THINGS SAID TO SILENCE, SILENCED THINGS

Paola D’Agostino

At Instituto Inhotim, a wonderful Brazilian museum dedicated to the relationship between art and nature, there’s a transparent gallery called Sonic Pavilion, a work by artist Doug Aitken. It is a glass cylinder, where we sit in the embrace of the landscape while listening to the amplification of a sound, a single sound, composed of multiple noises. It's a kind of deep, full-bodied breath. It comes from a point on the ground that is the exit port of a sound recording, the last section of a channel excavated in the earth through a well 202 meters deep. The sum of the noises produced along the path, from the bottom to the surface, is the inner life of the earth's body (sand, rocks, tremors and shocks) captured through a microphone, or rather, a sequence of microphones placed at successive points of the channel. What we hear is the voice of the subsoil, a powerful sonic register that literally cuts through the silence to reach us. A rescued silence. Writing — I think — is nothing more than that microphone, the instrument we use to probe the deepest place of our universe, allowing an indefinite sound to cross the void and become shared, shareable. Better yet: writing is the full set of microphones, positioned at different points along the channel so that they can capture the different material moments of breath. The sound that reaches us depends on where we place the microphone — on where we place ourselves in the flesh of the text as we capture the resonance of things. Thus, the point from which I will decide to position my writing will depend on the resonance I will be able to give to the words. This is why I decided to place this account precisely here: in this letter that I am addressing to you.

Mother, mamma, mum: I write to you in this language that isn’t mine, ours, because a language that is entirely ours does not exist, nor has it ever existed. We are the utopia of language, you and I. I will never have a mother tongue, I suppose, because I never spoke with you, to you, consciously. The last time you were by my side, alive, I was 2 years old and you were 39. What words did you say to me? What words would I have tried? Will they suffice to compose a language – a mother tongue? Now I'm older than you with each passing day (strange, you know? profoundly strange), my life is split into two languages, I've lived half my years in each and I no longer know which is the first language, which is the second. What I know for certain is that between one language and another there are borders, mountain peaks followed by valleys, and in between, tunnels, that are sometimes crossed instinctively, other times with difficulty. The sum of these crossings is my everyday idiolect.

That’s why I’m so intensely fascinated by all the scripts in the world that manage to bring to light the work – done, in fieri, to be done – of crossing the space of silence, and the urgency of doing so, fierce enough to achieve beauty. Because every signal that is produced, coming from the depths of the earth, from the depths of our flesh-text, is a fruit, the fruit born by an explosion, a fire. What we get to see doesn’t always reveal the fire that sets it off. On the way to language, every sign is a bud. And what really matters, art, is the moment when the life of the matter produces the bud: the path that is taken between emptiness and resonance. And what one can thus salvage. For this reason, I started to compile a collection of pieces classifiable under the label of “figures that cross the silence”.

Things said to silence, silenced things is a verse by Paul Celan. And it is also the name I decided to give this collection of epiphanies of mine, instant images that manage to rescue the inner life of language. It's a collection that I've been putting together for many years, but didn't have a name for. Before finding this verse by Paul Celan, before the explosion that the clash with this verse caused.

I won't be able to show you the entire collection here. It would be impossible in the duration of one single letter. But I promise to continue the guided tour in the future, to make this collection the unfinished space of our correspondence. For now, you have here a small selection of pieces, organized in order of appearance in my memory. — Yes, memory is yet another way of crossing the silence, of course!

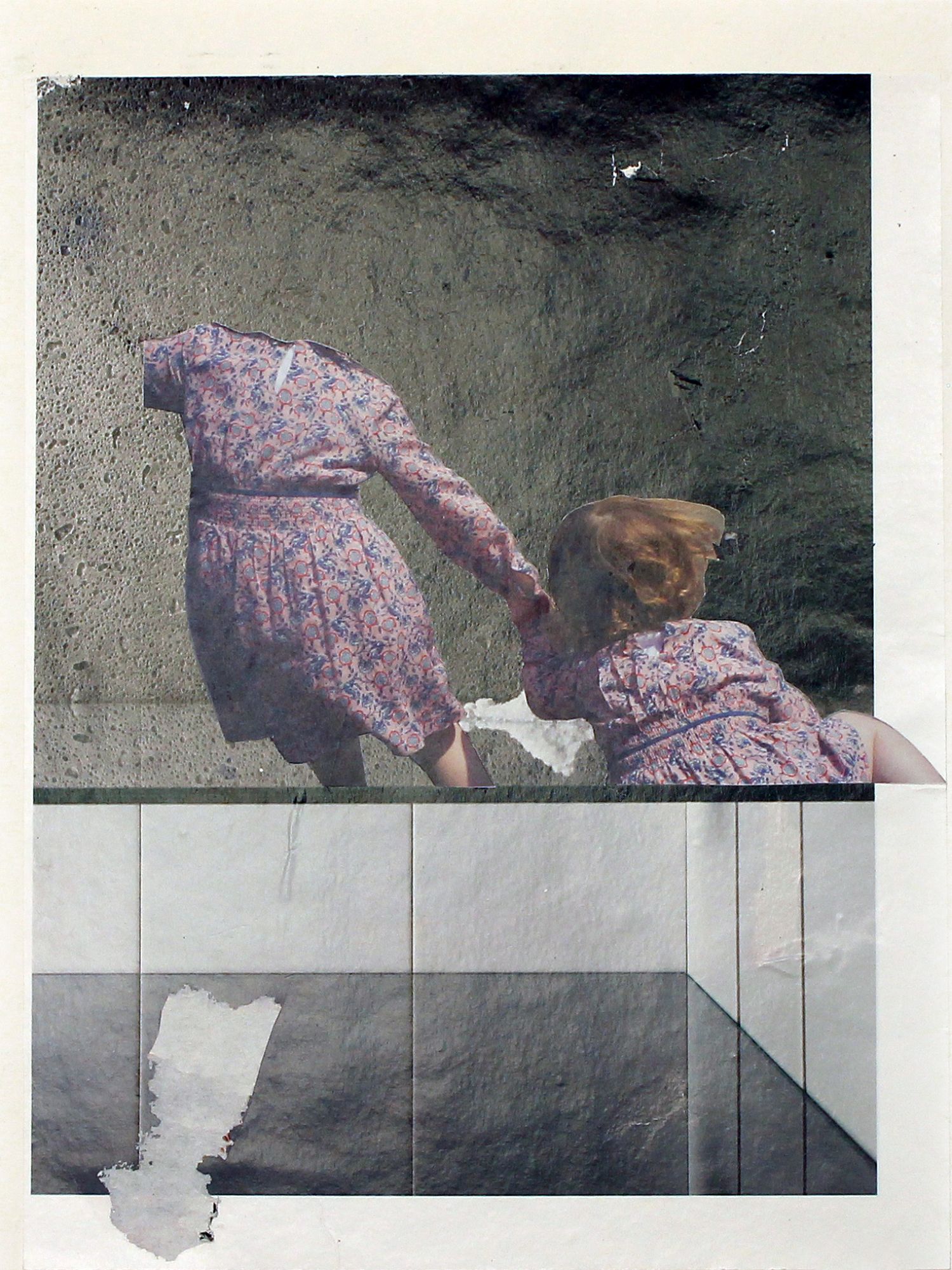

The first thing I want to show you is a collage by Nina Fraser called Escape. In her artistic practice, Nina reflects on issues such as repair, reconstruction, trauma perception, worldliness and home. Her creations are born out of mini implosions and sometimes the opposite, to use her words, in her language. In the clash with this collage by Nina, I felt a detonation that took me several days to verbalize. Then I understood that the restlessness, the astonishment that the image had caused me, was a silence that I should inhabit. That I should cross. And here I go. I take your hand, and I let myself be carried away by this feeling of helplessness – actually the right word to describe this feeling would be smarrimento, but I can't find its perfectly equivalent term in Portuguese. The right word…

As I told you, the title of this collection is a verse by Celan. Another verse of the same poem lends its title to Tempo do Coração, published by Antígona in 2020, translated by Claudia J. Fischer and Vera San Payo de Lemos, which records the correspondence (or the utopia of a lover’s discourse) between Bachmann and Celan. In a letter that Ingeborg wrote — from Naples — to Paul Celan in July 1958, one reads: «and I, for now, don't know the word that can encompass everything that contains us». Everything that contains us: this collection that I now show you is the quest for a word where the body of life can find itself, for a moment, whole, crossing the threshold of trauma, or erasure.

Speaking of erasures, there’s something very special here that I want to show you. They are animals, see? Animals rescued from the process of translation. It’s true. In the field of translation, there are many things that are lost during the transition between languages. These animals, for example, were in a poem. In translating from one language to another, the translator - although skillful - had chosen to privilege rhythm and rhyme, but this option had so altered the original that in the end, in the target language, the animals that inhabited the verses had completely disappeared. The revision work served to restore to the twilight landscape painted by the poet what had been lost in translation: a sparse tenderness of bleats and birds’ agonies. That is, the sound of the landscape. What really matters is that from now on, in the translated poem, it will be possible again to find bleats and squeals echoing in the life of that landscape, what matters is that sheep and birds managed to pierce the hole of silence and come out into the light of reading.

Other animals that I’ve kept here are these little bunnies. I took them from a short story by Cortázar called Letter to a Young Lady in Paris. The protagonist of the story generated bunnies uncontrollably, so numerous and unexpected that he was no longer able to manage them and suddenly, without realizing it, he let some slip into my book while I was reading it. And now here they are, living with me, reminding me relentlessly of the pervasive power of imagination.

Here, right next to imagination you have an interstice, see? It's the irony: all the distance we voluntarily install between what we say and what we mean, all the effects, the figures of style, the pirouettes that a sentence can take to deliver a message without delivering it completely.

Ah, look! This is the bottle of secrets. As we grow, time holds more and more secrecy. And yet, mine is a time without secrets. Everyone exposes their inner life in shared places, their most hidden affections, in a constant showcase of intimacies. I would never be able to share you on a network, mother, to show you to strangers without being sure that they would know how to read your story with the care that you deserve. Writing to you here is something else, there’s another time here, a hiatus, an intimate place that manages to preserve what Derrida called A Taste for the Secret. It's a form of modesty that I don't know how to renounce. Perhaps it’s the only one. Anyway, I'm not very prudish, as you can see from the contents of this bottle! You are my biggest secret. But there are others, that I’m not aware of. I will tell you about these in my dreams...

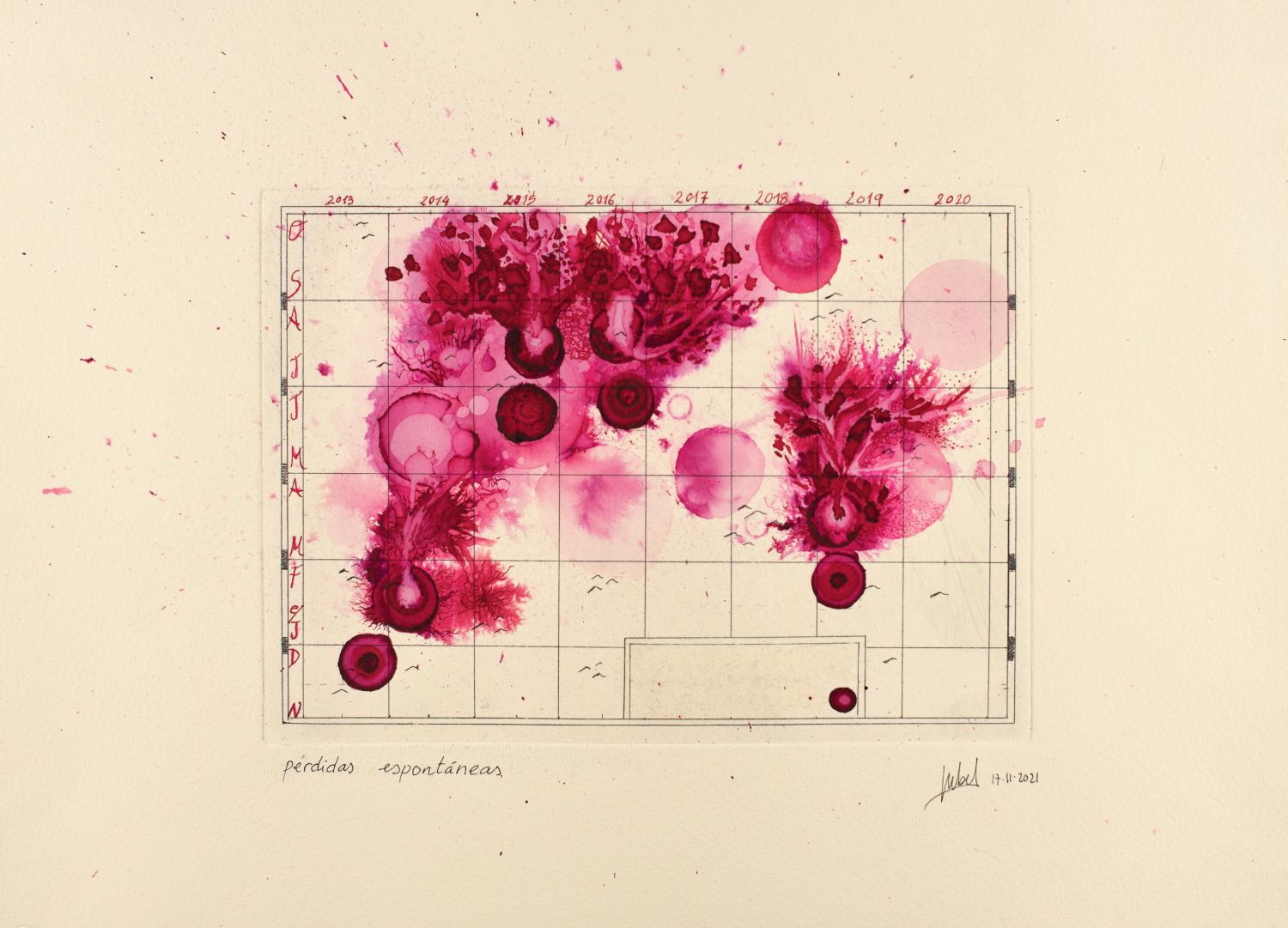

Speaking of dreams, there's one last thing I want to show you. It’s midway between secrets and things revealed, it’s on the precious list of explosions that manage to break the glass of silence, fierce enough to achieve beauty. It’s a work by Isabel Zarazúa, an admirable artist who for many years has cultivated a living dream: in the deep flesh of her body, she wants to be a mother. She initiated a complex process, a sequence of undertakings and defeats, attempt after attempt, a tenacious determination. Look at this magnificent watercolour: who knew? Isabel decided to map her lost occasions, entitling the work Pérdidas espontáneas (in Spanish, her mother tongue). Isabel's work is part of a collaborative project of an incomplete map, conceived by Constança Arouca and Madalena Parreira, for an exhibition called ƧPAM. Artists and scientists from different areas were given an engraving containing a base map and were asked to record on the white graph something they would like to see mapped, anything, using any inscription process. Isabel mapped incomplete pregnancies, aggravated by late motherhood. She shared an experience that is fairly common for many women of her generation, which is also mine. She considers that they are experiences that are not yet spoken of naturally, that remain behind the veil of silence, like some layers of the subsoil that still can’t see the light or cross the silence.

It remains to be said that Isabel Zarazúa's and Nina Fraser's paintings are for me two points of the same inscription path: I found them both during a walk, on a winter afternoon. And it seemed to me, immediately, that they were in deep dialogue with each other. Something like Joyce's Ulysses (Dedalus/Bloom) in the feminine: a child in pursuit of an indistinct mother, a mother chasing the image of an indefinite child. Two impossible cosmogonies, the utopia of a language that can be called maternal, came together in the same narrative during a stroll through a shared city, in our case, Lisbon, on December 10, 2021.

The inscription path where they appeared was the text of a walk. Because a walk is evidently a text, where the script of our body in movement is the word that meets other words, forming dense sentences of meaning, common narratives. The sound that emerges from that encounter is the heart of a deep ground, the life that happens secretly and yet knows how to tell a collective story. By mapping their explosions, two artists managed to cross a silence that goes far beyond their own flesh.

It is necessary to know how to take the signs by the hand when we meet them on the way to language. To cross the silence, it is necessary to touch closely the heart of each sign, its essence. Touch its heart, with a sure hand, so that the whole body of life can fit in it. To search for the heart of the sign only makes sense if we can thus listen to the heart of the world, the vortex of our common ground. We will thus arrive at the point where our history and a history that could have been ours, coincide.

What emerges from that encounter is the orient of a pearl crossing the darkness. Through that glow I will write to you again, very soon.

IMAGES

1. Nina Fraser, «Escape», 2018. Wet-pasted collage, 21 x 30cm. Courtesy: Nina Fraser

2. Isabel Zarazúa, «Pérdidas espontáneas», 2021. Watercolor drawing on chalcographic engraving. Somerset paper, 100% cotton. 280x385mm. Courtesy: Isabel Zarazúa and ƧPAM project