Horamen

Adrián Balseca

VALUES

Manuela Moscoso, Manuela Ribadeneira and Pablo Lafuente

Value. Use. Function. Legacy. Resources. Symbol. Price. Purpose. Funds. Wealth. Patrimony. Exploitation. Value.

After centuries in which they were accompanied by silence, the most recent decades in the life of a great number of pre-Colombian pieces are full of words – words that refer to a semantic field but that also open the doors to a myriad of divergent and, sometimes, opposing perspectives. For example, what the pieces were for those who made them (about whom we know some things but not enough to speak with certainty) is an exercise in speculation. Scientific, but science is also, in part, speculative. What happened with them after the disappearance of those who made them, for purposes we can only imagine, is also the subject of speculation: buried, transferred, dislocated, destroyed, found, unearthed, sold, bought, rescued, desappropriated, recomposed, studied, venerated, exhibited, celebrated, observed…

Adrián Balseca’s Horamen, the third project in Zarigüeya/Alabado Contemporáneo, tells part of this history: the part that refers to those shifts in value in recent times, the moment when something is no longer appreciated as a material and is instead valued as a materialization – that is, because of its specific form. A shift that can be understood as a move away from an interest focused on ‘substance’ to another concentrated on ‘accidents’. Without implying here that accidents are less essential than substance, rather assuming that both matter and accidents are always present, but that some of them, in a specific materialization, are privileged depending on the perspective of the moment and place.

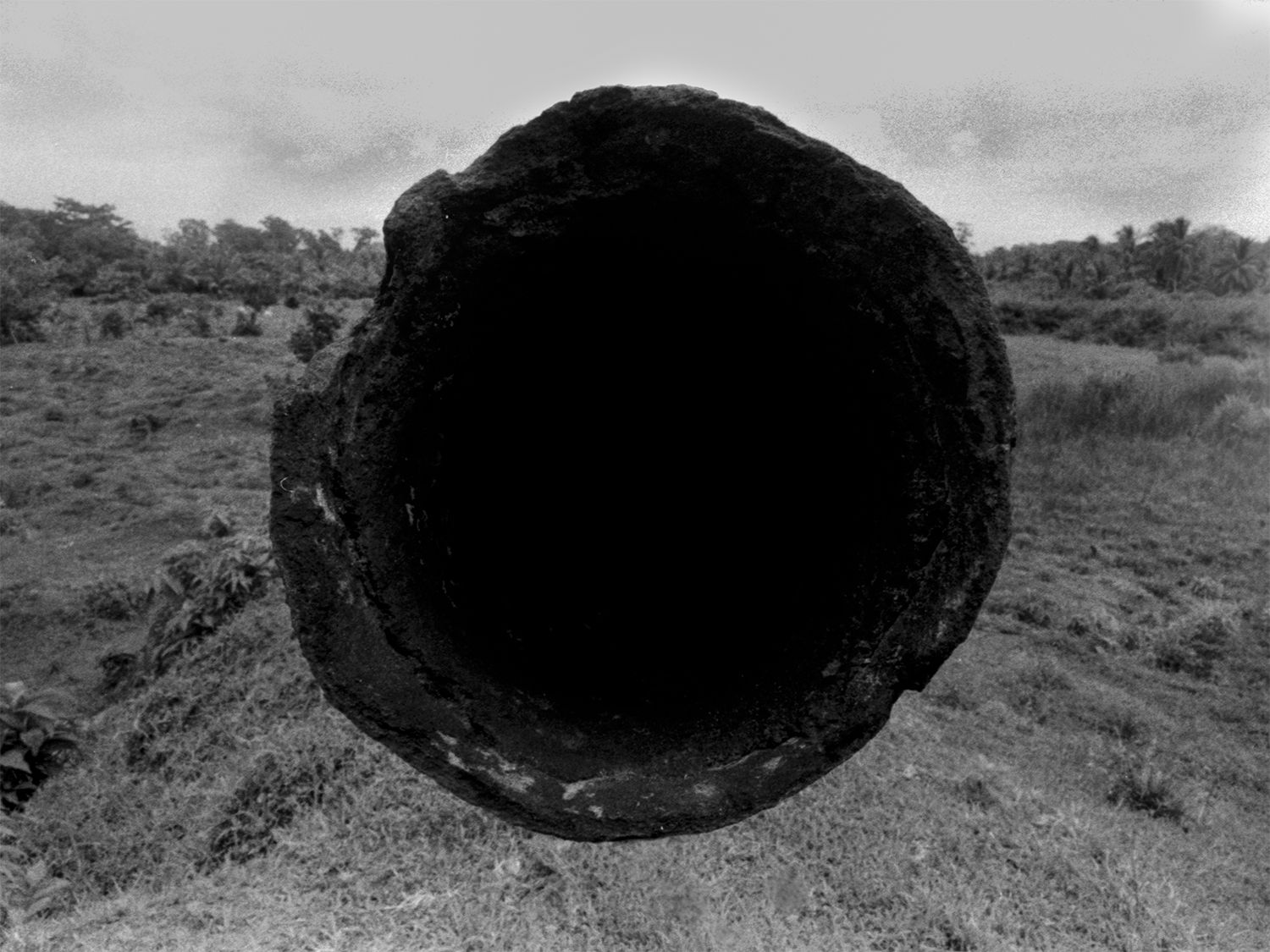

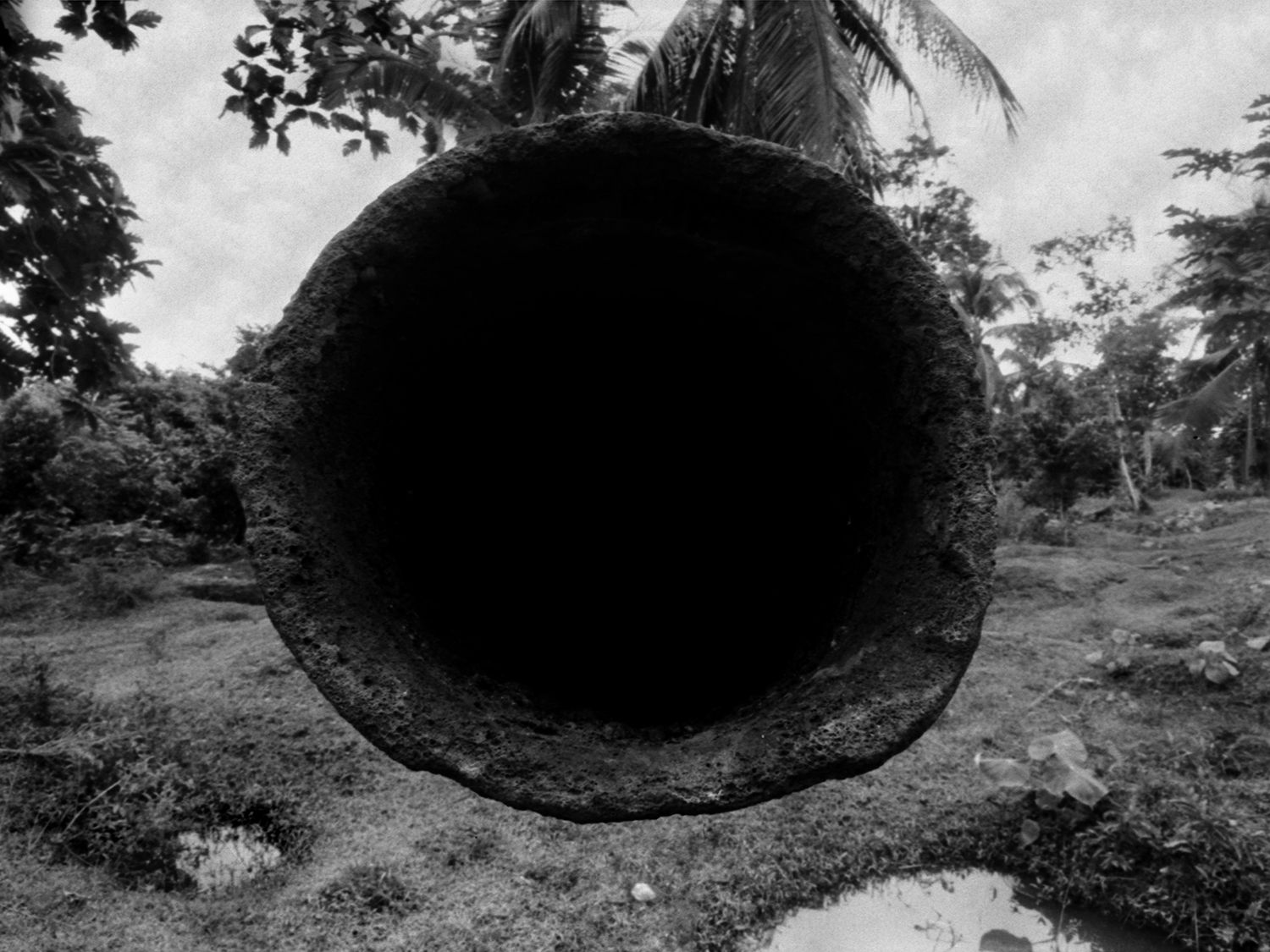

Horamen takes as its central element a transformation tool: crucibles, receptacles made of clay and graphite, and therefore resistant to high temperatures and the chemical action of hot metal, present in ancestral cultures in the Ecuadorian territory for thousands of years. Crucibles in which a substance changes form (gaining and losing accidents), in order to circulate in new contexts. Crucibles that Balseca uses as parts within a new articulation, transforming them into constellations connected by pieces of metal that denote a double cartography. Metal as a matter in transformation, without apparent agency, and at the same time as a matter that articulates, gives meaning, conducts.

Double cartography, first geographic: of the territory of the La Tolita or Tumaco culture, on the coast that goes from Esmeralda in Ecuador to Tumaco in Colombia, between 600 B.C. and 400 A.C., a culture renown for the excellence of its ceramics and goldsmiths work. La Tolita received this name because of the tolas, mounds on which those who were part of that culture lived and used as open spaces for religious practices, and as burial sites. In the words of Fray Juan de Santa Gertrudis, in the 18th century: «They call this village La Tola, because it is full of tolas, or earth mounds, and this is what I have seen, as I will tell. These tolas are burial sites for ancient indians, and as they were buried with all they had, in some of them many riches have been found.»[1]

Cartography that is also political and economic: that of extractivism, which begun almost three centuries before the writing of Fray Juan de Santa Gertrudis with the arrival of the Spanish crown, and which continues today in forms that are sometimes different, and that sometimes seem to have not changed. The understanding of what the earth offers (and, by extension, those who inhabit it) as a resource that is available for exploitation, by those who secure for themselves a situation of power. Earth is transformed into what can be obtained from it – agriculture, raw or precious materials, abundant or scarce – in the same way that bodies become production tools. Silver in Potosí, rubber in Acre, gold in, among other places, La Tolita, all of them swallowed by a black hole (a sun in reverse) in which even the landscape disappears.

Gold is the most malleable and ductile metal, which allows for the production of extremely thin sheets. It is also the heaviest, with a density of between 15.6 and 18.3 grams per cubic centimetre. It is soft, it melts at 1.063 degrees centigrade, is also an excellent conductor of heat and electricity and, perhaps more importantly, it is incorruptible: it doesn’t react to acids or oxygen, and doesn’t rust or lose its shine.

Such characteristics are ‘accidents’ that the logic of the resource privileges. A logic in which mining is compatible with the more primitive (or more imperfectly productive) method of the garimpeiros. But also, and perhaps surprisingly from the perspective of the current system of values, with the huáqueros: there was a time when the pieces made with precious metals that were found in ‘informal’ excavations were worth more as substance (as material) than as pieces with accidents that allowed for ritual, political, symbolic, communication and connection uses. This way, the crucible, through which they had passed in an initial transformation process, inflicted a new transformation in which they lost their specific materialization to become, simply, gold, silver, platinum – circulating anew to sustain and reinforce the logic of colonial exploitation. No longer a specific object, singular, immerse in the local cultural logic, but an abstract materialization, an instrument that guaranteed the circulation of capital at a global scale.

But the process of transformation doesn’t stop there. Potosí’s silver made possible not only the financing of the colonial occupation by the Spanish crown, but also its territorial wars in Europe. It also allowed, as symbolic object, a spiritual colonization: the imposition of a religion, a culture, a system of alien values, often incompatible with the preexisting ones. The image of catholic veneration, materialized in ‘precious’ metals, colonized spirits at the same time that the administrative and military apparatuses, financed by the same metals, colonized bodies.

When the Golden Sun of La Tolita became the logo of the Banco Central of Ecuador in 1976, it experienced a similar process, in which its character as image and symbol – not only as gold, as exchange tool, but also as part of an original culture – is privileged. The precious metal, the wealth it denotes, is now accompanied by another wealth: a cultural and political legacy that goes beyond colonial history, and that is the basis of a process of nation building. And thus the Golden Sun is printed on the Sucres, until these are substituted by the dollar.

But the return of an ancestral object, even if it is to its place of origin, is full of difficulties, of risks. The return of the Golden Sun, a golden sheet of 284.4 grams and 21 carats, is a path ridden with conflict. Commercial conflict, acquired by the Banco from the Swiss dealer and collector Max Konanz in 1960, who himself bought it in 1940. Scientific (speculative) conflict, reclaimed as a work from the Cañari culture on the basis of the information provided by the original sellers, information that are contested by the laboratory analyses that identify it as Tolita – the official version of the Banco Central.

No longer in danger of losing the materiality that it acquired approximately 2.000 years ago, the Golden Sun is a national symbol, an object of veneration, exposed in a glass box to be looked at. Art, legacy, patrimony, with a value no longer quantifiable, unaffected now by exchange processes. And also a symbol of pre-Colombian pieces as a whole: protected by patrimony laws, on view in museums or in private collections, displaying a splendor that sometimes is just formal, and responding to new uses, without prospects of future circulations and accompanied by words that propose stories but that always, necessarily, forget about other possible narratives.

–

«VALUES», courtesy of Casa del Alabado Museum of Pre-Columbian Art & Zarigüeya/Alabado Contemporáneo. www.zarigueyaenelalabado.org

Footnotes

- ^ Fray Juan de Santa Gertrudis, Maravillas de la naturaleza, 1771–99. Available at http://www.banrepcultural.org/blaavirtual/faunayflora/maravol1/mara27c.htm#tolas