The «Objet Trouvé» and «Das Unheimliche»

Susanne Müller

Today again I'm waiting for nothing else than my only availability,

than this thirst for roving towards everything.[1]

(Andre Breton, The equation of the found object)

Is there anything more subjective than an objet trouvé, this kind of «found» object whose «objectness» lies in a subject's glance? Mostly, the objet trouvé must loose its original raison d'être to become this new thing with a new meaning. That's one of the reasons why it is both an objet trouvé and an objet perdu (lost object). The German language distinguishes between finden (find) and erfinden (invent), two verbs that seem to coincident in the French trouver (inf.) in objet trouvé which is always the invention of something new, though it might be based on the ancient. That's why it can be art.

It's between the found and the lost, between an active research and a passive alertness similar to the equal attention in psychoanalysis (that might require of the subject a kind of «lost of self»), where the experience of objet trouvé happens to be, in that same interstice of time and space where the coincidence resides. It's neither exclusively in the «objective» and object's world nor in the subject's view, but in the in-between, where the novelty of the existing can come to consciousness. Thus, the objet trouvé, taken as the happening of the trouvaille (finding), depends on someone's recognition and, more generally, on someone's consciousness of having found what was lost in the marsh of indifference. Because of its anchorage in the ordinary context, the objet trouvé is susceptible to stand out of it. Once again, the objet trouvé turns out to be a paradoxical phenomenon, questioning the borders of what is ordinary and extraordinary, of what is consciously seen (visible) – in the best case, seen as if «never seen before» (jamais vu) – and unseen (invisible as being too much déjà-vu).

The French word objet trouvé itself, that sticks out of the English language as a foreign body, emphasizes this paradoxical inside-outside-relation. The term is inside the language and outside of it. To be completely understood, it needs another, an outer reference – the French language and the surrealist context – which necessarily brings the risk of misunderstanding, whereas its translation, «found object», leads to an impoverishment and a decontextualization that, again, entails the risk of a falsification. This literal untranslatability puts the objet trouvé in one range with das Unheimliche, whose English translation «the Uncanny» turns out to be insufficient. This linguistic common ground is by no means the only parallel of these two concepts:

As Freud points out in his eponymous text The Uncanny from 1919, the German adjective unheimlich (literally «the unfamiliar») is characterized by its paradoxical signification in which the two opposite meanings «familiar» (heimlich) and unfamiliar/foreign/strange (unheimlich) coincide. This leads Freud to his definition of «the Uncanny» as a feeling that «which leads back to what is known of old and long familiar»[2]. In other words, «this uncanny is in reality nothing new or alien, but something which is familiar and old-established in the mind and which has become alienated from it only through the process of repression».[3]

Thus, das Unheimliche, just like the objet trouvé, is based on the extraordinary character of the ordinary. It presupposes the recognition of the familiar as the foreign, the strange or surprising, or the other way round. For Freud, it is a forgotten (repressed) memory stepping out right from the unconscious that characterizes the experience of das Unheimliche, most often triggered by the encounter with a strangely familiar object. Therefore, the Uncanny becomes an image of the unconscious itself and, like the dream, it could be taken as one way to understand the mechanisms of the human psyche. Since it's first of all an outstanding sensation, das Unheimliche is comparable to the surprise accompanying the moment of the trouvaille of the objet trouvé. Although it is mostly associated with an «uncanny» fright, it can evoke indeed one's enchantment, too.

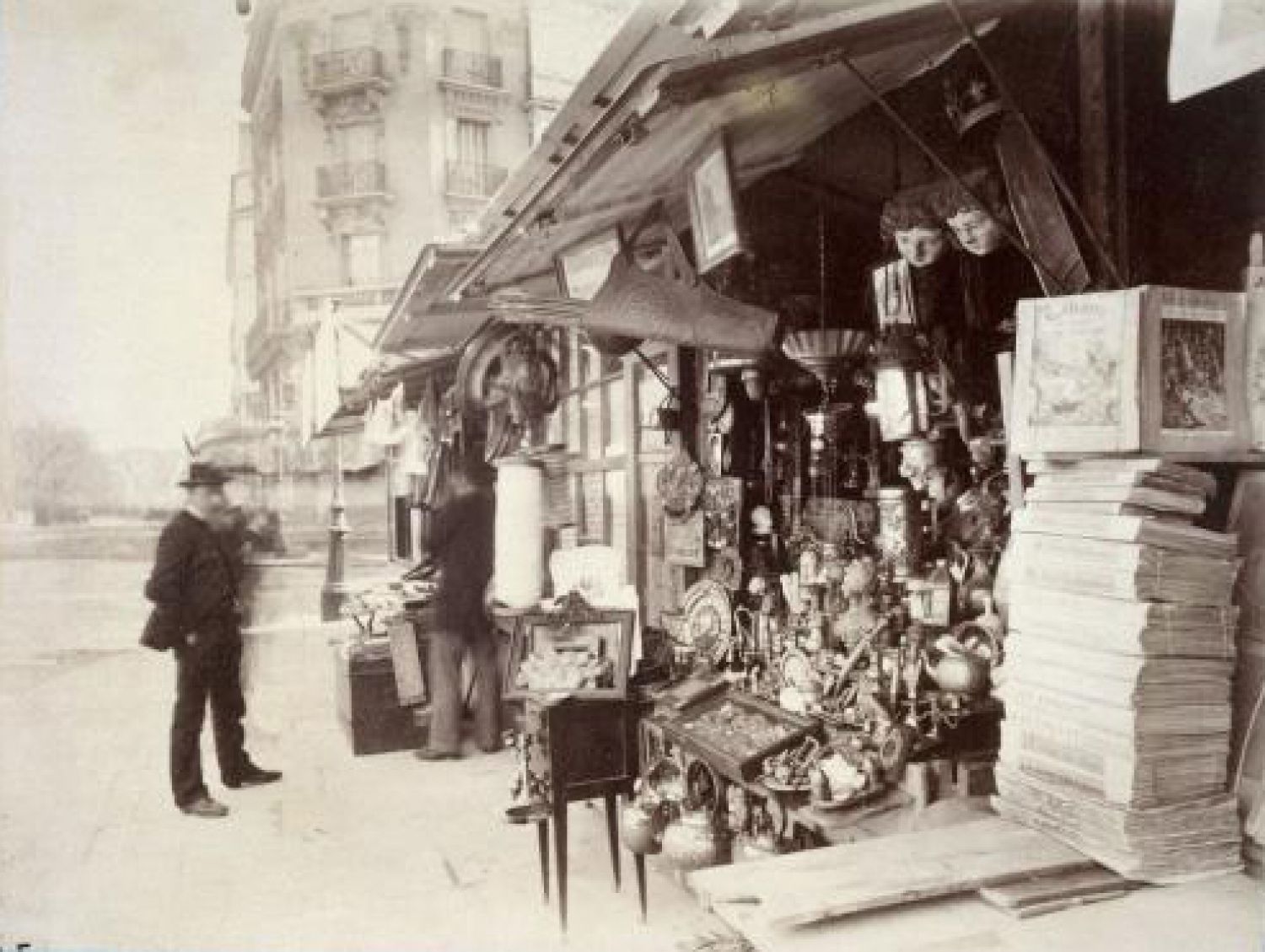

André Breton definitely knew Freud's theory, but did he also read das Unheimliche, this rather unknown, not to say forgotten text in the corpus of Freud's writings, re-discovered only in the 1960s and 70s by French theorists like Lacan and Derrida? In The equation of the found object, the Surralist's leader points out the close connection between the objet trouvé and the dream and shows that he's perfectly aware of the function of both of them. He notices indeed that «the finding of the object fulfills here rigorously the same function as the dream, in the sense that it frees the individual from paralyzing affective scruples, comforts him and makes him understand that the obstacle he might have thought insurmountable is cleared.»[4] In Breton's eyes, the objet trouvé not only corresponds to «a more or less unconscious desire»[5] – like in his own example a strange spoon's handle which turns out to represent the shape of Cinderella's slipper, image that haunted Breton while running into that crude home-made spoon on Saint-Ouen's flea market – but it is also able to set free the affective charge that was bound in the unsatisfied (and maybe denied) wish, at least if this wish is recognized as such.

The discover of the objet trouvé is ideally followed by a second discover, removing literally the cover or masque (a masque is by the way the first objet trouvé that Breton and Giacometti track down at the flea market) of the unconscious desire (that becomes conscious and can be admitted) which lies behind the choice of the objet trouvé as an objet désiré (desired object). So one of the objet trouvé's functions seems to be to give shape to a desire or in other words to model an unconscious image that lays behind the speakable. Originated in the viewer's unconscious, the desire gets incarnated: the object embodies the latent image which then becomes «objectified». The objet trouvé suddenly appears in front of us (from objectum, «thing put before», «something perceived or presented to the senses»), it catches our eyes and our attention, because secretly it corresponds to what we carry insight of ourselves. Breton's concept of an objective chance is close to this idea of secret arrangements guided by our desire which can also appear in a piece of art.

Like the word «projection», «objection» goes back to the Latin verb jacere that means «to throw». Some inner thing is thrown outside, it's projected in the foreign (unheimlich) world, to be then recognized in an «object» that actually is a familiar (heimlich) one, belonging to the self. Like in the Freudian conception of «the Uncanny», the foreign/strange and familiar go together, they coincide in this surprising experience that characterizes as well la trouvaille as das Unheimliche. In both cases, the objet trouvé proves to be closely connected to an objet perdu, once present and conscious, but now «lost» to consciousness, repressed or forgotten like an unadmitted desire or an unbearable anxiety, that often goes back to early childhood when the subject didn't yet have the perception of his own body as a (possible) entity. For Lacan it's the «object a» which is the object of both desire and anxiety, that turn out to be intimately linked.

Therefore, the objet trouvé-perdu helps us to understand the subject facing his own desire and anxiety. Both of them only become tangible in the encounter of the «other», thrown accidentally in front of us and calling for our glance capable to recognize it as the object of desire, catalyst for the most strange and familiar experiences, keeping us in touch with the unheimlich traits of ourselves.

Footnotes

- ^ «Aujourd'hui encore je n'attends rien que de ma seule disponibilité, que de cette soif d'errer à la rencontre de tout», translation of the author.

- ^ Freud, Sigmund (1919). The ‘Uncanny’. The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume XVII (1917-1919): An Infantile Neurosis and Other Works, p. 220.

- ^ Ibid. p. 241.

- ^ «[...] que la trouvaille d'objet remplit ici rigoureusement le même office que le rêve, en ce sens qu'elle libère l'individu de scrupules affectifs paralysants, le réconforte et le fait comprendre que l'obstacle qu'il pouvait croire insurmontable est franchi.» Breton, A., «L'equation de l'oebjet trouvé», Documents 31, no 1, juin 1934, p. 24. Translation by the author.

- ^ Ibid, p. 21.