Theory of Discomfort – Becoming Human

Marta AlvimIntroductory note:

Theory of Discomfort is a multidisciplinary project that reflects on human nature, the non-human world and the possibilities of their interrelationship. In this edition Theory of Discomfort presents a triptych-essay that, amid the borders of life, problematizes the notion of knowledge and of progress, while looking at the suffering of beings and the magic of life in the earthly challenge of existence.

Theory of Discomfort

Becoming Human

«It was a fundamental error on the part of Herbert Spencer to interpret the annihilation of surplus offspring as a “survival of the fittest” in order to predicate progress in the development of living beings on that. It is hardly a matter of the survival of the fittest, but rather, of the survival of the normal in the interests of an unchanging further existence of the species.»

Jakob von Uexküll, A Foray into the Worlds of Animals and Humans, with A Theory of Meaning. 2010.

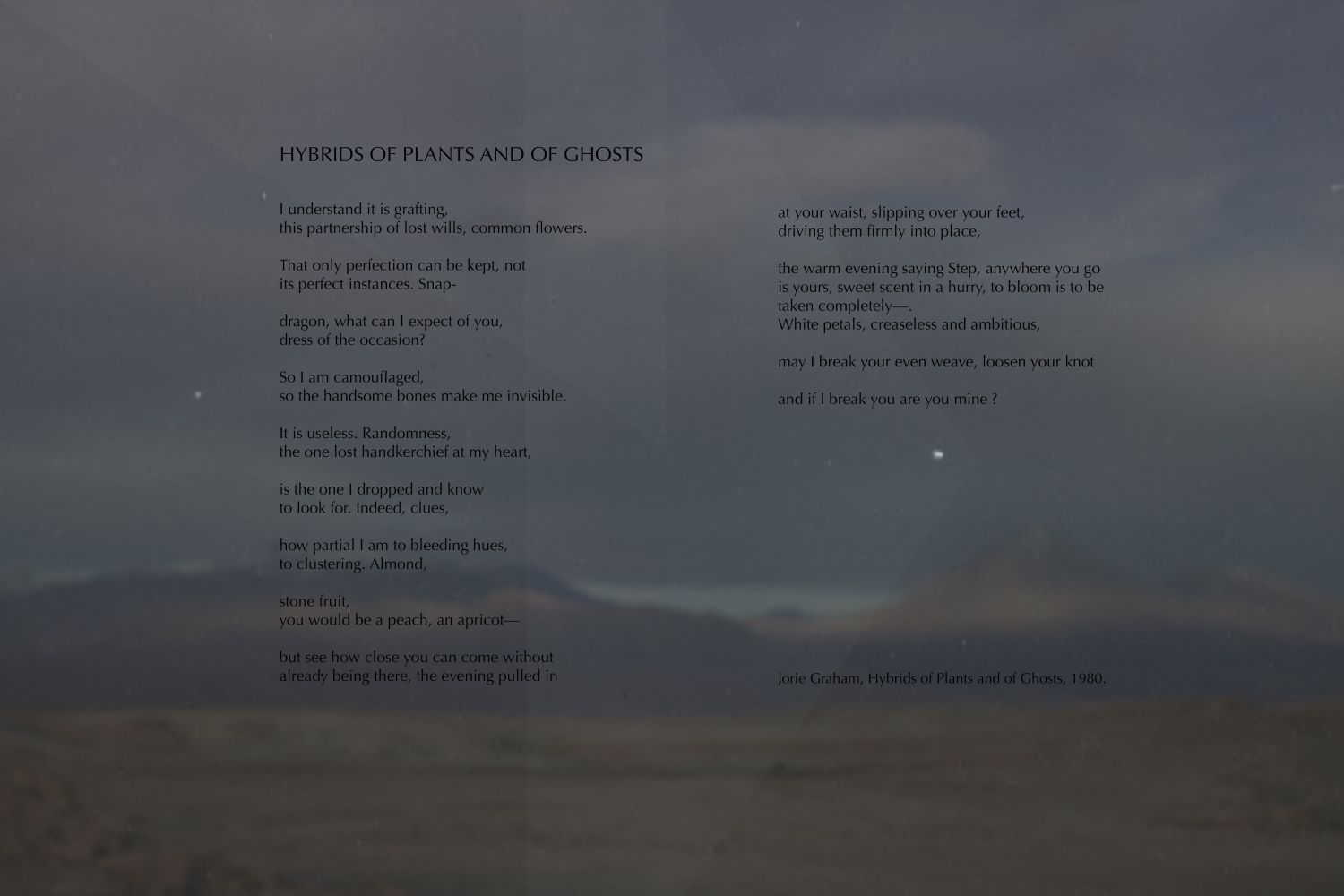

When renowned German biologist Jakob von Uexküll stated in 1934 that progress had more to do with the survival of the normal than with the survival of the fittest, he was not only making us rethink Darwin’s evolutionary theory but allowing us to wonder which parallel can we draw from evolutionist theory to human behavior. In what concerns the human species, it seems that it is not only our genes but the very nature of our thought and action, that tend to privilege the norm in detriment of the uncertainty of a future based in change and difference. The uncontrolled magic that often governs the progress of new rearrangements (hybrids and new species) might be too dangerous for the assurance of a future that, above all circumstances must remain secure, familiar and certain.

If, for instance, we take a close look at modernity’s normative idea of progress we will be able to recognize the inheritance of its values in our postmodern culture and realize that the postmodern world still feeds from modernity’s bias, traditions and fears. In nowadays politics and discourse, it is still possible to notice modernity’s call for reason and control, while subjecting all forms of knowledge to scientific validation. Familiar to the moderns would also be the perpetuation of the normalization of suffering and subjugation in the name of a progress that claims to serve human welfare. This notion of progress based on control, scientific hegemony and violence (the violence of capitalism’s exploitation), might be the veil that seems to fog our postmodern sense of wellness, giving us the sensation that, no matter how good or successful our life is, something awry is dooming our continuum, or, in other words, that something wrong will prevent us from a future (Marta Alvim, The Death of an Owl, 2012)1.

Nonetheless, instead of malign, this sense of (dis)comfort that numbs our relationships with the world, uneasing our trust in a future, might be instead taken as an opportunity for a paradigm change, a leverage to stop «searching in the past for the energy of the present» (Bruno Latour,2010,485), as no language of progress should be the language of oppression and domination for two-thirds of the world’s population and the entire non-human constellation. A problematization not only of the norm but (and mostly) of our relationships with the other (particularly the vulnerable other) shall necessarily occur to give progress a chance to rebirth, allowing Adorno’s paradoxical claim «progress occurs where it ends» (Theodor Adorno, 2003,130) to finally take place.

**

The problem of what it means to be human and in which ways can other beings ascend to the human qualification (in terms of rights, sentience, appreciation, etc.) interconnects questions of ethics, economy, and reliability (or self-confidence). If other living creatures could become human, how would one practice forms of exploitation that rely in difference and objectification? How could one still enjoy seeing in a zoo a gorilla whose 99% of human DNA couldn't prevent a life of displacement and confined isolation? Rather than acknowledging a fault, it often seems to be easier to continue seeing, for instance in gorillas, a thing, a beast or a monster (as featured in the movie King Kong) than to acknowledge their human gaze or behavior (Marta Alvim, Instinctive Behaviour, 2016)2.

Jakob von Uexküll once asked a «simple question»: «Is the tick a machine or a machine operator? Is it a mere object or a subject?» (2010, 45) But rather than simple, the answer is quite complex. The idea that lies behind Uexküll’s question points towards issues that are familiar to animism as it encompasses the belief that all that exists might have agency and that there’s no clear boundary between the material and the immaterial world.

In animism, something that we might call consciousness exists not only in humans, but in other living animals and plants, as well as in other entities of the natural environment, as the water, the air or the fire. In the Eastern tradition, a form of consciousness envisioned as an ethereal fluid that pervades the entire universe, possesses, in Sanskrit, the name of Akasha or Akash. The belief in a world animated by all sorts of entities and forces is also «what lies at the root of all the critiques of environmentalists as being too “anthropocentric” because they dare to “attribute value, price, agency and purpose, to what cannot have and should not have any intrinsic value» (Bruno Latour, 2010, 481). The idea of giving agency to what rationalists consider things, immediately give some sort of New Age flavor to the efforts of a paradigm change, braking the work of many thinkers that try to go beyond the constrains of materialism.

As highlighted before, if we assume that all life has an intrinsic value, then there’s no possible division between man and nature. This puts in question our very own right to have been establishing for so many centuries a biased division that only privileges a small part of the living population. The idea that all what exists matters, encourages us to think that we need to have a different democracy, a democracy that can be extended to all things. Latour explored this possibility in his Parliament of Things, a parliament where all natural and social phenomena as well as discourses about them were not seen as separate objects to be studied by specialists, but as valuable agents that should have a seat and a voice in the organisms of power. Latour’s attempt to reconnect the social and the natural world by arguing that the modernist distinction between nature and culture never existed, acts directly in complex and timely issues as racism, animal rights, women’s rights and climate justice, allowing such issues to become more real, more tangible, and therefore more possible to be addressed.

Not picking any group in particular, Latour’s parliament attempts to protect life from human reason, violence and exploitation. But, despite its attempts to bring more justice to the planet, the Parliament of Things might be incurring in the same danger of using the so rational utterance things to designate both the living and the non-living (Latour argues that we should give rights both to nonhumans, to quasi-objects and to hybrids). In my opinion, the elimination of difference between the living and the non-living might contribute to the perpetuation of the sense of doubt and confusion that we are already immersed in, as it is not in the act of undifferentiating, but in the ability of embracing difference in a non-antagonistic way that dwells the possibility of achieving a positive conviviality.

Beyond this, while Latour’s things try to serve both the bird and the mountain, it fails in unriddling the problem of suffering. Maybe an investigation on suffering should be heartened in order to search for the boundaries of life and the boundaries of difference, in a final attempt to retrieve the vital substance of our fragile planetary humanism.

1 The Death of an Owl - https://vimeo.com/user4849367

2Instinctive Behaviour https://vimeo.com/181335088