Sekula (Un)Forgotten Space

Cristina LopesIntroduction

Across four decades the photographic and written practice of Allan Sekula has provided an object lesson in the possibilities for an artistic commitment to labor’s cause and for the exploration of the world of late capitalism from a radical-left perspective. Since Fish Story (1988-1995) Sekula has conceptualized, through his art and writings, the maritime space as a way to explore and expose epistemological questions related to labor and to the nature of globalized capital. In those photographs, he investigates the possibilities of artists confronting ecological disasters, violence and death related to migration, and different events connected to imperialism and colonialism. Moreover, tanking in account that in certain insights he looked from that insider's position as he critiqued photography and the circumstances of its production and consumption. Premises that Sekula supports leads to some contradictions with regards to social responsibility. Finally, object agency may be seen as part of a larger intellectual trend which perceives agency as a dynamic global force. As Sekula remind us in exposing what the medium failed to represent – women, laborer’s, minorities and the institutional structures that reinforce cultural biases.

Fish Story and other stories

With the exhibition Fish Story, was reconstructed a realist model of photographic representation, while taking a critical keek towards traditional documentary photography. Though there is a long artistic tradition of depicting harbors and ships, perhaps not much contemporary artists are committed to it. In Fish Story Sekula picked up this tradition, given account of maritime space not only as a visual space but also as a socio-economic one. Fish

Story was his third project in a related cycle of works that deal with the imaginary and actual geography of the advanced capitalistic world. A key issue in Fish Story is the connection between containerized cargo movement and the growing internationalization of the world industrial economy, with its effects on the actual social space of ports.

One way to understanding Allan Sekula’s artistic productions over the past decades has been to identify it in terms of «critical realism» as Buchloh point it. Realism that considers the research methods of a reflective artistic practice, including, among other elements, theoretical and essayistic writing, photography and essay film. Foundational for such a methodology is the dialogue and participatory observation that the artist developed with workers, activists and scholars in order to explore existing and potential models of collaboration. Sekula stands as one of very few contemporary artists, to have continually resisted the conventional division of labor between practitioner and critic.

Sekula works throughout to resist the possibility of any easy interpretative resolution or reductive of Fish Story. In keeping a critical realism that recognize the limitations of traying to apprehend the enigma of capital 46 . Within each titled chapter of photographs, the images display a wide range of types, so that no single pictorial mode predominates. There are microscopic close-ups as well as panoramas and, between the two, there are highly detailed and carefully composed views of sea, coastal, factory and shipyard scenes. On land the viewer may access to «forgotten» towns, integrated in the global circulation of containers, within which individual people occupy a variety of positions. Often absent, obscured or incidental, sometimes central, mostly at work on specific tasks. The people include fishermen, rescue workers, welders, dockers, market traders, as well as the unemployed, children and families. Sekula displays a model of photographic visibility that, by recognizing its lacks of adequacy to represent a «bigger picture» strives to be adequate to the complexity of the subject at hand.

The (Un)Forgotten Space

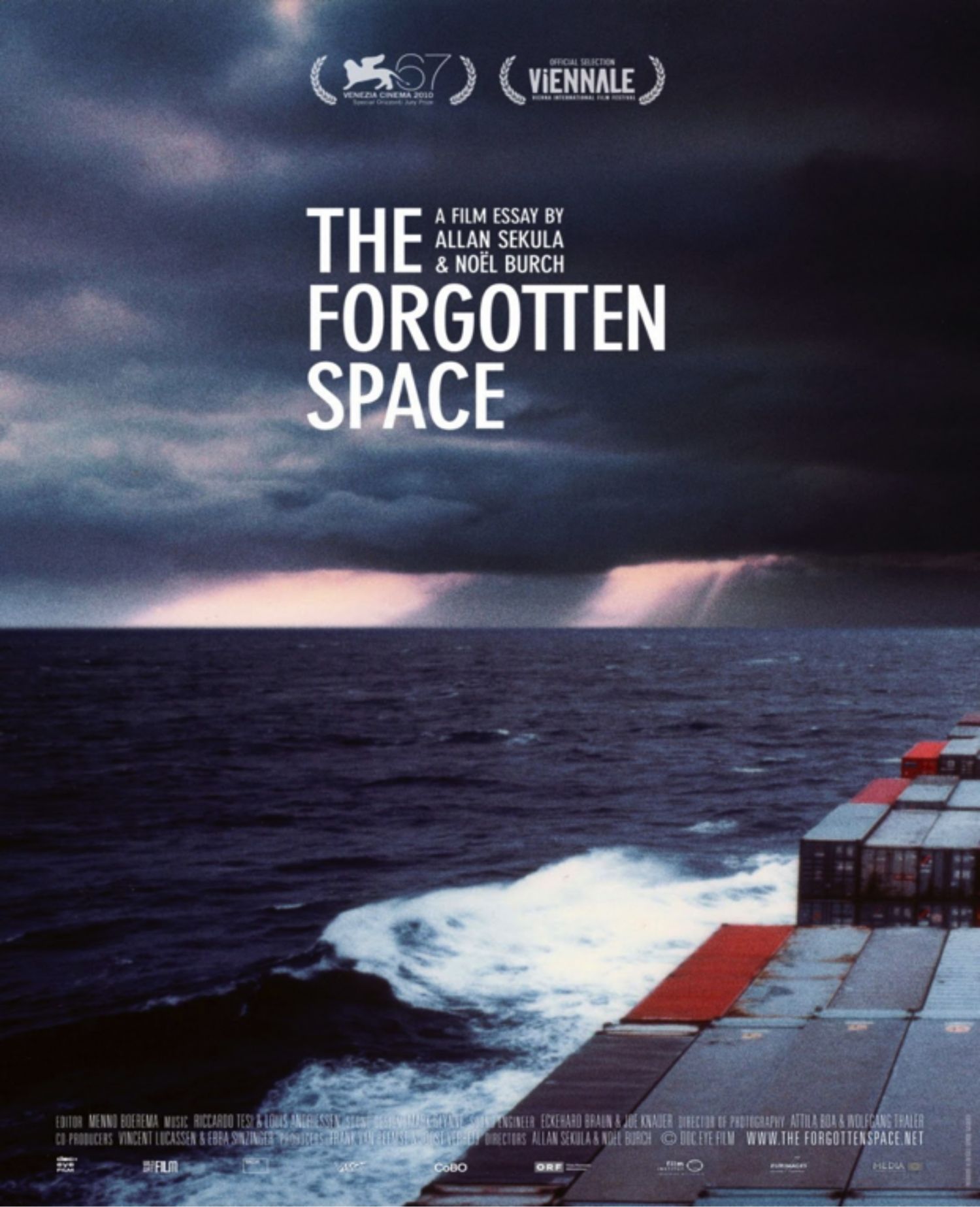

That is the name for the essay film, with 112 minutes length that received the Special Orizzonti Jury Prize of the film festival in Venice in 2010. Sekula made it in collaboration with film theorist Noël Burch. The Forgotten Space, a documentary film on containerization and world trade along the sea. Not only became one of the most striking essay films of recent decades, it’s also the most farsighted film on the effects of globalization, on both individuals and nation, tackled through the prism of containerization and maritime trade. The sea itself turns out to be the forgotten space of the title, since most people are unaware that more than 90 per cent of the world’s cargo travels by sea, through gigantic ports such as Los Angeles, Hong Kong, Bilbao, and so on, some situated at such a remove from their host cities as to be almost invisible. Far from being the repository of romantic visions, of great voyages of discovery and adventure, the sea, thanks to containerization, is the scenario for the globalized trade, and it serves also as a bridge for different stories and encounters. This recent reality is presented by Burch and Sekula’s film with measured, eloquent rage.

The idea for The Forgotten Space came about from a photographic book Sekula published in 1995 called Fish Story, and in particular one essay in it called «Dismal Science», which led to lengthy and productive discussions with Burch about perceptions and ideologies of the sea. Gradually, as the film was shot and assembled over the course of six to seven years, in several countries including China, Holland, Hong Kong, Spain and the US, a script and a thesis emerged. It became a way of showing the globalized capitalism, enabled by the explosion of mechanized trade on the oceans, using cargo as a broad political category. The filmmakers look at the container, as the carrier of multiple meanings, as well as the providers of a referred image. A stack of multicolored containers on a cargo ship with the horizon in the distance, became the image of the poster for the film festival in Venice in 2010.

In some ways the sea becomes a mirror of the financial world, with similar invisible, destabilizing flows and currents across the globe making it impossible to grasp totally, in fact Burch and Sekula were able to make explicit reference in their narration to the financial crisis.

For Sekula, a «critical representational art … that points openly to the social world and to possibilities of social transformation» remains the only art worthy of an oppositional politics, as well as a necessary counter to a situation in which «the old myth that photographs tell the truth has been replaced by the new myth that they lie». (Risberg 1999) says in other words, that to understand the notion of the play of signifiers as to believe in an openness of signification is no less false than a belief in photography’s total and transparent objectivity. In this sense we should rather, to look on the historical, social and institutional affiliation of photographic meaning, of the place of photographs within different discourses and image context. Traying to understand meaning as delimited within changeable and overlapping contexts.

The key to Sekula’s activist endeavor is to relate his necessarily incomplete impressions of the global capitalism dialectically. Above all, this means to recognize the inherent contradictions of a complex and continuously changing world-system, and indeed to insist on contradiction as the very locus of change. The picturing of social contradictions and, economic disparities, under global capitalism is at work, during all the making of Fish Story. for instance, in the geo-economic contrasts between conditions of rise and decline in different corners of a post-Soviet, globally interconnected world. In any case the attempt to set out and exhibit certain working conditions and to make a valid contribution was well achieved. Finally, Sekula’s while politically driven, his message is never pushy. Mostly in the case of the Forgotten Space it is primarily investigative in nature. Sekula and Burch capture exceptional scenes, often more poetic than polemical.

Bibliography

Sekula, Allan. (1999). «Dismantling Modernism, Reinventing Documentary (Notes on the Politics of Representation)», in Risberg 1999, p. 120, Sekula in Risberg 1999, p. 239.