'In the United States, the landscape is so huge it takes on a quantitative meaning and therefore becomes a political quality.' – Heiner Müller

If, as Duchamp believed, art is a mirage, then art presupposes the existence of desert – not as a geographical feature, but a deserted place, a wide and potentially infinite landscape made available to human imagination and in which the invention of a whole other world is a possibility. The desert, this foundationally void space, becomes a site for the projection of an imaginary and hallucinatory reality announced in the vortex of the horizon line, a locale where visions that are possible and representable only within the realm of art are trafficked. The mirage, and therefore also art, is a visual forgery, a superposition of mythology over reality.

Fiction, as a system for the production of signs and narratological operations, is essentially mythomaniac. Fiction creates a discourse which is intended to intervene in the landscape – capturing it, expanding it, filling it, fragmenting it, destroying it; in short, somatising it, saturating it with the hallucination of reference and the false prophecies contained in the mirage, which refer to the uncertain and anti-topographical address of literature. The landscape of fiction is deserted not because it is void but because, devoid of borders or thresholds, it is a space without morphology or a system – this is why the natural world, with its virginal aura and its appearance of an amnesic capsule (plan of utopia and ucronia, where there is no time, only duration), exerts such a strong attraction over the writer’s sight. It is in the forest, in the mountains, in the sea, in the plains and, naturally, in the desert that the narrative can leave its deepest marks and fulfil its mission: to inscribe its signs as if they were cracks and incisions in matter. The primordial mission of literature is therefore to occupy space and industrialise the landscape with its mythomaniac obsession.

From a geopolitical perspective, the United States of America are an astonishing work of fiction that established itself as the dominant cultural standard. ‘America’ (a country that, as if by some sort of black magic spell over the collective imagination, usurped and adopted the name of a whole continent) was created from a blank space and a vast unoccupied landscape, if we don’t take into account the ‘uncivilized’ indigenous tribes whose existence in memory is due to their contribution to the invention of a film genre suited to the production of an ideological discourse and, yet again, the creation of the American myth. Its capture was absolute and based above all on the idea that a vast and empty place offered an opportunity for escape, which for Deleuze constitutes the most creative act of all: to escape is to draw maps based on which ‘worlds are discovered’. All that immeasurable territory, without history or system, was left at the service of the drawing of lines from imagination, ambition, excessive dreams and even an aspiration to transcendence, acting as the potential laboratory and foundational space of post-history, the history that invents itself and exhausts its own present.

The triteness of the expression ‘American Century’ (referring to the timespan between last century’s post-war period and the advent of the new millennium) belies its pertinence by focusing its immediate meaning on the issue of power. But the hidden core of its meaning consists of the signalling of the emergence of an anti-historical time (or an historical anti-time) and the realisation of a mythomanic mirage that generated the habitat of Nietzsche’s ‘last man’ – the man who, according to Peter Sloterdijk’s interpretation, having abandoned the idea of ‘a universal and impersonal intelligence’ achieved through us, sees intelligence as ‘private property (...), a kind of capital that is invested by men (...) on themes and projects.[1]’ Or, in Heiner Müller's elliptical words: ‘Intelligence without experience: this is what I mean with America.[2]’

United States of Amnesia

The metamorphosis of landscape and the metamorphosis of the human being projected and transmentalised in the landscape is perhaps the main theme of William T. Vollmann’s novel You Bright and Risen Angels. In broad terms, its plot describes a war between the reactionary forces of electricity and insects, joined by a bloodthirsty gang of humans exalted by revolutionary ideals, throughout a period ranging almost a century, with characters moving as if they themselves were the elements the centripetal forces of History converge to. As the novel unravels, an intricate, kaleidoscopic mapping of insular and geopsychically codified territories (whether real or fictional) is established (Omarville, Cooverville, the Amazon forest, the Arctic, San Francisco), territories inhabited by characters marked by plastic subjectivity and a virtual existence, whose irradiating centre is America, perceived both as a political and cultural entity – the ‘great Republic’. The two polarising forces in the narrative are both mesmerised and inspired by the evocative power of wild nature as a space devoid of human presence, despite being archetypes of two antagonistic worldviews: Mr. White, the businessman who invests his capital in the generation of electricity so he can rule over the world, is a fanatic of progress, whose unstoppable advance will be only possible through the destruction and annihilation of landscape; Bug, in turn, is the terrorist militant of an anti-progressive environmentalism that sees in nature the last bastion of harmony and balance, free from the violence inherent to humans. The landscape Mr. White comes from is that of the mountains of Colorado, where in the early twentieth century he established his Society of Daniel, an evocation of the site where Nikola Tesla performed most of his experiments with high voltages but also reminiscent of other mythical places of science history such as Los Alamos, by the Rocky Mountains, where the atom bomb was created by R. Oppenheimer, whose confession – ‘my two great loves in life are physics and desert country’ – subliminally echoes in the narrative. On the other hand, Bug’s relationship with the landscape is defined by a feeling of maladjustment to the world that eventually turns into a syncretic ideology based on the quest to preserve nature from modern societies based in cities, those dreary necropolis inhabited by immoral beings that should be sent back to the country with ‘bullets of vanguardist light’, in spite of his suspicions that nature possesses its own system of collectivized murder. However, they both share a fascination for mirage and an ideal of transcendence that is projected in space, giving rise to a dialogical tension between their seemingly irreconcilable views of nature: on the one hand, the desert, the vast death where everything can be built and made all over again; on the other, the impenetrable and imperishable forest that extends everywhere and which sooner or later will inexorably override all human creation. We thus find ourselves in the domain of a dialectical relationship between fiction and its ghosts. Not surprisingly, the landscape does not stand up to its hyper-codification and is thus transported to a meta-historical and ucronic area, reconverted into the hard core of the foundation of a portable mythology. The characters are out of History, but they participate in History’s theatre, on a stage or a curiosity cabinet, with climate control and artificial features – an exhibition and formulation device. The places which they inhabit and traverse are spatial and temporal containers (snake tanks, swimming pools, summer camps, darkrooms, camping tents, houses in the forest and glacier bunkers) – self-sufficient and impenetrable universes, self-regulating domains outside our world (the wild and uncontrollable out-there, incomprehensible and chaotic) perceived by the author as prismatic spheres that provide him a reverse feedback of his own intra-delusion. The landscape is therefore made virtual in a petrified and vegetative picture of a world excluded from the cosmos, orbiting an invisible universe.

The background project stated here consists in a re-visitation of Walt Whitman’s literary program – x-raying the ‘body electric’ and the electric psyche, permanently subjected to cognitive and neurological stimuli, hyper-modernity and its corresponding anthropological failure. In this book, fiction is a breeding ground for the electrification of inanimate, inert, lifeless matter – simultaneously depicting a densely wooded landscape and nostalgia for trees, the desert and mirage. Vollmann creates an ideological and psycho-political microcosm saturated by a maddening traffic of communications, destitute of morality or any ultimate truth, where we find but one rumination (exhaustive, cathartic, convulsive) about void and the absurd hypotheses for filling up that void – creating a story that is captive of a globular perspective which, much like Escher prints, contemplates itself as its own miniature, now in a self-caricatured version. During this process, the author advocates the mythomaniac trait of literature, resorting to a double strategy of encryption (the metamorphosis of insects, encrypted in their archetypes and signs bringing up an ambiguous metaphor: are they an evocation of the Afghan Mujahideen fighting against the Soviet invasion? Or do they represent USA helicopters over the skies in Vietnam?) and miniaturization (the world inside a bottle or the world seen on a computer screen). All simulations and concentrationary spaces of the world's History and time converge in its distinctively American landscape.

With the onset of modernism, literature was faced with the need to depart from the assumption of dream as the driving force of the writer, and also with the need for reversal of its foundational paradigm, based on the realisation that it is the world that programmes realities alternative to the dream and the power of art. This new cognitive datum forced fiction to recentre on the diffuse and vertiginous vortex of the dream of itself, simultaneously developing strategies for escape through the complex web of unwanted dreams that colonise consciousness. Kafka’s The Castle and its excessive and meta-paranoid doppelganger in post-modernist declination, Thomas Pynchon's Gravity’s Rainbow, are two paradigmatic examples of such a change, indicating literature’s drift towards a new symbolic space for representation: placing at the centre of the fiction someone’s (the character’s) bad dream – a dream that abides by external plans masterminded by sinister entities and obscure powers (visitations). So there is a transition from the author who projects his dreams in fiction to the author who confronts his character with the dreams others project in it, as an agent who exerts a fluid force against his own circumstances as opposed to an inert and passive body that acts as a mere reflector and a device for the observation of reality (the suspicion of reality becomes the suspicious of fiction – never again shall our dreams be safe and protected from the ubiquitous influence of the fictions that sew reality together, from its visitations). In order to exit the dream, we must fall asleep – not wake up. Or, alternatively, dream within the dream and its endless echoes.

In one of its many possible interpretations, You Bright and Risen Angels may be read as the latest possible version of this approach to literature, no longer as a producer of mirages but instead as an instance of discursive mapping and mirage decoding. Its narrative is both dynamic and static. Nothing in the landscape moves – movement is fundamentally entropic. According to the literary concept proposed by Vollmann, the trauma underlying fiction doesn’t stem from a sudden awareness of the absence of an objective reality for fiction to counterbalance – an assumption that would entail a limitation of the literary version’s status to that of a simulacrum, a copy without a referent, a false testimony. Instead, such a trauma would originate in the abrupt realisation of the baffling and obscure fact that reality uses, and even exceeds in doing so, the same strategies as fiction. Therefore, the trauma is the same as that of a machine for the production of signs and narratological lines which, to use Heiner Müller’s expression, ‘always arrives too late in relation to reality’[3], a map that is not up to date with changes in the landscape, a speech that is posthumous to its event and its catharsis, based on a inarticulate view of an inarticulate world. The author creates fiction with the world's ‘last men’ and their many personifiers, including Mr. White and Bug, whom in Sloterdijk’s words would be the ‘masterless angels’ of a terminal historical time that refuses to accept its end, living in a quasi-religious ecstasy with the idea of their own existence. The necronauts of amnesia, fetishists of self-contained space, of climate-controlled and artificialized nature, inhabit the zone of the full and self-sufficient user of the world, which, like Pynchon and Tarkovsky's zones, seems to exhaust its own future or to provide the possibility of countless potential futures that exist only in the shape of paranoid deliriums or transcendental hallucinations. In view of such a necropolitical mirage, literature cannot but adapt its speech in the form of an obituary and the hypnotic litany that spans the book – ‘Oh, you bright and risen angels, you are all in your graves!’ – does not cease to remind us of that.

And yet, contrary to what the (also mythomaniac) prophets of the apocalypse, the catastrophe is not absolute. Vollmann does not parasitize the impasse or death because he refuses to see a corpse in History, even if it is a postponed one, choosing instead to focus on the larvae that parasitize and fertilise the body. The world appears to be impervious to absolute domination by cultural, symbolic and significant artefacts produced by humans and, despite the spectre of decay of all things hovering over the space, something grows insidiously, hostile and irresolute amidst the ruins’ debris. Even in America the mirage has its limits – the limits of the landscape that is impossible to industrialise, as Heiner Müller points out when he evokes the image of the ‘Mississippi valleys where factories rot in the swamps’[4], where the bargain is for rebirth, not death. There is always something that escapes the map, even when it exceeds the territory, as in Borges' fiction, explicitly quoted by Michel Houllebecq in a novel literally titled The Map and the Territory that ends with the brutal and clairvoyant sentence: ‘The triumph of vegetation is total’.

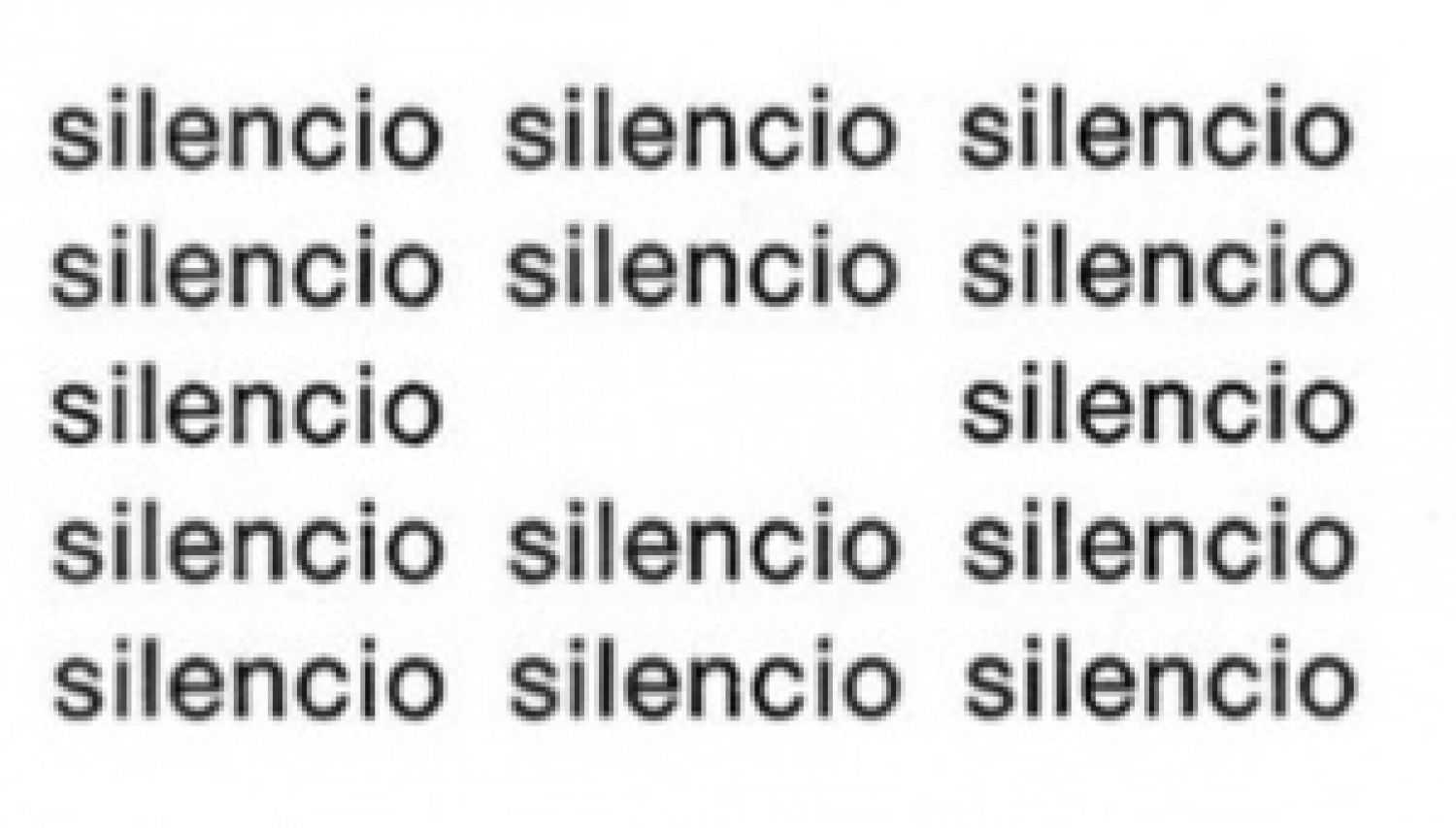

After the terror of the long and noisy night of the electric insects, fiction should wake up to the disturbing daydream of a new deserted landscape – a zone of electromagnetic silence – in whose horizon the eccentric mirages of the future shall germinate.

Author’s note

The novel You Bright and Risen Angels, by the American writer William T. Vollmann, was translated by the author of this essay. It was published in Portugal in 2014 by the publisher 7 Nós, which will continue to publish and disseminate Vollman’s work. The translation and publication of the works Europe Central and The Atlas is already planned.

Footnotes