work photographs. and other drawings

Carlos Nogueira & Paula Parente Pinto

Carlos Nogueira: The image of sculpture and the matter of images

«Nature is a temple whose living colonnades

Breathe forth a mystic speech in fitful sighs;

Man wanders among the symbols in those glades

Where all things watch him with familiar eyes.

Like dwindling echoes gathered far away

Into a deep and thronging unison

Huge as the night or as the light of day,

All scents and sounds and colors meet as one.»[1]

work photographs. and other drawings is Carlos Nogueira’s first photographic exposition. After several occasional participations in other exhibitions, this is the first time that photography features as the exposition’s central element. But if on one hand such a centrality does not turn it into a simple photography exhibition, on the other hand many of the images shown here are not unknown; what photography reveals in the present exposition is a new landscape of correspondences between process and product, between object and image, between production and reproduction, in Carlos Nogueira’s work.

In some cases these correspondences are, quite literally, posted items, mail, communication, such as in the series paisagem(s) de (man)dar [landscape(s) to be sent/given away] (1980),[2] created through postcard collages. These landscape(s) to be sent/given away testify to the scope of a work field that refuses any linear relationship between process and product, as well as the reduction of the artwork to its final image. In Nogueira’s photography the objects are not transparent, nor are the images an outcome. His pieces encompass an infinite number of images that spread out into nature, and these images lead us further towards other objects. Made from found images, these landscape(s) to be sent/given away offer a key to read the fruitful interconnections between sculpture and photography in Carlos Nogueira’s work. How do these several copies of the same postcards with images of water, land and air, mounted according to a repetitive sequence, deconstruct the perception of photography as a mechanical recording medium, technically reproducible? Carlos Nogueira takes a multiple image, serially produced and with a predetermined format, subjects it to a linear and repetitive process of montage, and creates other postcards, still showing the same landscape, but now also the artist’s work and personal perspective. Landscape is presented as a transformed object. And, contrarily to what one might expect, it is by incorporating a reproduction and repetition device that these images become unique. In other words, a technically reproduced object is turned into an original, even though the recombined image does not alter in the least the postcard’s standard format: a common and industrialized object that may be sent to anyone, but whose specific existence is asserted as soon as it communicates something individually and singularly; the postcard’s individualized communication depends therefore on the existence of a recipient. Carlos Nogueira’s conceptual gesture recombines images, objects and concepts of an apparently transparent and consensual nature, incorporating them into the process and into his singular artistic path. What is given is not the image itself, but rather the appropriation and recombination implied in such an act, which marks a relationship with an individual recipient. Sent out, included in an art exhibition or metamorphosed into other objects, Carlos Nogueira’s artworks entail an exercise of displacement. They evoke the irreproducibility of the gesture, establishing at the same time a network of affinities. The image-landscape is transformed into a communicating object.

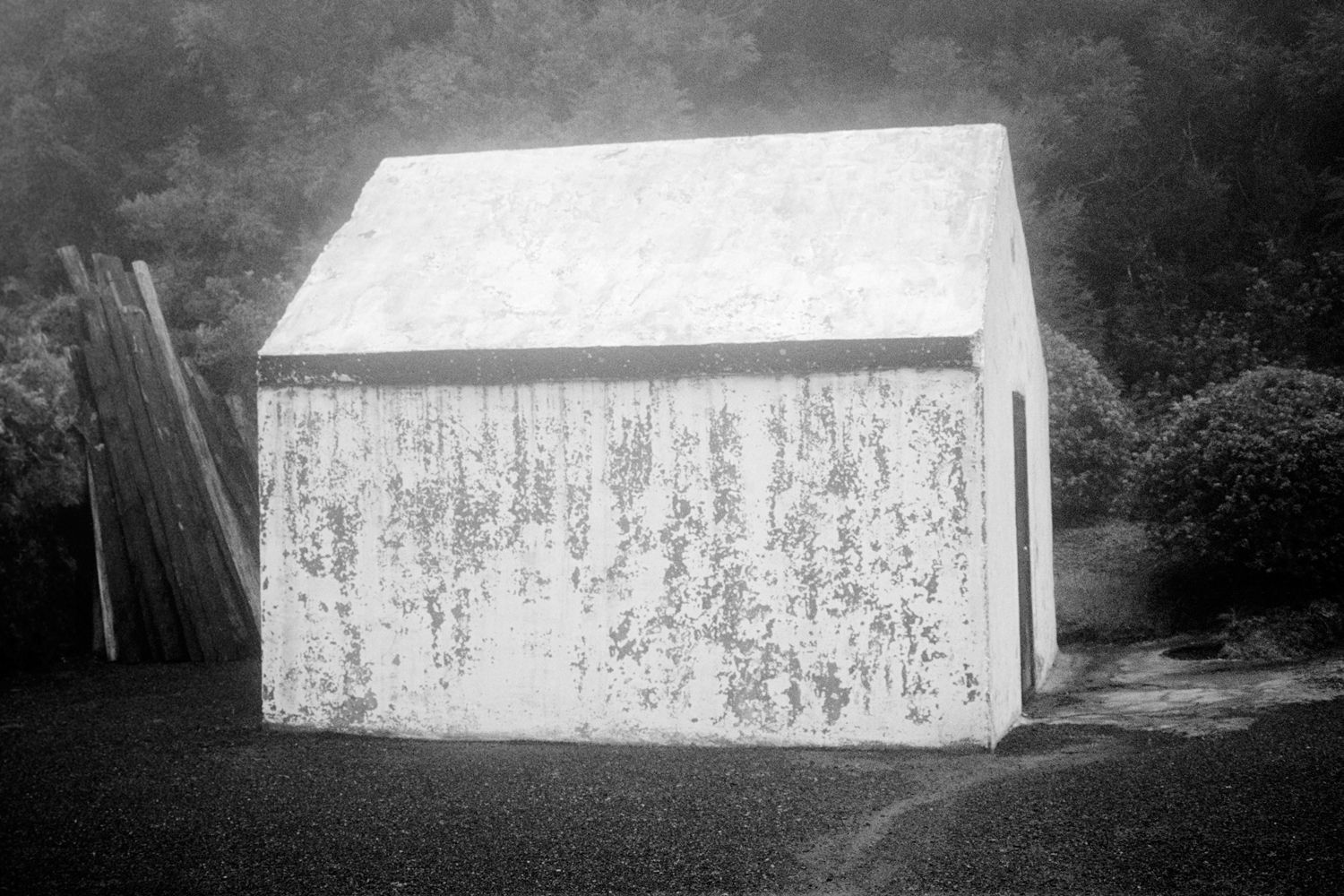

Carlos Nogueira’s photography collection includes assorted pictures of recombined and multi-temporal objects, casually found by the artist, and photographic documents that refer to his artworks but do not replace them as final images. Pictures of landscapes anonymously humanized and of surviving objects/ruins, alongside images that are directly related to an individual authorship, at a precise time and place. The photographic reproductions of art pieces are unequivocal as to their identification and existence – their primary function is to document Carlos Nogueira’s work –, but it is the paradoxical nature of the work in these photographs that prompts us to reflect on the liberating double-sense in the title work photographs. Photographs are taken in transit and their value is equally transient. Carlos Nogueira does not move the objects shown in his photographs into the exposition space (he doesn’t work with ready-mades), nor does he transform the photographic reproductions of his artworks into a pictorial (contemplative) field. These photographs are displayed as an integral component of his work process, without beginning or end in the art piece. A photograph does not replace the object it refers to, nor is it just its direct referent.

In 1859 Charles Baudelaire criticized the understanding of photography as an art form, for his notion of realism didn’t correspond to the image of a physical mirror, but rather to a mental reflection pertaining to the domain of imagination.[3] Carlos Nogueira also searches for this peculiar correspondence – to use Baudelaire’s almost kinesthetic expression – between object and experience, without reducing it to a photographic image seen as an automatic mirror of the physical world. Carlos Nogueira’s photographs propel the imagination and challenge the visible.

At the same time, his work photographs. and other drawings are a documental record and a sensorial field, functioning as a key to read objects that are not literally referred to, but also as a device for the accumulation of experiences and meanings. Some of the photographs reveal a collector of images who pays close attention to the changes in the landscape, and other ones a transformative agent. The former do not disclose themselves without the latter, and vice-versa. This false reflection between object and image is implied in the exposition’s title, by the impossibility of defining its own field. It is a game of mirrors which manifests itself in the complex interconnection between the new photographic prints and the way the exhibition is set up: a three-dimensional construction designed by Carlos Nogueira, which at first seems to be a sculptural object and then reveals itself as the photographs’ displayer. In the whole, such a device creates an object-vehicle, conferring a body to images that persistently refuse to present themselves as «proper work».

The title also refers to the link between photography and drawing, an important element in Carlos Nogueira’s work. Standing somewhere between project sketch and representation, the significance of his drawings is similarly impossible to fully determine. Image, object and idea are expressed in overlapping layers and hardly ever presented in a stable and recognizable way. The intentions of these pieces’ complex matter are revealed in titles such as «drawings», applied by the artist to a number of small three-dimensional objects recovered after being disposed of (former die-cuts which already conferred volume to the cardboard’s two-dimensional surface and turned cutouts into containers). The photographs, too, testify to this apparent functional discrepancy through which everyday life becomes undifferentiated, in the clear purpose of rescuing from invisibility the multi-temporality which the contemporary world allows it to take. Carlos Nogueira seeks out, displaces, recovers, transfers and transforms the material condition of objects, in a process that involves space, time and memory, in order to retrieve the experiences they encompass. His objects represent a poetic materialization. Beyond the refined materiality of their components and their technically precise execution, these artworks lead first and foremost to unlikely encounters between images and the imagination. Although photography is the only medium seemingly able to reproduce the visual perception of an object, these work photographs endeavour, paradoxically, to ascertain the disturbances that the photographic image introduces in the relationships between object, image and idea. Unlike the conceptualism of artists such as Joseph Kosuth, who sought to emphasize experience as a cognitive, visual and material consensus, Carlos Nogueira deals with the improbability, the strangeness and the singularity that effectively derive from the historiography of objects, from their spatial-temporal recombination and their interpretation: what differentiates his work is the conceivable inflection between idea and form, or between project and object.

The exposition work photographs. and other drawings further clarifies the system of significations brought about by the clash between the rationality imposed on objects and the irrationality of the needs that justify them.[4] This double determination becomes apparent when Carlos Nogueira traces the shadow that runs through objects in drawings relating to his sculptures, or when he turns inside out the walls he transfers into the art gallery space. The poetic condition of Carlos Nogueira’s work surfaces in moments like these; in these bridges that strengthen the exchanges between photography and sculpture, rather than having them reflecting one another as in a mirror.

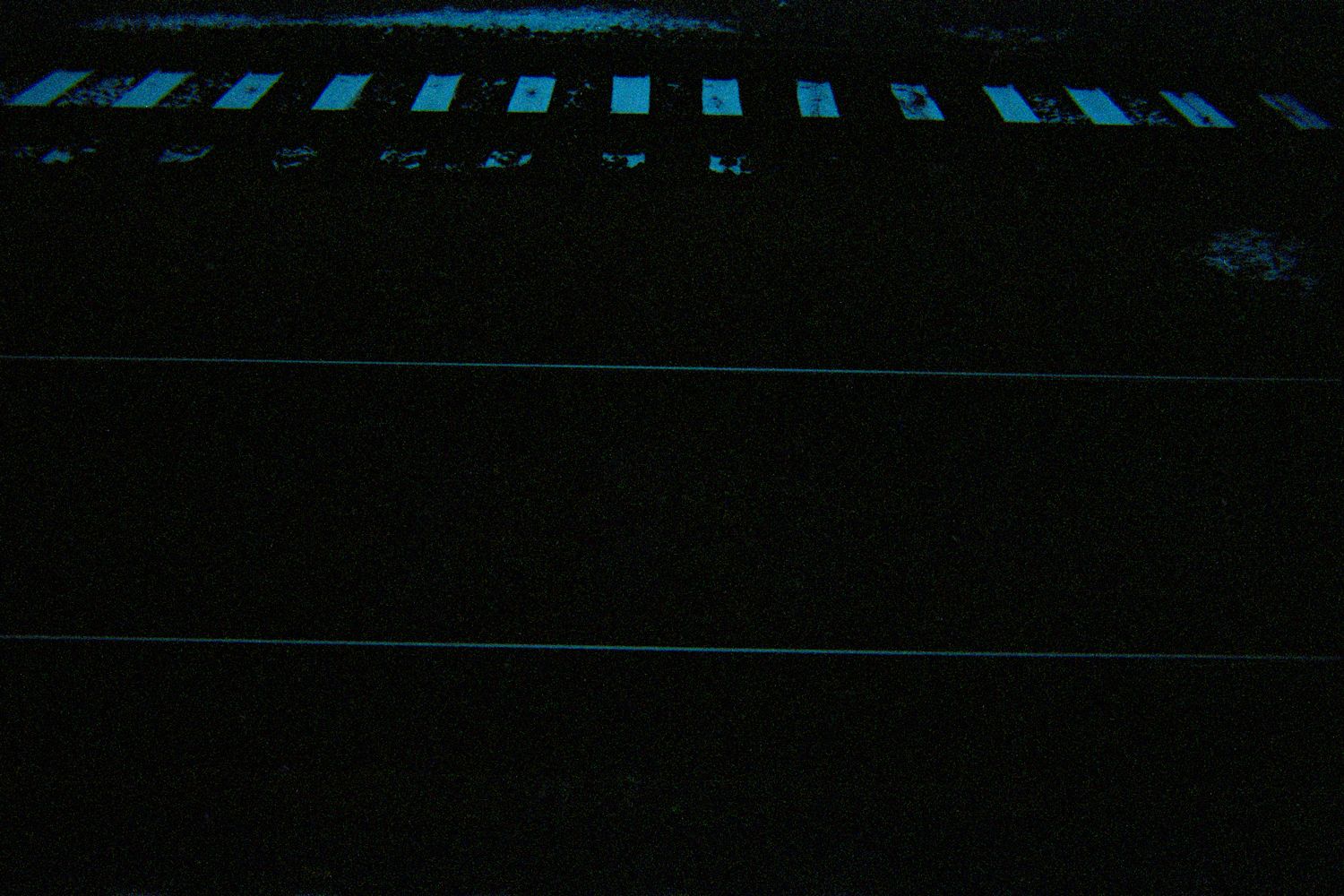

In work photographs. and other drawings Carlos Nogueira combines pictures of objects taken during his travels with photographs of the works created throughout his artistic course. While the former have no defined identity, the latter are perfectly recognizable. On one hand, the degeneration of objects which have lost their primary function, on the other, the exactness of constructions freed from the constraints of functionality. The obvious link between them is the creative process. In such a context, one must return to the preparatory sketches for the landscape(s) to be sent/given away, sheets of paper which are not white, but rather show the indetermination of any space that becomes available, where one finds rules of proportion and geometrical layouts which refer to a particular work process. We may also relate the preparatory sketches for the landscapes to be sent/given away to the placement drawings for the sculptures that Carlos Nogueira photographically documents. These preparatory sketches condition the final outcome of the work, but do not anticipate it. On the contrary, the relationship between the preparatory sketch and the final outcome or its interpretation is always a surprising and unexpected one. This contrast, issuing from a reciprocal reading or a continuous exchange between the moment before and the moment after, becomes apparent in the postcards where the jagged outline of a lawn is interrupted by the horizontal skyline. The line, which both defines the starkness of the geometrical crease and reveals the unevenness of the organic contour, is consistently featured in the photographs as well as physically present in Carlos Nogueira’s sculptures. The same line may be seen in the chiseled out profile of the hydraulic tiles in construção com chão branco a partir de dentro [construction with white floor from the inside out] (1998). In one of the photographs, Carlos Nogueira captures the gesture that breaks off the horizontal tension of a line, diverting it. This is a line that becomes a body as soon as it turns into a contact zone. Like no other medium, photography has the ability to represent the tension between the reproductive exactness of its mechanical condition and the revelation of something that won’t ever be captured again.

The deliberate transformation of found objects disassociates them from their condition conceptually defined as objective. The photographs that Carlos Nogueira has been making since the seventies reflect an affinity with the appropriation, transformation and recombination of objects and their meanings. Although common, the objects photographed by Carlos Nogueira have lost their undisputable definition, and what made their repossession so irresistible was the mechanism of strangeness they’ve been subjected to. It is this potential of objects for being recombined that narrows the distance between Carlos Nogueira’s photographic documents and his work as an artist. The same process of strangeness occurs in performances such as gosto muito de ti [I like you a lot] (1980), a street action wherein the artist makes a hundred flower bouquets and loses them deliberately along the way between Oeiras and Lisbon, making them available for countless imaginary and improbable rendezvous, which cannot be reduced to an object (the flower bouquet) or an image (the project sketch). Carlos Nogueira’s photographs do not hold a defined or definitive status, but rather suggest stories that go beyond what they can show or allow us to see.

Recently, in palavras. e outras construções com tempo [words. and other constructions with time] (Galeria Diferença, 2017), a piece consisting of a compartmented metallic cabinet, Carlos Nogueira displayed, among other objects, a stack of photographic paper boxes. Their contents were given by inscriptions on their respective sides: projects, pages, drawings, postcards, photocopies, letters, catalogues, napkins, translations, documents, photographs, and so on, organized by themes that suggested various memories and images assembled in a single artwork. This construction embodied a multiplicity of memories, evoked by the accumulation of some of his works’ titles. work photographs. and other drawings reverses this suggestive process, possibly allowing us to see the enlarged photographic prints merely referred to in the other artwork. Despite their uniform format and their structure, specifically conceived for the present context, the photographs are not singularized; they persist as a plural and cumulative process. These photographic images do not have just one valence, nor is there any distinction of value between them. They are gathered here as in a panel, where they might as well be reproductions of paintings, newspaper clippings, drawings, postcards or written pages, converted into a common language and reflecting the experiences of the one who has collected them. Used with this amplitude, in their ability to overlap different mediums and amass various experiences, the photographs challenge our expectations regarding art itself and the museum space; otherwise they might be, as a whole, a map for some possible territories.

The ever present determination to develop the functions of objects into their full range of possibilities features in one of Carlos Nogueira’s early performances: o pombal. 99 pombas de brincar para outros tantos usadores [the dovecote. 99 toy pigeons for an equal number of users] (1978). There already, serially produced objects would incorporate whatever the «users» decided to do with them. Similarly, os dias cinzentos/ lápis de pintar dias cinzentos [the grey days/ pencils for colouring grey days] (1979), one of his first expositions with photographs – two slide images of the sky merging into a single projection –, displayed an infinite number of possibilities, similar but always different. The manipulation of the possibilities of interaction between objects and with them, or of their processes of construction and accumulation, are defining factors even of the objects that Carlos Nogueira takes into the art gallery. This performative element is reinforced by the reversibility of the materials he uses in his works, which makes them more akin to happenings than to stable objects, and keeps them open to recombination and change.

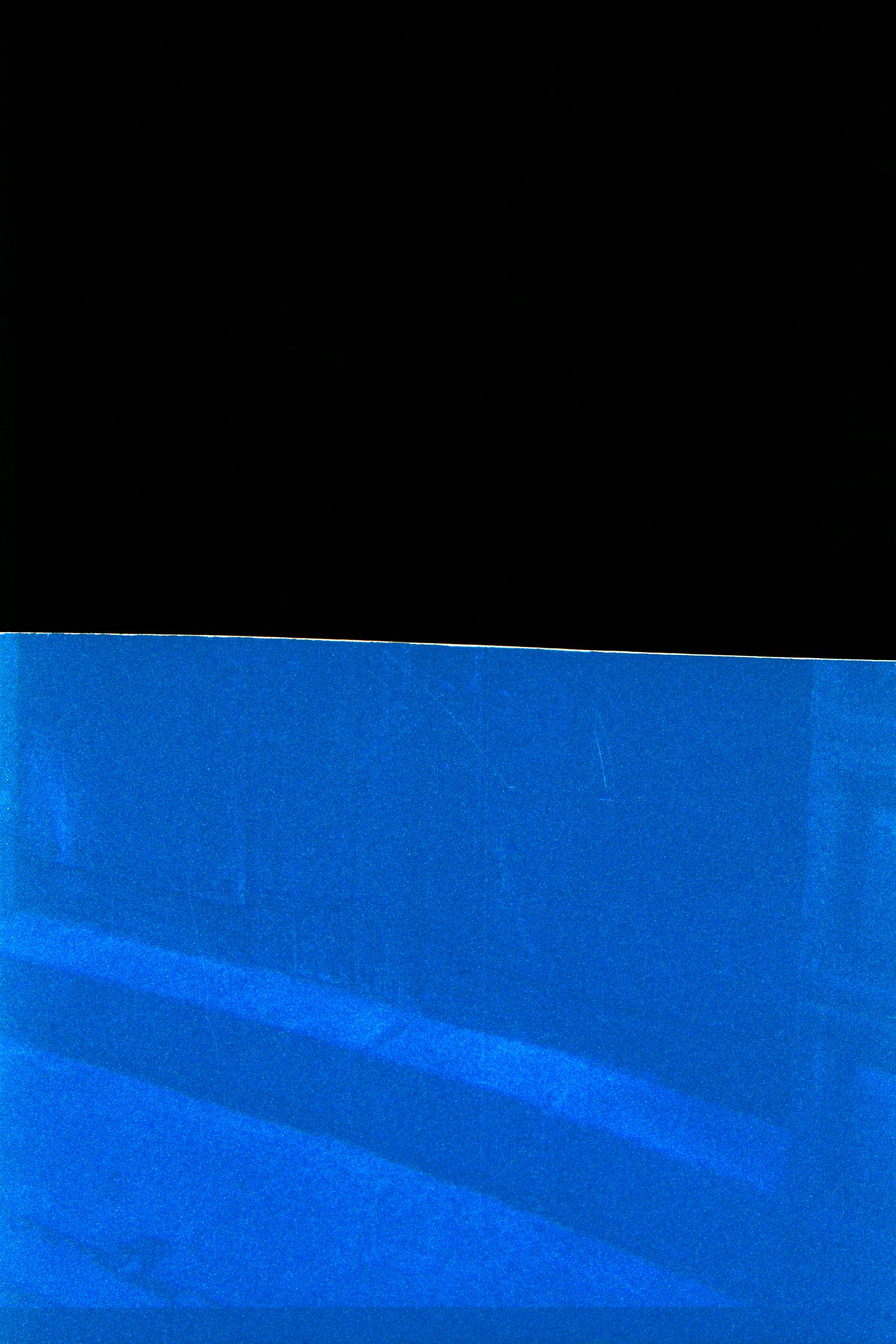

Immediately after making his landscape(s) to be sent/given away, Carlos Nogueira intervened on them. He covered the visual texture of two sets of postcards with oil pastel – white and black –, saturating their surfaces with matter. Combined in pairs, and marked by the horizontal and vertical lines of the collaged postcards, they function as a false reflection, a fusion of opposites. If to some extent the postcards never ceased to be images of the sea, the land and the sky, and despite the deliberate effort to render their visual referents abstract through the montage, it was by giving substance to the already visually suggested texture that these objects lost their visual referent and materialized. The original landscapes in the postcards were made invisible by the accumulation of interventions. Described by the artist as a noite e branco [the night and white], these intervened landscape(s) to be sent/given away effect a shift from the experience of the landscape to the experience of light and time, moving the referent from the remoteness of contemplation towards an almost epidermic closeness.

Some of the images on display are enlargements of the light-burnt edges of photographic film strips. While restituting a visual quality to matter, these impossible images are also material evidence of the deletion of the visual field, or of the limits of the photographic experience. This hard to stabilize juxtaposition reveals itself in the accumulation of reflections across the glass panels resting on iron brackets of beyond the very edge of the earth (1998). As is the case in the landscape-postcards, the geometry and the overlapping of the glass panes leaning against the wall outline and detach the images from their surroundings. But these landscape montages erase the paradoxical transparent materiality of glass, showing only the images reflected on it. Photography allows us to capture that contact zone in constant mutation that reveals the fluidity between image and matter, without ever taking on a definitive form. This accumulation of reflections marks a work that ceaselessly unfolds within a vortex of appropriations, constructions, offerings and transformations which can only be grasped through an immersive leap into its complexity and multiplicity.

Paula Parente Pinto

Footnotes

- ^ Charles Baudelaire, «Correspondences», The Flowers of Evil (trans. Richard Wilbur).

- ^ Catarina Rosendo traces the trajectory of these landscape(s) to be sent/given away in «Um acontecimento irrepetível prestes a acontecer de novo», in Carlos Nogueira. O lugar das coisas. Lisbon: Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, 2012.

- ^ Charles Baudelaire, «The Modern Public and Photography», in Alan Trachtenberg, Classic Essays on Photography. New Haven, CT: Leete’s Island Books, 1980 (third printing), pp. 83-89.

- ^ Jean Baudrillard, O Sistema dos Objectos. Brasil: Editora Perspectiva, 1993 (Éditions Gallimard, 1968), p.14. [The System of Objects, London: Verso, 1996.]