Siege Mentality, Biennale di Venezia: 1969/ 2019

Romas Tauras«I am writing to you in behalf [sic] of the provisional Emergency Cultural Government (ECG). This is a large body of New York based visual artists.... The objective of this group is to stop the use of artists’ work by the US Government for the purpose of lifting the image of the administration’s atrocious policies and instead to take all showings of American art abroad into the hands of the artists themselves.» So begins a letter, dated 30th May 1969, to my father from colleague and fellow artist Hans Haacke, ahead of preparations for the Venice Biennale the following year. «The formation of the ECG and the closing of the US Pavilion in Venice will be announced at a press conference in Washington in a short while.... The schools have equally become anti-war agitation centers.»

Siege mentality. There was reason to be circumspect. Back home on the Tyler School of Art campus my father as the director of printmaking had spent time in “war room” discussions with other faculty and the dean of the school. How to secure the perimeter if violence breaks out? What can be done to assure the safety of students and staff against rogue elements either in the enrolment or for that matter in law enforcement? College dossiers from the archive give a chilling premonition of the violence at Kent State a year later.

There was a real risk the Biennale would indeed be closed, as Haacke suggested. The prior year, on the opening day of the 34th Venice Biennale of 1968, art critics arrived at the Giardini della Biennale to confront a cordon of armed policemen guarding the entrance. Political activists had occupied some of the national pavilions, turning artworks to face the walls in others or shrouding them in anti-war banners. By the end of the day, the police were engaged in a crackdown against a demonstration in Piazza San Marco. ‘La Serenissima’ was anything but serene then, and there was lingering menace in its canals much as there was in the streets of cities around the world that had been rocked by protest.

I tried to visualise these scenes of bygone violence wandering around the Giardini last May. This was not easy. Superyachts were moored cheek-by-jowl with the Vaporetto stops, the air fragrant with pittosporum tree blossoms. In the lazy sun all felt well with the world.

The Biennale in 1968 was a shambles, but thanks to the activists, organizers adopted a bolder, more provocative curatorial agenda for subsequent Biennales, establishing them as forums for cultural debate. The Grand Prizes were abolished (until the Golden Lion was introduced again in 1986), and the sales office was eliminated – declaring this to be an event for art, not commerce. Art in the pavilions is still not for sale, though it’s certainly used to sell. Wandering between exhibits it felt as though the siege mentality of yesteryear had been completely eclipsed by rampant tourism and consumerism. Where protesters shrouded exhibits with protest banners in ’68, now entire churches are engulfed in advertising-clad scaffolding. Occasionally it’s hard to distinguish art from sponsored content.

The politics is still omnipresent though, even if national agendas have given way to a globalised angst. Politics was never going to be dissociated from this Olympiad of art. The United States's miniature Monticello, Britain’s colonial neo‐Palladian villa, Germany's stripped-classical Third Reich temple (the aforementioned Hans Haacke memorably uprooted the marble floor in 1993 for his Germania exhibit), the Soviet Union's pre‐1917 Russian Orthodox pagoda - all of them declare their historical allegiances. Whether countries have a pavilion at all has depended largely on historical accident and national prestige in the early years of the last century, a curatorial legacy of Europe’s Great Exhibitions in the 19th century. Like the Isola di Cimetero where the Venetians bury their dead (after 12 years one’s remains are transferred to a bone yard at the other end of the lagoon), for decades now the gardens have had precious little room for new pavilions. The standard-bearers of the world’s nation states have expanded into the Arsenale, a war machine-turned-exhibition hall. They now pervade the very fabric of the city, like cultural embassies from Santa Lucia train station to the outlying islands of Murano, Burano and Torcello.

Even as the influence of nation-states wanes in our crisis-afflicted day, new pavilions are still being created. Ghana, Madagascar, Malaysia and Pakistan joined the Biennale ranks this year, reflecting perhaps the current obsession with national branding as much as any rise of nationalism. International exchanges of contemporary art have been co-opted through the ages for propagandist purposes. Today they are a way of signalling a dynamic and outward-looking society, a plea on behalf of citizens to be considered as qualified members of a globalised civilisation.

The first Diaspora Pavilion at the 2017 Venice Biennale challenged the ideal of nation by featuring the work of 19 displaced artists. It found little critical resonance or popular engagement. This year’s exhibit Rothko in Lampedusa, organised by UNHCR, like the sunken Migrant Boat brought up from Mediterranean depths by Christoph Bücheland and other exhibits throughout Venice, make the point more succinctly. In 1913 Rothko escaped Czarist repression in what is today Latvia to become an American and a pioneer of Abstract Expressionism. «So among the indefinite number of today's refugees, could there be a Rothko of the 21st century?» the curators ask, taking the tiny island of Lampedusa – a key reception centre for refugees – as their rhetorical point of departure / arrival to showcase works by Ai Weiwei, Christian Boltanski and five artists from Syria, Iran, Iraq, Ivory Coast and Somalia who are refugees. My father started out like one of them.

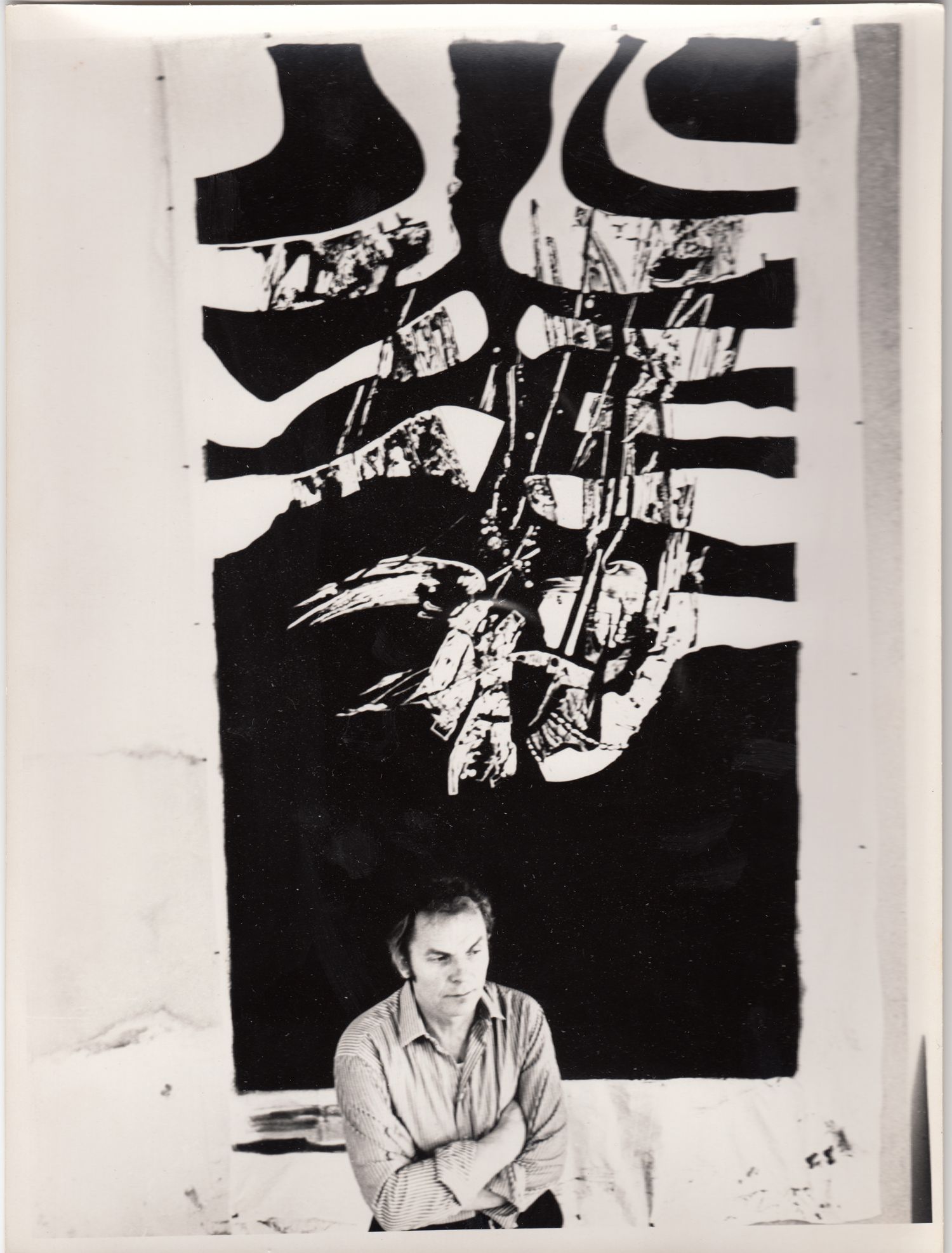

Romas Viesulas was born in 1918 in what was then Lithuania, within walking distance of Daugavpils. This city, in today’s Latvia, has for centuries been a fixed point surrounded by countries with fluctuating borders, imperial designs and migratory populations. In the early 20th century, the region was prone to oppressive Russification. During World War I and II the Eastern Front moved back and forth through it like a devastating and destructive tide. It was in this town in the Russian Pale of Settlement where Mark Rothko spent his childhood before escaping the pogroms with his family. Viesulas emigrated a generation later than Rothko to the US.

Incredibly, the modest farmhouse near Daugavpils in which Romas Viesulas was born survived two world wars and collectivisation over the last hundred years. ‘Eglaine' still stands there today, on the Latvian-Lithuanian border, basically unchanged from when he lived there as a child. And yet he never returned to this house, or family that lives there to the present day. His artistic career was framed by the experience of exile, and challenges to notions of identity. In his graphic work, he sought to universalize this personal experience through an expressionist idiom.

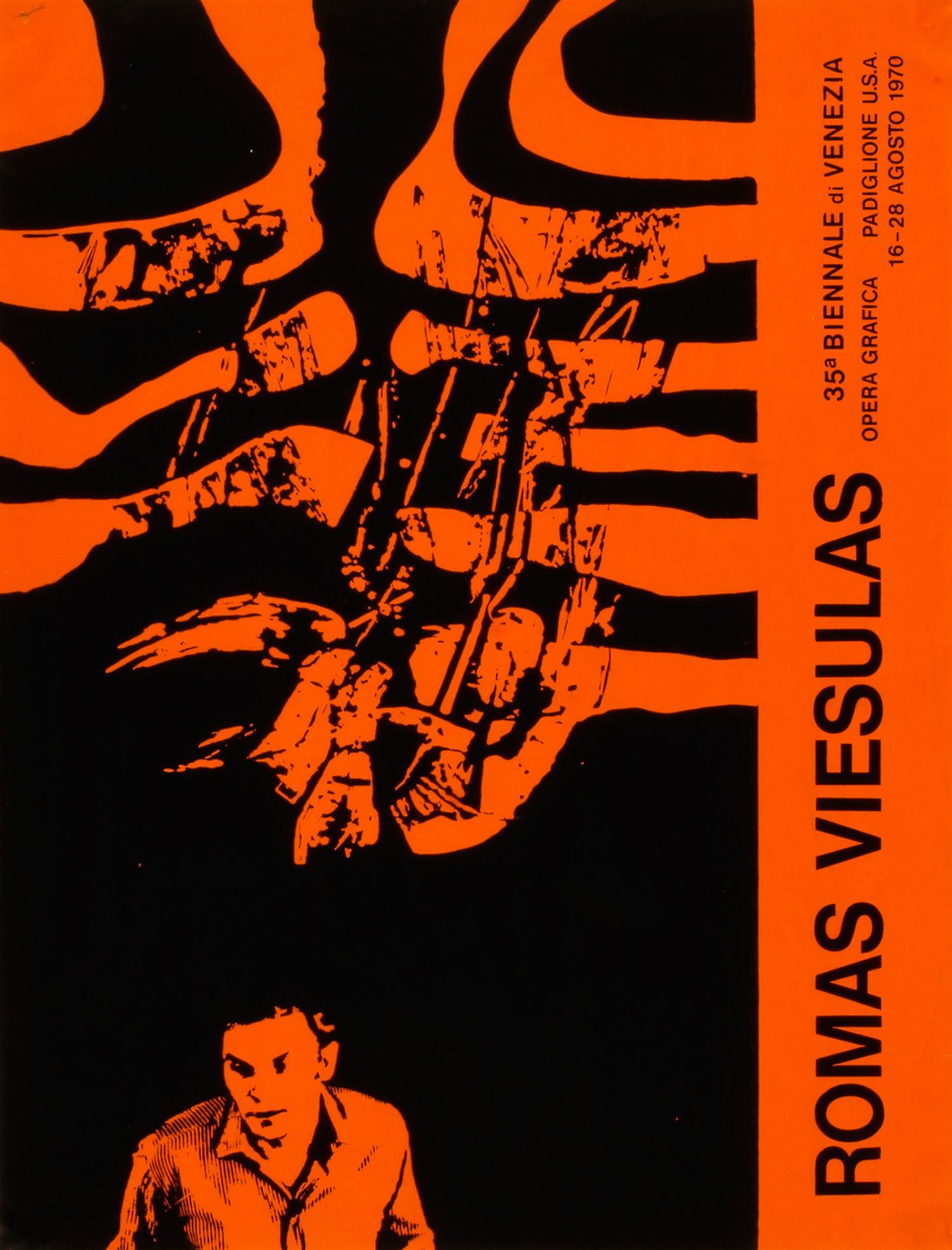

Early ambitions for a career in diplomacy were upended when the country Viesulas was training to represent ceased to exist as a diplomatic entity. Instead of a legal degree, Viesulas was ultimately awarded a ‘Diploma for Displaced Persons’ by Paris' Ecole des Beaux Arts in 1947. The fact of this school - founded and financed by the French authorities, in Freiburg after the war – seems miraculous today. It was created specifically for refugees from war. This was the unlikely academic foundation which launched his artistic career, and ultimately led him to win three Guggenheim Fellowships among numerous other awards, and to represent his adoptive United States in the 35th Biennale di Venezia in 1970, the biennial which almost never was.

«No free society should confound art with politics or with any political action which is a self-evident yet constantly confused issue.... our problems... are based in Washington and not in Venice». This was Viesulas’ response to the urgings of the ECG as they threatened to close the pavilion. Among the dropouts were Roy Lichtenstein, Robert Rauschenberg, Jim Dine, R. B. Kitaj, Claus Oldenburg, Robert Motherwell, Robert Morris, Frank Stella, Ernest Trova and Andy Warhol.

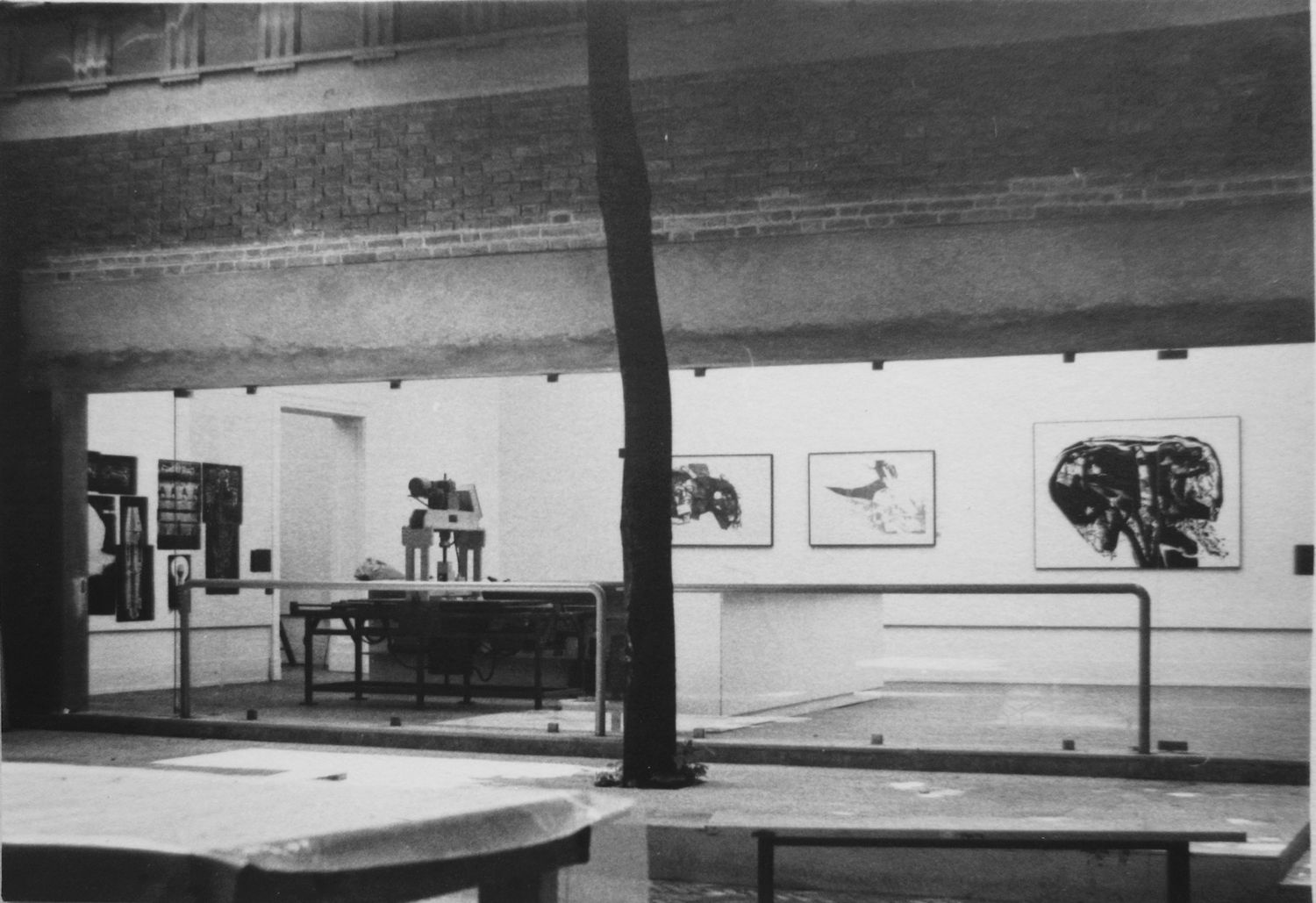

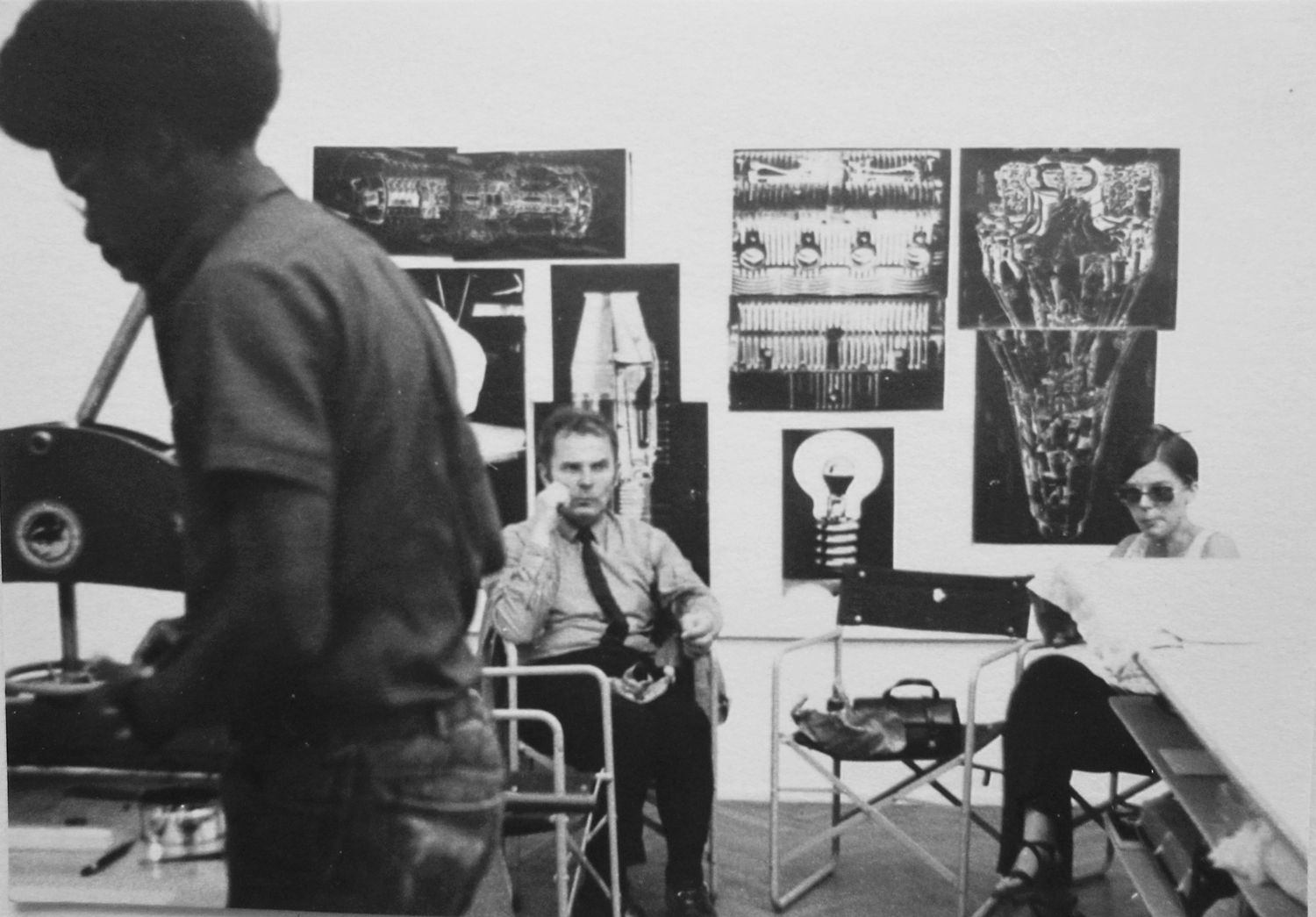

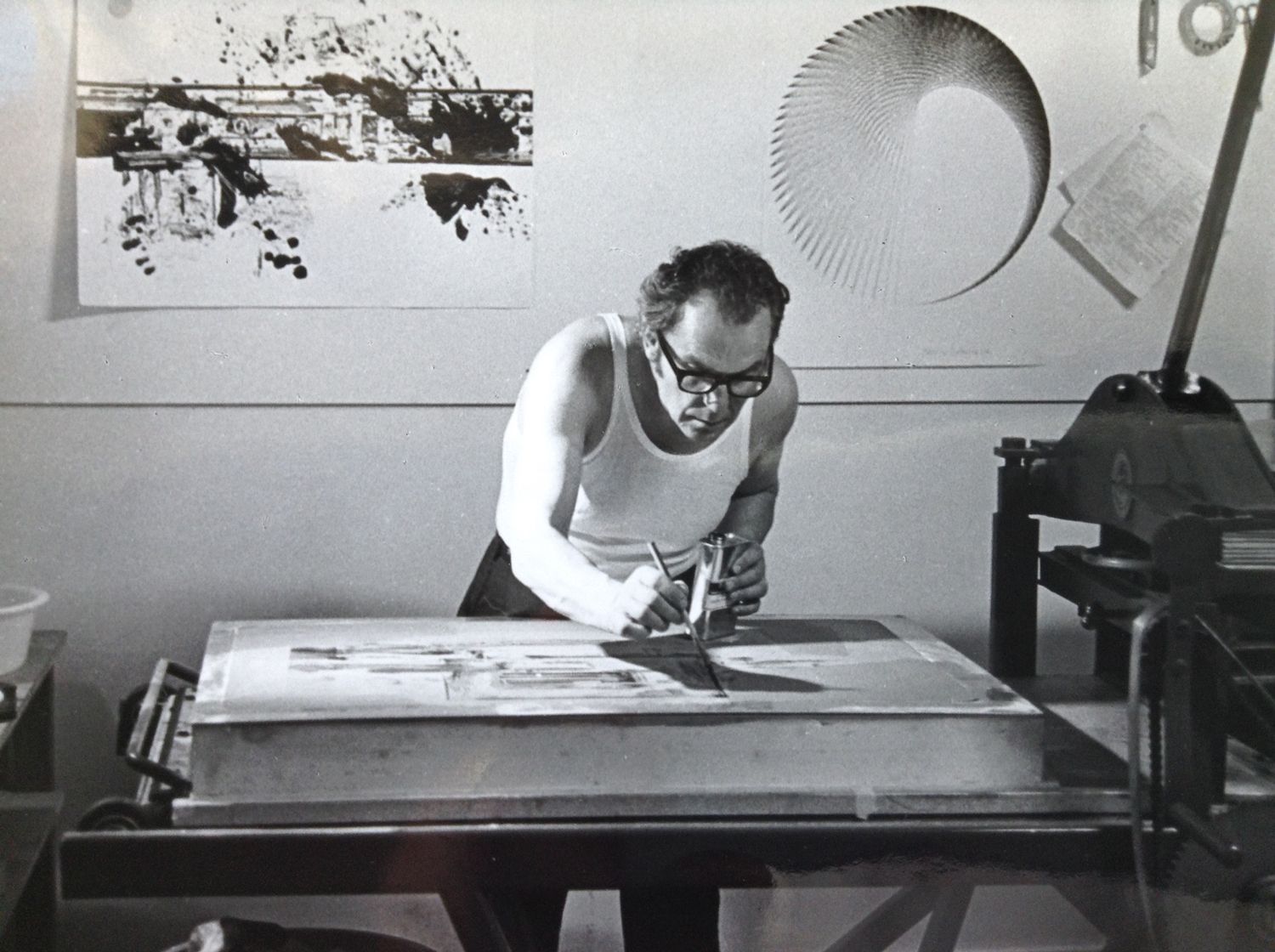

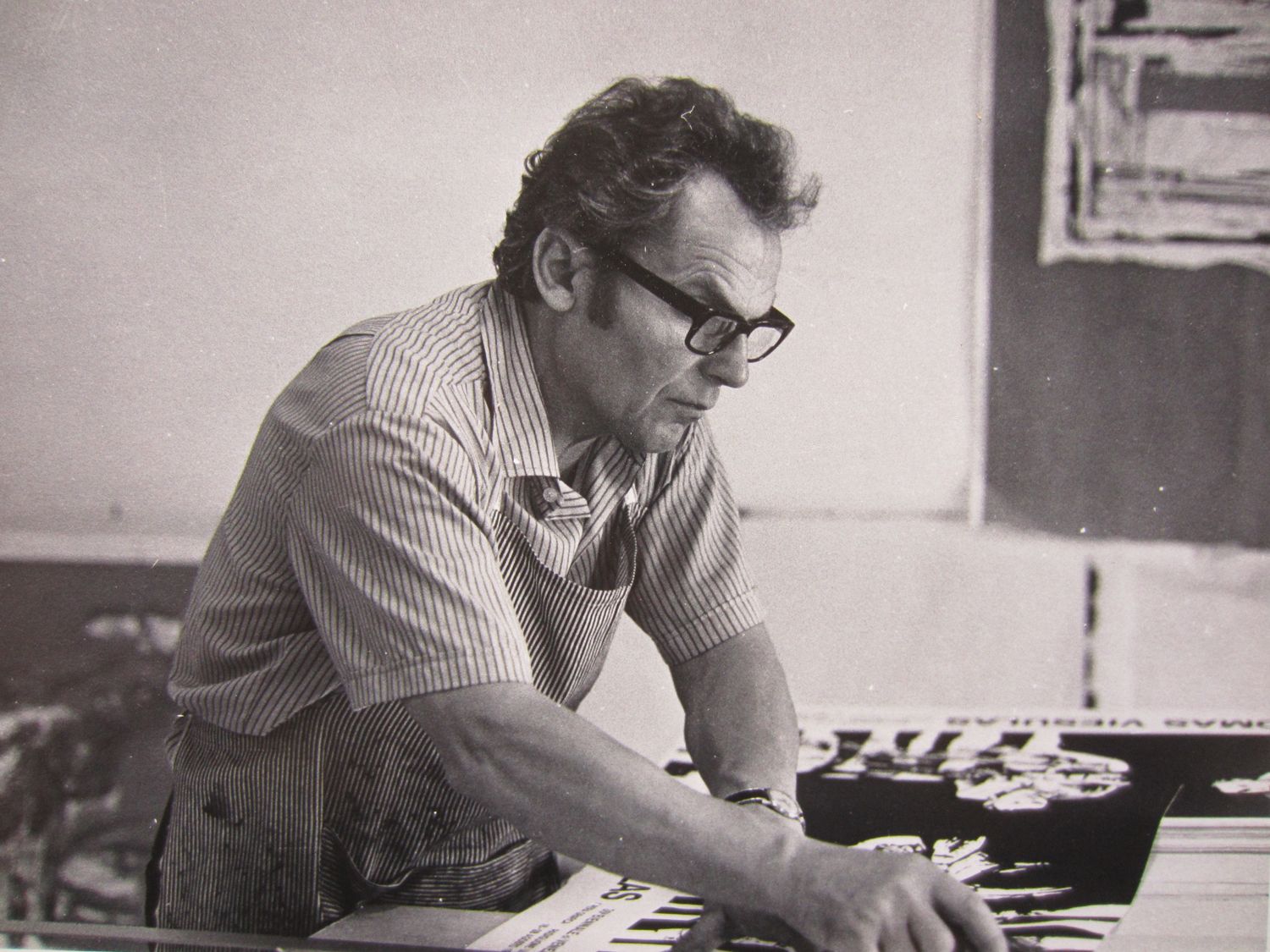

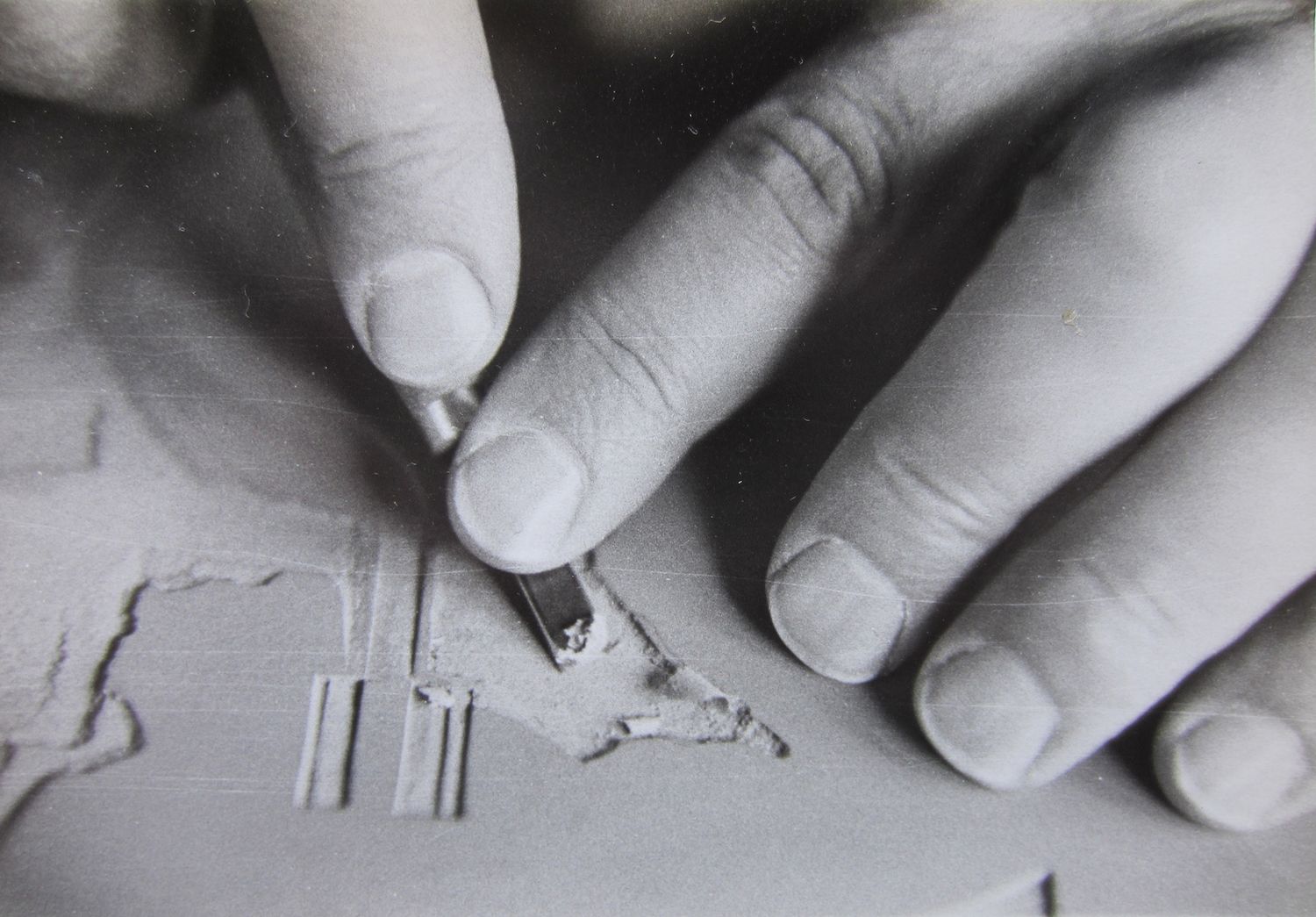

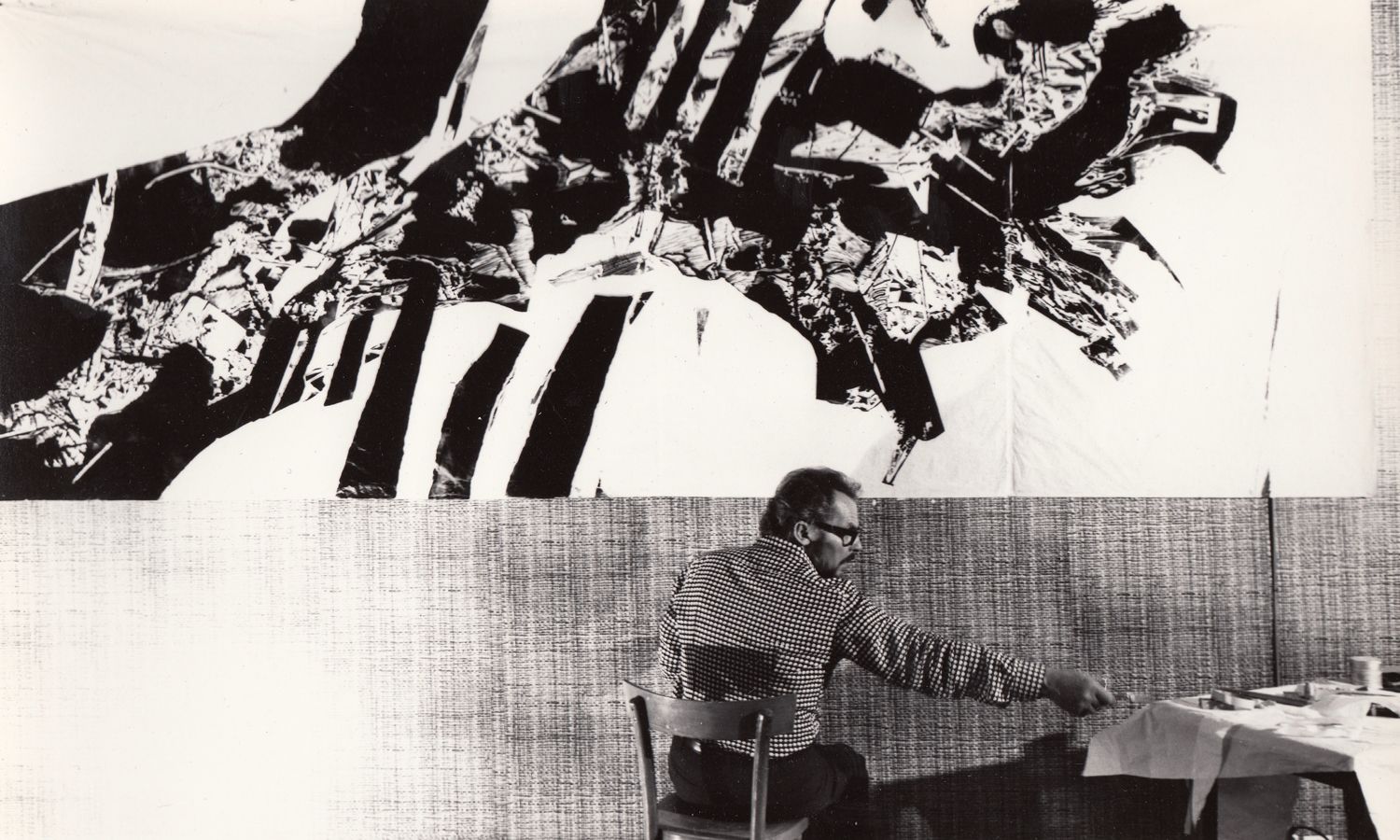

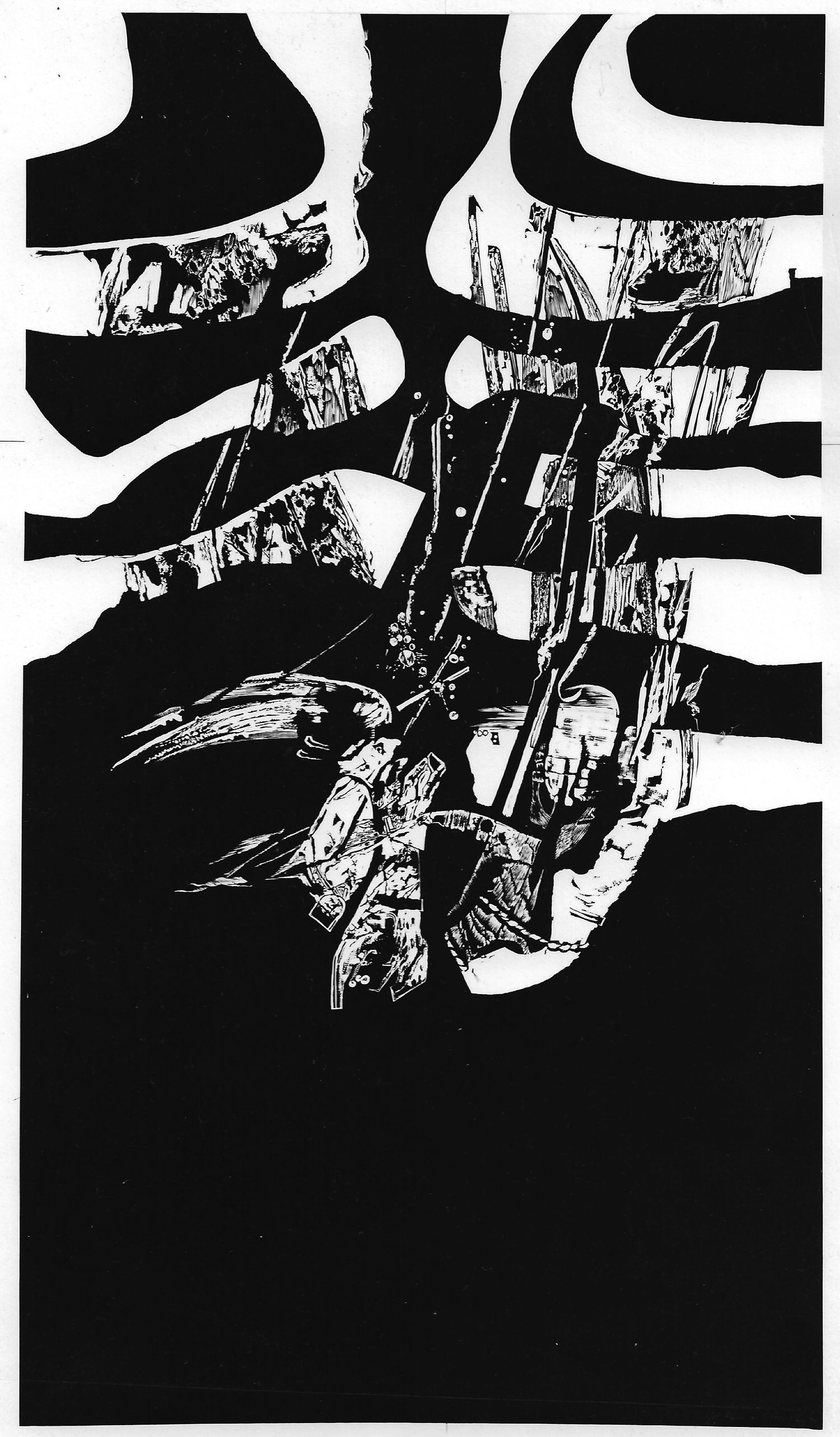

The protests of 1968 had created the conditions for a new direction, and an upending of established protocol. For the US Pavilion, this meant an «experimental workshop» giving pride of place to lithography and silkscreen printmaking. Viesulas was utterly devoted to printmaking, a champion of the underdog technique, painting’s poor relation. Others who agreed to have prints of theirs exhibited included Jasper Johns, Alexander Lieberman, Sam Francis and Edward Ruscha. Viesulas had dedicated himself to finding meaning in the medium of mass reproduction. Even if he was a stalwart for the traditional lithograph, his innovations ranged from inkless relief prints to monolithic prints on fabric, inked by hand. He had come of age artistically at a time when the arts were in thrall to the bold vision of Abstract Expressionism. Even if artistic media were fracturing and multiplying in a fascinating array of Conceptual art, Land art, Video art and Performance, he made a claim for lithography and abstraction.

However there was more than simply professional prerogative at stake in deciding to represent the United States. As an exile, he had much to acknowledge in this gesture. The Baltic States experienced their own internal displacement in the second half of the 20th century. State directives and strategies of dissent competed for the identities of their citizens, and this came to be reflected in state-sanctioned art.

He recognized the hypocrisy of the compulsory utopian visions created by artists under state sponsorship in the Soviet Union. The Soviet pavilion seemed almost like a self-parody to Western observers: busts of Lenin in miniature and a group of folk‐realist canvases — robust nude women tossing a medicine ball, robust young nude boys sporting in the water. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, exhibits toured the globe sponsored by the United States Intelligence Agency, comprised solely of prints of well-known abstract expressionist paintings, travelled to Asia, Africa, Latin America and the Middle East. In the propaganda war with the Soviet Union, this new artistic movement could be held up as proof of the creativity, the intellectual freedom, and the cultural power of the US. Russian art, strapped into the communist ideological straitjacket, could not compete. But while Socialist Realism is easy to mock with a conceptual critical eye, my father was equally suspicious not only of the most blatant state-sponsored agitprop, but also of any art that advanced a partisan agenda. He would come back to the hypocrisy of patriotic posturing in his final lithograph, Olympics (1984), which refers to a sporting event that showcased both the promise of Olympic ideals, and simultaneously the ways in which Cold War ideology eclipsed these ideals.

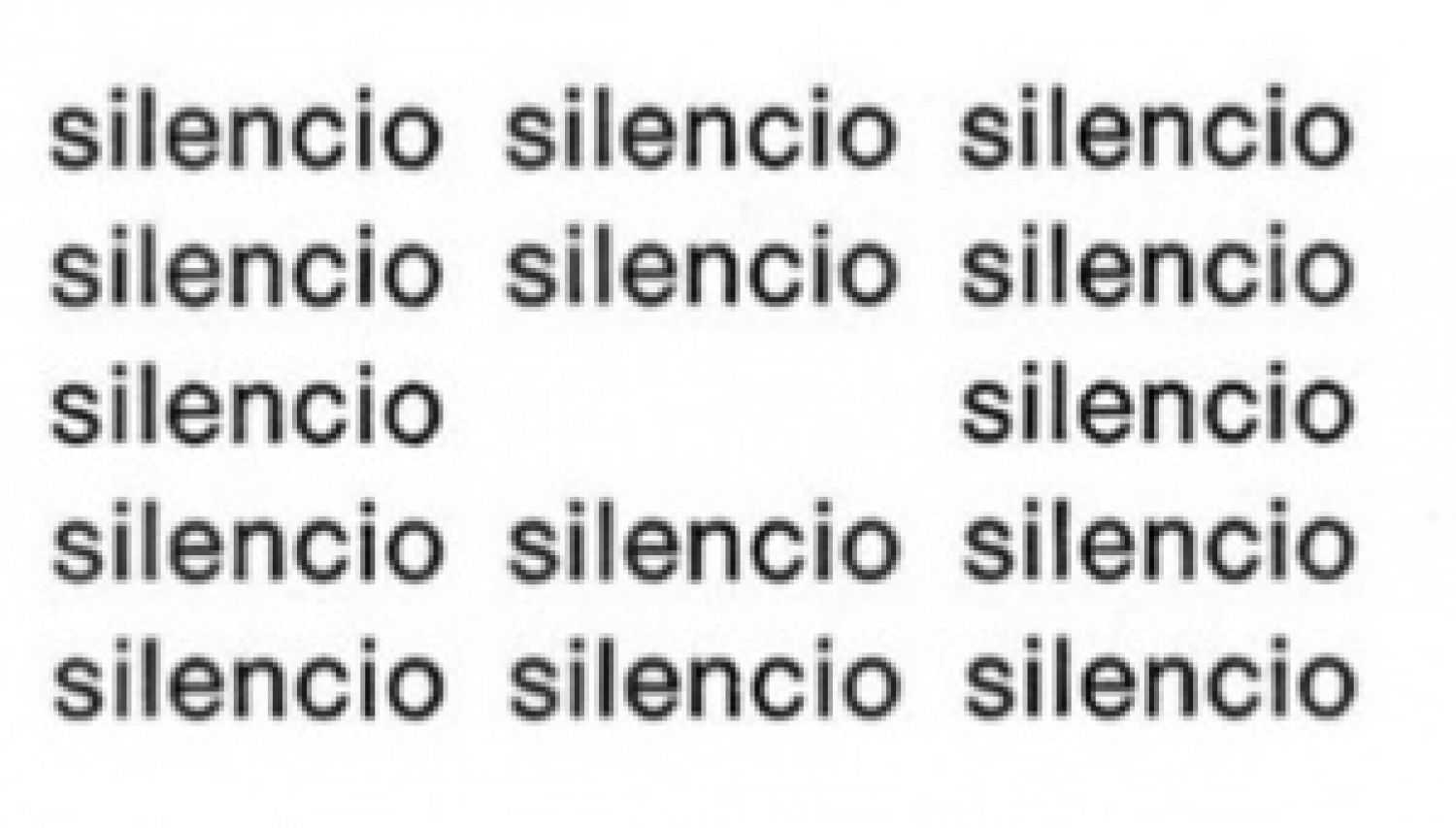

«An enemy is someone whose story you have not heard» (Slavoj Žižek). There was an urgency in Viesulas’ work to recognise the disfigurement on either side of a partisan debate. Where politics takes precedence over our common humanity, estrangement results. The universal human experience of estrangement is at the core of Viesulas' artistic vision. In work such as Toro Desconocido (1960), which he created as the first artist-in-residence for the Tamarind Workshop, he explicitly championed the unknown, the unsung. It is dedicated to «all who give their lives in obscurity». Later work kept returning in ever less figurative depictions, to the parallel stories of the suppressed, the marginalized and the exiled. Lives obscured by official narratives or forgotten in the march of history may yet be sources of inspiration. «We are the other», cycles such as Yonkers (1967) seem to say, inviting the viewer to share, to identify with, the experience of grief through the eyes of strangers, being in the company of someone who learns that their children have perished in a house fire. The prints in this cycle are a summons to empathy, an elusive quality during a century riven by ideological divides, separating people from origins, from others and from themselves.

«Who's fighting and what for? Why are we fighting?» pleads Mick Jagger onstage at the Altamont Free Concert in 1969, as Meredith Hunter gets stabbed to death by the Hells Angels, all captured on camera in the documentary Gimme Shelter. From my vantage point, the year reads like a catalogue of chaos and shifting sands. The very Biennale itself was like an opera buffa. Many of the participants works were detained at customs at the time of the opening. Dan Flavin had neon tube sculptures installed in the Italian Pavilion, but there was no electricity to illuminate them.

Nonetheless, Viesulas’ work did make it onto the walls, and he created Overpass (1970) an original print cycle in its entirety as «artist in residence» in the US pavilion. Offsite, the Mark Rothko estate organized a show at the Venetian Museum of Modern Art, where the majority of the paintings exhibited had never been shown publicly. For a short time, these two fugitives from the fringes of Europe found a home for their vision in Venice. With the materials he was able to salvage in exile, Viesulas chose to become an artist rather than an ambassador for a nation state. His work sought to transcend the narrowly political, the national and the ethnic. Loss is not confined to national boundaries, or any particular tribe. He sought to convey his personal experience of uprootedness through a universal idiom of abstraction. I like to think of him as an ambassador of statelessness, an emissary for empathy.

Empathy is becoming an increasingly scarce resource in our digitized, atomized world of narcissistic self-regard. Technology is spellbinding. Notes on Image and Sound (1965) might be re-interpreted as a meditation on the beguiling powers of the illuminated manuscripts we all carry in our pockets these days. However, technology may be creating a cognitive dislocation, and risks sending us into a solipsistic self-exile. How can we recognize ourselves in the Other, if all we see is our own self-reflection? In an era where the nation state appears to be on the wane, we find ourselves in a «stateless’ state of mind. Once estranged by wars of ideology, we may become estranged by technology, as the ideology of the marketplace becomes all-consuming.

In Venice in 2019, all seems placid on the surface, the varnished gloss of consumerism, the entire city and its art an infinite opportunity for the selfie. And yet a tide of disquiet laps at these shores. We may be more busy performing our lives on social media than actually living them, selling our own brands so as to assert our identity in the shifting sands (or indeed disappearing sands) of our own troubled age. This disquiet is brilliantly and beautifully amplified by Sun & Sea (Marina), the Lithuanian pavilion which won this year’s Golden Lion award. This was not a case of name recognition for artists Lina Lapelytė, Rugilė Barzdžiukaitė and Vaiva Grainytė. Nor is there a national concept at play, or any particular breed of politics on display. This is cultural diplomacy on behalf of all of us. An opera, on the beach, about the end of the world. We eavesdrop on our own personal anxieties and fears by listening to the laments and puzzlements of the performers we hover over as if we were their disembodied spirits, part and parcel of this echo chamber of deferred catastrophe. We all know that it has become easier for us to imagine the end of the world than an alternative to our current system of governance. Spectacular renditions of climate apocalypse overwhelm the collective imagination.

Siege mentality. We’ve laid siege to the natural world, and so feel besieged ourselves, paralysed by visions of dystopia and the knowledge that our longed-for techno-consumerist utopia may be bringing them ever closer. There is no utopia, this work seems to say. There is no dystopia, either. Only you, and me, and others just like us, right here and right now. Who’s fighting? And what for? Why are we fighting? Fifty years on, as the proxy wars of today’s nation states create yet another generation of displaced persons, I ask myself the same question. And if not to welcome them and to hear their stories, what good is our art? How is it different from the billboard advertising of today, or the propagandist manifestos of yesteryear?

Standing at the water’s edge looking out over the lagoon, I imagine my parents in 1969, a melancholic dreamer and his young bride on their honeymoon around the world, navigating actual and diplomatic minefields from Cambodia to Iran. «1969: année érotique». Somehow my parents found love in the midst of the madness and chaos of that calamitous and moonstruck year. The first inkling of me appeared in Calcutta that year, and I arrived in this world just in time for the Biennale circus of 1970. Make love, not war. Make art, not politics. Words to live by, half a century later.

Many thanks to Nuno Miguel Proença for the skilled translation into Portuguese and to Katherine Sirois for editorial direction.

I’m also grateful to Wrong Wrong for welcoming this feature.