Ruins of the contemporary world

Sebnem SoherIn visual arts and architecture media, the transformed, appropriated examples of the modernist buildings and even neighbourhoods have a special importance. They are mostly very powerful images loaded with tons of information, but also accompanied by an uncanny feeling. In those images, we are looking at man-made landscapes – professionally designed and sometimes not very much so. Sometimes they are Sometimes they are created that way because of the urgent needs or available material or knowledge. We might or might not see people, but we see a lot about people. We are regarding the lives, the homes of others. And just like Susan Sontag once wrote[1], there is a problematic side to images, since they are simplifying and creating an illusion of a silent agreement, a common view, a rhetoric[2]. Yet, these ruined modernisms with all their new meanings contain lives, problems, potential situations, lessons, needs to be worked on and to be worked with, rather than only provoking aesthetic inspirations or a consensus about the problems of urbanization and what was considered «ugly». This text will be about this constant shift of what is appreciated in architecture.

***

A United Nations report refers that sometime around 2009, the number of urban populations surpassed the number of the rural and the world became a more urban place in numbers[3]. While in 1990, there were only 10 mega-cities, housing 153 million people; in 2014 the number of mega-cities reached 28 and their population rose to 453 million people[4]. The same report is mentioning the fast growth of further small cities. Urban politics are oriented to attract private investment[5] and nowadays cities compete with each other for a suitable place within global economic networks. Many mid-scale cities faced a sudden growth with fast transformations; different types of gentrification, removal of industry, housing boom, historic cities turning into open-air museums, global online services, co-working spaces, new generation shopping malls[6], third wave coffee places, artisanal food, designers’ markets, same brands, same movie posters and outcomes of the same design trends on every scale of production… To sell all, what is considered original, in order to be able to purchase all the similarities. When Walter Benjamin wrote on the loss of the aura of artworks in times of mechanical reproduction; he perhaps didn’t foresee that visual culture in the urban space would dominate almost all climatic, social, historical characteristics of the cities[7] and that places would start losing their auras in times of digital reproduction. In 2014, the 14th Venice Architecture Biennial[8] was debating how modernism eliminated the different national characteristics in architecture.

Mid-20th century modernism started shaping the developing financial centres of the cities. Post-war modern housing created the identity of most European, North-American and Soviet cities’ suburbs. With the neoliberal turn, the architecture and urban design disciplines, which were already struggling with criticism from within and without and coming up with revisions of the high modernism, now had the chance to grow in different ways, in cooperation with the corporate, private capital. Through the first 30 years of the neoliberalism, new tools were invented to align state and corporate interests[9] and architecture drifted away from its socially engaged position. There were no more suburban mass-housing projects, mat-buildings[10], walking cities[11] or the rest of the diverse set of utopian approaches. They were replaced by theoretic pursuits in architecture, perhaps less concerned with the social dynamics[12]. New types of places such as condominiums, transportation hubs, new art centres, new office spaces, transformation of brownfields and building luxury accommodations became the common practice and in time they dominated the urban space.

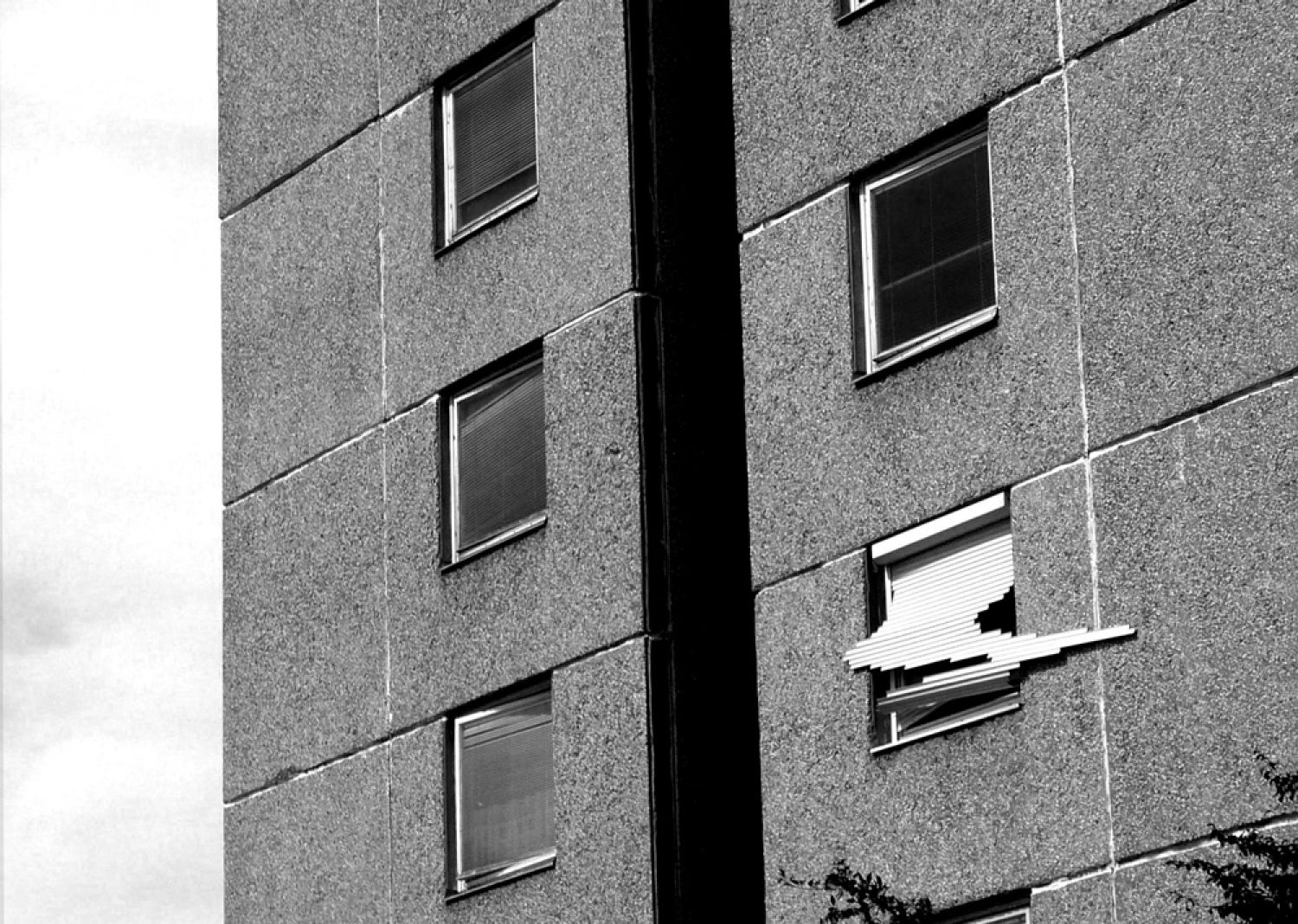

While the «world-class cities» were turning into similar places with the fast globalisation, in these last decades contemporary publications, exhibitions, and biennials, important platforms of discussion[13] for architecture and urbanism, have been focusing more and more on spaces, which were not signature buildings of star architects. The scope of «architecture without architects», since its use by Bernard Rudofsky in 1964, to name an exhibition in MoMA and the accompanying book; changed a lot: from a compilation of vernacular architecture examples, which show the diversity of living conditions, from different times and geographies (which he calls a «non-pedigreed» architecture, that we need in order to «freeing ourselves from our narrow world of official and commercial architecture»[14]) to images, which tell us a lot about the living conditions of millions of people. The images were taken perhaps in Mumbai or Caracas, Cairo or Istanbul: if we are not familiar with the places, we can still try to make a rough guess. Sometimes the blocks in the picture are from post-Soviet geographies of Eastern Europe or perfectly preserved outskirts of a German city. Sometimes these landscapes are considered ugly[15]; however, the tower block and the squatter possess some sort of aesthetics and charm, so they end up being the subject of countless research and artistic works.

Nicolai Ouroussoff, the critic of architecture for the New York Times for almost a decade, described the interest of the young designers in the post-war architecture, especially in brutalist buildings, as a reaction to the contemporary, which he describes as: «the saccharine Disney-inspired structures of today[16]». A video by Urban-Think Tank on Mumbai shows Alfredo Brillembourg, one of the founders of the group, walking on the streets of the city and comparing the so-called slum neighbourhood to a modernist block in the same scene. Brillembourg – in accordance with his words on urban elements such as highways and greenbelts, reminding the CIAM principles; says that he finds the «village culture much more interesting»[17]. It seems like while on the one side the monumental examples of design, of «architecture», still keep their grounds, on the other there are the vernacular, the village, the not-designed, the ones without architects… Two sources of authenticity or perhaps inspiration are represented as the thesis and antithesis of one another.

The 18th century European aesthetics were romanticizing the wild nature and the man-made ruins as corresponding elements[18]. Andreas Huyssen[19] wrote, on Piranesi's famous engravings, that in his works the incomplete or decayed architecture is the base of its authenticity, its genuineness. This tendency was reversed in the 20th century and the proud representations of big constructions, mass-production, works of engineering such as dams and bridges that became symbols of a triumph over nature. They were materializing a belief in a better society, achieved through technology. It was a trade of natural resources, the landscape, the trees and all the romantic elements of a previous era with progress, energy, and industrial development[20]. In the post-industrial society, these modernist monuments are haunted by a feeling of nostalgia[21]. Nostalgia is an insurgent act against linear progress[22] which is inherent to modernist thought. Svetlana Boym explains the nostalgic perspective as one, that «(…) desires to turn history into private or collective mythology, to revisit time like space, refusing to surrender to the irreversibility of time that plagues the human condition.[23]»

If we go back to the human condition, the vertical slums, the slummed modern, the squatted/appropriated relics of a previous time (such as the famous Torre de David[24] in Caracas, Venezuela or The Grande Hotel[25] in Beira, Mozambique) are the synthesis of a former period in architecture (considered to be the big failure and something completely contemporary, alive and unfinished) with something that architects or planners aimed at but never managed to design. The reasons why the architecture discipline is magnetized by these examples is very well articulated in an article[26], published in The Funambulist magazine:

«(…) what seems to fascinate us in the architectures without architects, is the degree of intensity in which life unfolds itself at every level. Self-construction provides a complexity of material and spaces in a mix of voluntarism and fortuitousness. The density of population forces people to communicate and negotiate social protocols. The multitudes of needs trigger a local economy based on tinkering and sometimes hijacking processes. The very existence of such architectures provides a strong political stand towards its surrounding. The otherness of the territory allows a different legal and behavioral system to articulate itself. All those elements – and probably much more as well – offer something that no architect is able to think and plan. (S)he can only throw here and there in his design and construction few catalysts, hoping that they will trigger situations in which life could unfold.»

This quote recalls the definition of «life-enhancing architecture» by Juhani Pallasmaa in his book Eyes of the Skin[27], first published in 1996, where he wrote that, perceived by all our senses, it creates a blended combination of how we perceive ourselves and of how we perceive the world. In the book he repeats that an architecture (in his case the reflective glass façade), that doesn’t let the users/visitors/inhabitants question and feel the reality and the self and leaves them unaffected and unmoved and creates a feeling of alienation is «an insincere architecture»; one that doesn’t allow for an existential experience, instead utilizing strategies of «instant persuasion»[28].

***

Neither easily persuaded by the previous strategies in architecture and urbanism, nor with the contemporary conditions of the cities, the exhibitions, publications and artworks dealing with the urbanization, have been looking for systems, organisations, complicated networks of relationships. Designers, researchers, and curators often produce romanticized representations of the existing and for the discipline of architecture a big part of this curiosity lies within reckoning with the past, a tool to criticize the big narratives, the «auteur»isms. These landscapes, as syntheses of modernist ideologies and the nature of contemporary social dynamics are clearly promising the initial claim of architecture which was to represent its own time and evolving with life itself. Reinhold Martin[29] wrote that, although the repressed utopian ghost is haunting the postmodern, it is actually characterizing it. For global cities, there is this similar relationship between the repressed and the repetition. What the signature buildings did to the global city centres is being refused by many young architects. The antithesis of the late commercial architecture: the spaces which are dynamic, complicated or so-called organic contain vast numbers of components of a more problematic urban condition. Architecture and urbanism or any singular discipline have only limited part in its emergence. The artistic or the design research has been dealing with ways of simplifying and explaining what is beyond our knowledge so far. But simultaneously many practices already recognize the architects’ role in a much crowded teamwork and a lot has been produced regarding participation, urban commons, shared knowledge models. By demystifying narratives regarding work, and by demystifying the grand consensus on the working conditions[30], the way space is being perceived and produced is changing continuously. With each shift, the definition of ugly is transforming and new aesthetic representations are appearing. The modernist monuments are not taken over by nature like it happened to classic monuments but with the social networks they are nevertheless ruined aesthetically.

Footnotes

- ^ Sontag, S. (2003). Regarding the Pain of Others. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- ^ https://www.theguardian.com/housing-network/2016/feb/15/ruin-porn-detroit-photography-city-homes

- ^ http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/urbanization/urban-rural.shtml

- ^ http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/news/population/world-urbanization-prospects-2014.html

- ^ Sharon Zukin’s collection of works is a major resource for understanding the effects of cultural production and comsuption on urban space but for a fast summary of the transformation of cities through neoliberal policies, exemplified through London and New York: Zukin, S. (1992). London and New York as global financial capitals. Global finance and urban living: A study of metropolitan change. Also Urry’s Tourist Gaze article is a milestone in understanding the transformative power of tourism on space. (The Tourist Gaze. Leisure and Travel in Contemporary Societies. [1990]. London: Sage Publications.)

- ^ https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2017/mar/16/malls-cities-become-one-and-same

- ^ https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2017-10-11/cities-and-suburbs-are-becoming-pretty-similar

- ^ https://www.domusweb.it/en/news/2013/01/25/fundamentals-rem-koolhaas-presents-his-biennale.html

- ^ https://newleftreview.org/II/53/david-harvey-the-right-to-the-city

- ^ https://www.architectural-review.com/essays/viewpoints/the-strategies-of-mat-building/8651102.article

- ^ https://www.moma.org/collection/works/814

- ^ Cowherd explains the critical approach in architecture in the US, developed by the strong influence of Peter Eisenman and Michael K. Hays in his article dated to 2009, very thoroughly. I want to refer to this phrase as strongly emphasised: «untainted by the impurities that might force compromise in the quest for a theoretically rigorous architecture».

- ^ Uneven Growth exhibition was opened in MoMA at the end of the year 2014 and Global Cities exhibition in 2007 in Tate Modern was an extension of the 10th Venice Biennial Cities. Architecture and Society. 4th Rotterdam Architecture Biennial called the Open City was also inviting the audience to discuss inclusive design in 2009.

- ^ Rudofsky, B. (1964). Architecture without architects: a short introduction to non-pedigreed architecture. UNM Press.

- ^ An article published in Calvert Journal on Soviet landscapes in photography, mentions that photographer Max Sher wants to aestheticize, what is considered ugly. https://www.calvertjournal.com/features/show/9868/post-soviet-visions-tower-block-photography-architecture

- ^ https://www.nytimes.com/2009/03/19/arts/design/19robi.html

- ^ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_4ELdcVZgYk

- ^ DeSilvey, C., & Edensor, T. (2013). «Reckoning with ruins». Progress in Human Geography, 37(4), 465-485.

- ^ Huyssen, A. (2006). «Nostalgia for ruins» in Grey Room, 6-21.

- ^ Kaika, M. (2006). «Dams as symbols of modernization: The urbanization of nature between geographical imagination and materiality» in Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 96(2), 276-301.

- ^ Buck-Morss, S. (2002). Dreamworld and catastrophe: the passing of mass utopia in East and West. MIT press.

- ^ Boym, S. (2007). «Nostalgia and its discontents» in The Hedgehog Review, 9(2), 7-19.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ http://torredavid.com/

- ^ https://failedarchitecture.com/once-a-colonial-hotel-now-an-inhabited-ruin/

- ^ https://thefunambulist.net/architectural-projects/architecture-without-architects-why-do-architects-dream-of-a-world-without-them#more-11221

- ^ Pallasmaa, J. (2012). The eyes of the skin: architecture and the senses. John Wiley & Sons.

- ^ Ibid., pp. 30-31.

- ^ Martin, R. (2010). Utopia's ghost: architecture and postmodernism, again. Minnesota Press.

- ^ http://www.harvarddesignmagazine.org/issues/46/refusal-after-refusal