The workshop as an ephemeral community

Evanthia TsantilaLast February the international arts community bade farewell to the great artist Jannis Kounellis.

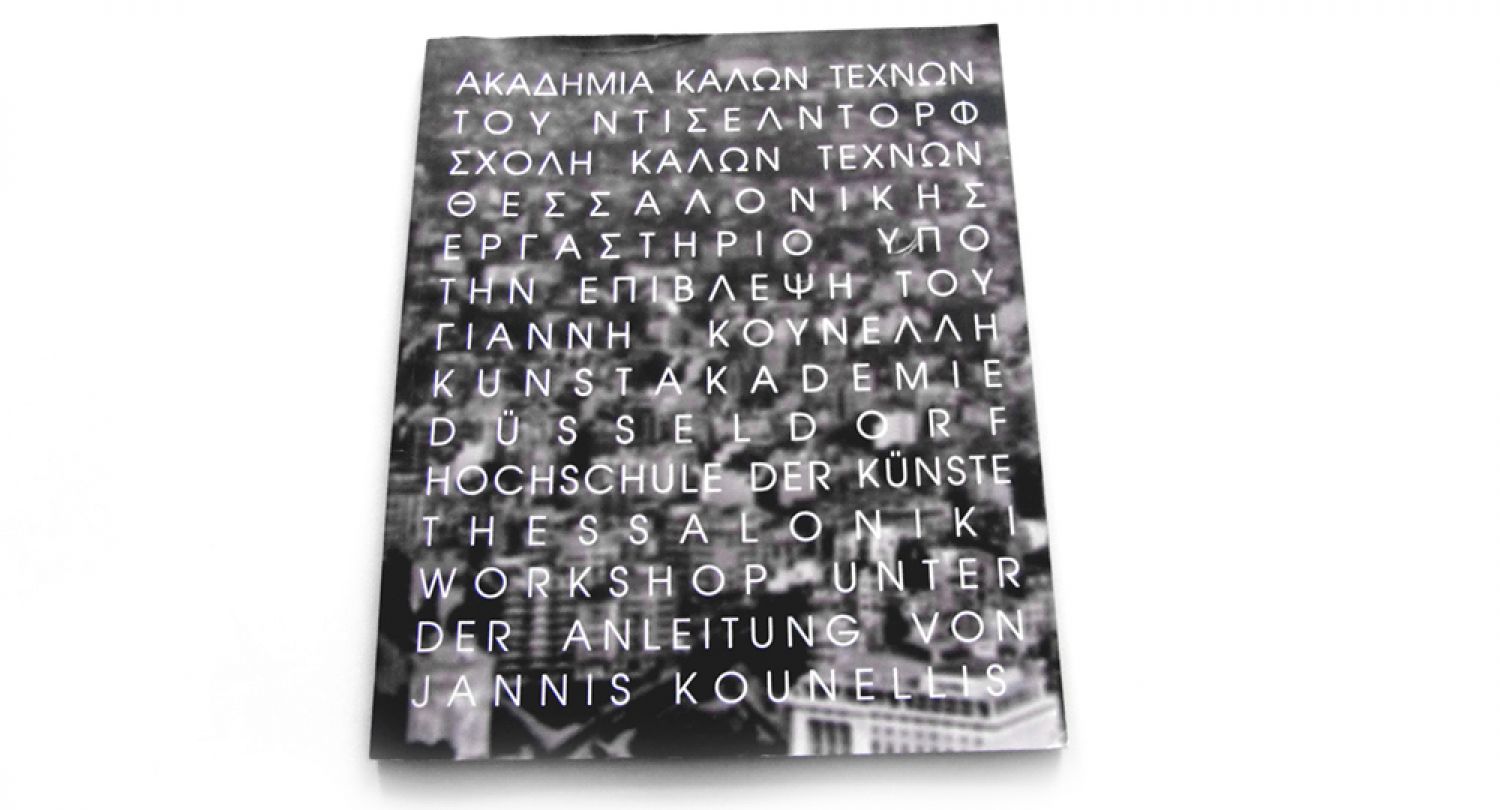

It was twenty years ago today that our class from the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, where Kounellis taught from 1993 to 2001, travelled to Thessaloniki with him for an art workshop. This initiative was my first attempt, alongside my work as an artist, at creating a platform for artistic collaboration and research. Looking back now, it seems the claim our project made still holds: how to create the conditions for artistic freedom within the collective efforts of an ephemeral community.

I began my studies at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf in the year 1991, after moving to Germany from my birthplace in Thessaloniki, Greece. Having invariably called into question the prevalent realities of Thessaloniki’s art world, I felt the need to leave. I believed that I could gain a better understanding of myself and my place in the world, if I moved to another place. I wanted to further and enhance my artistic explorations, place my work within a wider critical context and sharpen and elaborate my artistic arguments and claims.

Constantly moving between the familiar and the unfamiliar other place resulted in a continuous interchange between the ‘I’ and the ‘Other’, until that ‘Other’, the stranger was myself. The ‘Other’ with whom I came into contact in the new place was a multitude of five hundred others. This ‘Other’ was not, and could never have been, some undivided entity or uniform community. This ‘Other’ was all five hundred of us who filled the halls of the Kunstakademie working, creating in a spirit of agreement and disagreement, of compromise and contention. Although some artists among us took on the role of advocate for a country, ethnicity, tradition, or religion, nevertheless, we were all staked on and actively engaged in a practice whose grounds, principles and problems we shared.

In 1995 I submitted a proposal to the Art Committee of the organisation Thessaloniki Capital of Culture '97 for putting together and running a workshop for young artists, graduates from the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf and the Thessaloniki School of Fine Arts. I also proposed Jannis Kounellis, my teacher at the time, as the workshop’s supervisor. The core idea of the project was that all of us who came from different cultures, traditions and practices would meet within a designated space and time to produce a series of works that would be shown in a group exhibition. The proposal was accepted and on finalising the agreement I began deliberating on and drafting the terms of this encounter.

Jannis Kounellis suggested that I put together a list of participants from the Kunstakademie. My basic selection criteria were the artists’ quality of work; their insights into the difficulties and challenges facing art as such; their work with diverse artistic media and their employment of different artistic strategies. The Thessaloniki School of Fine Arts participants were selected by their teachers.

The final group consisted of 32 students who not only were from two different schools but also from a number of different countries (Austria, Cyprus, Germany, Greece, Italy, Serbia, South Korea and Switzerland).

The Kunstakademie Düsseldorf is a well renowned school in the heart of one of the largest metropolitan areas in Germany. The Thessaloniki School of Fine Arts is situated in a city with a long and notable history and it may yet come to play an important role in the art world’s ‘periphery’. The two schools differ in terms of academic culture, policy and artistic direction. The concept of ‘academy’ within the German educational system refers more to free artistic exploration and research than designates a space of study according to the norms of a given discipline. The Kunstakademie graduates, several of whom had completed their core art education in other countries, had experience of workshops and exhibitions and were familiar with the challenges and difficulties a project of this kind poses for its participants.

In planning the workshop, my main objective was, given the considerable differences of approach to art practices and debates, to create the conditions upon which participation of both sides could take place on a more equal footing. With that in mind, I started working with all the participants on the project, particularly the Greek side, a year in advance of the workshop’s opening day. The first step was to present the work of each participant to all the others so as to familiarise themselves, as much as possible, with the respective similarities and differences of their work. Moreover, I tried to promote and encourage the exchange of ideas and foster a spirit of collaboration and collective work. Given that the ultimate reason and purpose of a workshop is educational, the basic prerequisite and point of consensus was that this project served as the means to exploring openly and interactively artistic praxis.

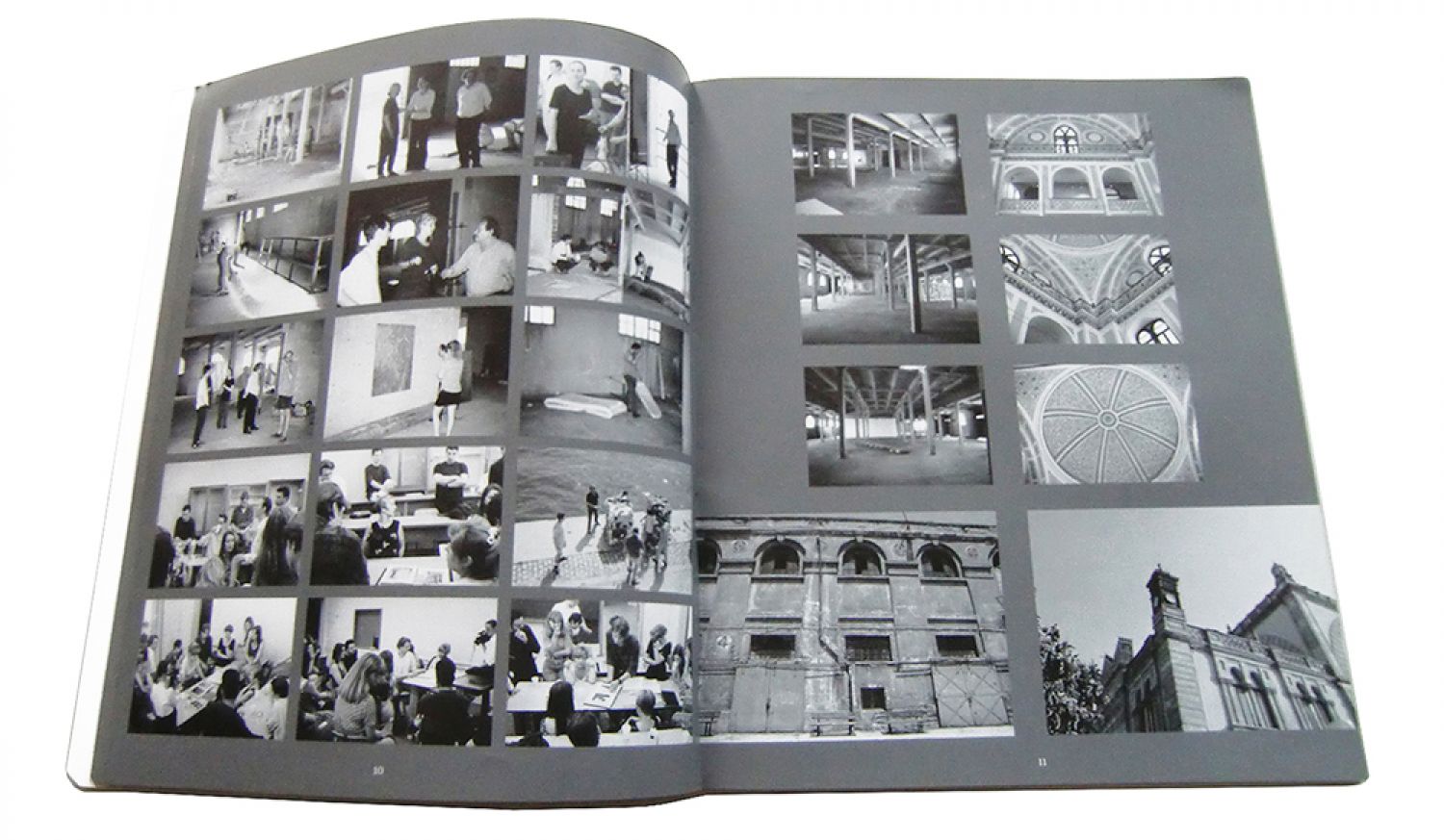

The workshop took place in Thessaloniki in May 1997 and lasted a whole month. The Goethe Institute and the German Consulate gave us the use of the old German School premises. It was there that the graduates of both schools met for the first time, and work started immediately. The new place as much as the demands of shared space put pressure on all settled sense of self. Familiar roles that one expected to be fulfilled were turned on their heads. The participants suddenly found themselves outside their safety zone. The certainty of their views and ideas was challenged, once they realised that their presuppositions could no longer hold, could not fall into place. The familiar and the unfamiliar, proximity and distance kept alternating and undergoing reversals. Feelings of discomposure and composure were shared all around.

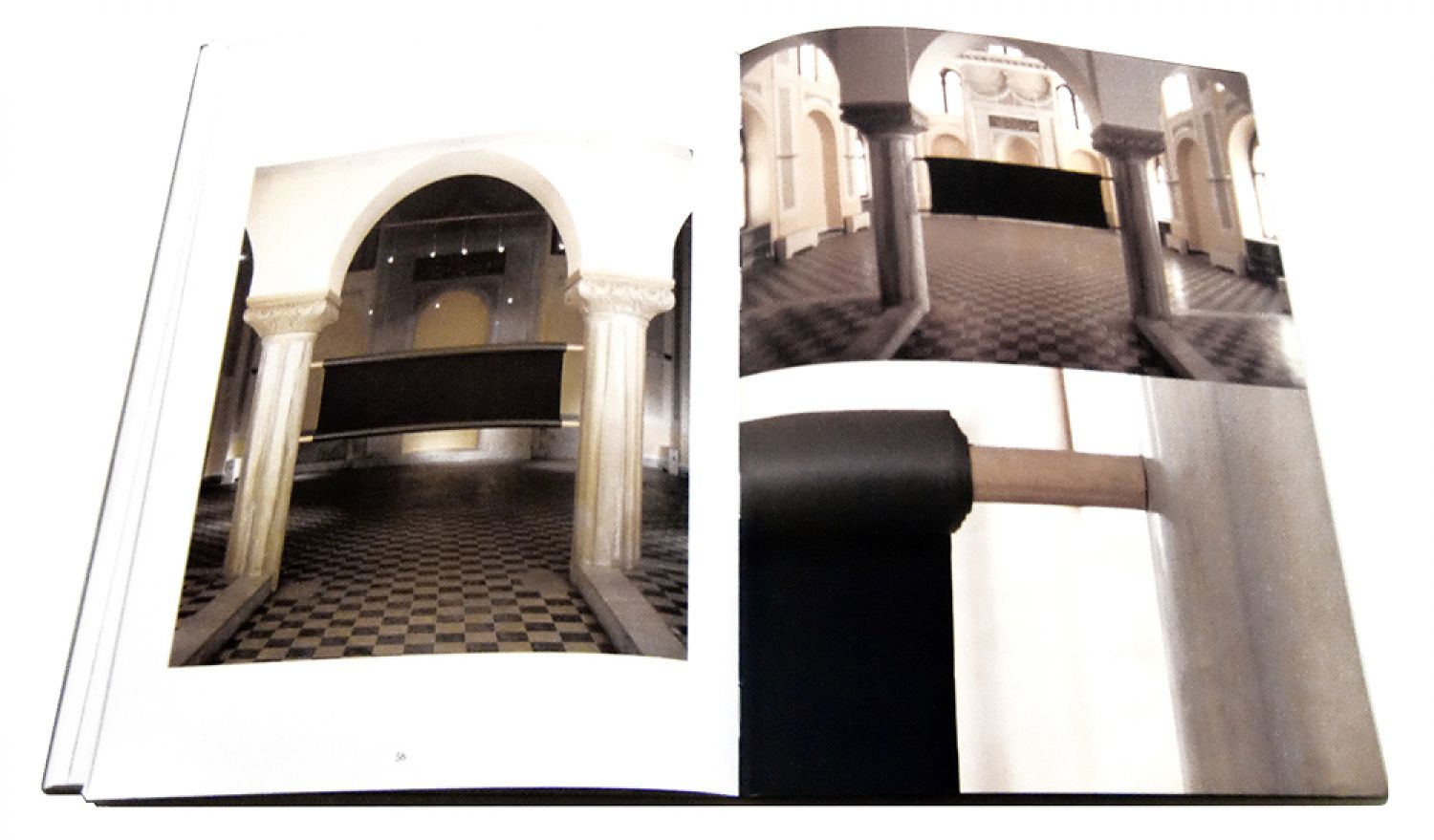

What followed forced all previously decided plans of work to be altered and rethought. From the very first meeting it became apparent that the workshop was confronted with a serious practical, and by extend artistic, problem regarding the exhibition space. Initially, the organisation Thessaloniki Capital of Culture '97 gave us the Old Archaeological Museum (previously Yeni Tzami, the mosque of the Islamicised Jews of Thessaloniki), a small grade listed building laden with symbols. The idiosyncrasies of the building’s design and the spatial limitations it imposed on the participants played a decisive role in deciding the shape and form of shared space, of the coexistence of 32 different works. Understanding that the challenges posed by the demands of shared space required collective input from all participants, I decided to put the issue in question before the entire group for deliberation rather than simply find an alternative space. During our first meeting, I called for imaginative ways of working through such challenges. The day after, one of the Kunstakademie graduates proposed that a collective work be produced and exhibited. Such approach would have partially addressed our trying spatial problems and, at the same time, served well the workshop’s objective aim, that of collaboration; however, it could have equally served as a smokescreen, masking nebulous insecurities or silencing productive artistic conflicts, ultimately neutralising outbursts of brilliance. The concept of a collective work was, admittedly, formally bold and radical as well as politically controversial (given the symbolism of the particular building). It initiated an interesting and lively debate that lead to intense and meaningful disputes not only between the different schools but also between individual members of the same school. Not only did graduates of the Kunstakademie for the first time entertain the thought of collectively producing a work but a number of them also subscribed to the proposal. In marked contrast, their Greek counterparts unanimously and categorically refused to participate in this venture; some because they could not understand what was proposed and others because they disagreed with what was proposed.

At that crucial turning point, Jannis Kounellis arrived on the scene. His always inspiring presence could not have been more timely and his contribution acted as a catalyst for moving forward. On the other hand, his arrival on the second half of the workshop created a strange atmosphere. Kounellis’ own students who felt familiar with their teacher, and who may have been lead on account of this to believe they had a more direct access to him, realised that the language the Greek graduates shared with him created an immediacy they did not have. Jannis Kounellis taught them via an interpreter who translated from Italian (Kounellis was naturalised Italian) to English and German.

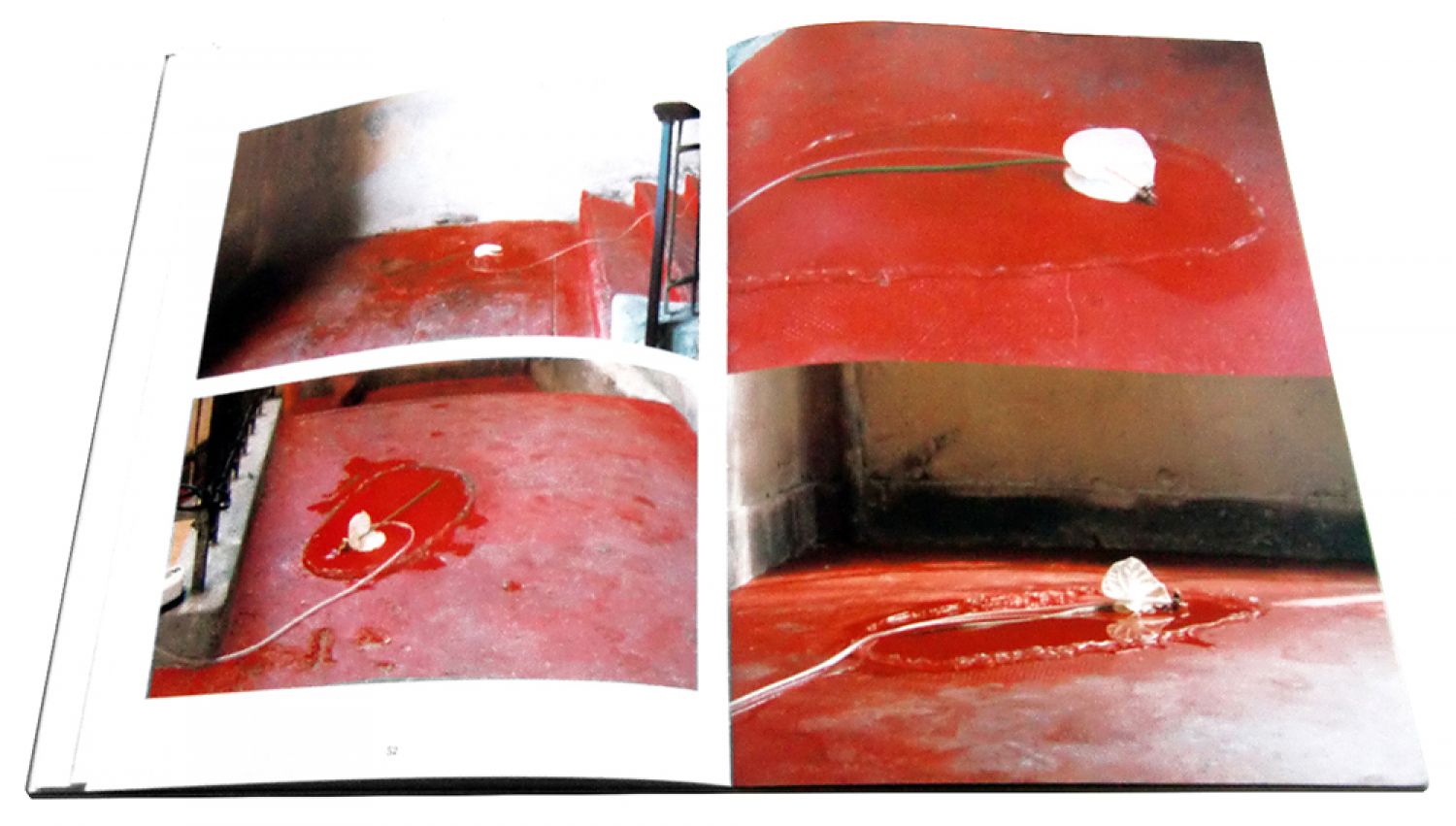

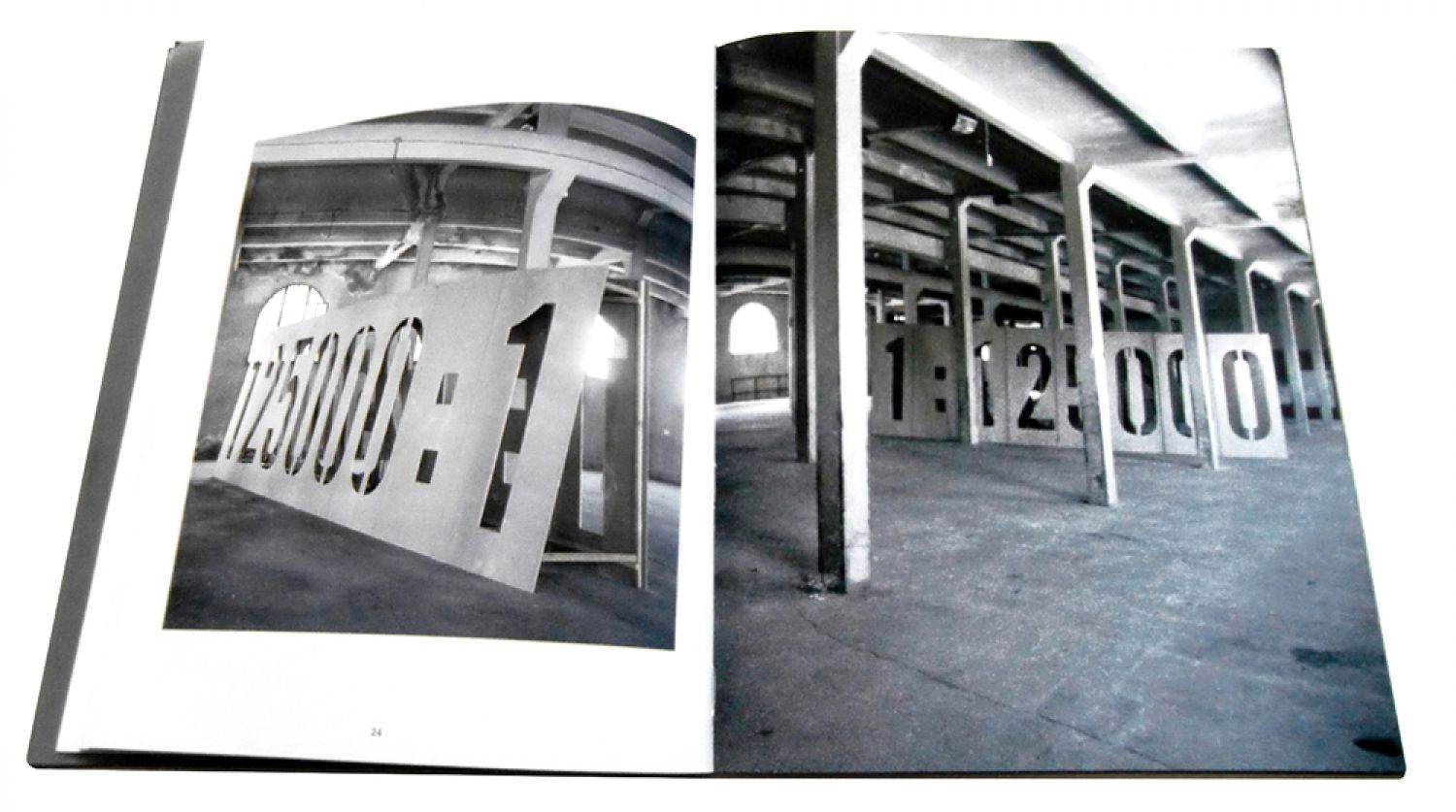

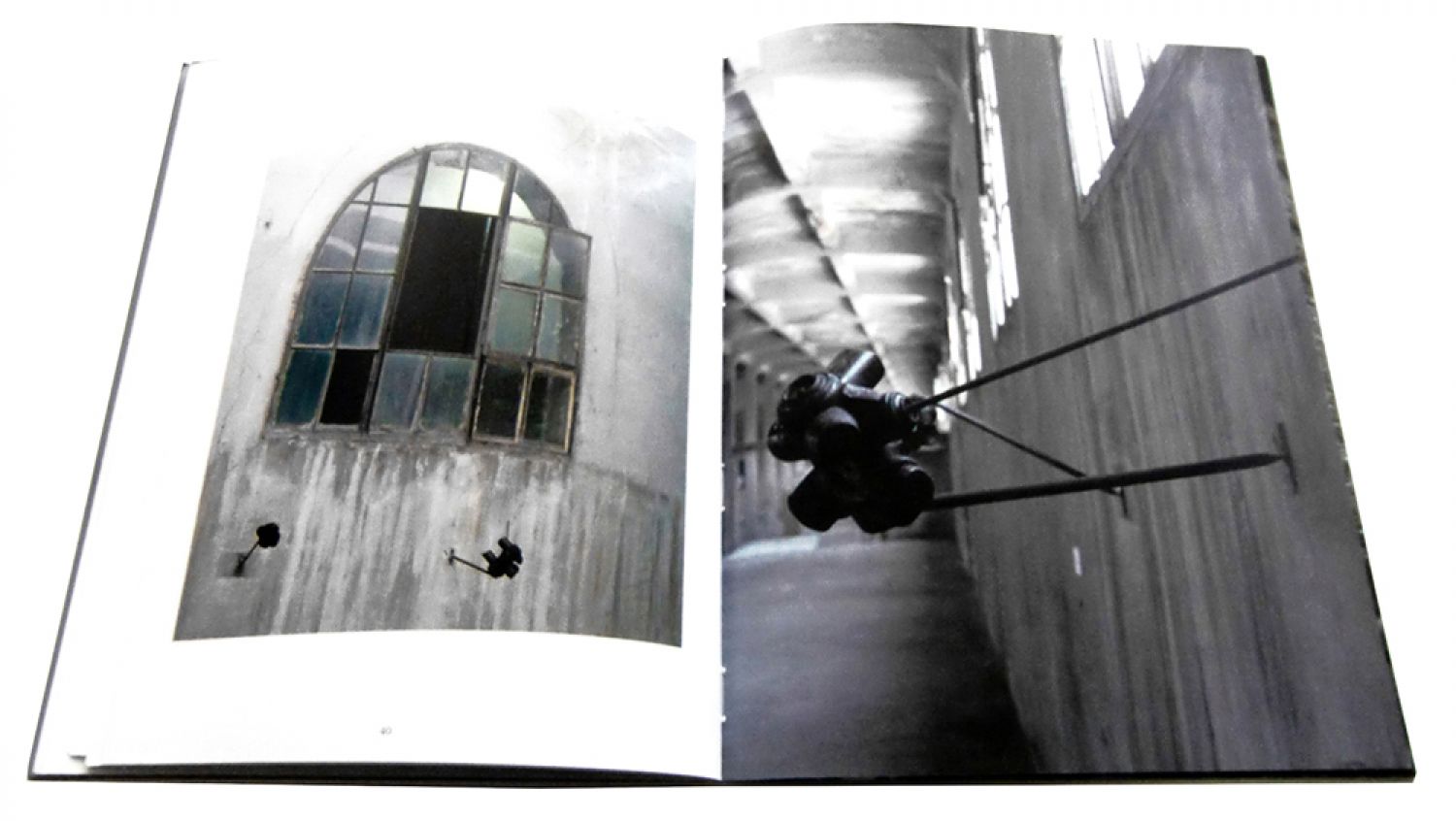

In the end, the practical solution of finding an additional exhibition space became pressing. The organisation Thessaloniki Capital of Culture '97 gave us an abandoned warehouse in the Customs section of the city’s Port Authority that could easily house all 32 works. I nevertheless decided to keep the initial space in the Yeni Tzami as well, first because many a fruitful debate took place around its specific challenges and second because some of the participants were already in an advanced stage of conceiving and planning their work with that space in mind. Thus, the 32 participants were divided between the two places, and after peaceful agreement among them exhibition spaces were allocated and work proceeded to completion. Both exhibitions opened on the same day. The artists donated the works to the city of Thessaloniki and after the end of the exhibition they were stored in the warehouses of the organisation Thessaloniki Capital of Culture '97. They later became part of the permanent collection of the Thessaloniki State Museum of Contemporary Art.

The deliberate absence of a priori strictly defined terms accompanied by a strong obligation to collaborate lead the participants out of the field of mere exchange of ideas to a more essential and fundamental dialogue through the exploratory paths that constitute the art work as such and through the artists' displacement to a new cultural context, new for all participants alike. All proximity and distance between the two schools, the variety of artistic media employed, the difference of artistic expressions as well as the difference and variety of ideas and problems served to illuminate the matter of a work’s exhibition in its search for a place. Far more than the ordering of works in space the exhibition turned into the constitution of a unity in which, on the one hand, the autonomy of the art work was preserved and, on the other, the unique quality of the work’s relation to its new place was assured.

At times, the need for creating, developing and supporting an interstitial space, a space-in-between arises. A space where economic and political antagonisms and entrenched, organised interests can be suspended; a space that takes the form of an ‘otherwhere’, an ‘other place’, where artistic productions can escape their immediate subsumption under the edicts and calculated trends of the culture industry; a place where artistic productions are not eventually reduced to passing displays of dramatic flair. It is this ‘other’, this suspended place within the space of antagonisms that artists seek to craft, to invent in order to be able to attend to the demands and requirements of their art work. Not only the demands of a work’s presentation and circulation in the world at large but also, crucially, the demands that the conditions of creating works of art be displaced and recast in a way that would better serve the constitution of the art work by its own elements. The whole process feels like a journey through an indistinct, obscure passage where the only thing certain is that the destination is unknown. Moreover, the desire to reach it may not be fulfilled. Nevertheless, we artists start with this desire and aim to reach this invented ‘otherwhere’, this place where the art work assumes another position than the one already determined for it. The times where this need is felt constitute a necessary and sufficient place within which our work can come into being. It is there in that invented ‘other place’ that we also desire our work to meet with the Other, the imagined, invented Other who emerges in this suspension within the tangle of mass equivocations. This Other takes on the quality of an ideal viewer and an ideal interpreter of the art work. The encounter between work and its interpretive reception in the suspended terrain of the invented Otherwhere and the invented Other has only one purpose, to face the Here and Now, to face experience.

Initiatives like the Thessaloniki Workshop serve as manifestations of a praxis that runs parallel with institutions and their established strategies and they may even be supported by the later while maintaining their independence. They might work in concord with institutional practices but they might equally oppose and confront them. In this context, participants are called upon to think through questions concerning not only practical matters in the artistic process but also the possibilities of artistic practices as such. How can one still be invested in revitalising the gaze, in creating spaces of shared experience? How can one imagine and configure another experience, one beyond the structures of the here and now, in order to create in the here and now in this experience?

The work of art is neither some sealed fate, nor something self-evident and predetermined (by the laws or trends of taste, prevalent norms of artistic practice, institutional directives, strategies or policies), it does not announce itself in advance nor is it the result of an applied method. Nothing guarantees its everlasting production and transmission. Would it end up as a mere exhibit in a future anthropological museum, a sample of a civilisation that raised questions of truth and freedom by means of a peculiar practice and its mutable and protean creations which it used to call art?

–

Translated from the Greek by Harry Marandi

Participants:

Thomas Breuer, Claus Brunsmann, Seung-Un Chung, Brigitte Dams, Michael Denzel, Felix Ersig, Harald Hofmann, Tatiana Ilic, Markus Karstiess, Patrizia Kristaldi, Christiane Löhr, Maria Rigoutsou, Ulrike Rutschmann, Bernd Ruzicska, Felix Schramm, Bärbel Schülte-Kellinghaus, Sandra Vöts, Annett Weissenburger (Kunstakademie Düsseldorf)

Haris Anastasiadis, Nikos Arvanitis, Thanasis Argianas, Eleni Valavani, Vasilis Kalantzis, Panagiota Kapela, Nektaria Kotamanidou, Christina Mitrentze, Dimitris Neokleous, Stella Papadopoulou, Christos Ponis, Efi Souravla, Georgia Touliatou, Konstantinos Tsopelas (Thessaloniki School of Fine Arts)

Supervisor: Jannis Kounellis

Concept, organisation and curatorial work: Evanthia Tsantila

Architectural adaptation and artwork production: Alexios Dallas

Exhibition photographer: Athanassios Karanikolas

In January 2000, a catalogue was published with the support of J. F. Costopoulos Foundation.