Solar myth to live by. Fukuko Ando and Amaterasu

Katherine Sirois

天照 – Amaterasu: the performance

The name of this solar goddess, one of the central figures of ancient and modern Shintoism, sets the tone for the artistic performance designed and staged by the Japanese stylist Fukuko Ando. This exclusive show took place in Lisbon on the 19th and 20th of June 2015. Interpreted by the French dancer Solène de Cock and set to music by the Mexican composer Jorge Govea, the performance merges genres, media, spaces and times. At the crossroads of the most remote ancestral traditions and of contemporary experimental creativity, Fukuko Ando brings together, in an unconventional way, haute couture and dance, butō, theatre and trance, initiatory mysticism and world music.

Intentionally fixed at the summer solstice, the time of the year when solar illumination is at its longest, the syncretic performance aimed, like a former ritual (matsuri), to celebrate Amaterasu, the sun-goddess[1]. The performance was integrated in the temporary exhibition of selected pieces produced by the stylist in the Museum of Decorative Arts of the Ricardo Espírito Santo Silva Foundation (from the 3rd of June to the 3rd of August 2015). In the ancient decorative art museum’s rooms and on the podium of the central hall, the visitors could discover the creations with evocative titles, Union (white silk organza, 2014), The New Alchemy (white chiffon, red, violet, black silk satin, lace and trim variations, gold and silver threads, Swarovski crystal, 2008), Water (blue silk chiffon, 2005), Sound Galaxy (Swarovski crystal, metallic gold thread, 2007) and Wing of Light, two creations from 2007 (red silk and blue silk).

The «ceremony» began at Largo das Portas do Sol at the rhythm of church bells, so familiar in Portugal and France, where Fukuko Ando settled for nearly three decades. Entirely enveloped in a pure black silk chrysalis, a figure solemnly climbs the grand staircase that leads to the noble hall. The pace is slow. The silence breaks through the beating of the bells. Like a funeral procession, the spectators follow the heavy march step by step. A slow, deep, difficult breathing is heard. The figure seems to come out of the land of the dead. Curved, tense, closed, opaque and sinister, the gestures and the expressions, together with the sound atmosphere, contribute to spread a sense of pathos. The dancer’s movements are constrained and erratic.

Then, marking a sudden transition, the electronic hang drum harmony, produced live by Jorge Govea, resounds for the public’s relief and enchantment. Without a loss of tension and intensity, something bright is gradually taking hold. The rhythm remains rather slow, punctuated with hypnotic sounds. After a noticeable slowdown, the time of the hang accelerates in a fresh and invigorating cadence. From shaking to shaking, the character, in a state of crisis, gradually enters into a hypnotic trance, which we suspect to be purifying, transforming and liberating. Thanks to the dancer’s increasingly marked and free movements, the black chrysalis unfolds to reveal a sparkling and luminous silk sunshine dress, signed FA. The rite passage symbolism is clear. We gradually move from the suffocating realm of the dead, from heaviness, suffering and psychic confinement to awakening, rebirth, to an inner opening and to a progressive manifestation of a spacious joy, as defined by Jean-Louis Chrétien in his essay on dilatation[2]. The acme of the crisis to which the paroxysm of the dark state of mind leads is expressing itself through the mystic dissociative state of the trance. Without this psychic dissociation process, the illness and depression could be fatal. But instead of meeting definitive death, it gives way to a transformative experience, to the unfolding of the self and to cosmic accomplishment.

Splendour and triumph of Amaterasu! We are thus witnessing the embodied spectacle of inner purification, of life vivification and of the transmutation of lead into gold. The deficient vital force gradually unfolds, begins to move, to animate with enthusiasm to achieve free flowing. It reinforces itself thanks to the sonorous and vibratory energy of music that gives shape to the material manifestation of the invisible. The striking dance and jubilant music rise together in crescendo, reaching a climax point where the character keeps hanging in her full vital power and her true glorious nature.

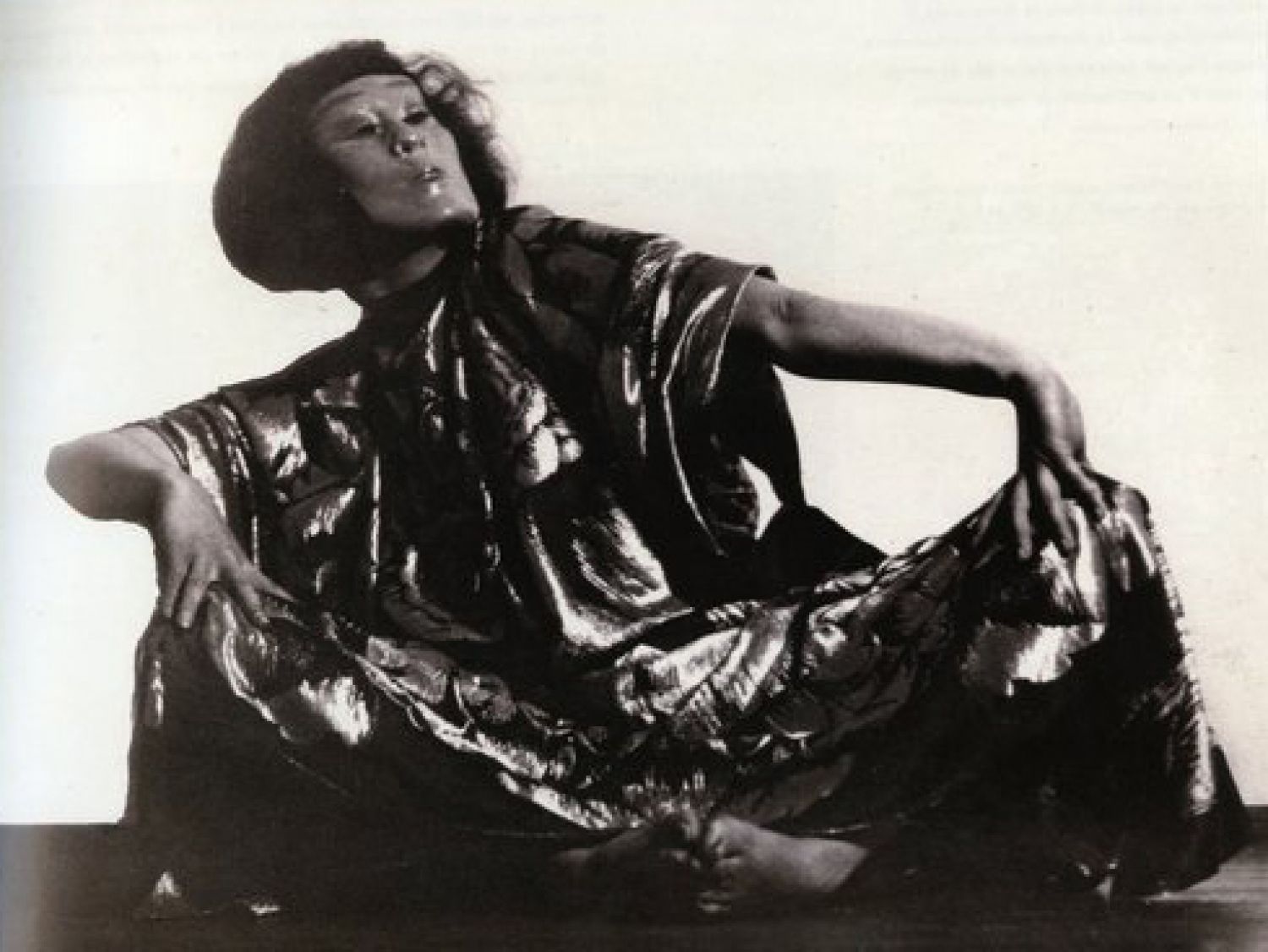

The gestures and expressions of Solène de Cock evoke, in some aspects, the modernist and expressionist Witch Dance composed and interpreted by the German pioneer Mary Wigman (1886-1973) between 1914 and 1926. Having the beats of a repetitive ecstatic raw percussion as independent background sounds, instead of the conventional repertoire music, Wigman performed a ritualised chthonian possession dance. Hence, she operated an unprecedented breach into the aesthetic notion of the beautiful in dance based on external rules and codes, on sublimation, on harmonious arrangements and attractive settings. This hitherto unseen minimalist theatrical production broke with the classical tradition of ornamental and virtuoso group choreography that follows and interprets the music according to a preexisting narrative. Such subjective commitment and self-fulfilment combined with creative, autonomous and free bodywork, as well as improvisation and solo performance were central in the avant-garde, expressionist and dada movements, which has exerted significant influence to this day in the contemporary dance field.

While Wigman gave life to the hieratic facemask she wore in Hexentanz, Solène de Cock petrifies her facial expressions into something that recalls the archaic presence and role of the mask in ancient Greek tragedy. The prosôpon, meaning all together the natural and the artificial face, was conceived as an arising power from the abode of darkness, of the invisible and the shapeless[3], an uncannily life-like object whose appearance is likely to provoke discomfort and anxiety effects. But it is above all the Japanese dramatic art of butō that underlies the bodily and facial expression of Solène de Cock. In the continuity of the butō founder, Tatsumi Hijikata (1928-1986) who had studied among other styles, the German expressionist dance as well as the French surrealism movement, Solène de Cock explores the tension between order and chaos, movement and fixity, life and death, peace and war (the annihilating catastrophe of the atomic bombings of Nagasaki and Hiroshima, the time petrifaction, the slow return, after the trauma, to a painful and deeply wounded life[4], together with the Japanese socio-political upheavals of the fifties and the sixties, are realities underlying butō corporal work and expression).

As she plunges into a state of crisis, which may be either linked to an individual or a social and collective actuality, she also goes into the realms of dream and imagination, dissonance and distortion, intermixing ugliness, deformity, pathos and absurdity. At the crossroads between the arts of mime, dance, performance and a vivid spirituality, she deeply and slowly embodies a mental and emotional universe that is at the same time minimalist, charged and poetic, a space where the most secret and vibrant interiority engenders and shapes every posture, move and facial expression. Through initiation journey and transformative trance, the character seems to probe the depths of her heart and mind, while exhaling a powerful sense of the Sacred in her way of relating to the body, the world and the cosmos. What Amaterasu the performance focuses on is not the heaviness of darkness, as if an eternal night might succeed the day[5], as Wigman famously asserted in her Journal, but on the idea that the daylight always succeeds the night, even the darkest one. In this sense, there is an optimistic standpoint in the performance that also coincides with the view expressed by Wigman in her text The Language of dance: «A thousand times I was exalted by the ‘dying and reborn’ of life [...]. To live life, to affirm life in the act of creation, to elevate and glorify it? This is what I would like to write»[6], or «what I would like to dance» would probably add Solène de Cock. But ultimately it’s the same thing as their dancing is an independent performing language. Amaterasu is not an «out of time» and «out of reach» entity, but rather a permanently regenerated current, active and benevolent one.

The feminine and Japan of ancient times

Placed under the auspices of one of the most important and delightful myths of the Shinto tradition[7], that of the divinity Amaterasu – the Great Imperial Spirit illuminating the Sky – the performance tends to evoke, thus, a mythical Japan, a world where inanimate objects (stones and rocks), natural phenomena (mountains, seas and rivers...) and living beings (men and animals) are invested with vital, supernatural and sensory forces called tama and kami. Numerous, beneficial and healthy, these vital forces were synonymous of a long, happy and luminous life. Malicious, impure and sick, they inversely dictated a mediocre, poor and deficient life, tinged with misfortune and death. Sovereigns regularly exposed themselves to purifying rituals (chinkon-sai) in order to increase and strengthen the number of good tama and to chase away the bad called tamashizume and tamafuri. The arts of dance, orality (kotodama), music and singing were all incantatory prayers (norito) and powerful tools of active and transformative magic. Women held an essential role as Japanese society was not yet subject to the rigor and austerity of triumphant patriarchy. Shamans, ascetics, healers, sacred priestesses, prophetesses, goddesses... they were recognized and celebrated both as sources of life on Earth and as beneficial for the human society. These sacred characters founded imperial lines, legitimized power, guided sovereigns both male and female, as well as they directed individuals and communities in their actions and decisions. They were at the centre of things and events both horizontally and vertically[8]. And of course, to have, as the supreme power in the sky and on earth, a female character is not familiar in our modern three monotheistic faiths despite the fact that it seems to be a surviving image and personification of ancient political, religious and spiritual matriarchy.

«The motive of the sun as a goddess, instead of as a god, is a rare and precious survival from the archaic, apparently once widely diffused, mythological context. The great maternal divinity of South Arabia is the feminine sun, Ilat. The word in German for the sun (die Sonne) is feminine. Throughout Siberia, as well as in North America, scattered stories survive of a female sun. […] Traces remain in many lands; but only in Japan do we find the once great mythology still effective in civilization; for the Mikado is a direct descendant of the grandson of Amaterasu, and as ancestress of the royal house she is honoured as one of the supreme divinities of the national tradition of Shinto. In her adventures may be sensed a different world-feeling from that of the now better-known mythologies of the solar god: a certain tenderness toward the lovely gift of light, a gentle gratitude for things made visible […]»[9].

Amaterasu: the mythical story

The myth of Amaterasu appears for the first time in Japanese literature at the very beginning of the eighth century. The story is told in the two major mythological compilations of Japanese culture, the Kojiki (Chronicles of Ancient Things, 712)[10] and the Nihon Shoki (Annals or Chronicles of Japan, 720)[11]. The enterprise was commissioned by the sovereigns to build an official mythic-historical narrative and to establish its authority both at the national level and in relation to the surrounding powers of China and Korea. They sought to distinguish themselves from their neighbours, despite the latters' undeniable and permanent cultural and religious influence over Japanese culture.

The Kojiki, begun under the reign of Emperor Tenmu Tenno, the fortieth Emperor of Japan who reigned from 672 to 686, was pursued under the command of the Empress Genmei (661-721). Combining mythology, history, literature and religion, it includes the cosmogonic myths, the stories of the founders of the world and of Japanese society, all related to the primordial divinities. It extends chronologically until the beginning of the seventh century AD. The Nihon Shoki was written by numerous authors, among whom Ô no Yasumaro (? -723) and Prince Toneri Shinnô (676-735), the third son of Emperor Tenmu. The book, which is also rich in relevant information on the societies of men, heroes, spirits and gods, is more focused on the chronological history of Japan and aims, more than the Kojiki, to establish official versions of the myths and legends «constituting the correct tradition»[12].

The Amaterasu direct imperial descending genealogy served the sovereigns quest for legitimacy in their exercise of power. The sun-goddess also transmitted to the emperors the official insignia of power: the sword, the mirror and the jewels constituting the Sacred Treasure in Japan[13]. The myths and rites recorded in these two classical compilations have their roots in prehistoric and proto-historic Japan, where Shintoism, an essentially animistic and shamanistic indigenous religion, manifested itself in its most rudimentary form. «From a spiritual point of view, the people of Jômon (a cultural period which corresponds approximately to the Neolithic period, and which precedes the Yayoi and Kofun periods) belong to the group of traditional religions’ practising, a way of thinking and depicting for which the «Sacred» is omnipresent, latent and potentially immanent in all living animal, plant, human, natural and celestial environments. This sacred essence can manifest itself at any moment and in every possible form. The «Sacred» is a creative force of life in its manifestations, but seems to be venerated to be Life itself, elevated to the rank of «Central Mystery»[14].

The two great compilations of the 8th century gathered thousands of narratives from the oral tradition, poems, songs, millenary beliefs and portraits of the spirits (tama) and divinities (kami), giving them a logical and chronological form that was at the same time artificial and influenced by the pre-existing Chinese models. It was also during this period that the cult of the sun, previously linked to abundance, fertility and indigenous agrarian rituals, was institutionalized by Emperor Tenmu. The imperial Family (Yamoto court) quickly monopolized the myth. In 1868, Shintoism became an official state religion in order to serve expansionist aims and nationalist ideology under the Meiji Restoration (1868-1912). From this point of view, attempts were made to «purify» the official Shintoism of its foreign components, in particular of the elements explicitly derived from Buddhism[15].

The myth of the Shinto tradition relates that Amaterasu, the solar goddess and beneficent priestess who reigns over the kingdoms of Heaven and Earth in the «middle country of the reed plain», angered and wounded by the sacrilegious acts and destructive behaviour of her brother Susanowo no Mikoto who competed for the usurpation of his sister’s rights and power had withdrawn into a cave, sometimes interpreted as the equivalent of the grave[16]. An eternal night fell on the world of men. The spirits and divinities, coadjutors of the goddess, united in order to avert the disturbing permanent and fatal «eclipse» of the Sun. They undertook an incantatory ritual and used all together extremely powerful means as magical talismans, incantatory formulas and operative prayers. Then the ancestral goddess of the witches and shamans (miko), Ame no Uzume no mikoto, executed a frantic and ecstatic dance in front of the «celestial dwelling-of-rocks», which operated the desired effect on the goddess. The latter, attracted by the cadence of sounds, movements and songs, but also by the audacity of the priestess who denuded herself and who, by this gesture, aroused a strong reaction of rejoicing among the assembly of the kami[17], moved the great rock which blocked the den and emerged from her retreat. Coming out to the celestial society, Amaterasu found herself dazzled by the brightness of her pure luminous splendour, for the kami had hung on the branches of a tree of evergreen foliage, multiple mirrors conceived as so many solar attributes. At once subdued and amused, Amaterasu, seized by the god Ame-no-ta-jikara-wo-kami (god-with-the-powerful-celestial-hand), was then healed from her suffering and affliction.

As it occurs in healing and «soul pacification» rituals (tama-shizume) practiced to recall the dying souls into their body or to restore health to the sick, the magical dance performed by the shaman achieved its goal to revive the vital forces of the goddess. The shamanic and prophylactic rites practiced in ancient Japan had the effect of maintaining life, on one hand, and of repelling illness and death, on the other. «It was also a powerful means of terrifying demons»[18]. Related to the season cycles and to vitality, the myth of the sacred dance performed by the shaman to revive Amaterasu is also viewed as a prototype of the fertility rites linked to the winter solstice. The role of the shamanistic incantation dances was central in those times when human societies were greatly concerned by getting back the indispensable benefits of a strong life-empowerment sun[19].

The sculpture and the dress: When the matter becomes spirit or when the spirit becomes outfit

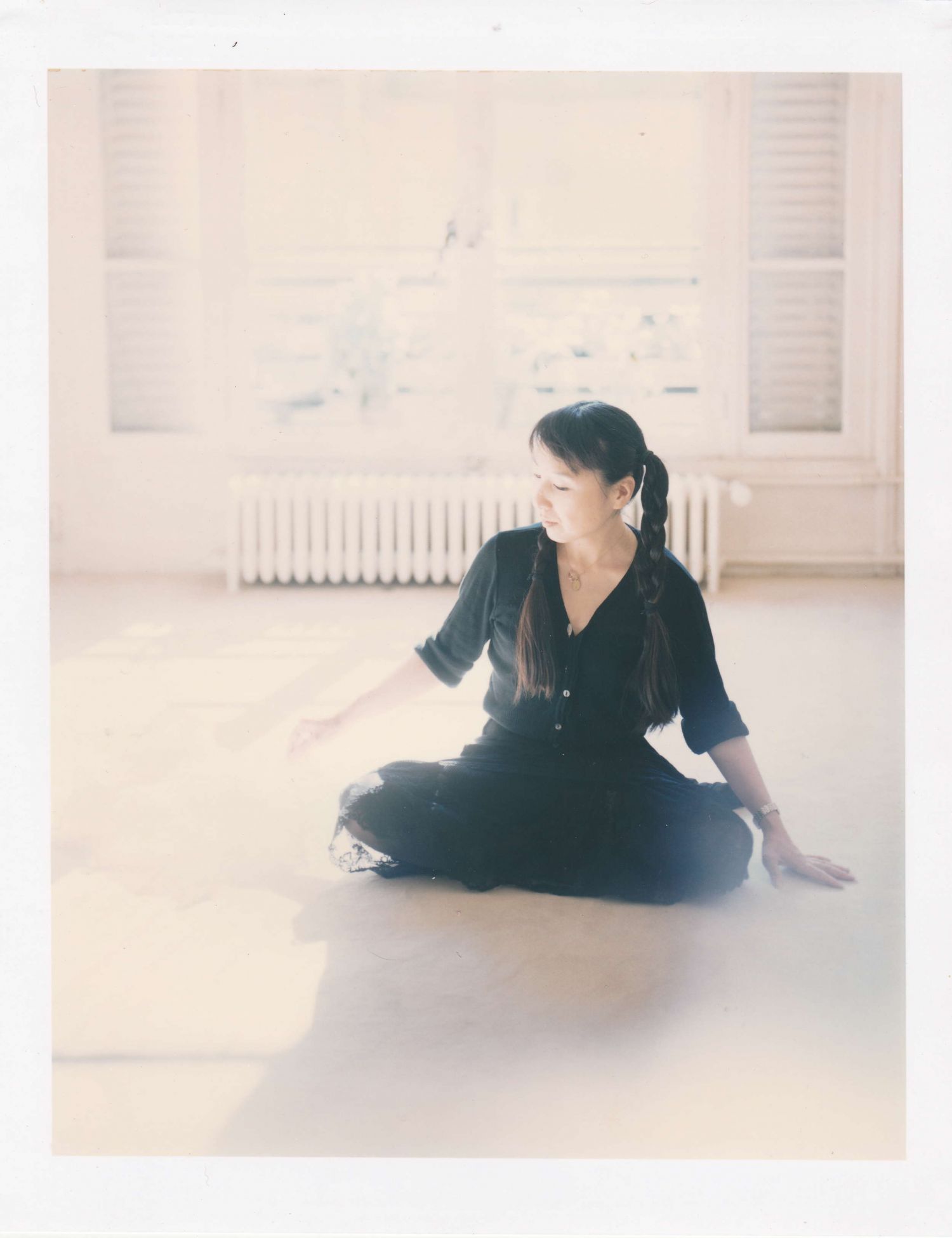

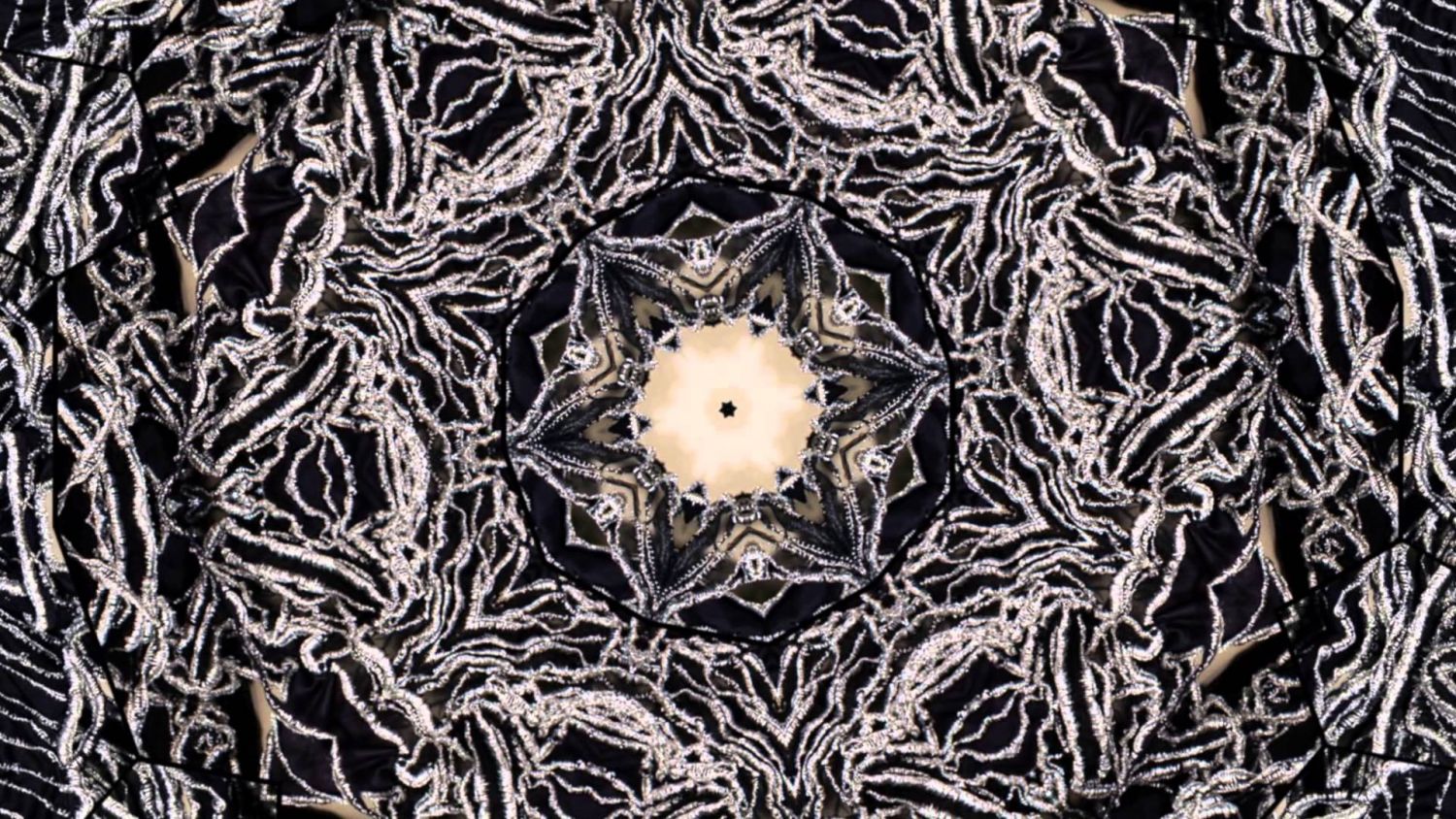

Fukuko Ando is an atypical designer on the Parisian and international stage of haute couture. The hand-made pieces she weaves herself are unique and strikingly beautiful in their sense of vivacity and complexity. Fabrics and materials, precious and varied (silk, satin, cotton, lace, organza, gold and silver thread, crystal...) are embroidered, woven, crocheted, sewn, tied by a penetrating and spiritual approach that has much to do with a certain form of philosophical and alchemical mysticism. Fukuko Ando enters, in fact, into a state of intimate communication with the matter she shapes in its most subtle, tiny, indefinable aspect. With a consciousness at once vast and penetrating, she probes the infinitely small and scrutinizes the infinitely large. Her kaleidoscopic sensibility travels through the fibre of the fabric as she establishes a dialogue at the cellular, atomic and vibratory level, where everything is pure rhythm and light. For matter, she states, has its own spirit and vital force, its tama. Because it’s pure energy, matter lives and breathes, hence its cosmic nature.

Fukuko Ando's approach consists not in drawing first, in shaping materials according to predetermined intentions, but rather in the spontaneous pleasure of sculpting the fibres directly on mannequin, letting the spirit of each fabric express during the process and through her creations. Thus, the work consists of a perfect balance between passive reception and action, implementation and orientation. Her approach seems to pass through the successive and simultaneous stages of self-abandonment, deep connection and constant transformation. She explores the invisible and energetic dimensions in their play of shadows and shimmering lights in order to capture their quintessence and to manifest it visually in new forms, colours and textures to wear.

The exhibits on mannequin invite us to contemplation in movement, which resonates with the impression of continuous metamorphosis that emerges from her works. The fluidity of her creative imagination manifests itself in the volutes, irregular curves and organic geometry, but also in the dynamic of the rays, veins and oblique lines, in the asymmetrical reliefs, elongated or truncated planes, recessed and protruding volumetry, in the sets of reflections, in the transparencies, opacities and openings. As they do not have any established front-rear sides, the dresses and the bustier develop according to a certain practice of the heterogeneous, leading to a constantly renewed differentiation and recognition.

This aspect of her work can be a transposition or a reminiscence of the esoteric art of traditional Japanese zen gardens (nihon teien) which compose so many landscape elements (mountains, lakes, valleys, paths...) in a reduced space. This art is related to the technique known as «live capture» (ikedori or shakkei). Like the garden, the fluid, composite and three-dimensional clothing is doubly inhabited. It generates an intermediate space, abolishing the boundaries between the interior and the exterior according to a vibratory emotional and aesthetic experience that combines both the impulses of integration (inward movement) and projection (outward movement). When one looks closely at it, one can feel the poetic vibration of the pieces, which will then merge with the moving body.

Resonance, energy and transmutation are key words to address the work of Fukuko Ando who has, for a long time already, shaped the philosopher's stone with which she has pierced her own ego, for the light to burst forth and for the invisible to manifest. Through her wearable and danceable poems, she explores the secret magic of living matter with which she re-enchants the haute couture, intertwining being and appearing.

Footnotes

- ^ «The word ‘Amaterasu’ is the honorific form of ‘amateru’, which means ‘shining in heaven’». Takeshi, Matsumae. (1977). «Origin and Growth of the Worship of Amaterasu». Lecture at Indiana University, Bloomington.

- ^ CHRÉTIEN, Jean-Louis. (2007). La Joie spacieuse. Essai sur la dilatation. Paris: Les Editions de Minuit.

- ^ FRONTISI-DUCROUX, Françoise. (1995). Du masque au visage. Aspects de l’identité en Grèce ancienne, Paris : Flammarion, p. 60.

- ^ Cf. TOMATSU, Shomei. (1966). Nagasaki 11:02, Tokyo, Japan.

- ^ One of the central issues of the myth, as we will see.

- ^ «Mille fois j’ai été exaltée par le ‘mourir et renaître’ de la vie […]. Vivre la vie, affirmer la vie dans l’acte de création, l’élever et la glorifier? C’est cela que je voudrais écrire».WIGMAN, Mary. (1990). Le Langage et la danse, trad. de l’allemand par J. Robinson. Paris: Chiron, p. 13.

- ^ «What is commonly referred to as ‘shintô’ includes all the religious beliefs and practices that prevailed in Japan before the introduction of Buddhism – officially adopted in the sixth century – and then, at the beginning of the Heian period (794-1192), mingled with the new religion of Buddhism; in this form they survived the Middle Ages and Modern times up to the Meiji period (1868-1912). [...] Shinto, or ‘the way of the kami’, was created in the sixth century to distinguish the ancient beliefs of the new religion that was the butsu-dô». Rotermund, Hartmut O. (1970). «Les croyances du Japon antique». Histoire des religions. Encyclopédie de la Pleiade. Paris, nrf: 958-991. Cf. CAMPBELL, Joseph. (1973 [1949]). The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Princeton University Press, p. 210.

- ^ MACE, François. (1981). «Au-delà. Les conceptions japonaises». In Dictionnaire des mythologies et des religions des sociétés traditionnelles et du monde antique. Paris: Flammarion, I, pp. 107-111; ROTERMUND, Harmut. (1981). «Esprit vital, âme. Au Japon». In Dictionnaire des mythologies et des religions des sociétés traditionnelles et du monde antique. Paris: Flammarion, I, pp. 376-379.

- ^ CAMPBELL, Joseph. (1973). «Rescue from without», op. cit. pp. 211-213.

- ^ CHAMBERLAIN, Basil Hall. (1982). The Kojiki. Records of Ancient Matters. Tôkyô: Charles E. Tuttle Company.

- ^ ASTON, William George. (1972). Nihongi, Chronicles of Japan from the earliest to A.D. 697. Vermont and Tôkyô: Charles E. Tuttle Company.

- ^ Rotermund, Hartmut. (1970). Op. cit., p. 961.

- ^ Emblems of the State Shintoism (cult of the imperial family whose power emanates from the divine), the mirror, the sword (katana) and the jewels, as they are the visible manifestation of the sovereigns’ affiliation to Amaterasu and the symbols of power and supreme authority on earth, are systematically present in Japanese Shinto temples.

- ^ VALAT, Rémy. (2012). «Le mythe de la création japonais et l’archéologie: À la (re) découverte de la période Jômon». Les mythes et les Religions. [http://www.mythes-religions.com/2012/11/09/le-mythe-de-la-creation-japonais-et-l%E2%80%99archeologie-a-la-redecouverte-de-la-periode-jomon-16-500-ans-bp-900-ans-bp/].

- ^ Cf. TAKESHI, Matsumae. (1977). «Origin and Growth of the Worship of Amaterasu». Lecture at Indiana University, Bloomington. https://nirc.nanzan-u.ac.jp/nfile/1069. NAKAMURA, Motomochi Kyoko. (1983). «The significance of Amaterasu in Japanese Religious History». The Book of the Goddess, past and present, edited by Carl Olsen. New York: The Crossroad Publishing Company.

- ^ God of storm and lightning, Susanoo, which seems to mean «violent man», is also called Take-haya-susano, where take means «strong» and haya «fast». He incarnates the physical and brutal force, of which the storm is the cosmic correspondent. Irritable, dazzling and excessive, Susanoo ravages the rice fields of Amaterasu, removes paths and roads, fills the canals and commits a whole series of misdeeds and outrages against her sister. One day, he skinned a living horse and hurled it from the top of the roof into the «pure and sacred weaving house» where Amaterasu was weaving divine garments with her spinners. One of them was injured to death. This is the event that pushes Amaterasu to take refuge into the celestial cave and, therefore, to no longer dispense her benefits on Earth and men. Yoshida, Atsuhiko. (1962). «La mythologie japonaise. Essai d’interprétation structurale». Revue d’histoire des religions, 161, 1, pp. 25-44.

- ^ This episode is reminiscent of the mythical gesture of Demeter, the Olympic goddess of the Earth and wheat cultures in Greek mythology. Demeter, afflicted with the abduction of her daughter Persephone by Hades, abdicated from her divine functions and wandered without drinking or eating under the features of an old woman. «Her exile made the land barren, and the order of the world was subverted», GRIMAL, Pierre. (1951). Dictionnaire de mythologie grecque, p. 120. But Demeter’s spirit of mind suddenly changed as a result of the dance performed by the gorgon Baubô who lifted her robe to exhibit her private anatomy. The liberating laughter initiated the end of Demeter’s anguish and mourning and originated her healing process. VERNANT, Jean-Pierre. (1985). «Le masque de Gorgô». La mort dans les yeux. Figures de l’Autre en Grèce ancienne. Œuvres. Paris: Seuil Opus, t. II, pp. 1575-1596. OLENDER, Maurice. (1985). «Aspects de Baubô». Revue de l’histoire des religions, t. 202, n° 1, pp. 3-55.

- ^ Haguenauer, M.-C.. (1930). «La danse rituelle dans la cérémonie du Chinkonsai». Journal asiatique: recueil de mémoires, d’extraits et de notices relatifs à l’histoire, à la philosophie, aux sciences, à la littérature et aux langues des peuples orientaux. Paris: Société asiatique, 216, p. 349.

- ^ «The feet are tapped to bury the forces of evil into the ground and awaken the vital forces that are hidden in the earth. Thus, this entry into trance revivifying the supernatural spirits whose strength is exhausted in the course of time. Similarly, Matsuri’s function is to increase the power of the divinity through the energy generated by the ritual and thereby increase the strength of the entire community». BERTIER, Laurence. (1981). «Fêtes et rites saisonniers. Matsuri et nenchû gyôji au Japon». Dictionnaire des mythologies et des religions des sociétés traditionnelles et du monde antique. Paris: Flammarion, I, p. 414.