Poetics of Resistance

Marcelo Brodsky

Marcelo Brodsky’s Poetics of Resistance

Valentina Locatelli

Du darfst nicht sitzen und alles auf dich zukommen lassen. Du darfst dich vor allen Dingen nicht dem Gedanken hingeben, daß Mächtige über Dir sind, die doch alles bestimmen.

You must not sit and let that everything comes to you. Above all, you must not surrender to the thought that powerful people above determine everything.

Peter Weiss[1]

In 1981, in a passage of the interview given to Heinz Ludwig Arnold, German artist and writer Peter Weiss summarized the fundamental observation conveyed by his three-volume novel Die Ästhetik des Widerstands (The Aesthetic of Resistance, 1975–81) as follows: at any given moment in history―and, at that time, also in many Latin American countries ruled by dictatorships―people have always demonstrated a powerful drive to resist injustice and limitations to their freedom and, moved by a strange principle hope (“einen merkwürdigen Prinzip Hoffnung”), rise up in protest against coercive governments at the risk of their own lives and liberty.[2] Weiss’s book is a dramatized historical account of the proletarian resistance against fascism in the Europe of the late 1930s and into the Second World War. His message, however, is still relevant today and strongly resonates in Marcelo Brodsky’s latest art project, The Poetics of Resistance.

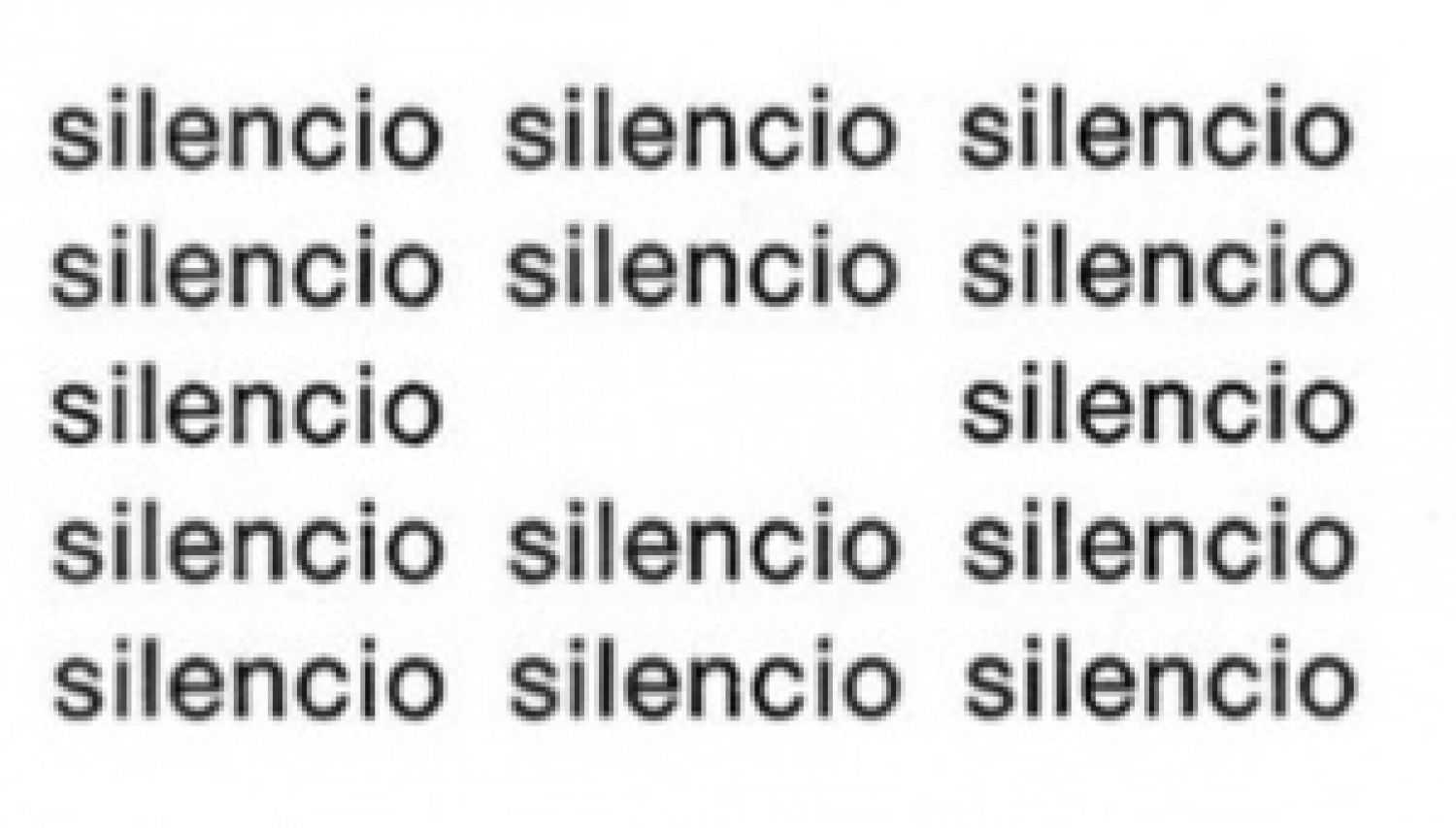

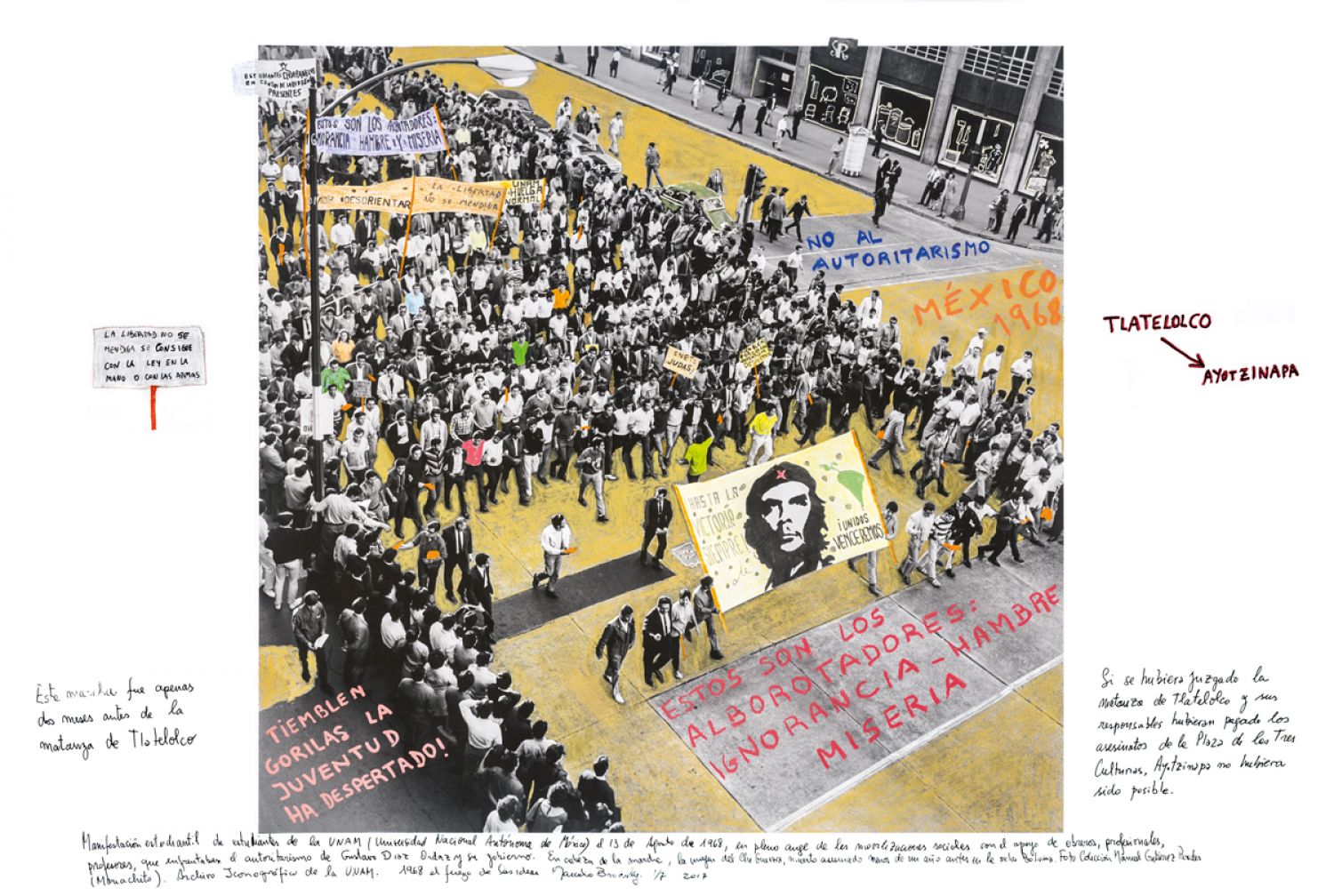

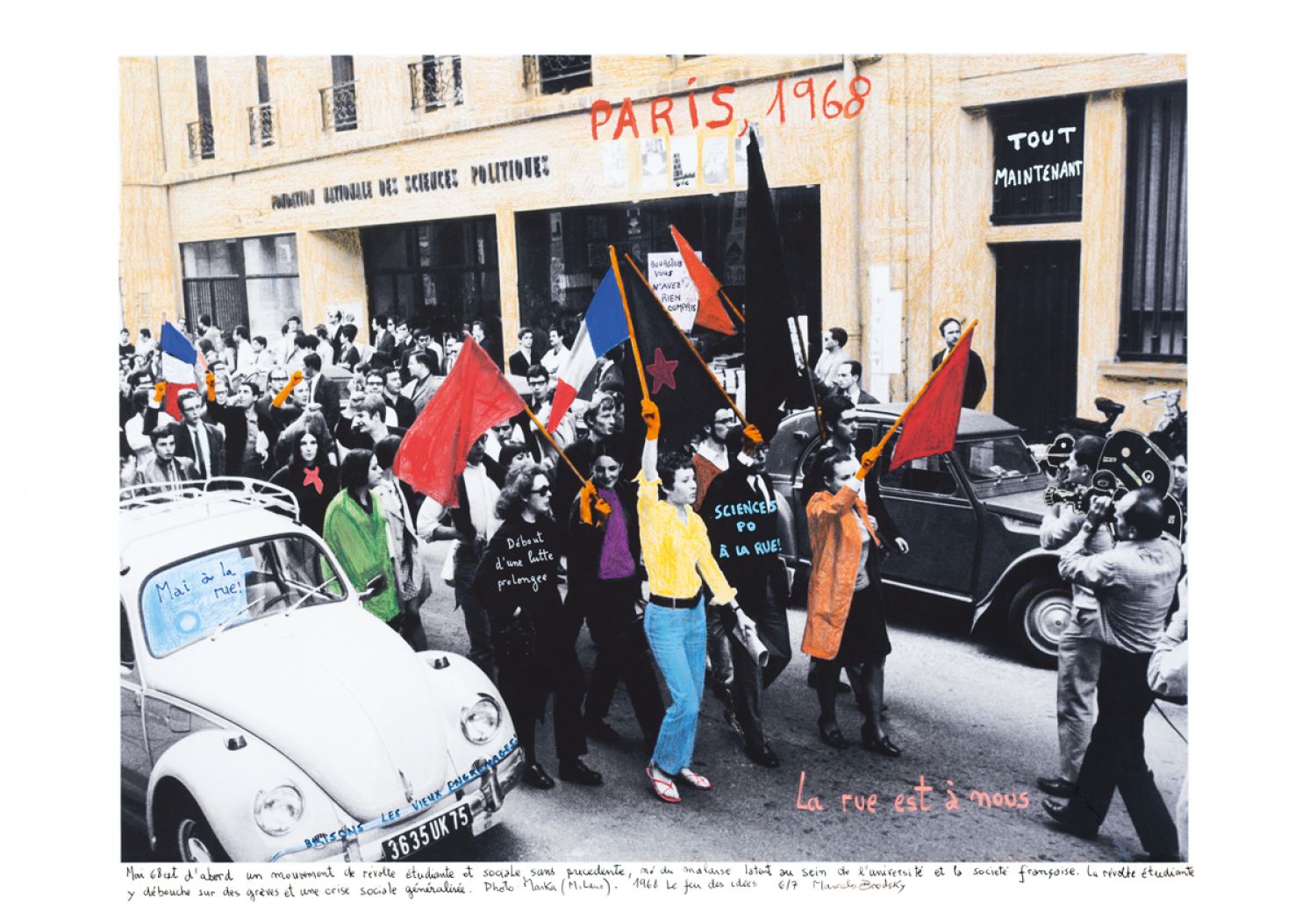

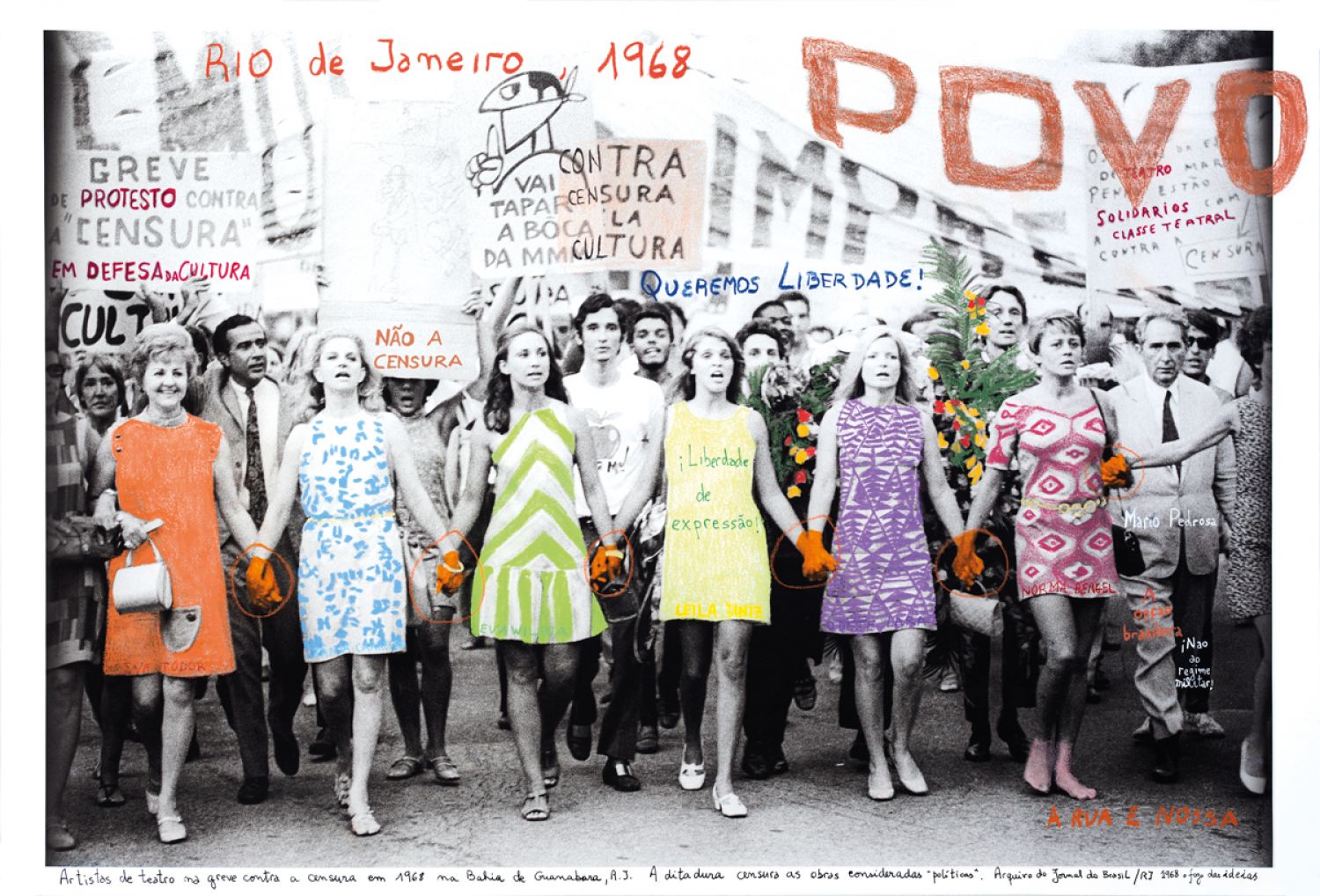

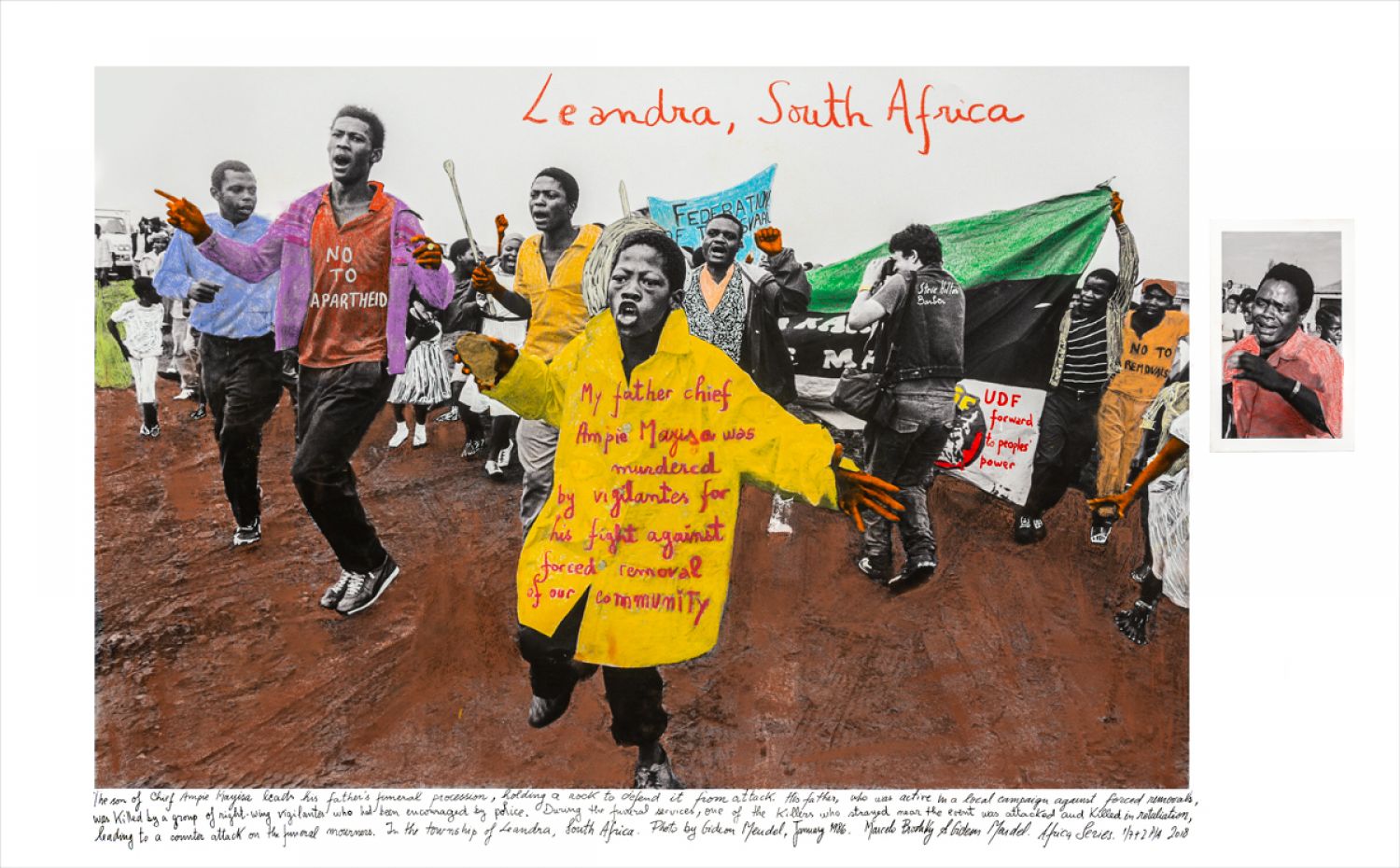

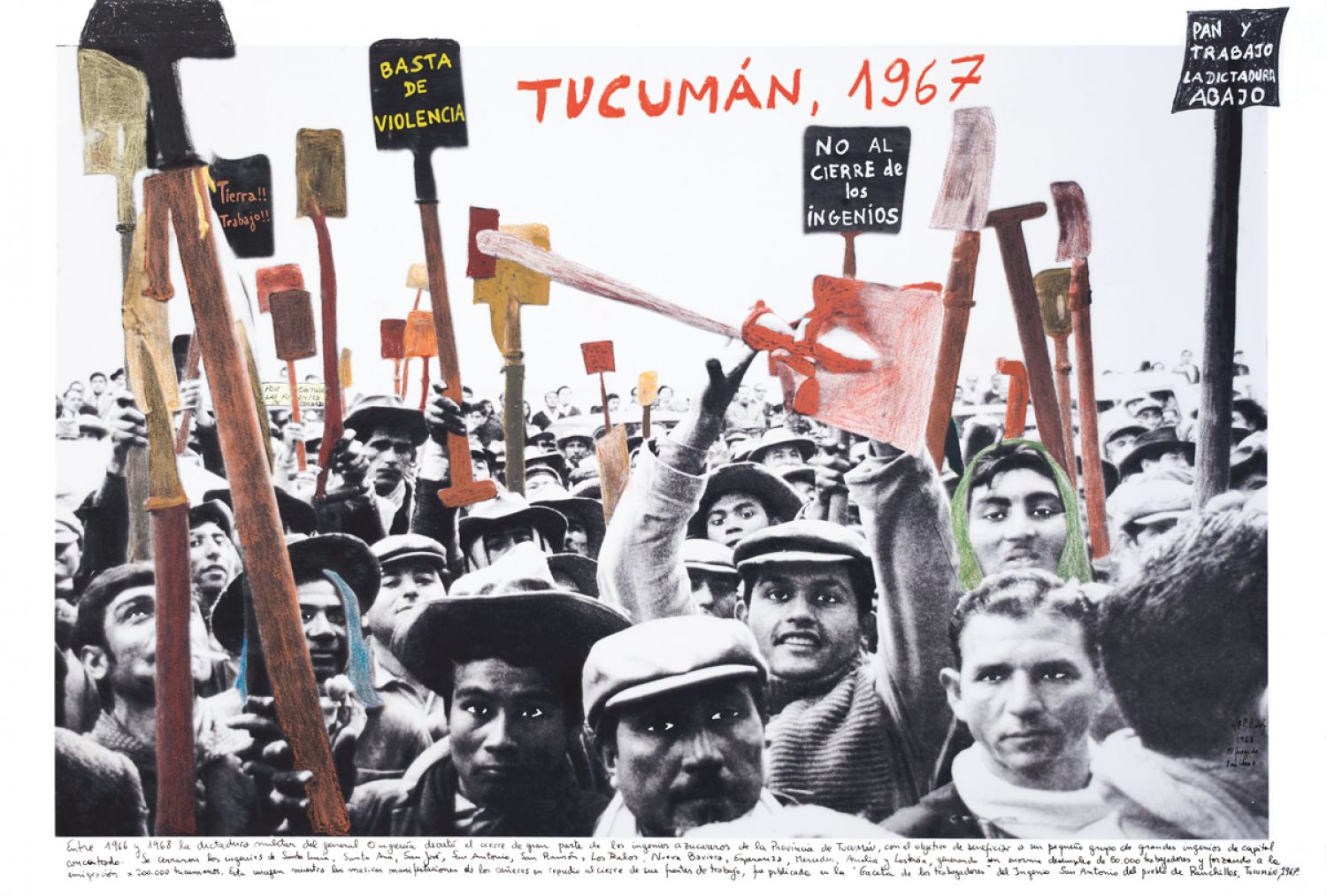

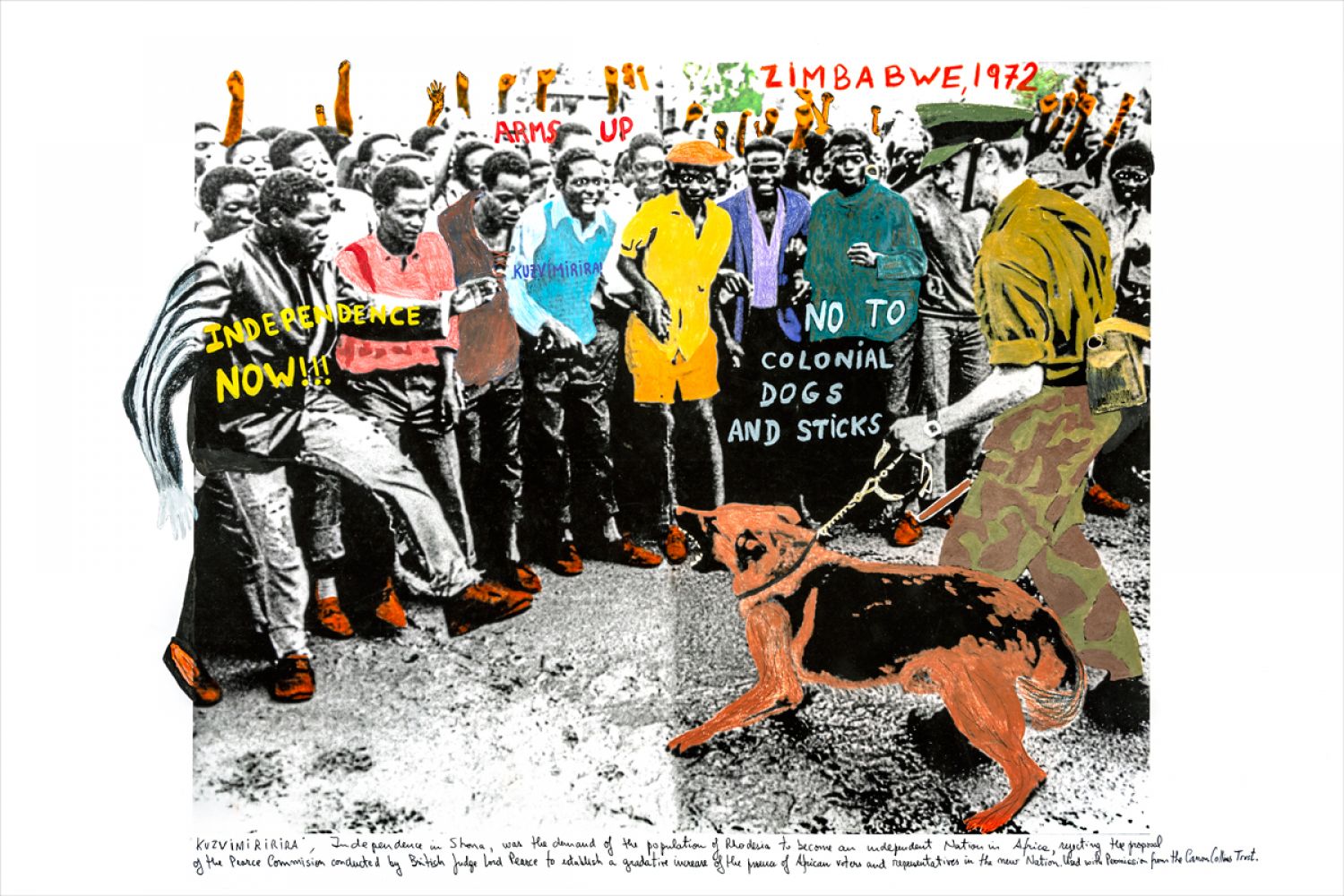

In his books, Weiss, departing from a description of the gigantomachy frieze of the Pergamon Altar in Berlin and its symbolic representation of the constant and ubiquitous presence of revolt and suffering in human history, put the emphasis primarily on aesthetics, that is on the visual experience of art, its educational potential for the viewer and the necessary role it plays in any revolution. Brodsky, on the other hand, addresses the notion of resistance first and foremost from the perspective of a poetic exercise. ‘Poetics’ is the theory of poetry and literary discourse, its origins in Western philosophy can be traced back to Aristoteles and his homonymous treatise (De Poetica, in the Latin translation). While the primary focus of poetics is set on the different components of the text, their interaction and the resulting effects they exert on the reader, poetics does not pertain only to poetry in verses but to any work of art which uses language. Interweaving text, image and colour, Brodsky’s «intervened photographs», as he defines them, exemplify this theoretical approach and become a poetic instrument of social awareness.

Brodsky is conscious of the power of both images and words. Born in Argentina in 1954, over the past five decades he has progressively developed a unique poetics based on the interaction of, mostly journalistic and archival, photographs and written annotations to achieve his objective: to activate personal and collective memory to communicate a message of resistance that may connect people across time and space. Working at the crossroads between visual arts, poetry and human rights activism, Brodsky’s practice is rooted in his personal history and direct dramatic experience of State-sponsored terror in Argentina. During the Argentine Military Dictatorship (1976–83), his best friend Martín Bercovich and his younger brother Fernando were abducted and disappeared in 1976 and 1979 respectively,[3] a traumatic event which prompted the artist to go into exile in Barcelona, where he lived until the period of military dictatorship in Argentina ended and democracy was restored.

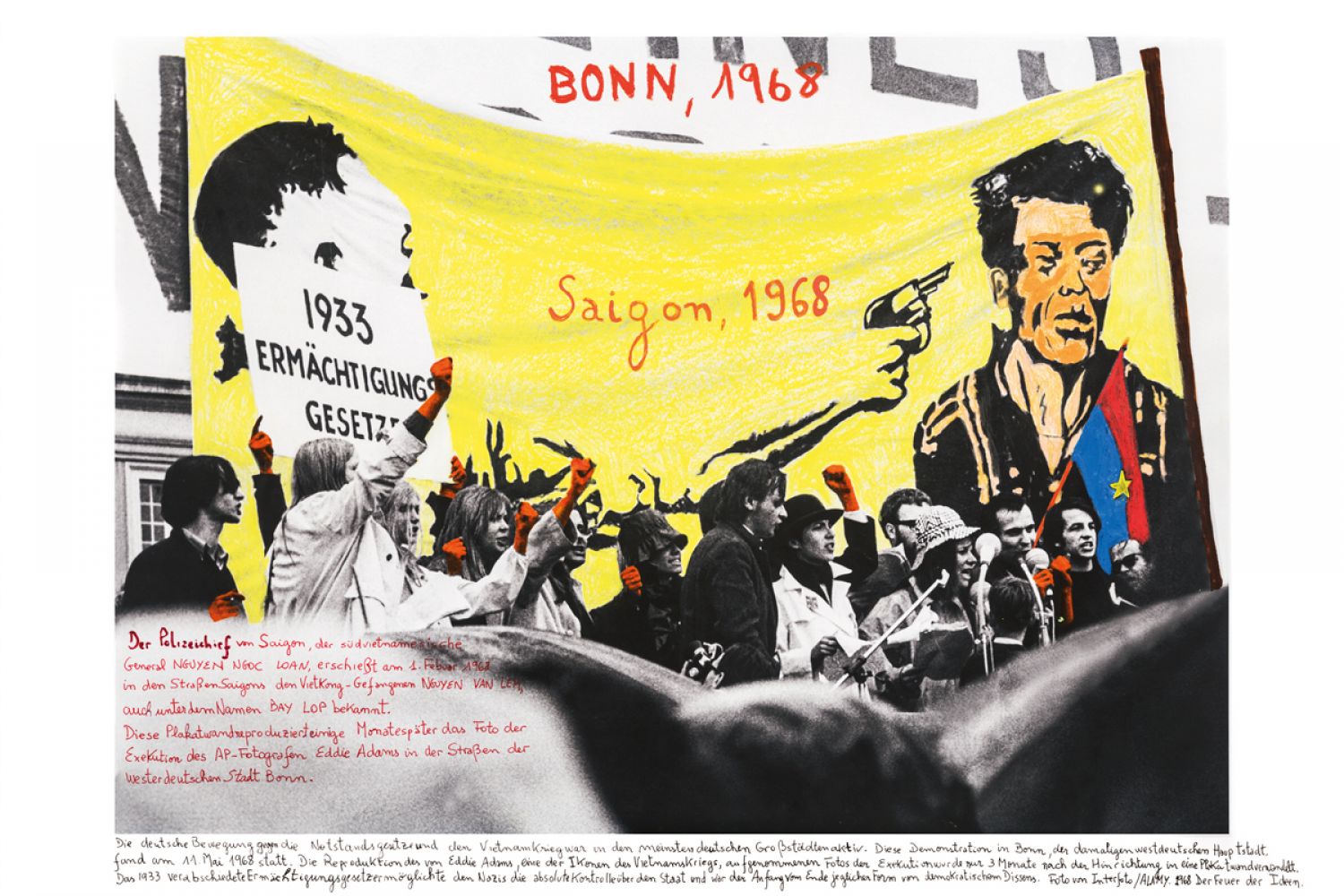

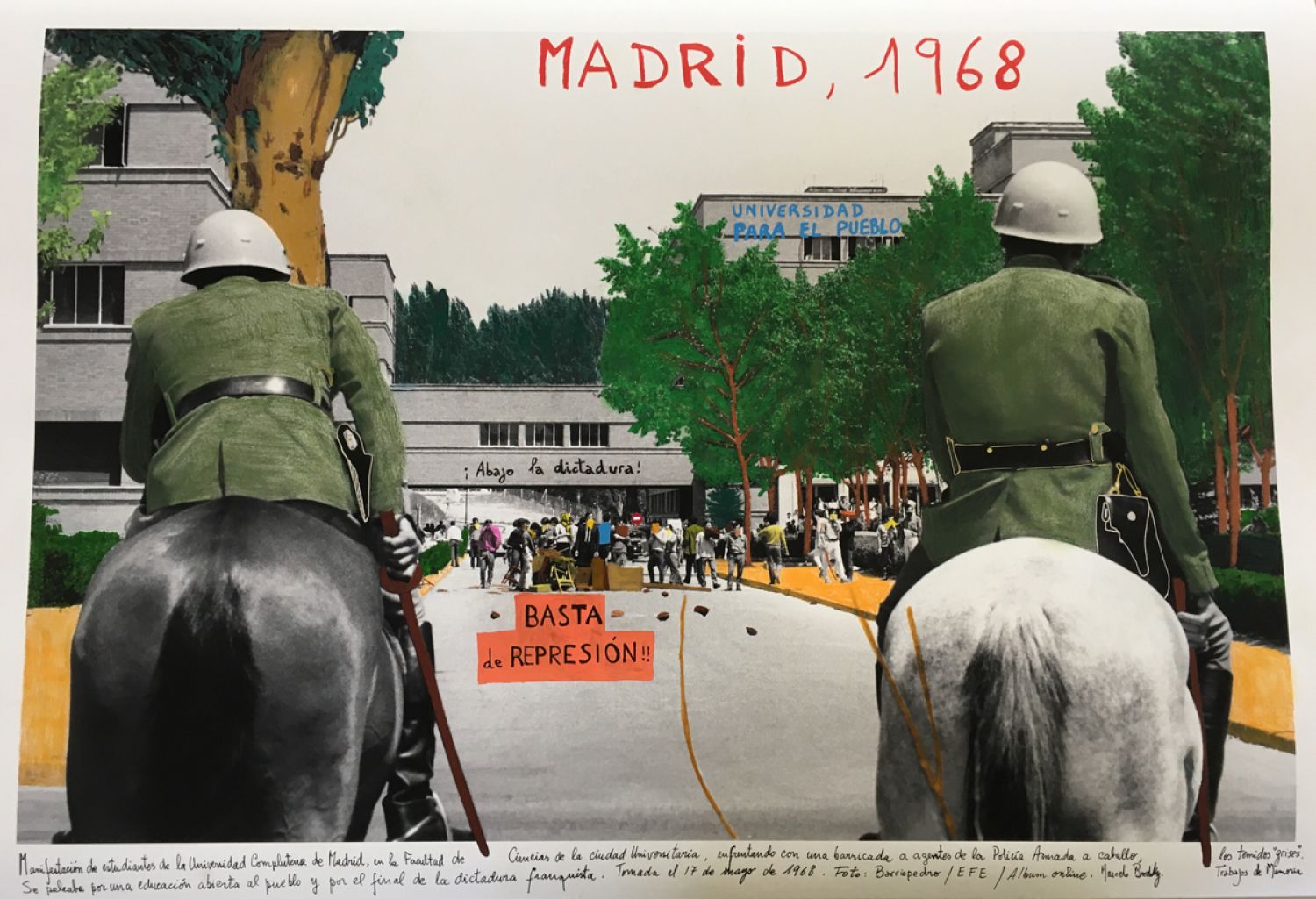

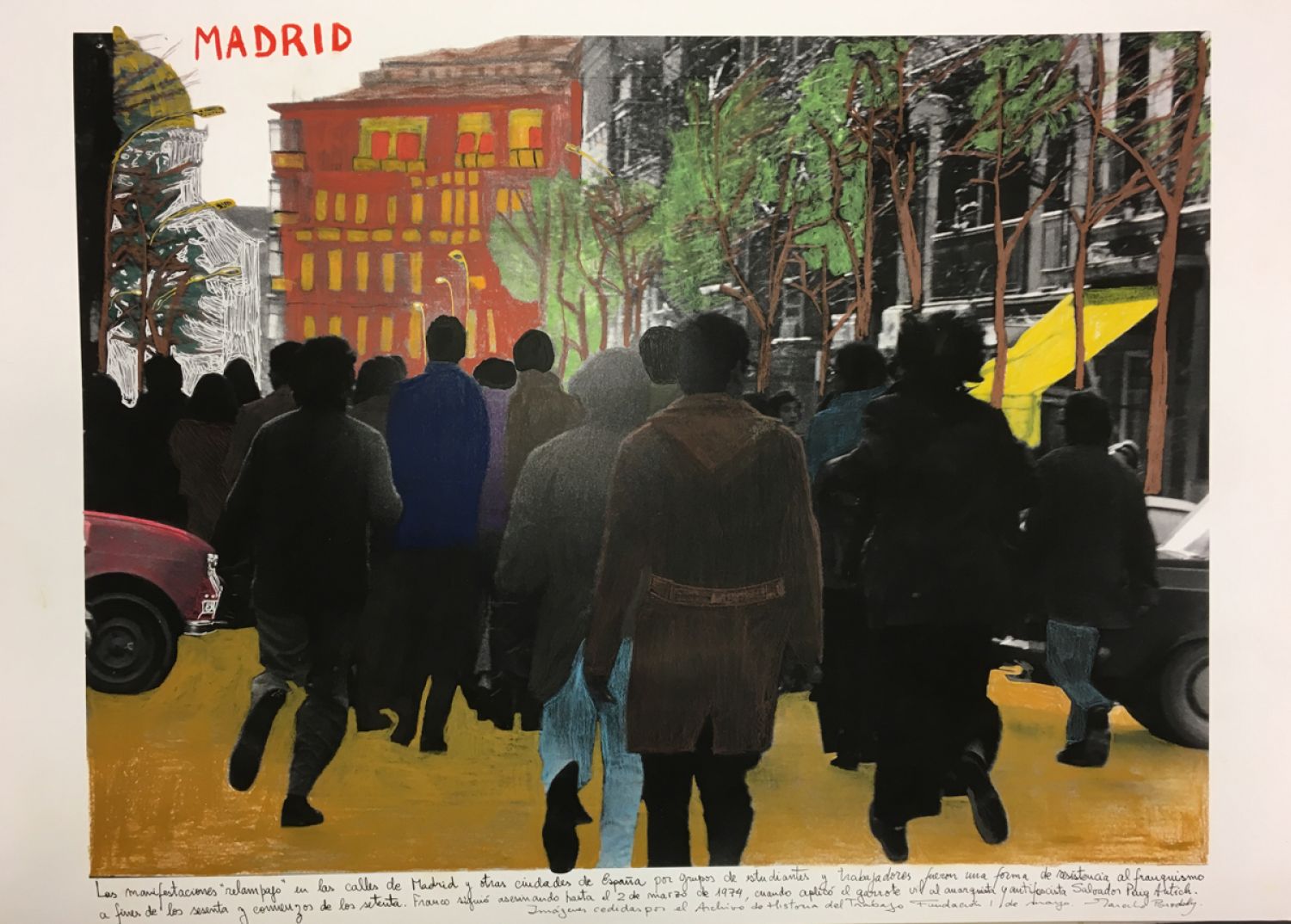

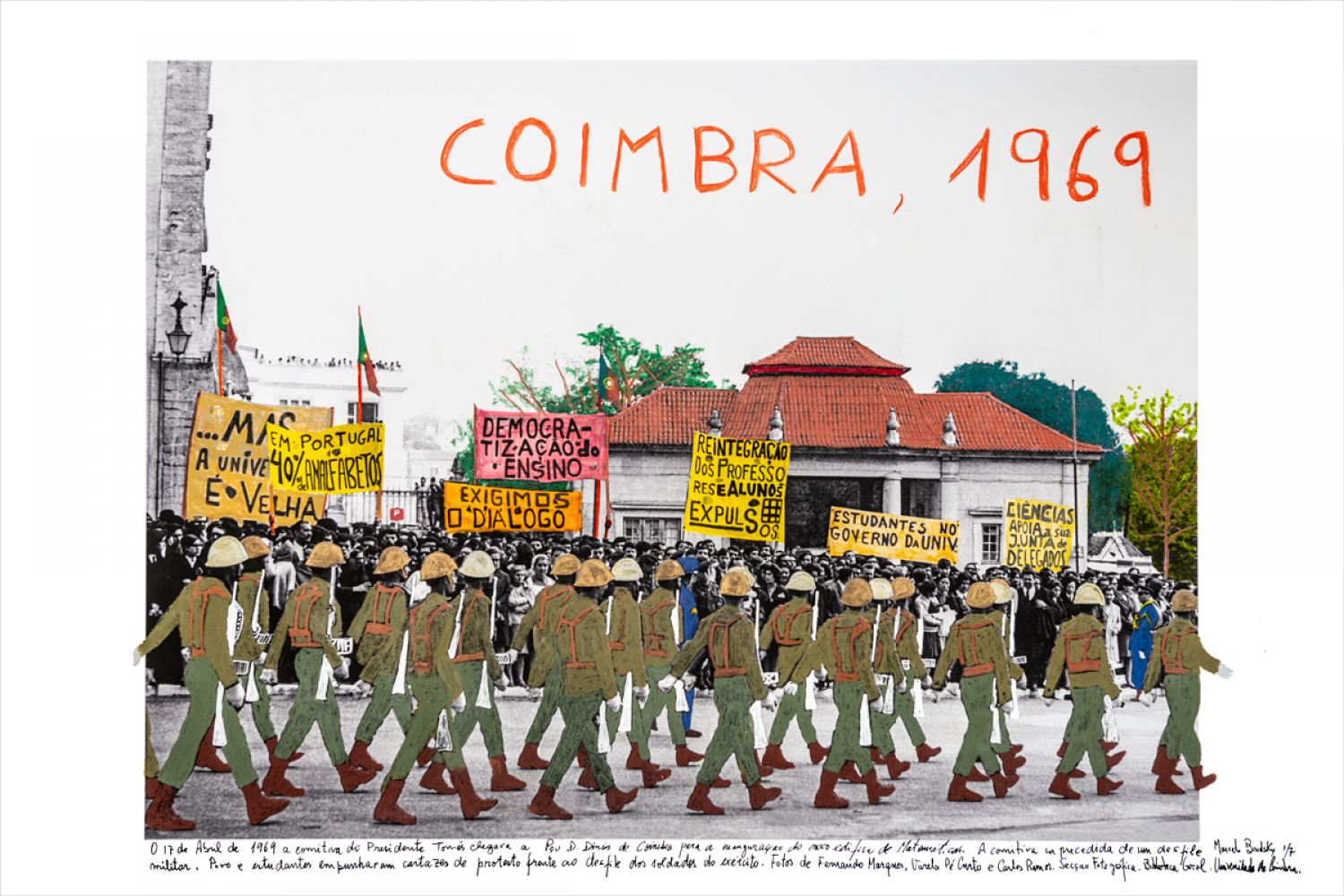

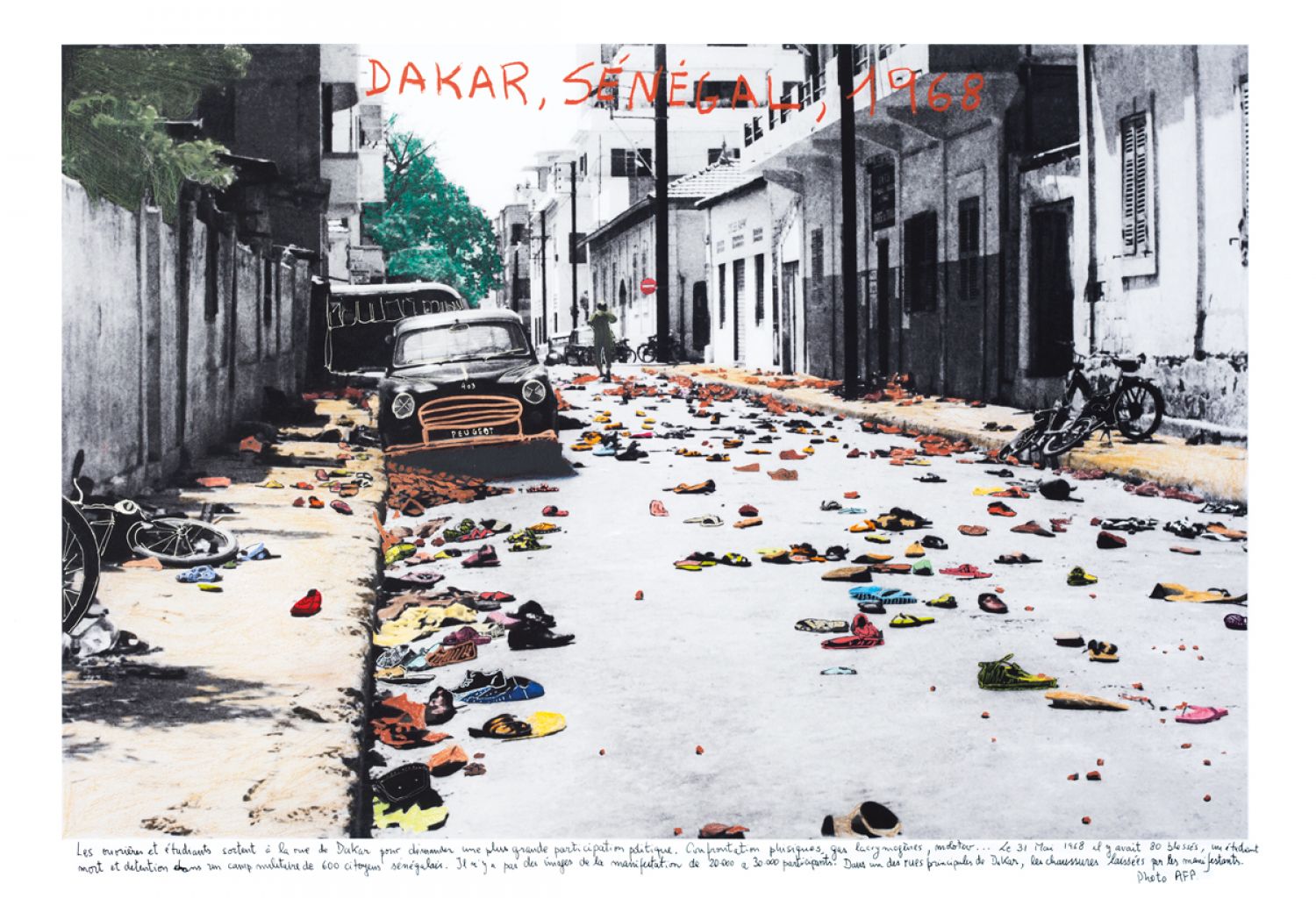

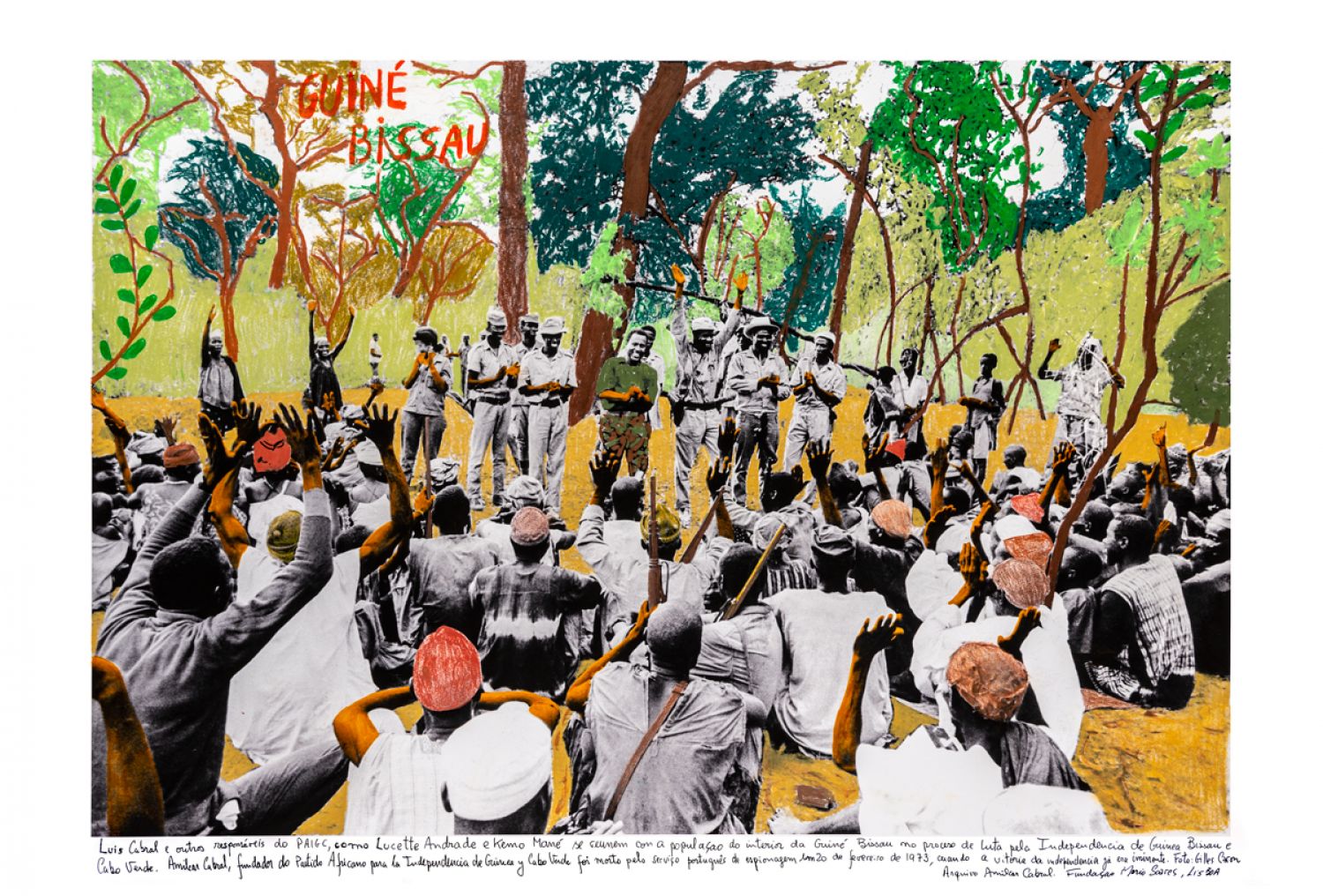

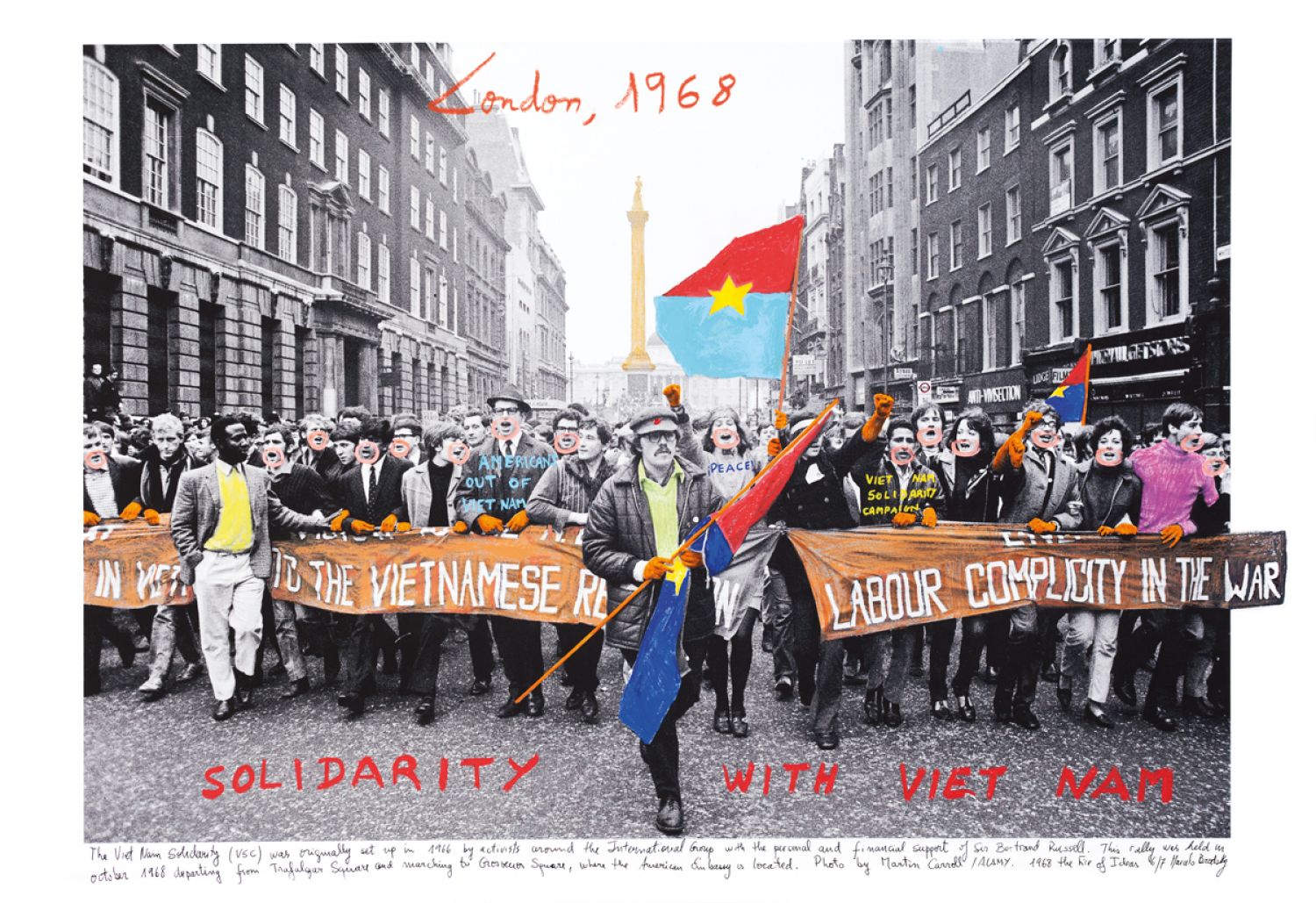

Brodsky, who has owned and directed a photographic agency for many years in Spain and Latin America, does not use the media merely as a source of inspiration. Rather, he turns the media itself into an artwork. Selecting photographs collected in documentary archives around the world, the artist manipulates them:[4] by adding handwritten comments and highlighting meaningful details with the help of bright and vivid colours, he stimulates a dialogue between the pre-existing narratives conveyed by the original sources and his own interpretation of those texts and images. Brodsky has been employing this strategy since 1996, when he realized Buena Memoria (Good Memory), one of his most celebrated and iconic works to date.[5] Departing from an enlarged black and white group photograph of his class taken at school in 1967, at the age of thirteen, Brodsky intervened it with annotations, drew circles, arrows and crosses to visually trace to date the destiny of the children portrayed on the image. His comments read like succinct epitaphs celebrating heroic patriots: «Claudio was killed fighting the military», «Pablo died of an incurable disease», «Martín is the first one they disappeared», «Ana went to live in Israel»…[6] This modus operandi is still at the base of the artist’s most recent projects, but over the years it has greatly gained in strength, both in style and in the variety of its contents.

Brodsky can lean on a long standing tradition in Argentina, the inception of which dates back to the second half of the 1960s, when media theory based on the work of Marshal McLuhan, Umberto Eco and Roland Barthes was taught at the Instituto Torcuato di Tella in Buenos Aires. These theories inspired several vanguard projects like the legendary Tucumán arde (Tucuman is Burning)[7] as well as an entire generation of artists slightly older than Brodsky – such as Marta Minujín, Eduardo Costa, Raúl Escar and Roberto Jacoby – to use media not just as a tool for transferring information but also as a critical «device for the exaltation and construction of alternative realities»[8]. Brodsky’s work is an ongoing reflection on the way in which media affects reality (and its memory), and contributes to the shaping of national cultural identity through the diffusion of heavy edited self-portraits of the society it depicts. But his work is also an investigation of how media can be transformed into an instrument capable of creating awareness of such patterns, while instigating discussion among present and future generations. As he explains: «Photography’s potential to record imperceptible changes and the passage of time in each person’s face might be extended exponentially to register human experience, artistic events and performative actions that draw a sort of map of collective action, creating a socio-political itinerary of gestures, dramatizations, positions and provocations. It would be a kind of social aura, a collective imaginary.»[9]

The Poetics of Resistance reunites two major groups of works created by the artist between 2014 and 2019: 1968. The Fire of Ideas, composed of 55 intervened archival photographs devoted to the international mobilisations and protests of workers and students in 1968, and the series of 20 images centred on the decolonisation process in Africa and its progressive transition to independence during the second half of the 20th century. The project also encompasses two further and still ongoing lines of inquiry by Brodsky, devoted to the anti-Franco resistance in Spain and to today’s burning question of migrants and refugees―in which, for the very first time, the artist engages in a reflection on contemporary issues. Adding annotations and clearly non-impartial captions, Brodsky recounts historic episodes of major turmoil and revolution: from the anti-Vietnam War protests in London to the struggle for the independence of Congo and the rebellions caused by the murder of his anti-colonialist Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba in 1961; from the 1968-revolts of the student unions in Dakar requesting more political freedom from President Léopold Senghor to the violent state of emergency in South Africa during the anti-Apartheid struggle in the 1980s. Departing from black and white photographs documenting social and political events around the globe, Brodsky’s plastic and textual artistic interventions aim at engaging the viewer, regardless of where he or she lives and whatever his or her background is, not just in a conceptual and aloof reflection on those historical moments and histories of resistance, but in a responsive and personal identification with their protagonists. What is the relation between the bloody repression of the student protests in 1968 pre-Olympic Mexico and the disappearance of 43 students in Ayotzinapa on September 26, 2014? Is there a connection between the current migrants’ crisis in Europe and Africa’s colonial past? These and similar questions are raised by Brodsky’s works and addressed to the viewer.

Brodsky is particularly committed to speaking to younger generations. He knows very well that, in the time of social media and instant communication, this can happen effectively mainly through images and short messages. «Professionals of the image like me», he points out, have the «responsibility» to positively shape the way we make use of them in our society.[10]

As a human rights activist―he is one of the co-founders of the Parque de la memoria in Buenos Aires[11] ―Brodsky believes that his artistic practice can help to effect positive change by promoting awareness in people, worldwide. His work is an empowering manifestation of that strange and absurd, but nonetheless strident hope referred to by Peter Weiss, that is the common denominator of past and present human action and desire, and which prompts the urge to act and to bring about change that is at the hearth of every gesture of resistance. Participating in the «global discourse about historical trauma»[12] , Brodsky’s intervened photographs are «memory art»[13] with a strong impact on our present and future: intensely visualizing past traumas, they counteract the fatalism that too often inhibits us from resisting, taking action and contributing to revolutions big and small which take place daily, around the world.

–

Curated by Katherine Sirois

Footnotes

- ^ Peter Weiss in conversation with Heinz Ludwig Arnold (September 19, 1981). In: Alexander Stephan (ed.), Die Ästhetik des Widerstands. (Frankfurt/Main, 1983), p. 48. Translation by the author. Part of the recording of the interview is accessible online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X_D0zqMaBjU

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Human rights organizations maintain that the Argentinian military dictatorship is responsible for the abduction, torture and death or disappearance of approximately 30,000 people. See Emilio Crenzel, «Toward a History of the Memory of Political Violence and the Disappeared in Argentina». In: Eugenia Allier-Montaño and Emilio Crenzel (eds), The Struggle for Memory in Latin America. Recent History and Political Violence. (New York, 2005), pp. 15–33, here p. 16.

- ^ Before reworking them, Brodsky licences all the images with the owning agency or photographer.

- ^ Buena memoria. Un ensayo fotográfico de Marcelo Brodsky con textos de Martín Caparrós, José Pablo Feinmann, Juan Gelman / Good Memory. A Photographic Essay by Marcelo Brodsky with Texts by Martín Caparrós, José Pablo Feinmann, Juan Gelman (first edition in Spanish and English, Lamarca, Buenos Aires, 1997. Reedited in German and English, Haatje Cantz, Ostfildern, 2005).

- ^ «A Claudio lo mataron en un enfrentamiento», «Pablo murió de una enfermedad incurable», «Martín fue el primero que se llevaron», «Ana se fue a vivir a Israel». Translation by the author.

- ^ The project took place in Rosario, Argentina, in 1968 as an experiment of grassroots information with the objective of challenging the official discourse and denouncing the dramatic effects of the military government of Juan Carlos Onganía on the economy of the region. For an in-depth account sees the analysis by Luis Camnitzer, «Tucumán arde. Politics in Art». In: Camnitzer, Conceptualism in Latin American Art: Didactics of Liberation. (Austin, Texas, 2007), pp. 60–72.

- ^ See Rodrigo Alonso, «Strategies to ‘Realize’ Reality», in Heike Munder (ed.), Resistance Performed. An Anthology on Aesthetic Strategies under Repressive Regimes in Latin America. Exh. cat., Migros Museum für Gegenwartskunst, Zurich. (Zurich, 2015), pp. 38–45, here p. 41.

- ^ Marcelo Brodsky, «Políticas del cuerpo en América Latina». In: Brodsky and Julio Pantoja (eds), Body Politics. Políticas del cuerpo en la fotografía latinoamericana. (Buenos Aires, 2009), pp. 13–14, here p. 13.

- ^ Brodsky during a Skype conversation with the author, December 20, 2018.

- ^ The Parque de la memoria (Memory Park) is a public monument and art exhibition space inaugurated in 2007 on the banks of the Plata River in remembrance and honour of the victims of Argentina´s military dictatorship.

- ^ Andres Huyssen, «El arte mnemónico de Marcelo Brodsky / The Mnemonic Art of Marcelo Brodsky». In: Nexo. Un ensayo fotográfico de / A photographic Essay by Marcelo Brodsky». (Buenos Aires, 2001), pp. 7–11, here p. 8.

- ^ Ibid., p. 9.