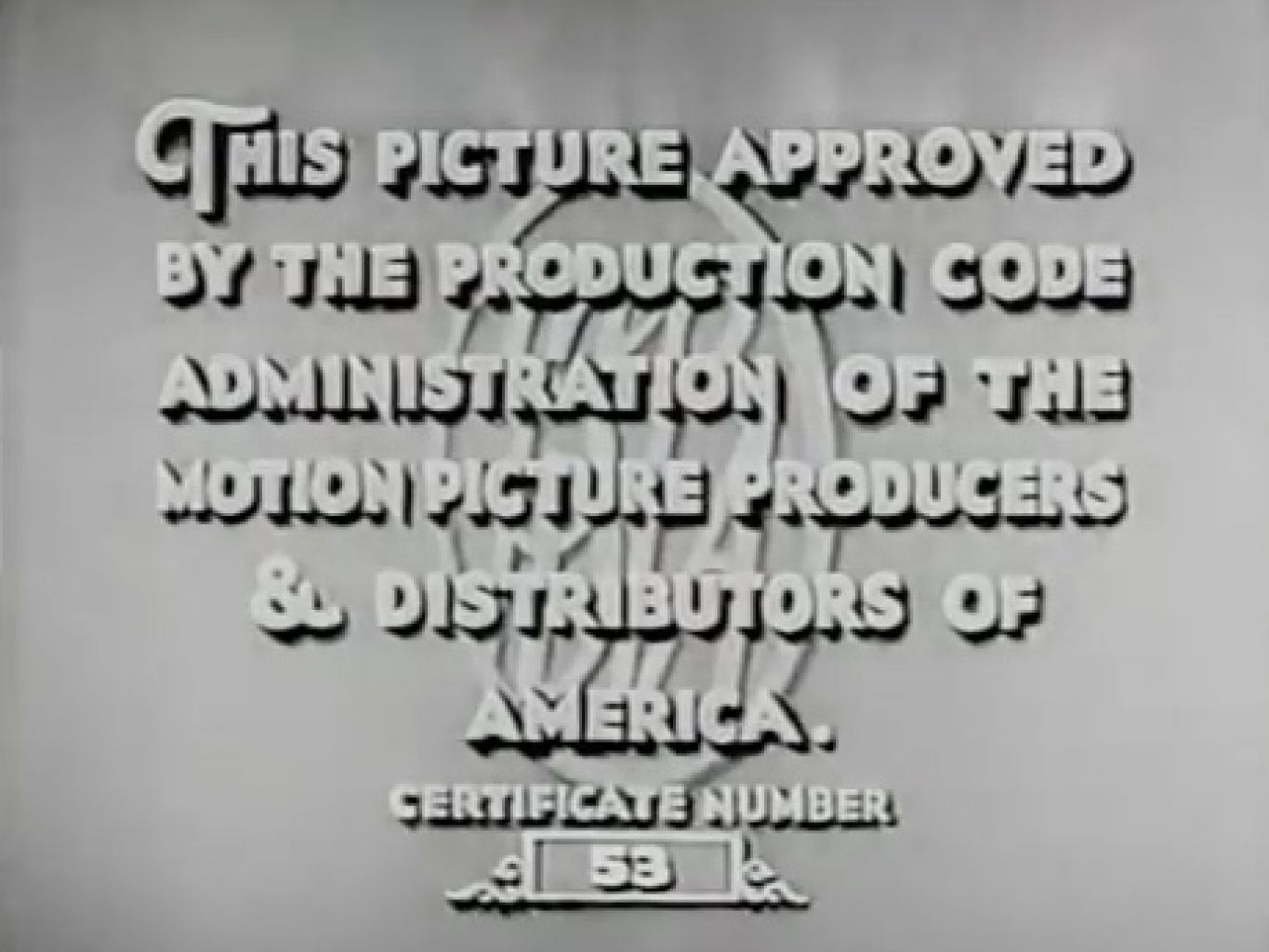

1. HAYS CODE

It is in 1922, in the early life of the talkies, that Hollywood comes up with the first intention to legislate a self-censorship code. It would be elaborated by the Presbyterian Will Hays and gradually put in action since 1930, having its decay in the 50s until 1966, when the Motion Picture Association of America introduced the ratings system. This «Movie Picture Production Code» consisted of a list of «Dont’s» and «Be Carefuls» that would remove the presence of nudity, illegal drug trade, white slavery, miscegenation or ridicularization of beliefs or nations, and that would recommend particular attention when showing the flag, fire guns, drugs, techniques of committing murder, brutality, prostitution, cruelty for children and animals, among dozens of other warnings. Hollywood seemed to conduct itself inside of a flux of ostensible freedom: in that same year of 1930 – in spite of the post-crash, a year of strong cinematographic production – films such as The Divorcee (Robert Z. Leonard), starring Norma Shearer or Anna Christie (Clarence Brown) with Greta Garbo are launched, two narratives led by emancipated women who smoke, drink and get divorces, separations and sexual adventures. In the decades of 1910 and 1920, these femme fatales, captivating characters in their complexity and challenging to the opposite sex, dominated the big screen. In these pre-code times, we saw a bisexual Greta Garbo cross-dressing in Queen Christina (Rouben Mamoulian, 1939), we saw Marlene Dietrich as an iconic Mata Hari (George Fitzmaurice, 1931), we saw luscious close-ups of Mae West in I’m No Angel (Wesley Ruggles, 1933) and we saw Barbara Stanwyck as a prostitute explored by the men in her own family in Baby Face (Alfred E. Green, 1933). All of a sudden, everything changed. If in the big screen, the stories told of schemes of survival and the social and moral precariousness of the post-depression American reality, the Christian conservatism was able to rapidly take over that powerful mass medium, with the intention of renewing society’s behavior through it.

1.2. KISSES, INVITATIONS TO TRANSGRESSION

One the most quoted escapes to the Code, exemplifying this need to circumvent the censorship by means of symbols is the famous scene of the kiss in Casablanca (Michael Curtiz, 1953). Facing the impossibility of showing the corporal encounter that will follow, from the intimacy of Humphrey Bogart and Ingrid Bergman we will go, through a fade-in, to a tower, a phallic symbol that leaves us in a subtle and ambiguous suggestion.

Also from 1953, From Here to Eternity (Fred Zinnemann, 1953) is a film eternized by that glorious kiss of Burt Lancaster and Debora Kerr, half-naked by the sea. The survival of this suggestive scene considering the censorial restrictions is one of the clearest statements of Hollywood’s will to get rid of the Hays Code. It was the arrival to the American theatres in the 60s, of European films that were getting increasingly popular, what pressured Hollywood to ease the restrictions in cinematographic production. However, pudency has never abandoned the entrails of the American cinema and nudity still occurs within extreme contention today. Who has never heard from an American, in any comical reductio ad absurdum, that European films are about nudity at any excuse?

(Sabrina Marques)

1.3. THE LEGS OF OTTO PREMINGER AND ALLAN DWAN

The Hays Code repressed explicit violence and sex. The great fetishists of the seventh art applauded the limitations. They saw in the impossibility of showing the power to imply. There is a secretly pervert tone beneath the commandments that the Hays Code sculpted for decades in the super-ego of the industry. With the interdiction, and we didn’t need Bataille to know that, we discover the power of eroticism in the big screen. As if in each interdiction we tried to explore other territories of sexuality. In a movie «under censorship», a shoe, a stocking, part of a leg, some bare feet if at the beginning are metonymic of the male desire for the female body, when the ability of filming them perfects itself the male desire no longer wants more the whole than the part. There was a filmmaker that made a whole career celebrating the censorship’s limitations: Otto Preminger. I don't want to talk about the «panties» used as evidence in the trial that takes place in Anatomy of a Murder (1959), and that infuriated the censors, or about the fearless way that before that he dealt with the subject of drug addiction in Man With the Golden Arm (1955). I want to speak about a director that knew as few did how to put on film their muse’s legs. Let’s watch or re-watch the introductory scene of Linda Darnell in Fallen Angel (1945). She enters the diner, Preminger is awaiting her with a wide shot, so that the spectator can properly admire the sight of her long legs. Without cutting, the camera follows her languorous motion, from the entering door until the first chair that seems also to be waiting for her arrival. Darnell sits, takes of her shoe and rubs her exhausted foot. It’s a ritual of seduction. We know that our hero, Dana Andrews, is watching the whole scene – also in continuum, without a cut, without blinking. We know by then that he will not let her go. There are no angels in here.

Another fetishistic director that struggled with censorship: Dwan, one of the few directors in film history that we can call «total», since he began his career in the silent era and said farewell to cinema with the fall of classical Hollywood – and its censorship code. In the fifties he directs under RKO a number of melodramas and westerns with the help of producer Benedict Bogeaus. At least in two of them it’s possible to witness the attraction that this director had to the vertical eroticism of the leg. In Pearl of the South Pacific (1955) he gets an ideal set as a pretext to show to the world, in a variety of angles, the maddening legs of Virginia Mayo. The tropical climate in a far region of the Pacific Sea, far away from civilization, gave the permanent state of nakedness of Mayo’s legs an impression of verisimilitude to the censors’ eyes. Afterwards, came an even more exciting scandal: Slightly Scarlet (1956). The title says all. The movie is red not by shame but by seemingly lacking it. On one side, the men with power, swindlers, blackmailers, corrupt. On the other side, two sisters, one thirsty with power and the other one trapped in her compulsions: sex and money. The first one is played by Rhonda Fleming and looks like a lady compared to her kleptomaniac and nymphomaniac sister played by Arlene Dahl. Her obsessions serve Dwan’s obsession for legs. This noir at the verge of implosion, implosion of color, heat and anger, is a shameless celebration of the power that those legs can have in a body openly and explicitly neurotic. I can imagine the state of tension of the male audience while watching this movie: where is she (Dahl) going and until when does he (Dwan) will follow her?! Two scenes are particularly enlightening about this whole process of fetishistic empowerment. The corrupt politician comes back to his beach house, expecting to find it empty. However, as soon as he enters the house, he sees what he didn’t expect: in the couch there is Arlene Dahl. Her presence is flagged by her legs that move in the air. Dwan talked about how he tried to overcome his desire of showing Dahl completely naked in that couch. In another moment, she voluptuously moves with her feet a pile of money that the criminal threw to the carpet. The eroticism of power and money couldn’t get a more eloquent representation. Dwan is always finding in the exhibitionist play of female legs the sweet and inevitable starting point to the corruption of the soul. Hays didn’t have a chance.

(Luís Mendonça)

1.4. IT HAPPENED ONE NIGHT (FRANK CAPRA)

In Portuguese there is this saying that goes something like this: «it is by laughing that the truth is revealed». And there is a rougher version: «The monkey was only playing but he ended up impregnating his mother». Common to both sayings is this notion by which we value the adjective «dramatic» in the expression «dramatic comedy». In other words, the capacity of comedy to produce content for serious reflection, besides the anesthetizing filter of laughter. It came then naturally that it was comedy, and in particular the screwball comedy, the one that better perfected sophisticated systems of gaps or skillful circumventions of the decency codes. Namely, the one that was put in place between 1930 and 1966 in American cinema – the Hays Code. We can say that part of the importance of filmmakers like Ernst Lubitsch or Billy Wilder was the perfecting of such a filter system, more or less invisible, dominating the technique of sexual innuendo or double entendre.

However, it dates early from 1934, when Hays Code was at its highest, one of the films that summarized in a very completed way the art of saying and showing everything that is needed without really doing it. I’m talking of course of It Happened One Night by Frank Capra of whom is possible, if we want to, to talk solely in an «ordinary» fashion, saying everything which was supposed to be concealed but whose elaborated slits suggest. First, we are dealing with a story of a «forbidden statute»: a rich woman (Claudette Colbert) who, despite having everything, can only get satisfaction from an ordinary man (Clark Gable) whom she meets at a bus and with whom she will «sleep» repeatedly while being married to someone else. Then we have the title that draws attention for what is going to take place at night: the first nights, we have the foreplay with Gable’s striptease (his naked torso being one of the film’s female audience attractions) and his words «maybe you’re curious about how a man undresses» (and it is because of these that he will lose along the way that he will want to be repaid by Colbert’s millionaire father); in the last one, the expected desert, sex.

The trip of these two to New York whose goal is the fulfillment of desire, Capra stages it as a progressive approximation and will borrow the least expected book and the final metaphor for physical love: the Bible and the walls of Jericho. In the first night the two spend in the same hotel room, Gable hangs a blanket in between the two beds. This blanket is the wall of Jericho, separating each one’s space. In the second night the wall stays put but there is already an important transformation. First, she wins the first battle and we witness the failure of Gable’s thumbs («keep your eye on that thumb and see what happens») and the success of Colbert’s legs in hitchhiking. He gets annoyed and it is not difficult to see a harsh allusion to prostitution in his reply: «Why won’t you take off all your clothes and stop 40 cars?»

But from this ride she is able to get, the ritual of fascination of the female by the male is consummated: he runs searching for his stolen bag and comes from the «battleground» with a black eye and a car of his «own» that rapidly will be without gas (new allusion to the «failing thumb»). But when he arrives, she already wants to eat Gable’s carrots. Just afterwards, in that second night in a hotel, she already crosses the wall to the other side, refusing to go to her aviator’s arms and wanting to run away with him. But is it not time yet. It is almost the moment but he still doesn’t have the trumpet, with which he appeased Colbert in the first night. When the film ends with that genius shot of the wall /blanket being tore down (the slit on the wall as penetration) and the notes of the trumpet, we understand that Capra only wants to film sex, or, the «phallic sound» penetrating the wall. And this act converted into objects and sounds of the world is of more interest to the filmmaker than to show the reunion of the discordant couple. And it was on that night that all happened, on that night in which we didn’t see anything but saw everything. This everything was the objects, what was hidden, the desire as a progression in space (after all It Happened One Night is a traveling film) and a continuous disclosure. Be it with Hays Code or any other forbidden we always need a «wall» for the emergence of a slit, for the seeing/acting «across of» penetration.

(Carlos Natálio)