Analogical materialism. Spiral Jetty

Susana Mouzinho

The earth's surface and the figments of the mind have a way of disintegrating into discrete regions of art.

And the movie editor, bending over such a chaos of ‘takes’ resembles a paleontologist sorting out glimpses of a world not yet together, a land that has yet to come to completion, a span of time unfinished, a spaceless limbo on some spiral reels.

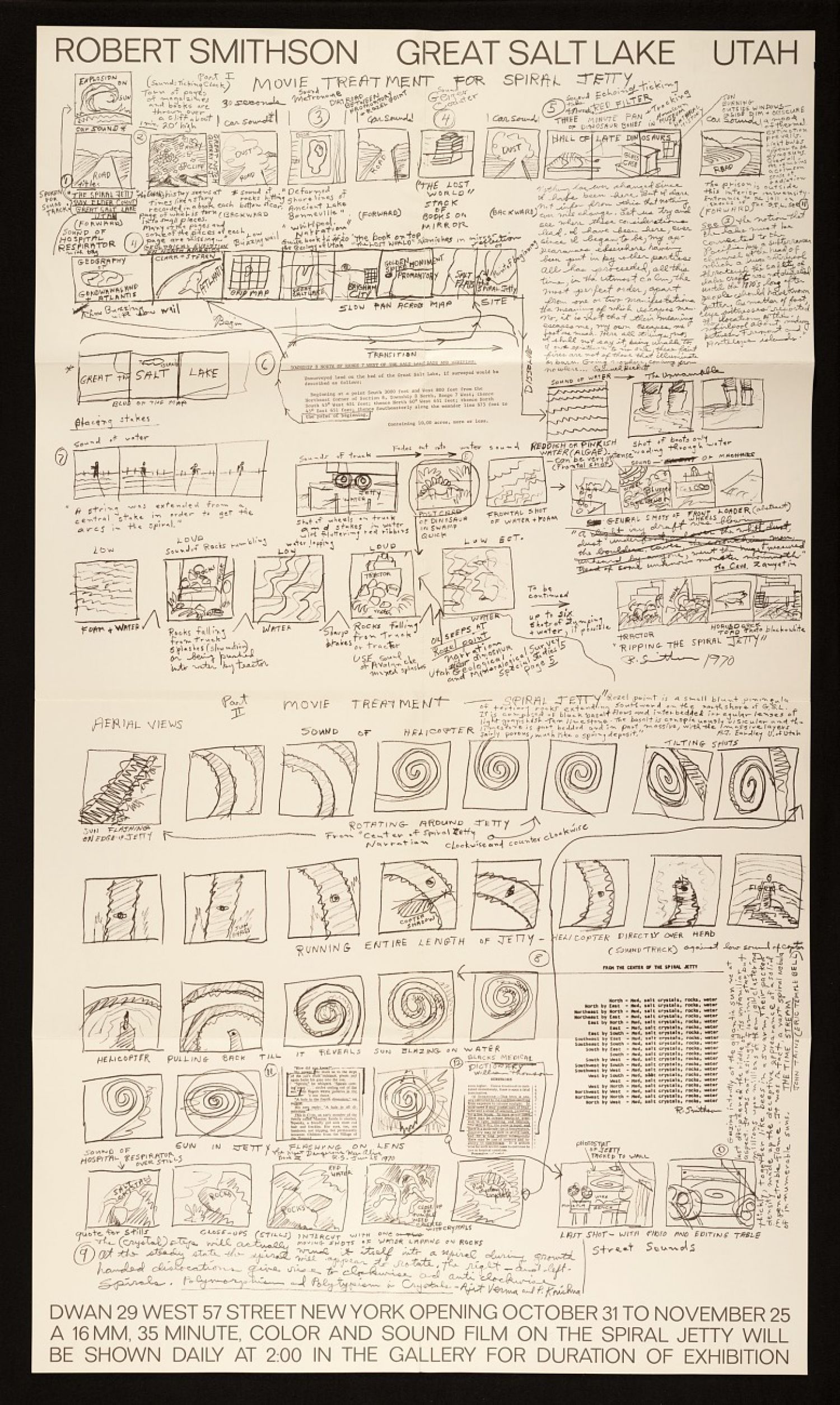

The above quotes are from Robert Smithson and underline the artists’ thinking on cinema and the construction of the film Spiral Jetty (1970), a film of the artwork (made of salt, rocks and mud) by the same name, which Smithson created in the Great Salt Lake in Utah. The Spiral Jetty project, was a complex that comprised the creation of the earthwork – a jetty – the homonymous film, the text that Smithson wrote around the experience of Spiral Jetty's production and filming, and the creation of an underground cinema that would be located in a bellow ground cave and would project only the film of its own construction. Although these are independent artistic objects, we can, however, think of the abovementioned film as more than a mere documentation of the process of the jetty’s construction. The film is, I propose, an expanded cinematographic work that articulates Smithson's concerns regarding art and the great narrative of matter that cinema allowed him to create. For cinema seems to be, for Smithson, a technique (a poiesis) based on a set of operations that use devices - the eye of the camera is a favorite figure of Smithson - that allow for the ordering of the scattered fragments of destruction that nature has become.

Robert Smithson was a prolific writer and his texts allow us to locate certain concepts and themes that clarify his relation with what he considered the cinematic state of the real – decomposable and captured by the camera – and whose creative potential could be managed through editing, montage. Creative potential, here, is synonymous with the demonstration of the temporalities that coexist in matter and its transformation in its translation into moving images.[1]

In Smithson, cinema is a construction, a survey of the obscurities of matter, a technical procedure that gives back in another cinematic form, the cinematic that the artist finds on the surface of reality. He writes in A Tour of the Monuments of Passaic, New Jersey (1967): «Noon-day sunshine cinema-ized the site, turning the bridge and the river into an over-exposed picture. Photographing it with my Instamatic 400 was like photographing a photograph. The sun became a monstrous light-bulb that projected a detached series of ‘stills’ through my Instamatic into my eye.»[2]

Frequent cinemagoer, Smithson's relationship with moving images seems to be, on the one hand, based on a productive conception of cinema, in the sense that the camera was considered a technique for the artist and, on the other hand, in the cinematic possibilities of articulation and reflection of the various temporalities which Smithson saw existing in the world and the mutability of matter. But, in the context of an extended experimentation with the moving image, that enters the gallery space and the movement that sculpture makes out of the pedestal, how to classify this expanded cinema? What interested Smithson was the cut, the montage, the reordering of shots and movements, in order to deconstruct space and affix time to strata. In Smithson, cinema was not what he called rationalism, that is, naturalism, but rather a relationship with matter (material), which is the diegesis of the film, a geological space that he considered as having a transitive relation with cinema and which, because the archaeological markers of the jetty film are the past and the future, brings to the screen an «any space whatever.»

It is not a question, then, of thinking about the aggregative character of the cinematographic device, but of thinking about temporalities and the inscription that the material can make in a film and vice versa. This may be an imaginative leap, but one that seems pertinent. In Smithson's cinematographic practice there’s a transposition of the Site, Non-Site (place, non-place) dialectic. Generally speaking, the Site is the place from which something is subtracted that is then placed on the Non-Site, thus responding to an addition principle. The Non-Site contains the Site and refers to it and vice versa, (the big becomes small, the small becomes big. This question of scale was, in fact, something that fascinated Smithson in relation to cinema - in cinema «everything it is out of proportion», he said). The film Spiral Jetty acts as an equivalent to the sculpture and the sculpture works as an equivalent of the film. The metaphors used by Smithson are captivating in this sense, the approach to a place, to a landscape as a cinematic space made of light and sound, capable of being cut out by the camera and reorganized, realigned by the montage.

Art historian George Baker[3] sees in the «place/non-place» dialectic the development of a «cinema model» that derives from Smithson's interest in cinema’s representation strategies. The dialectic of Site - Non-Site and the decomposition and recomposition of frames of the film Spiral Jetty in the pages of Artforum magazine are synonymous with a model of cinema from which art can be thought. It is the exploration of the «relational potential» of cinema that Baker sees updated in the film Spiral Jetty, which makes cinema the epitome of a «logic of vectorization,» that makes up a plane of immanence from which the association of images makes use of logic of the interstice, of this cut that does not obey a logic of continuity, is not synonymous with an indivisible space and linear time, but with an expansion of the invisible in matter to a logic of time and movement that can only be revealed by cinema.

The film’s diegesis takes us on a journey and shows us the construction of the jetty as a geological image of the land that Smithson brought to the immanence of the world. To arrive at the jetty site through the film is to go back in time, it is to make a mnemonic trip. Smithson's film is the antithesis of the perfect crystal, underlining therefore, «a decentered, fundamentally entropic temporality that seems to insist that time cannot be considered a function of the subject but is rather the subject that comes to be always and only through its temporalization.»[4] A Deleuzian stratigraphic image that Smithson complicates, since he sees inscribed in the temporality of images and things, the signs of the future while working on an iconography and an imaginary that refers to the past, with reference to dinosaurs, caves, etc. In the ruined landscape of New Jersey, looking at the rubble of abandoned construction works, Smithson stresses that the ruins are the sign of the potential to be realized, they are ruins in reverse, nothing was created from there.

To think of the Spiral Jetty film from concepts of cinematic temporality and historical time is a captivating reading. For Smithson, cinema is an «Archeozoic medium,» which should be understood as more than a simple translation of Smithson's interest in matter and the times of the earth, but rather as underlining a condition of the analog in cinema: the film and the work are transitive, present, past and future are concomitant. Smithson's approach is not teleological, there is a tension that prevents the work from being closed. The cinema, made up of different stages and pieces of equipment that are added to compose a film, thus being at risk of transformation, has these same non-synchronous temporalities.

The declination of the work Spiral Jetty in a film authorizes a spatio-temporal relationship of the work in a different way. The scale of shots and the play of temporalities that assist the construction and experience of the work, are effectively transformed by a diegesis that inscribes in the film a geological temporality and a space made up of paths and accumulations, giving the film an expansive timelessness. By this I mean that, in Smithson's cinematic landscapes, abstractions of matter are cut out (we see details of salt, water), we go from details to expansion (the jetty shot from a helicopter), and through the alternation between the large and small scale shots, Smithson translates the temporality and transformation of matter in a cinematic form. In addition to cutting the shots, Smithson rehearses camera movements that reproduce the shape of the work and that could be interpreted as a kind of McLhuanism – an embodiment of the work in the device.[5] Productively for me, it will be to understand that what Smithson sees as the cinematic of the real, in his approach to McLuhan, is that after the Second World War, with the launch of the bombs in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, naturalism is no longer possible, that the Real has become a series of fixed, gaseous images that need to be restored - McLuhan's reel time. The cinematographic image can give us time coordinates and the progression of things in space and thus demonstrate how to transform a given space into any space whatever, which is the potential of the spiral jetty, an entropic space that is being built, that takes us out of it and nowhere.[6]

We can thus conclude the construction of Smithson’s expanded any space whatever, a Deleuzian concept that implies the construction of an undetermined space that destabilizes the position of the human in the world and the modalities of her perception. For Smithson, scale and our positioning depend on our attention to the «actualities of perception. » A cinematic state of the real leads Smithson to consider that matter is a vibration that, when perceived, becomes a physiological reaction, a spasm, a torpor. The shots of the sun, of its incandescence, seem to be the cinematographic translations of this idea. A stain of light which disorients, which induces torpor and loss of bearings. This perception, or awareness of a world that has become a series of fixed shots, seems to bring Smithson closer to the postulate of Deleuze's world made image. But perception here is not anthropomorphic, subjective: to perceive matter is to see what it hides, to see the strata, potentiality. Eric Alliez[7] mentions that in Deleuze, consciousness is no longer the consciousness of a thing, rather, there is the affirmation of a plane of immanence where becoming transforms cinema into a meta-cinema, the universe becomes cinema itself: «Deleuze explains that because cinema suppresses the anchoring of the subject in the horizon of the world, it allows us to ‘go back up towards the accentred state of things,’ toward a state of pure molecular vibrations, which now require transformation, and not translation.» The production of any space whatever, – espace quelconque – signals the production of a decomposable space, whose axes vary and which signals not only the mobility of the camera, the technique, as the production of a non-teleological perception of time, that precedes and projects the historical dimension of the events represented on the screen. The variations in scale, the decomposable space, from the start already cinematic, the affectation of the senses due to the vibrations of matter that cinema can translate, the cut that causes spatial indeterminacy, that rejects coordinates and that sets in motion what is under the surface of the matter thus creating temporal stratigraphy, place Smithson at this point of transition, in the production of an expanded any space whatever. The place of entropy, a central figure of the artist's thought, keeps matter in a state of indeterminacy, ancient and proleptic, which cinema translates as an infinite potential for the transformation of matter.

Footnotes

- ^ Quotes Michael Snow’s Wavelenght (1967) at the end of Spiral Jetty, by zooming in on a photograph of the jetty. Smithson compared this image of a «endless sea» to the «infinite flow of the film camera».

- ^ Robert Smithson, «A Tour of the Monuments of Passaic, New Jersey» in Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings, ed. Jack Flam. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 1996, 70.

- ^ «The Cinema Model» in Lynne Cooke e Kelly, Karen, ed. Robert Smithson: Spiral Jetty. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 2005, 78 - 113.

- ^ Andrew Uroskie, «La Jetée en Spirale: Robert Smithson’s Stratigraphic Cinema», Grey Room 19 (Spring 2005): 74.

- ^ Cf. Stefan Heienreich, «Museum, Media, Society», Robert Smithson, Art in Continual Movement.

- ^ Smithson distances himself from McLuhan’s anthropomorphism; Smithson says that technological manifestations are «less extensions» of man than aggregates of elements.

- ^ Eric Alliez, «Midday, Midnight. The emergence of Cine-Thinking» in The Brain is the Screen: Deleuze and the Philosophy of Cinema, ed. Gregory Flaxman. Minneapolis, London: University of Minnesota Press, 2000, 294.