Prôsopon explosante-fixe

Katherine Sirois

«La beauté convulsive sera érotique-voilée,

explosante-fixe, magique-circonstancielle, ou ne sera pas».

André Breton, L’Amour fou, 1937

The Greek notion of prôsopon designates and groups indifferently the mask and the artificial figure of the inanimate objects, as well as the face of the living man or those of the ancestors given by means of the image. Prôsopon also refers to the action of seeing, of looking and of showing oneself, of presenting oneself to the sight of others. It is that which «faces» and through which it is possible to «put in presence», that renders a confrontation and a relational dynamic possible between two figures, two objects, two subjects or between an object and a subject.

Furthermore, prosôpopoeia or prosopopoeia refers to the act of personifying and animating artificial figures through the incarnation of absent characters or supernatural entities such as divinities, powers of nature or ancestors. In the theatre, the motionless and frozen mask is progressively animated, both by the body movements performed by the actor and by the oral descriptions of the emotions and feelings experienced during the narration by the characters. Movements of the actors and narrative content combine, thus giving rise to the visualization for the spectators of facial expressions, which has the effect of transforming, during the representation, the visual aspect of the masks. Thus animated and invested with expressiveness and life, the mask becomes diegetic, it is the mask of the muthos.

The personification of the masks that takes place in the theatrical setting, the phenomenon of transformation that takes place in them – their change in pulsation, movement and expressivity from the initial stiffness and fixity – are also characteristic phenomena of masks from ritual ceremonies and initiations that have taken place in traditional societies that ethnologists, anthropologists and art historians have been able to observe and whose complex and versatile symbolism they tried to understand throughout the 20th century. These phenomena, peculiar to masks and objects which have undergone a ritual consecration (which is equivalent to an operation of transmission of an invisible vital force, the investment of a power, which equals the process of incarnation and / or of metamorphosis), are realized in particular by staging the founding myths, by the dynamism and kinetic phases of the dances performed by the bearers of the masks and, in this case as in that of the theatre, by the participation and the imaginal investment of the spectators.

Therefore, whether they were made to be worn or not, whether they were masks of Greek, Roman or Japanese theatre, masks of religious ceremonies from China or Oceania, protagonist objects in the conduct of rites or celebrations devoted to the gods or to the ancestors, these objects, besides the potentiality of animation and setting in motion that they deploy, are also characterized by their ambivalence and by their signifying and acting complexity. This complexity is manifested by their functions of transformation and incarnation that consist in transforming bearers and celebrants or in making visible and present among human communities, invisible entities, bringing out and perpetuating mythical characters and events. Thus, the operational power of transformation works in both ways. This bi-directional phenomenon of inter-affection is assimilated to what we may call a reciprocal impregnation.

With these ceremonial objects, we are certainly dealing with what Rudolf Otto called the «complete Otherness», the ganz anderes, or with «the appearance of distance, no matter how close the thing that calls it forth», according to Benjamin’s definition of the aura[1]. The experience of radical strangeness extracts the subject from everyday life and from the level of ordinary consciousness. It takes possession of him by the awakening of the distance of his gaze in the object that is looked at[2].The «complete Otherness» is what exceeds and what, consequently, cannot be grasped, limited or framed by conceptual categories and definitions. These objects, because they are connected to a higher order of reality – whence the irreducibility of the mystery which often characterizes them – are then capable, in their context of origin, above all, of causing something to emerge as a radical experience of the sacred[3].

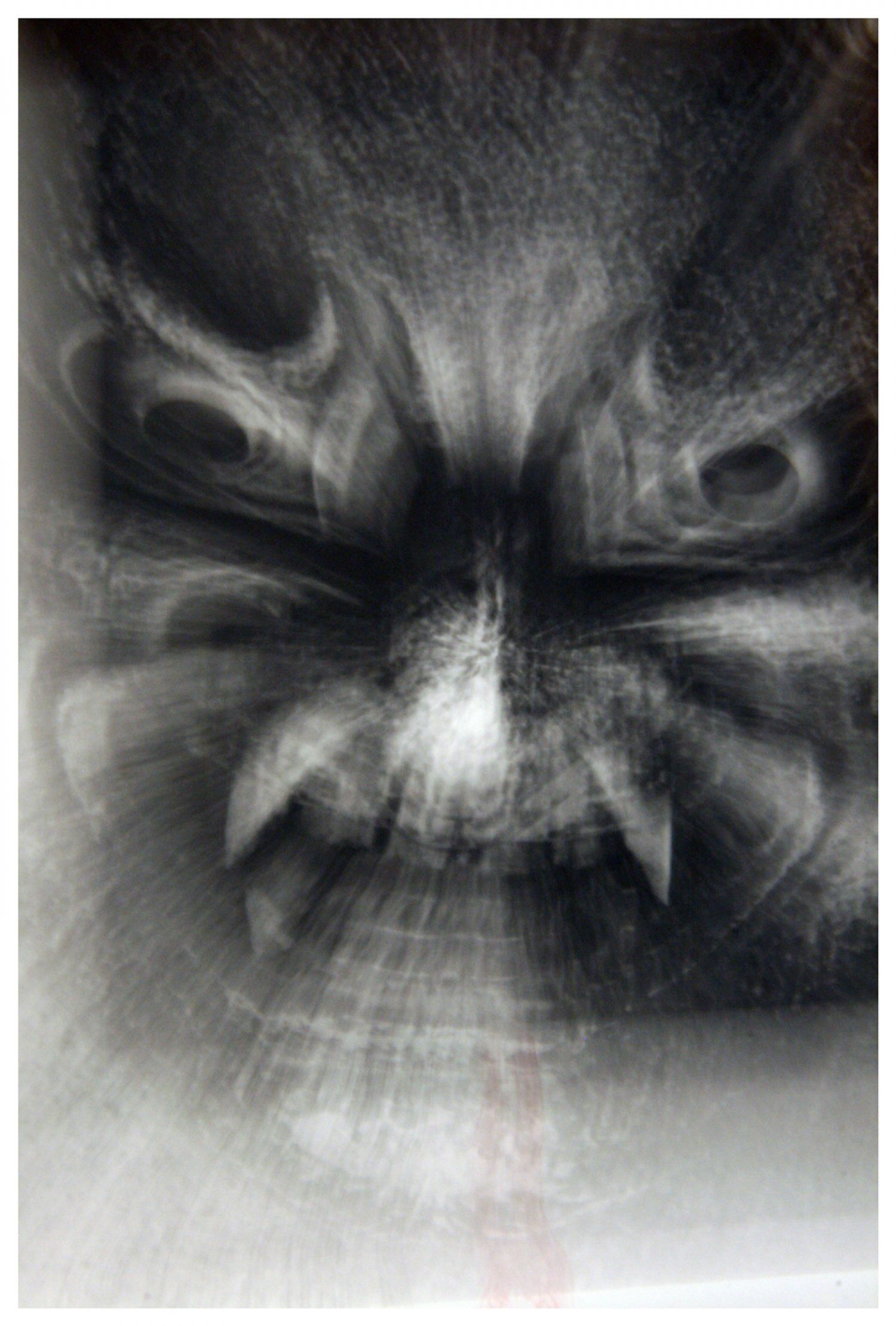

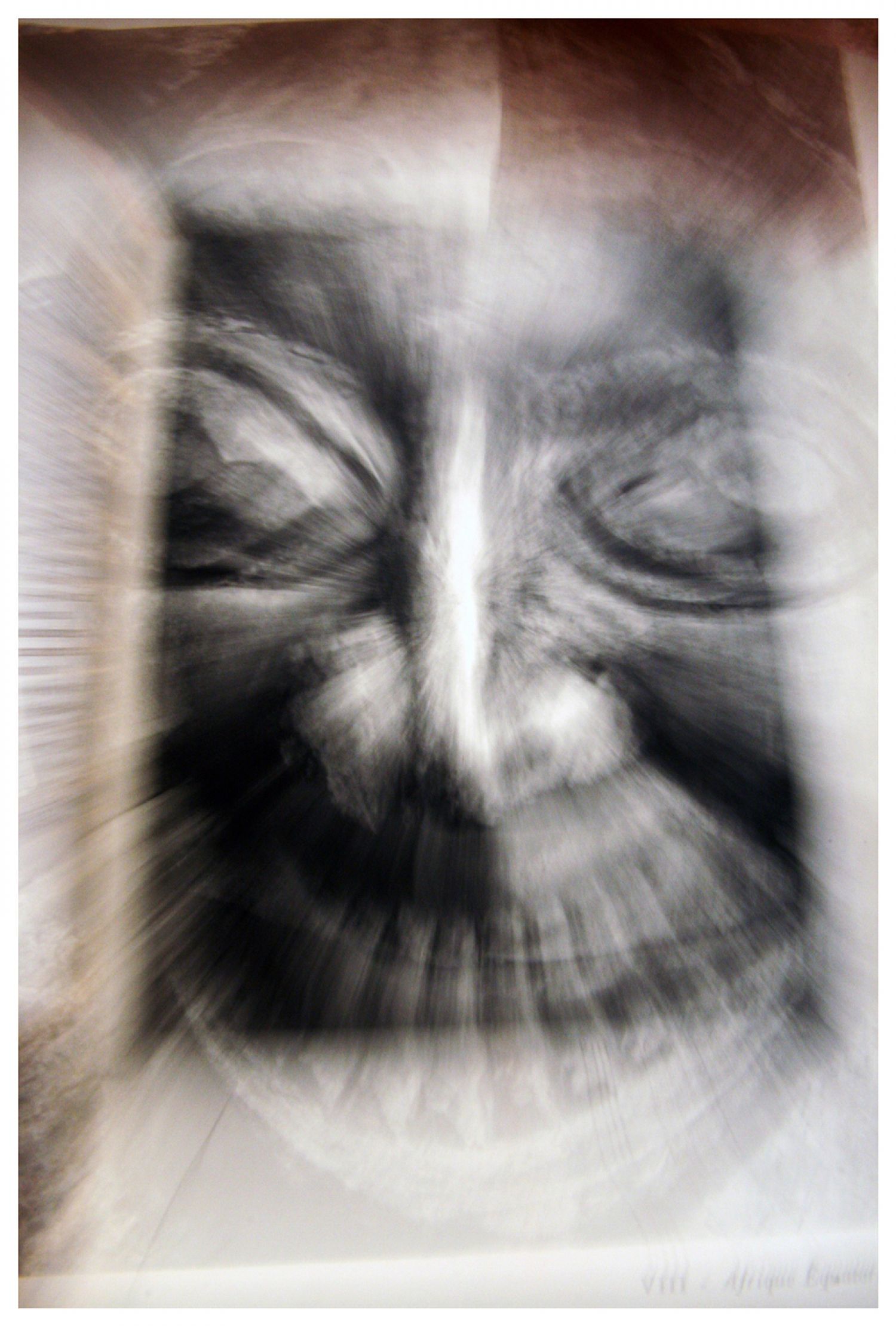

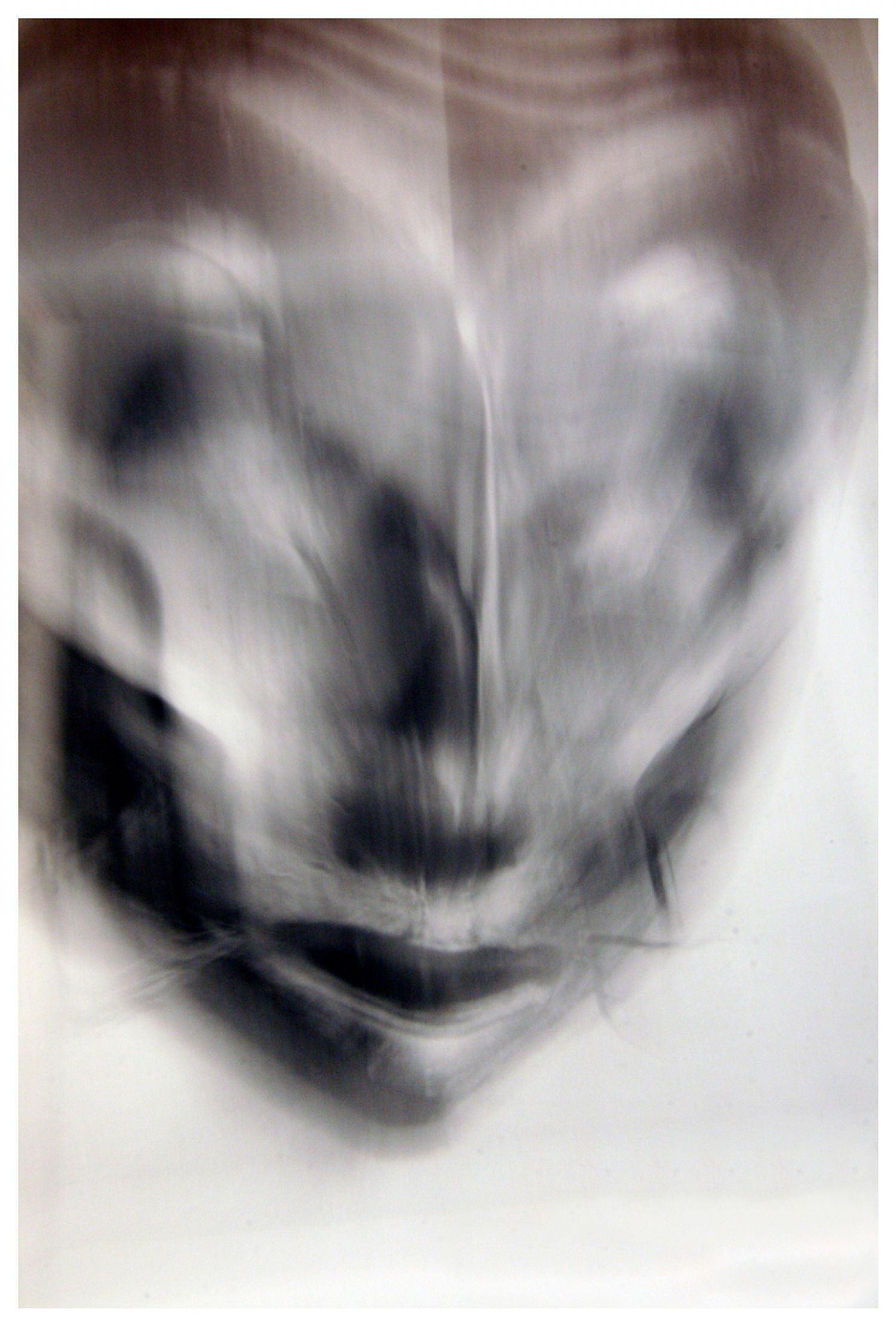

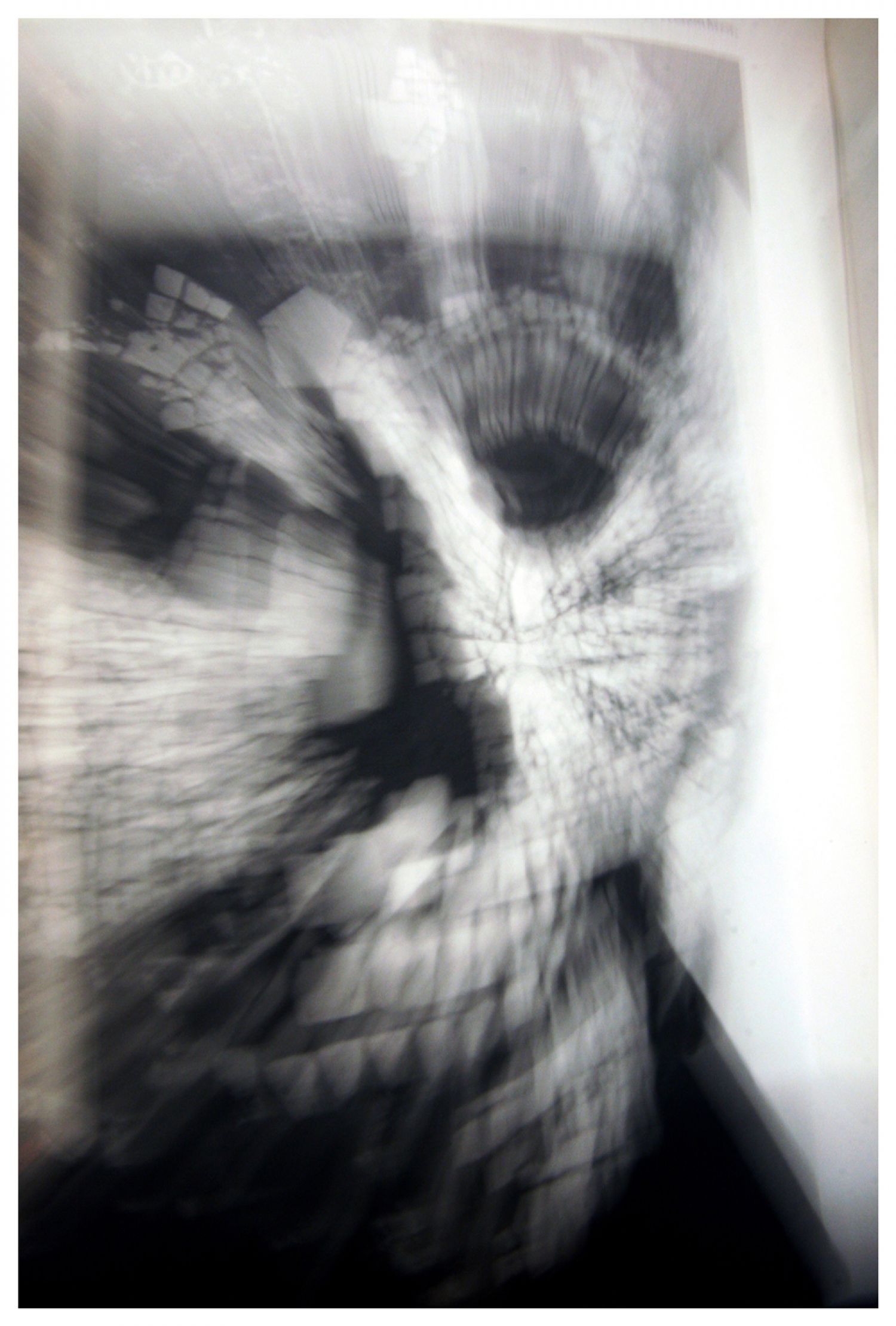

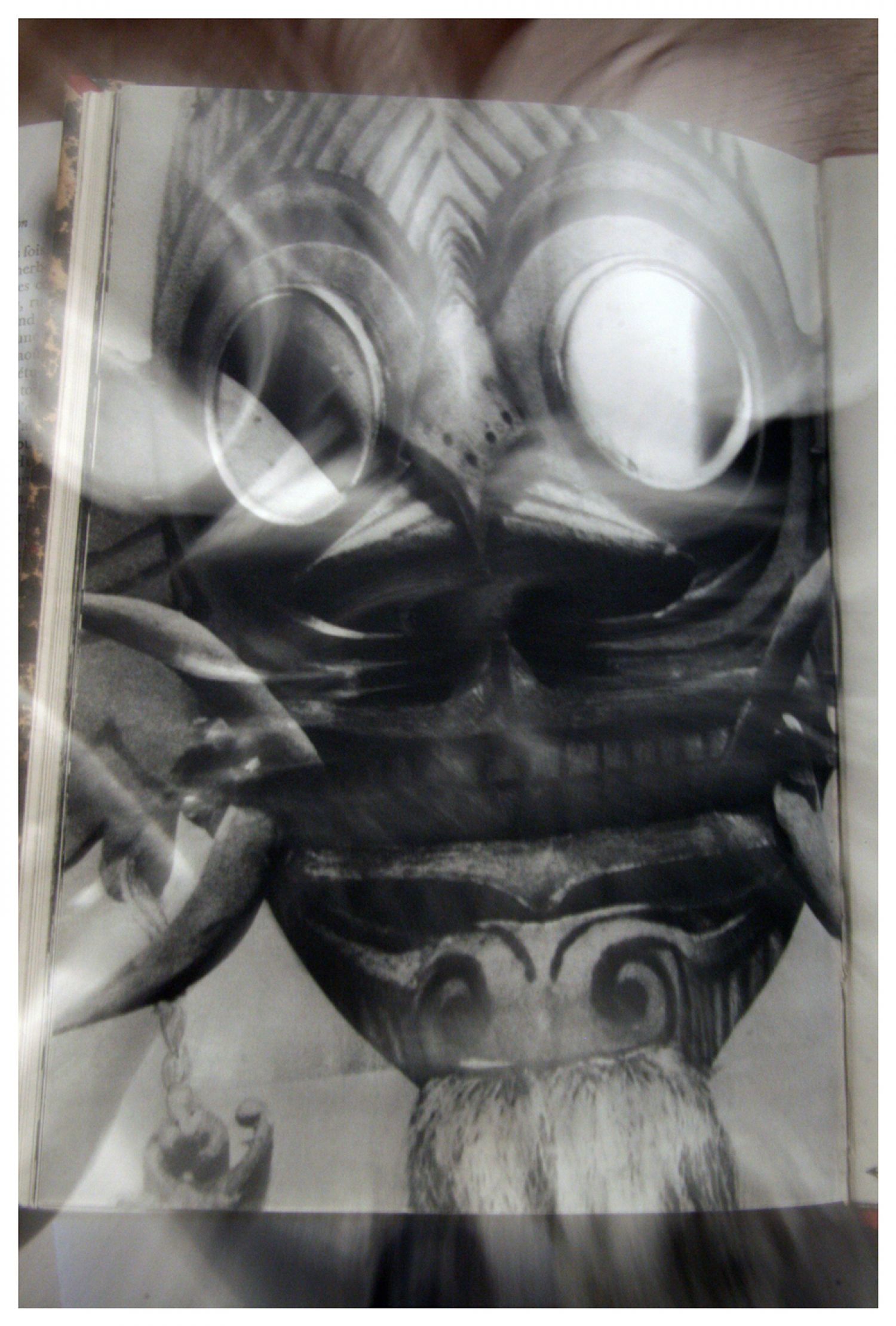

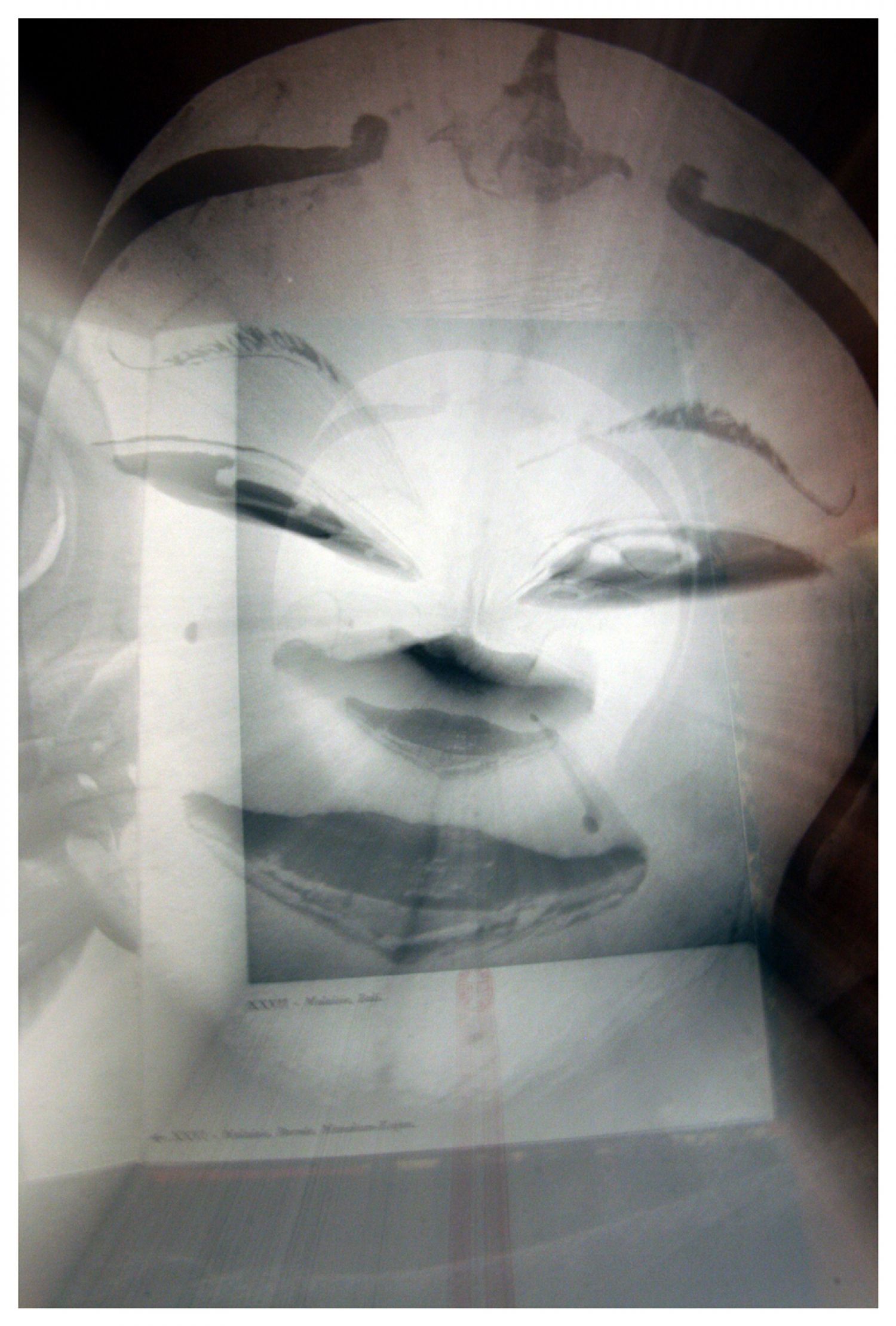

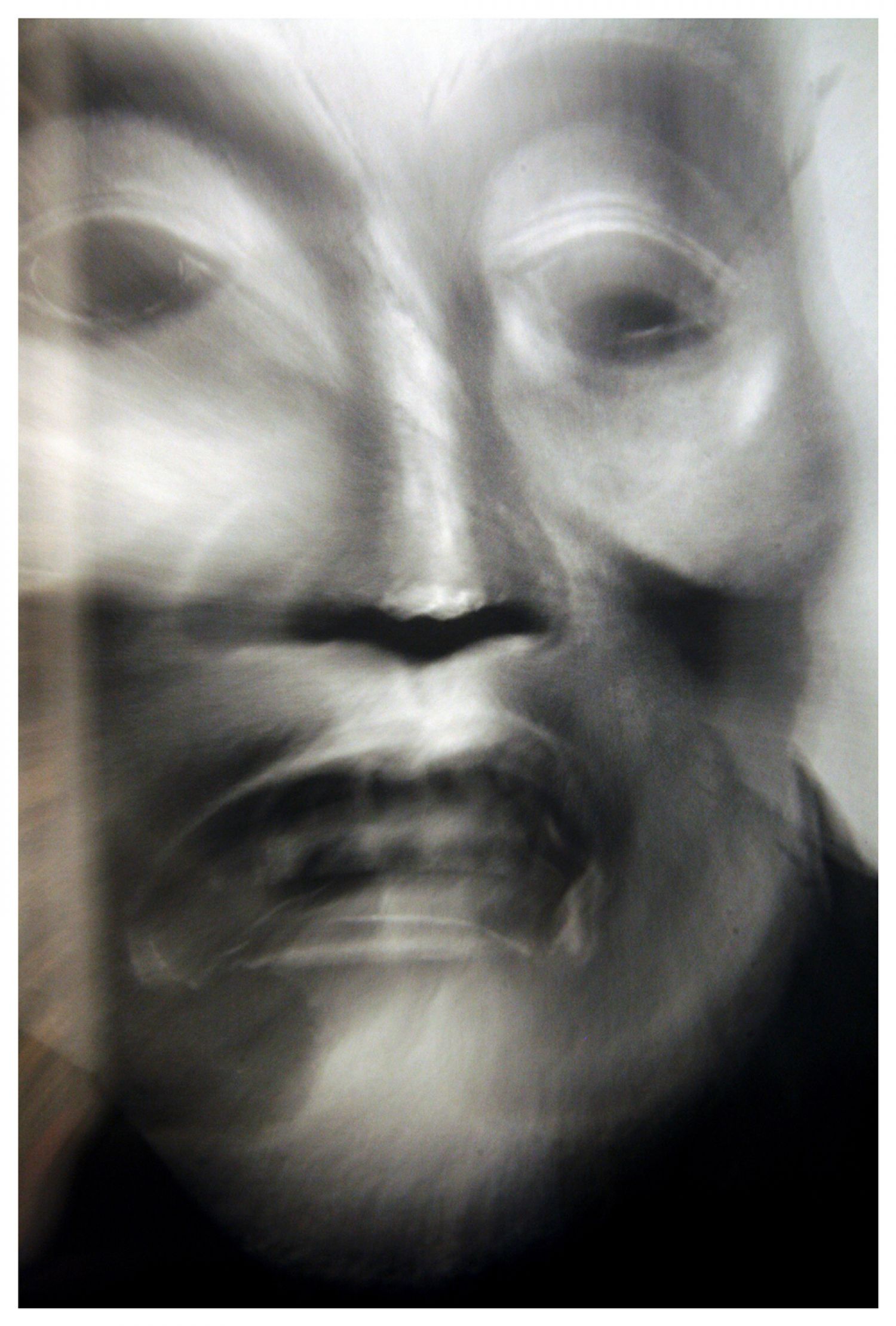

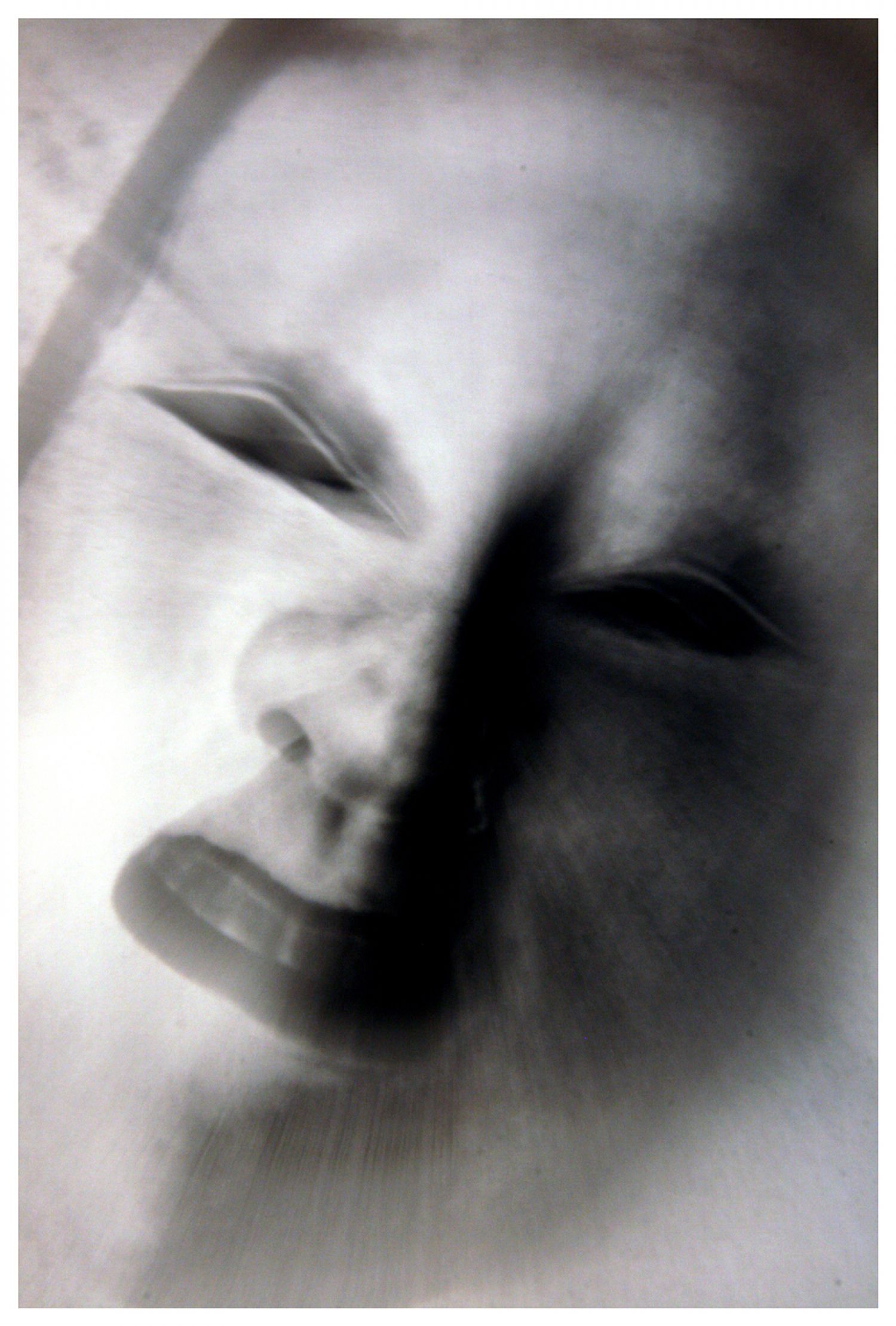

Anticipating Claude Lévi-Strauss’ considerations, published in 1979 in The Way of the Masks, I.L. Schneider wrote in 1951, in a book entitled Les masques primitifs: «These masks, now hanging side by side in museums, dead, do not let us suspect the power they develop in action»[4]. In this work, Schneider renounced to conventional photography to approach the mystery of the fixed features and give them back the most intense and impressive phase of activity. Thus, by shooting diagonally, by the use of blur and close-up, by installing some instability, by decentring in width and height, he stressed the expressive force of the masks, enhancing their impact on the reader viewer. He intended to impart movement and dynamism – to doubly fixed and circumscribed objects – as living portraits taken from life, and thus to give an impression of masks on the move, as if they were precipitating on the photographer[5].

In this series I pushed Schneider's ideas further from the photographs he published in Primitive Masks, accentuating the effects of motion and blur, introducing radiation, appearance, destabilization, duplication, overflow and explosion. This way, one sees masks in flight, masks dancing in space, masks striking with expressiveness, exploding at high speed the frame where, despite Schneider, they remained, frozen and limited.

But, in spite of the palimpsest of found objects and the discovery of images of objects that can thus be superimposed, and in spite of its circumstantial and operative magic, the paradox is still intact. For though it is «explosive», the photographic image of an object set in motion or not, will remain a spectral and ghostly image, like the masks themselves, once out of their context, emptied from their real and sacred power of action and transformation.

Between fixity and animation, the mystery remains.

Photography and Text by Katherine Sirois

Footnotes

- ^ Walter Benjamin, Arcades Project, translated by Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin, ed. Tiedemann, Cambridge Mass. 1999, p. 447. Or, according to the first definition of the Aura given by Benjamin in the Little History of Photography, (1931) «a strange weave of space and time: the unique appearance of a distance, however near it may be» / «Ein sonderbares Gespinst von Raum und Zeit: Einmalige Erscheinung einer Ferne, so nah sie sein mag» (Selected Writings, Cambridge, Mass. 1996-2003, 518). Cf. Miriam Bratu Hansen, «Benjamin’s Aura», in Critical Inquiry, 34, Winter 2008, pp. 336-375.

- ^ «Meine Definition der Aura als der Ferne des im Angeblickten erwachenden Blicks», Benjamin, Arcades Project, ibid., p. 314 / PW, 5 :1/ 396.

- ^ Rudolf Otto, Le Sacré. L’élément non rationnel dans l’idée du divin et sa relation avec le rationnel, translation from the German after the 18th edition by André Jundt, Paris, Payot, 1968 [1917].

- ^ Schneider, I. L., Masques primitifs, Paris, Les Iles d'Or, Plon, coll. «Psyché», 1951, sp.

- ^ Idem.