Subversion of the article 175 of the Japanese Penal Code: three cases

Miguel PatrícioThe article 175 of the Japanese Penal Code prohibits the explicit representation of genitals in the overwhelming majority of cultural products (a few rare exceptions are made according to legal interpretation). This kind of censorship covered the last 150 years of Japanese history and has affected mainly cinema, an art as old as the application of this law, which dates back to the Meiji Era. We can argue that prohibition creates transgression and the social denial of explicitness engenders the symbolic and the subliminal. With three different examples, we will see below how Japanese filmmakers managed to circumvent censorship.

1. Kenji Mizoguchi and Tai Kato: the powers of the phallus

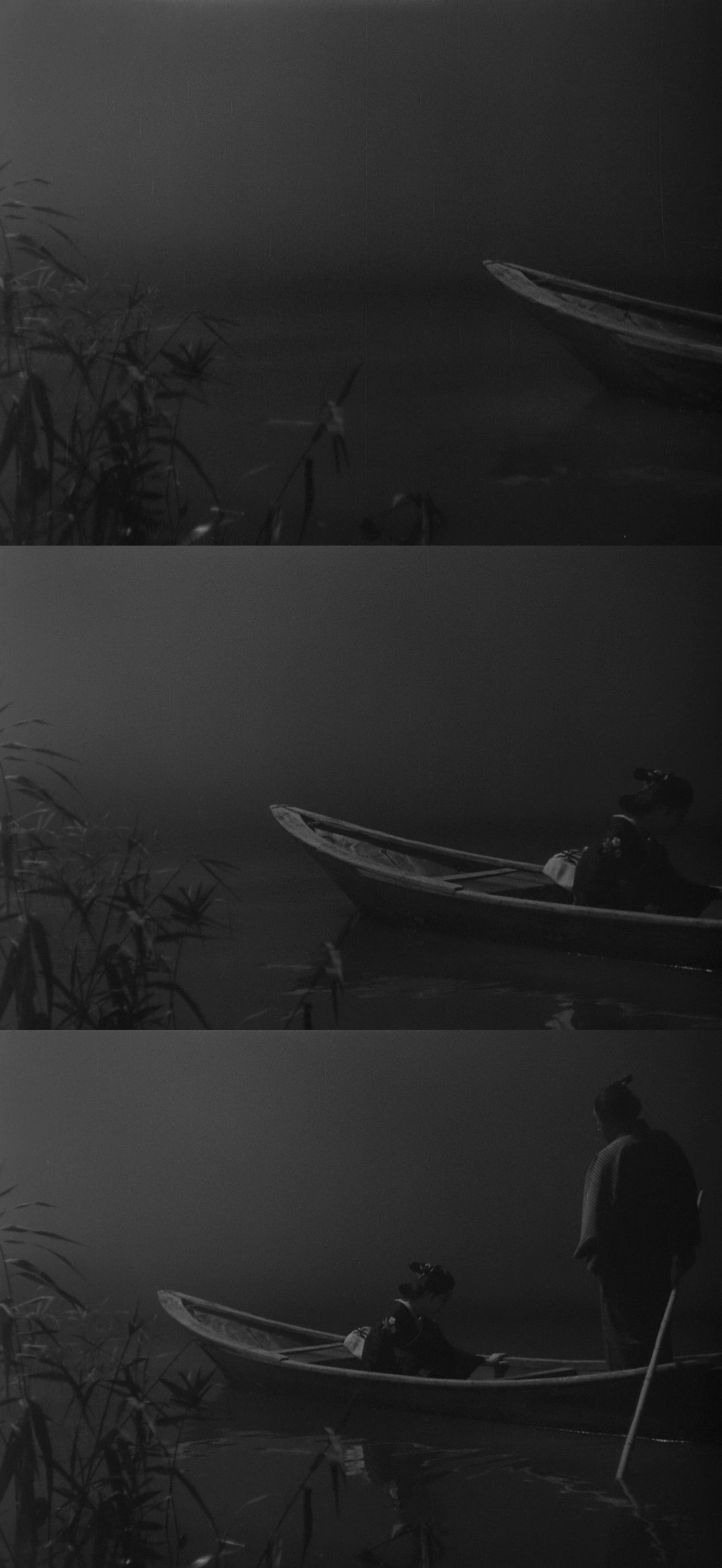

In A Story from Chikamatsu, a film loaded with erotic tension without a single kiss being depicted, Kenji Mizoguchi choses phallic suggestion to describe the moment when Mohei and Osan surrender themselves to passion and violate the social norms of their time.

The erotic power is introduced through a progressive invasion of elements in the frame. The phallic tip of the boat begins to break the serenity of the water. Then, the fragile Osan appears, followed by Mohei who stares at her with desire. We could argue that Mizoguchi already wanted to establish a symbolic hierarchy here: firstly, the phallus is being interpreted as the unifying entity of the lovers' fate, secondly, the object of desire is seen by desire itself and, thirdly, the drunken subject that can't handle the excruciating tension anymore. Emotional discharge follows as expected.

Mohei makes his advances quietly, keeping the role of the servant and is for the first time reciprocated. When this happens, the presence of the boat that was implied (since it ran the frame end to end) begins to take form and transforms itself in a phallic symbol again. The ecstatic reaction of Mohei plus the shot that closes the sequence with a fade-in (the empty boat, the water and the suggested carnality inside the hut) confirms that the characters became lovers for the first time.

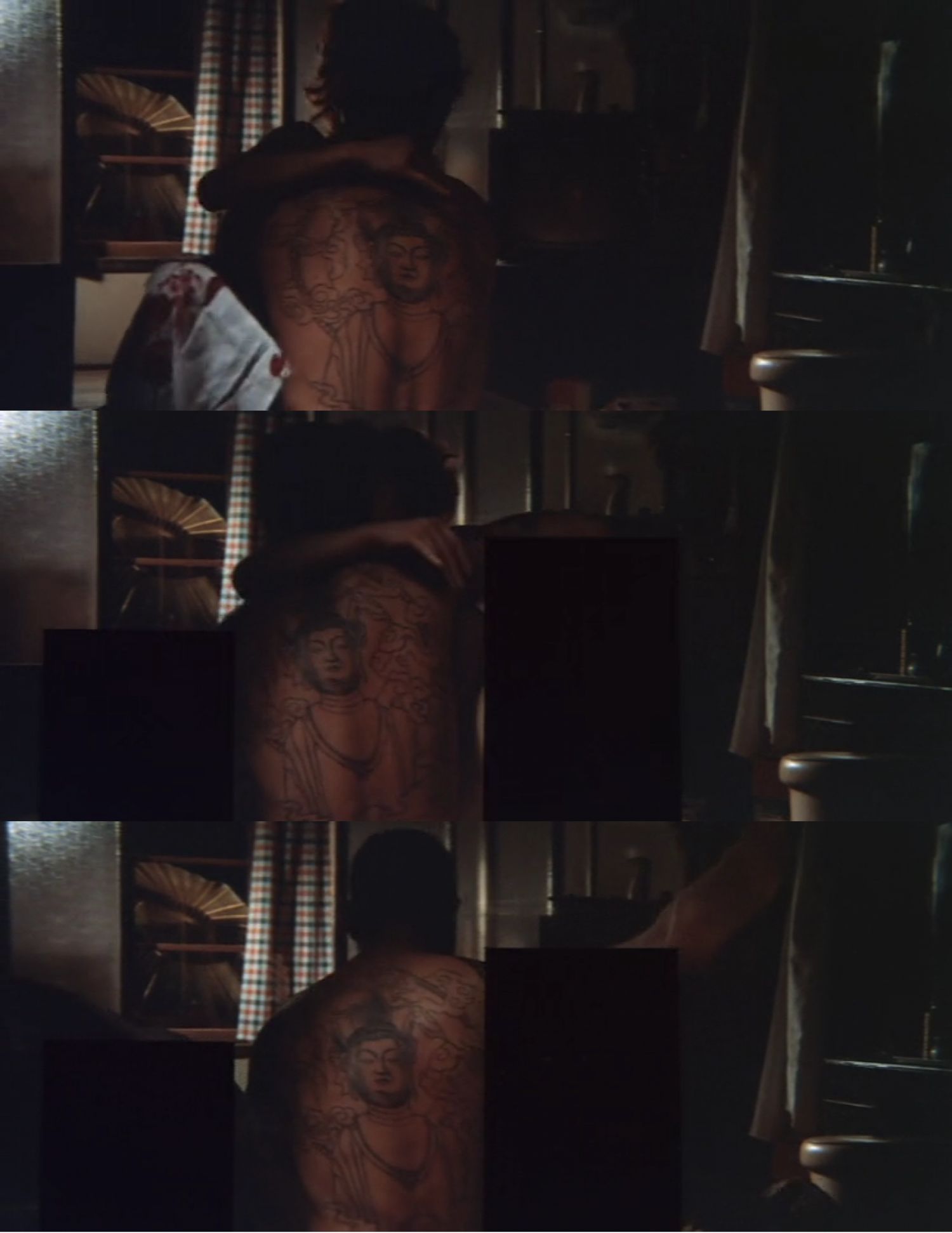

Tai Kato was another director who used suggestion to bypass allegations of obscenity, but unlike Mizoguchi who was more interested in erotic catharsis and wanted to redirect sexual activity to the imagination of the spectator, he configured the shots so that the phallic elements illustrated the depths (the id, if we want to be psychoanalytic) of the stoic characters that never fulfil the yearning of their carnal temptations.

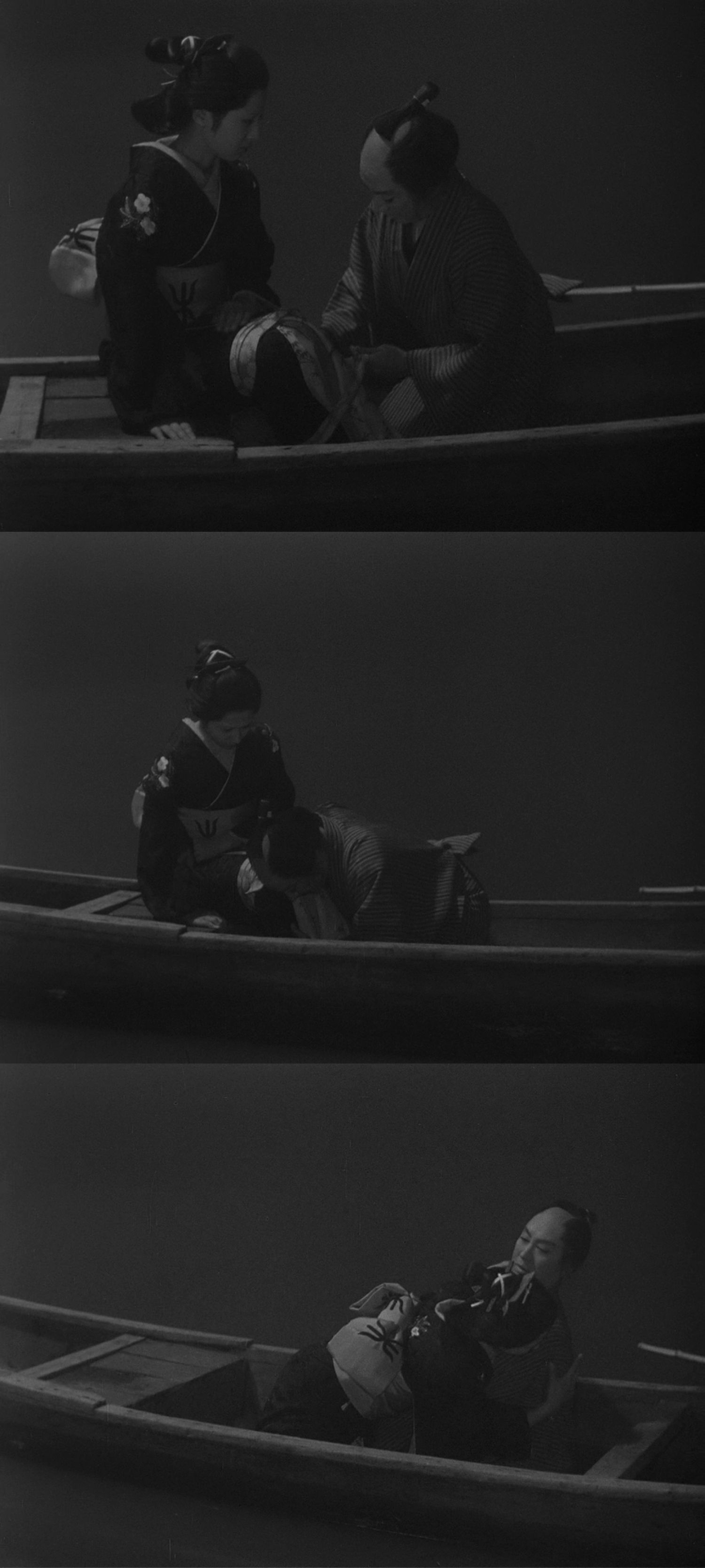

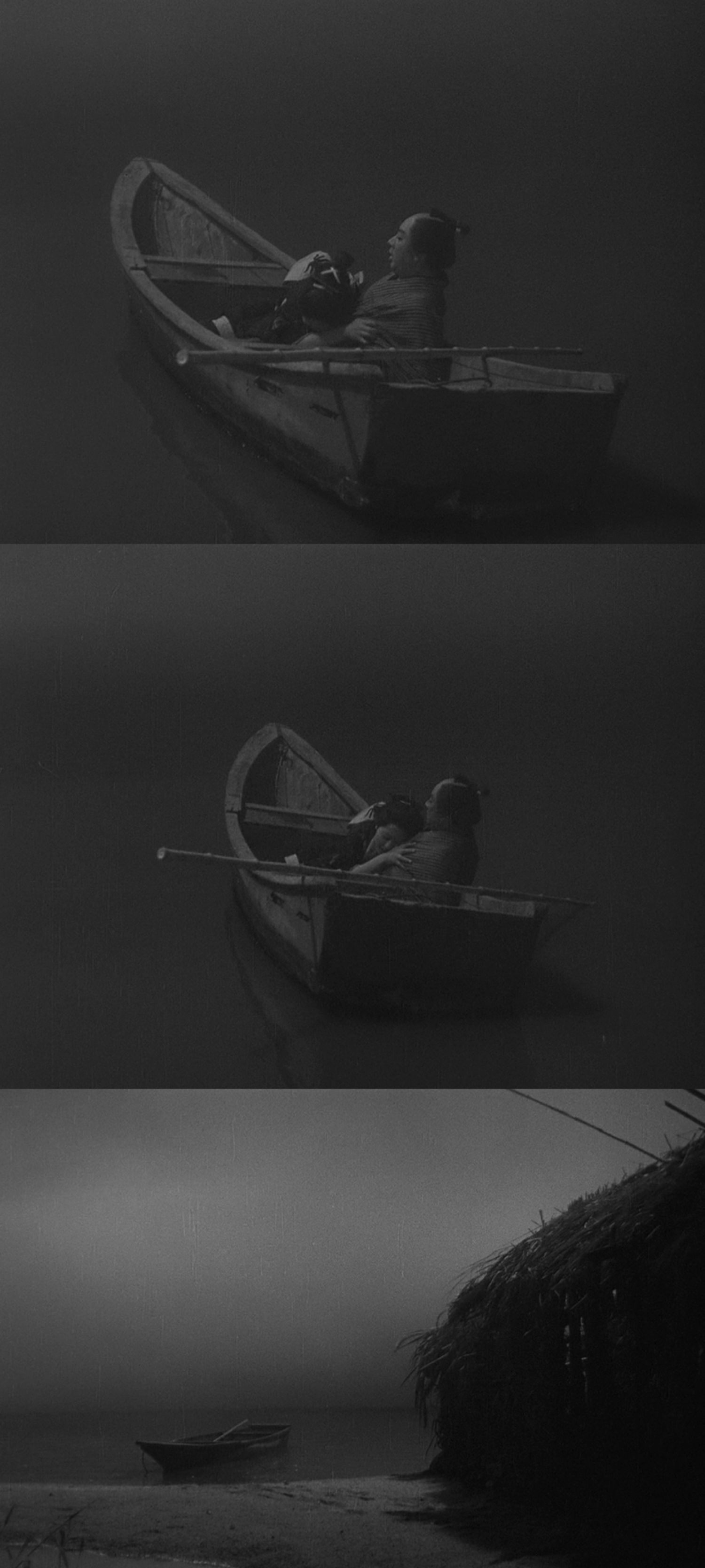

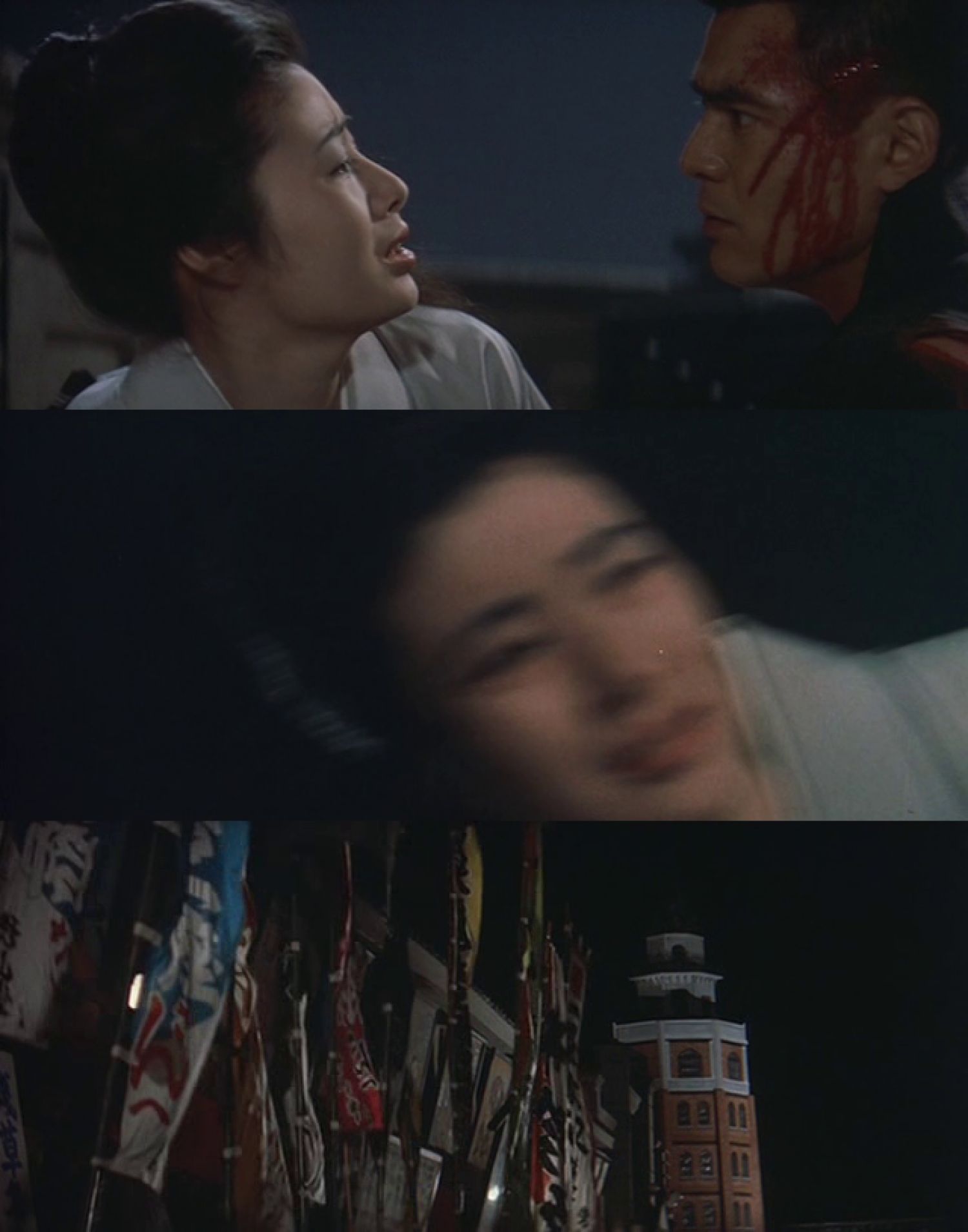

In the Red Peony Gambler franchise, Junko Fuji is casted as Oryu, a yakuza woman who goes through several adventures and encounters many male companions that help her restore justice wherever she goes. All movies end the same way: integrity wins against the creeping and suppressed power of eros and Fuji continues roving alone from land to land. However, in the sixth chapter of the saga, Oryu Returns, Tai Kato materializes the hidden desires of the female main character, framing, in an exquisite way, phallic elements.

In their first meeting, Aoyama and Oryu barely face each other and look away to the horizon. A chimney in the left corner shows the linear geometry of Kato's framing: all scenes require a certain verticality that recalls, once again, the silent and sexual tension between the two stoic characters. When their gazes meet for the first time, another chimney (this time emitting smoke) appears in the next shot. Aoyama, not wanting to fall into temptation, avoids looking at Oryu and exits the shot from the left side. Oryu observes him expectantly while the sound of the boat motors display the heartbeats of her anxiety.

At the end, after the formulaic massacre of the villains that unites Aoyama and Oryu not in love but in violence, Kato still had the audacity to finish his film with another last phallic symbol.

Aoyama abandons Oryu after having helped her defeat the bandits. Her reaction of agony and rejection is paralyzed with a freeze-frame and it's followed by the last shot, a standing tower, which totally contradicts the melodramatic aspect of the scene. Kato, then, uses phallic symbols as a last visual remnant of fleshly desires in a state of perpetual self-censorship and chastity. For the Saints, sexuality can only be experienced through symbols, dreams or hallucinations.

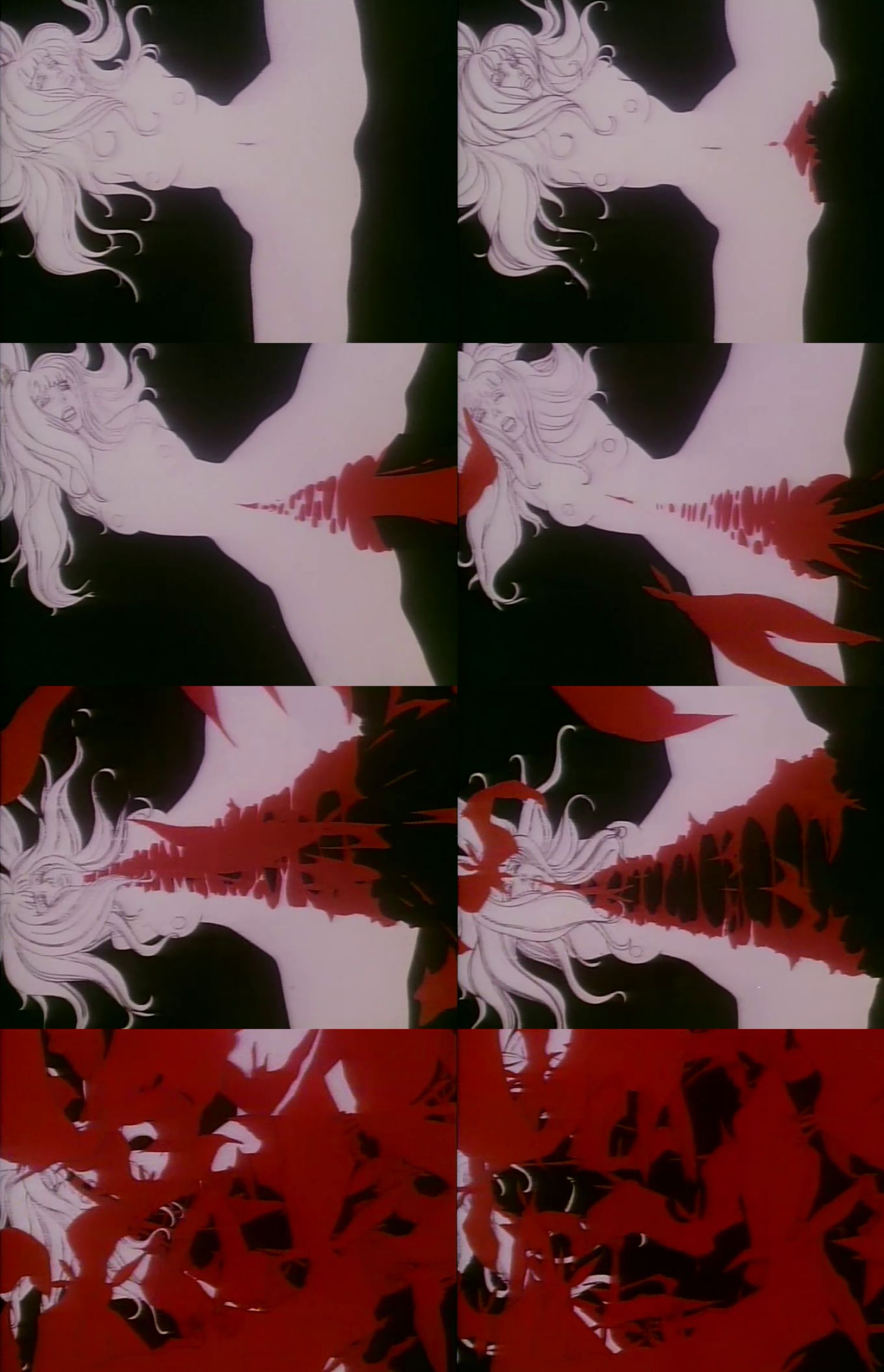

2. Belladonna of Sadness: the perversion of the non-explicit

To paraphrase James R. Alexander article «Obscenity, Pornography, and the Law in Japan»: «In Japanese law obscenity is defined in terms of the explicitness of visual images rather than anticipations of aberrant behavioral consequences.»

This means that the censorship praxis that comes from article 175 of the Japanese Penal Code easily, and in the course of the decades, is more related to a formal aspect rather than a content one. In the avant-garde animation feature film Belladonna of Sadness, the cruelty and perversity of the images are totally liberated from the explicit nature of the sexual organ in order to outline a perhaps more sensual, terrifying and obscene feeling than if it were really represented. And yet, the law didn't find it obscene. Much more concerned with live-action images than metaphorical transfigurations and pictorial alchemies, the censors inadvertently allowed the survival and revitalization of perversity by means of what is explicit in the non-explicit.

In the scene where Jeanne is brutally raped by the King and his footmen the will of the prudish legislator is made: there are no shocking genitals and even the character's vagina is nothing but a pale insignificance, erased by the censor's rubber owned by Eiichi Yamamoto, the director himself. But the graphic disruption of the body (which corresponds to the chromatic contrast between the red and the white of the rape) lets us feel, without clearly perceiving, the forced opening of the female organ and the penetration that annihilates, literally, the life of the woman who gushes blood bats.

Taking the non-explicit to its explicit limits, but denying genital depiction, considered obscene by law, Yamamoto in the wake of his master Osamu Tezuka introduces in animation (in art) a privileged place where the potential for expression and metaphorical construction is beyond any legal constraint of obscenity.

3. Tatsumi Kumashiro and the provocative way of censorship

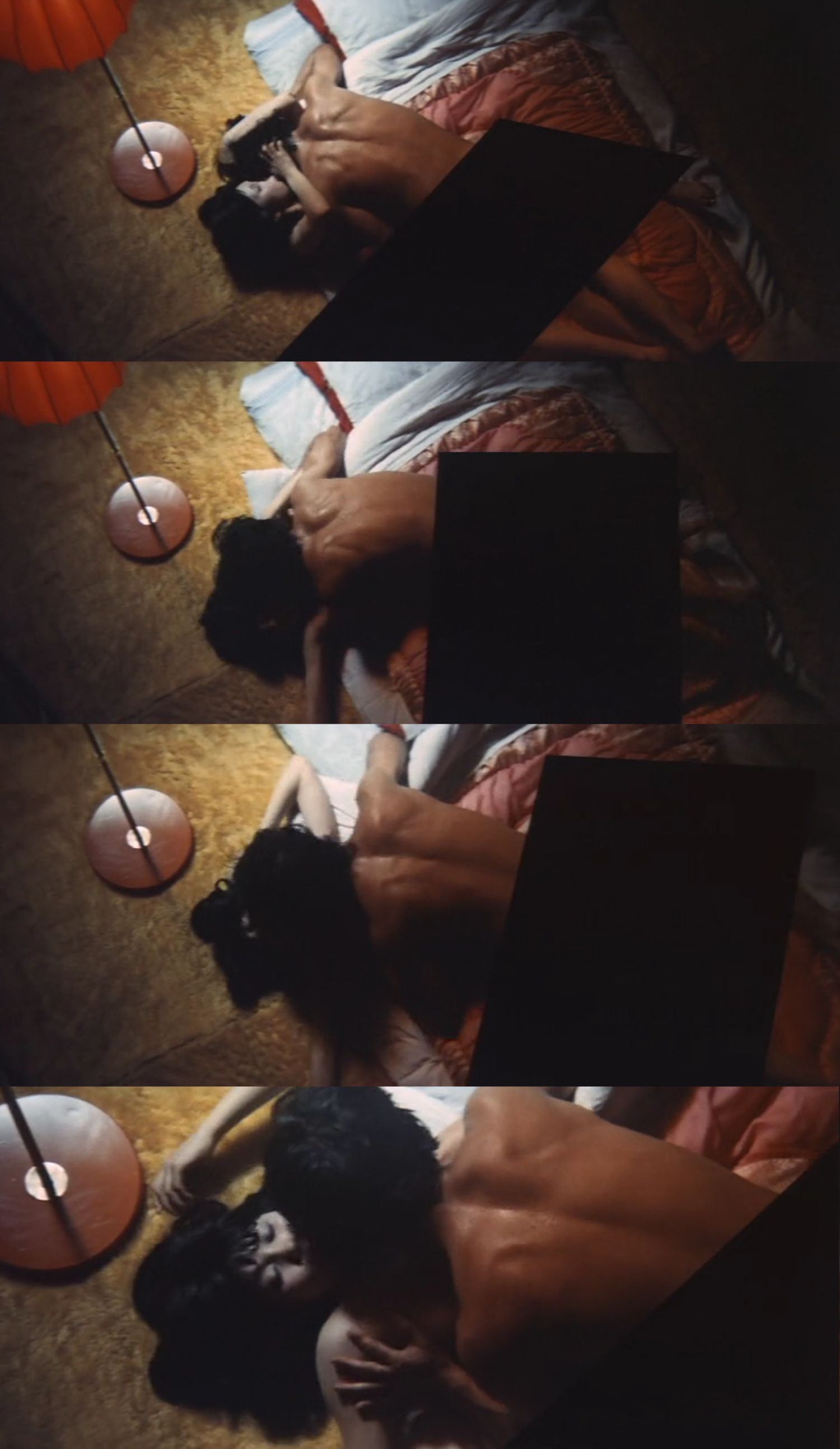

During the 70's and faced with the popularity of exploitation, the Japanese film industry was forced to democratize censorship bars: be it blurred mosaics, black bars or even mild blackouts in the film. This seemed to condition the subliminal capacity of certain images, since the explicitness was now merely hidden. Tatsumi Kumashiro’s iconoclasm, a director unfortunately forgotten who dedicated his whole life making erotic films for Nikkatsu, was the polar opposite of Yamamoto’s, even though their disapproval of censorship was common to both. One took advantage of animation to transgress censorship, the other censored excessively.

As we can see in Yakuza Goddess - Lust and Honor, the black bar, much more extensive than usual, has a life of its own and even accompanies the movement of the two lovers in bed.

In another case, he censors what wouldn't be necessary to censor, because the body of the protagonist clearly covers the genitals of the characters filmed. The two censorship bars still remain between the couple, not censoring anything relevant.

In true provocative fashion, Kumashiro displays the black bar as a phallus that tears the image apart.

What is the reason behind the censorship overload on Kumashiro's filmography? Firstly, it seems to serve merely as a parody of the regulations that the directors of erotic films had to comply in order to view their films commercially distributed. In this sense, the concealment is subversive because it laughs at itself, exaggerating the system's rules and the law, but it also works on another level: it denounces the ambiguous activity of the censor. The black bars associate the processes of hiding to obscene content. When he censors, sometimes at random, other times with a clearly symbolic meaning, Kumashiro intends to put theviewer in an indiscernible zone where he is forced to question the meaning of censorship, its implied visuality behind the black bars. But there’s more: he subverts the gaze, making us fall into a deadlock between legally censored content and content without nexus, created by itself on a whim. Finally, he aims to clear the issue of censorship, to equalize the legal with the absurd dimension, and underline this simple fact: obscenity is in the eye of the beholder and therefore its statal control is nothing more than a joke.