THE PENCIL OF NATURE

Anna Artaker

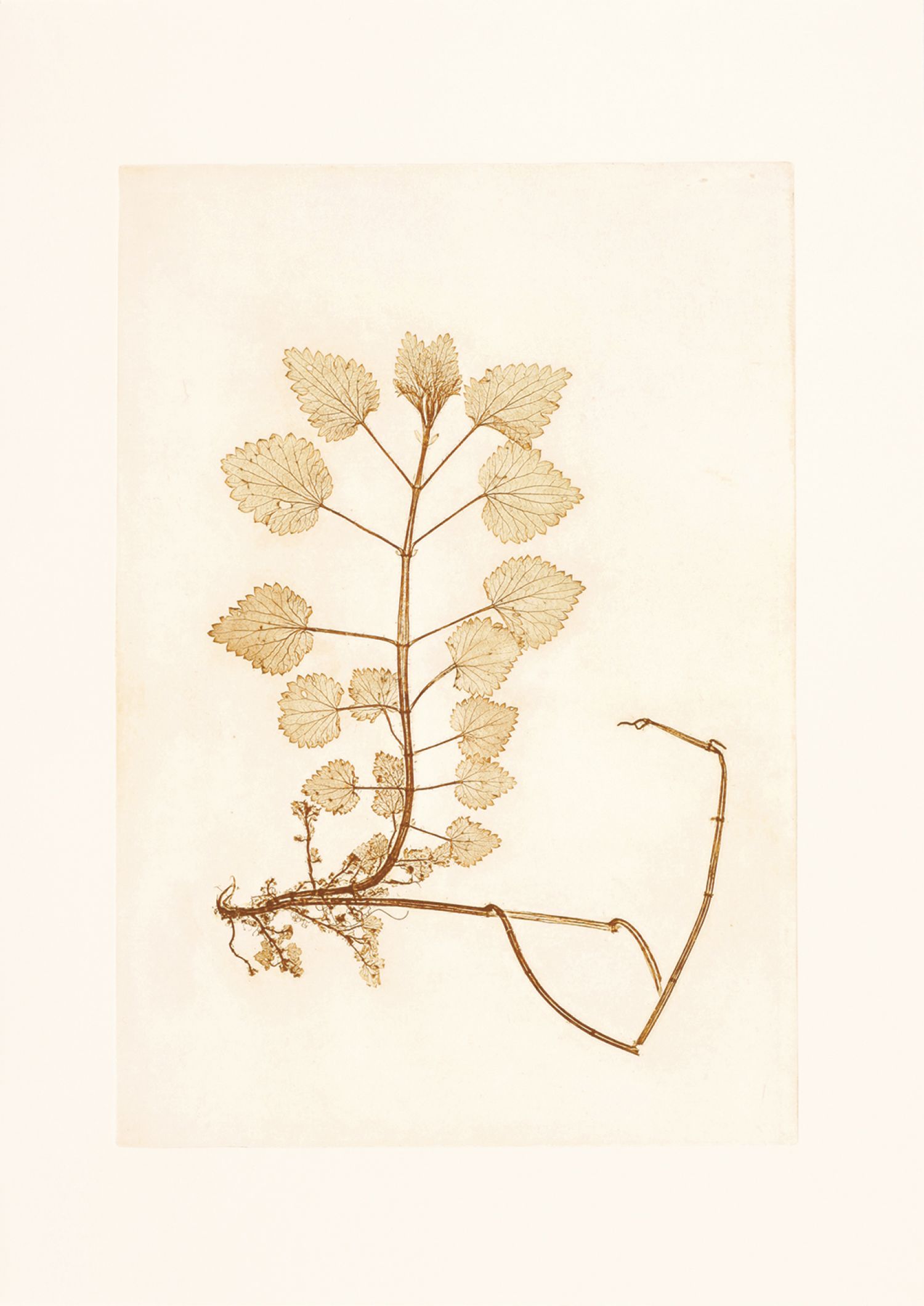

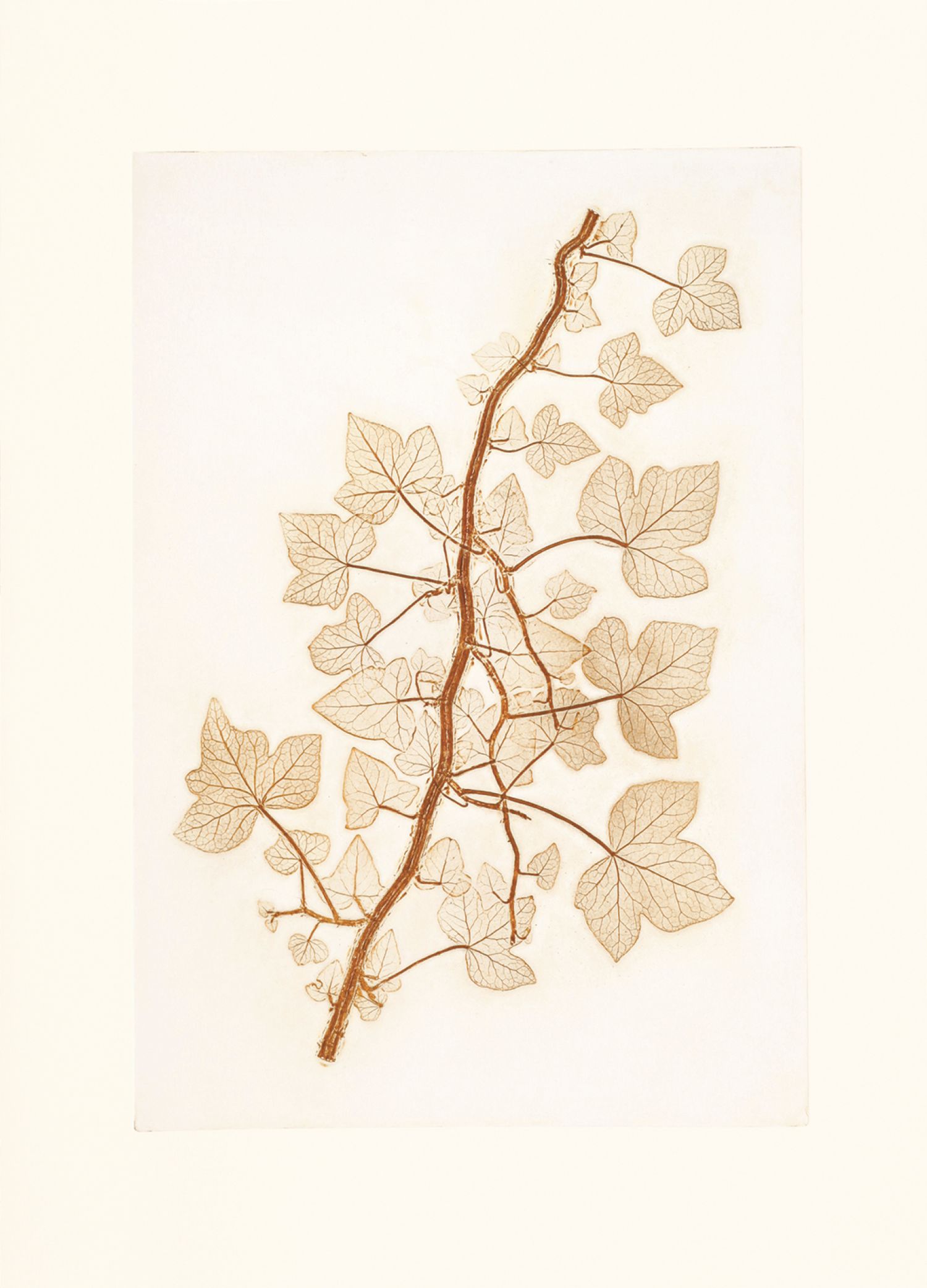

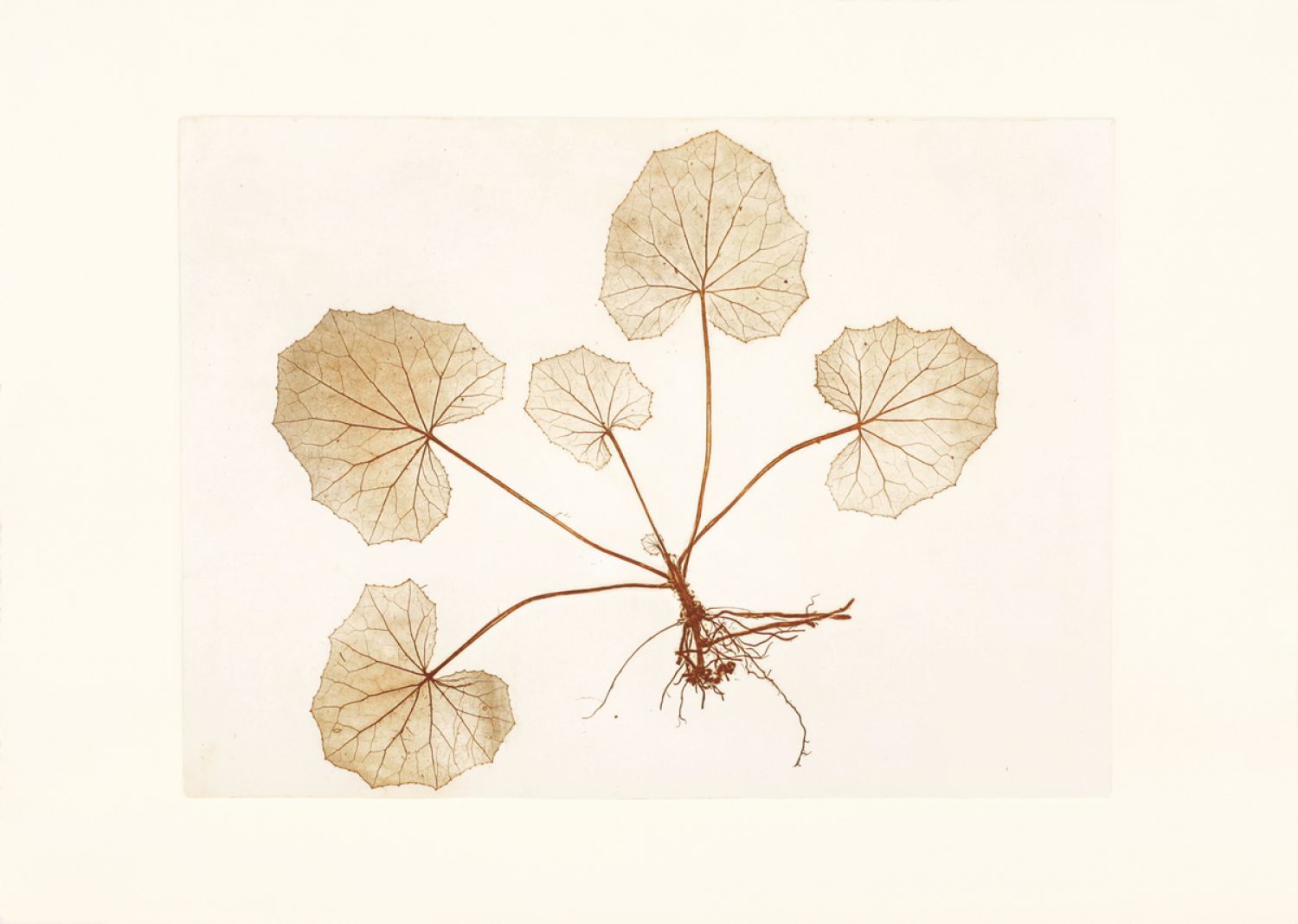

THE PENCIL OF NATURE, on-going series of nature prints «after Talbot», 2017.

Botanical nature prints on handmade rag paper, 60 x 43,5 cm each (unframed)

–

For my on-going series of nature prints I have borrowed the title of the publication with which William Henry Fox Talbot introduced his photographic process in 1844: The Pencil of Nature. However, rather than specifically responding to the content of the book, I use the title as code for the beginnings of photography. Starting point for my series of nature prints are not the twenty-four photographs included in The Pencil of Nature, but the numerous botanical photograms Talbot had been producing since the mid 1830ies in his photographic experiments. To test his photographic process he used plants that he pressed onto the sensitised paper with glass plates, which he then exposed to sunlight. The parts exposed to the light turned dark while the ones covered by the plant remained the colour of paper. By then stopping this photochemical reaction Talbot could fixate the image of a plant as a negative silhouette, producing what today we call a photogram.

My series THE PENCIL OF NATURE associates this «birth of photography from the spirit of botany» with nature printing, a technique perfected in Vienna in the 1840s, exactly the time of Talbot’s publication. Talbot’s botanical photograms – which are hardly ever exhibited for conservatory reasons and until today have only been published haphazardly – not only resemble nature prints visually, but also in regard to the production process: in both cases actual physical contact with the depicted plant generates the image. Nature printing developed in Europe parallel to the botanical tradition of creating herbariums. Since the durability of a herbarium is limited botanists started to ink the dried and pressed plants and to print them on paper. Usually both sides of the plant were inked. It was then placed between two sheets of paper and rubbed with a bone folder or just the heel of the hand to achieve a true-to-the-original imprint. This process could be repeated two more times without additional ink: this way up to six prints could be obtained, before the plant would be too used for printing. The process developed in the Austrian National Printing Office (k. k. Hof- und Staatsdruckerei) under the direction of Alois Auer is more complex. Starting from an imprint of the motif to be printed in a sheet of lead, a copper intaglio plate is made using galvanoplasty or electroplating: From the lead imprint, which is a negative relief of the plant, a mould is made in the electroplating bath which serves as a matrix for a second mould. This second mould corresponds to the imprint in lead, but is made of copper, a material solid and flexible enough to be used as a printing plate for intaglio printing. If worn out by printing additional plates can be produced from the matrix, meaning the technique in principle enables an unlimited print run. The prints achieved this way are not only true-to-original images of, but also through nature, just like Talbot claimed for photography.

THE PENCIL OF NATURE emphasises this kinship between early photography and nature printing not only by adopting Talbot’s title, but also through the choice of motifs: for the series of nature prints I used the same species of plants like Talbot for his photographic experiments almost two centuries earlier. Being an avid amateur botanist, we can assume that Talbot was aware of the technique of nature printing.

Yet there might be another link between the origins of photography and the realm of plants, that can also justify the publication of the series of nature prints in the Solar-issue of wrongwrong.net: Long before Talbot’s or other pioneers like Anna Atkin’s photographic experiments with plants people had observed, that organic substances react chemically to light, like colours fading when exposed to the sun. The same is true for plants. We know that plants that are shut off from light cannot develop chlorophyll-green and remain strangely pale. So there might be indeed a parallel history of the observation of photosynthesis in plants and the history of photography, like THE PENCIL OF NATURE proposes.

–

For more information on the framework of the project: https://criticalhabitations.wordpress.com/debate/pluralising-practices/anna-artaker-mediums-of-history/

or

Lisa Ortner-Kreil, Ingried Brugger (eds.), Anna Artaker. THE PENCIL OF NATURE, ex.-cat. Bank Austria Kunstforum Wien, Verlag für moderne Kunst Wien, 2017