photography : object : photographed

Xavier MartelTechnique of reproduction – duplication/replication – of an engraved, drawn or painted image... this is how one could designate the invention that Nicéphore Niépce (1765-1833) is developing at the beginning of the XIXth century... What? The image (object) engraved (manually), and its reproduction (physical-chemical): image of an image, object of an object. Niépce seeks (and finds) a way of reproducing engravings (and images in general) in order to perfect, in order to compete, with lithography... with, in the background, an underliyng idea, a desire for industrial application.

The image (a fortiori photographic), no doubt, is object (assuredly complex).

But... soon the engraving to be reproduced is replaced by «a point of view» (image preserved at the University of Austin, Texas)... «a set table» (image «lost» circa 1900) and, from the moment of its revealed birth, photography is no longer limited solely to reproduction, but to the production of new images, new objects representing... selected objects, found. The object found is necessarily chosen, otherwise it does not exist: it remains an object, indifferent, in a limbo.

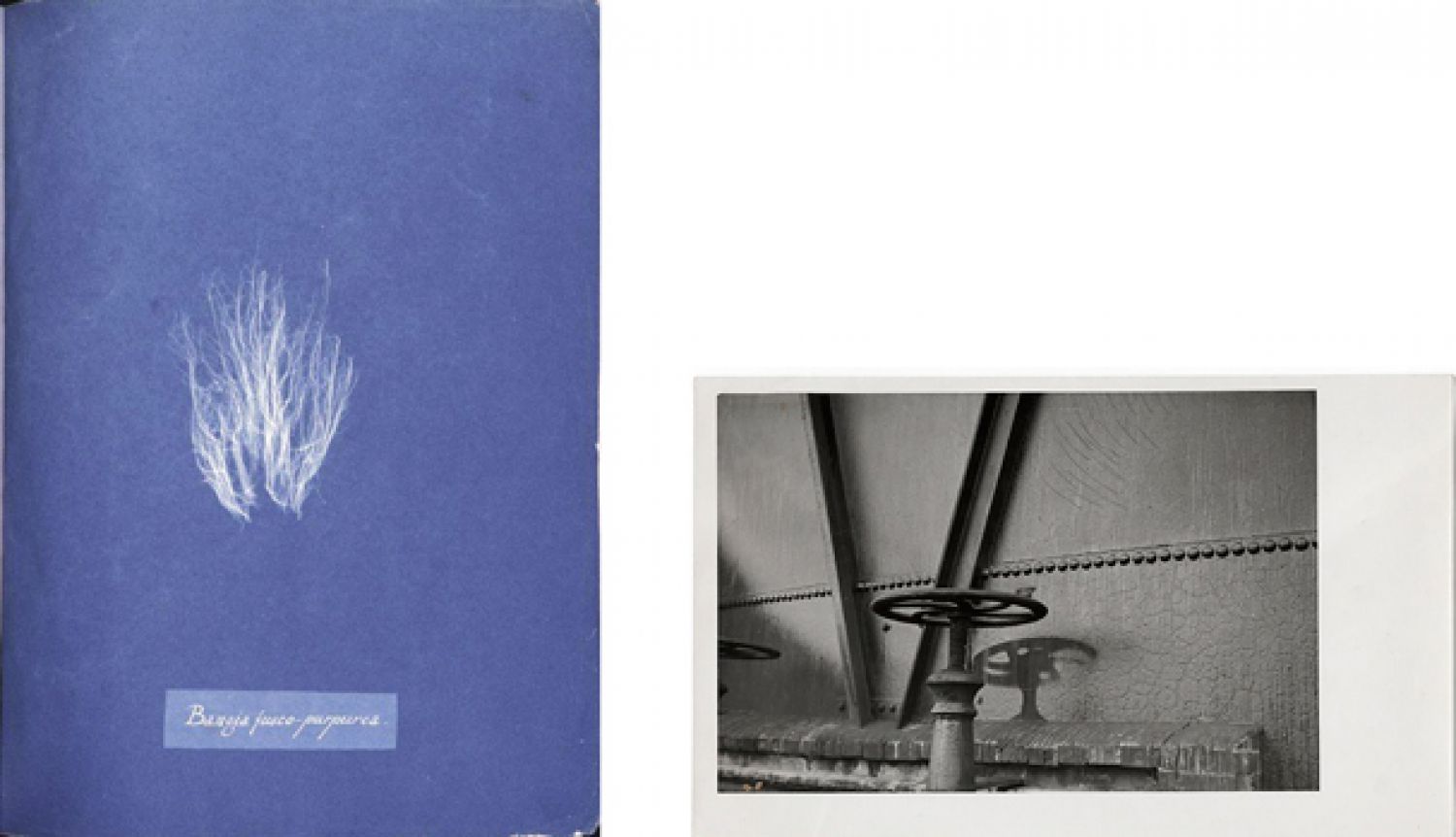

One of the origins, minimal practice, of photography, is the impression of the object on a sensitive surface: the photogram. Anna Atkins (1799-1871), botanist, meticulously highlights the imprint of her objects of study. These plants, algae for the most part, are gleaned, selected and then immortalized by their imprints: Cystoseira fibrosa, 1843. Specific shadows (the cyanotype reacts essentially to ultraviolet rays) of objects, enduring beyond the disappearance of the thing, these frames find a morbid echo in the projected «shadows» of objects (things and people) on the walls in Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6 and 9, 1945.

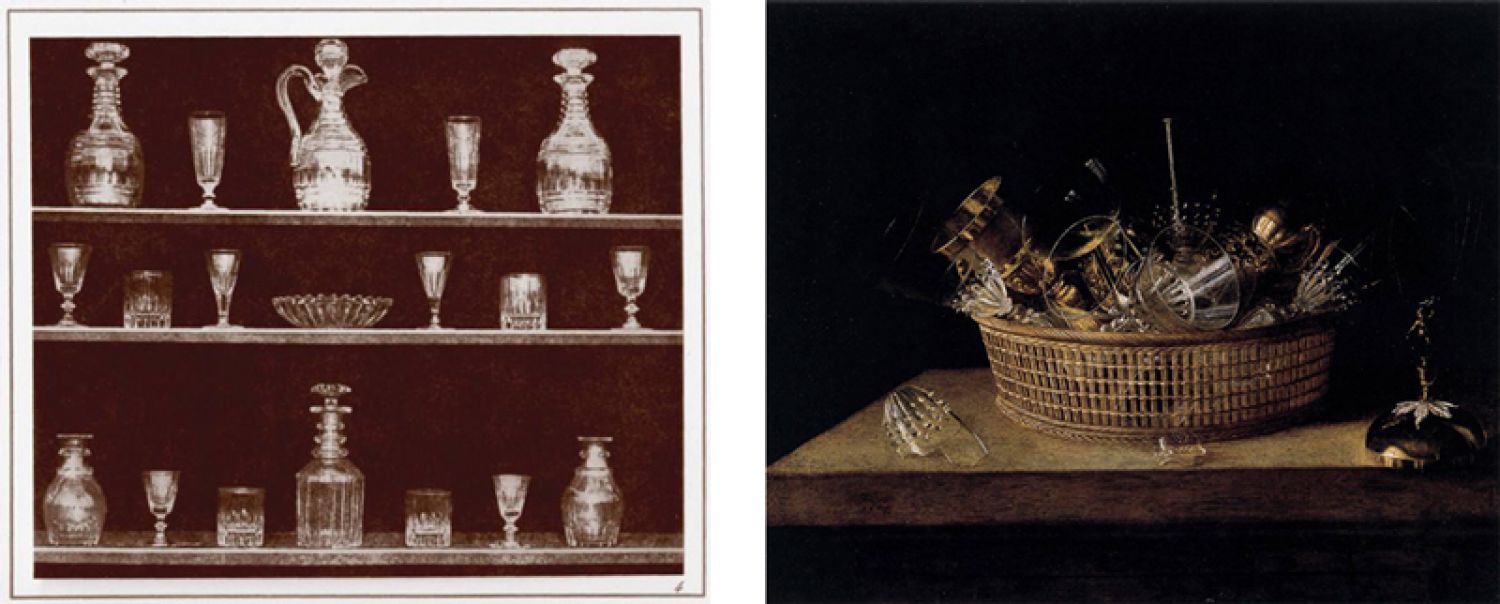

At the same time, Wiliam Henry Fox Talbot (1800-1877) demonstrated all the virtuosity of the new images. Undoubtedly, from the moment of its invention, photography is adorned with all its attributes (helmeted and armed like Athena emerging from the head of Zeus) and it has the potential to reproduce any object. In his work Pencil of Nature Talbot attempts to draw up a sort of inventory – not exhaustive – of the possibilities of photography. It is therefore quite natural that in the first planks one finds of ceramics and glass, materials which are well known to be difficult to represent – one thinks of the virtuosic painters of whom Sebastian Stoskopff (1597-1657) who offers an excellent parallel with his Nature morte au panier rempli d'objets en verre.

Plate IV of Pencil of Nature originally titled Articles of Glass with a Dark Background advertises and documents photography's reproductive capabilities... but it is one of the very first photographic vanities, a work in itself. One can not help thinking that Talbot, when he calls his work Pencil of Nature, makes a play of words: Nature is in English (and in French) the Greek Physis (the whole of the perceptible world) and the pencil belongs to Physics, photography thus presents itself as the best tool for seeing and studying nature.

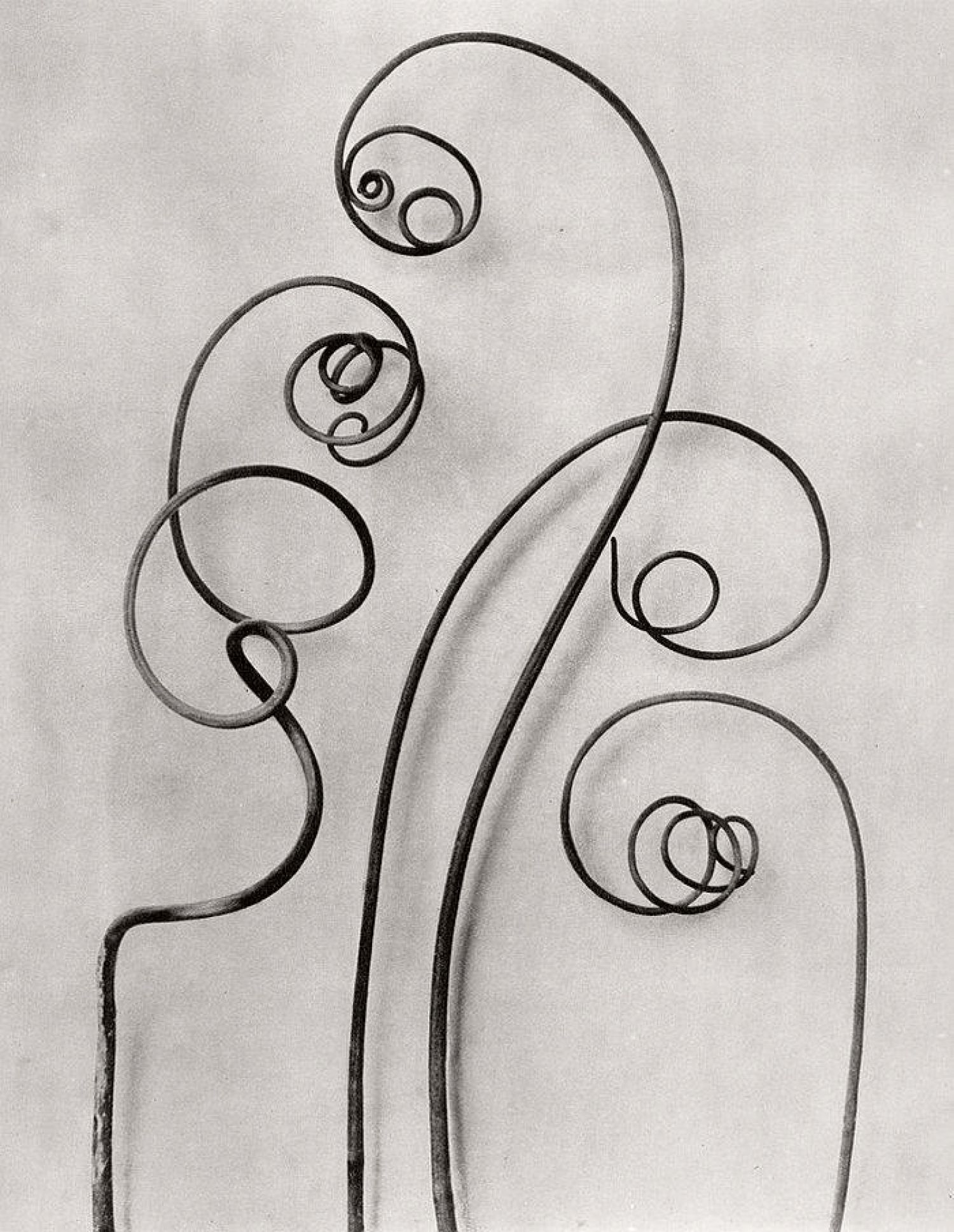

Photography is, always and absolutely, between document and work of art... ambivalent. The point of view determines the meaning, the interpretation. Sometimes the manufacturer, the artisan, the one who constructs the image, who produces photography declares that he does not make works Karl Blossfeldt (1865-1932) – but also Eugène Atget (1857-1927), his contemporary – are good examples. Thus, Professor Karl Blossfeldt in making his documents for graphic studies, copies and models, inevitably created works in themselves. The object (still the plants), found and chosen, is recreated through its photographic image: Bryona alba, Ranken, nd. Blossfeldt is one of the relays in the long list of photographic poetization of objects. And although he says that he ONLY makes documents («My documentation on plants is intended to help restore the link with nature...» – Wundergarten der Natur neue Folge von Urformen der Kunst, 1932), it is evident that it is useless to believe them. The viewer does the work... or the document.

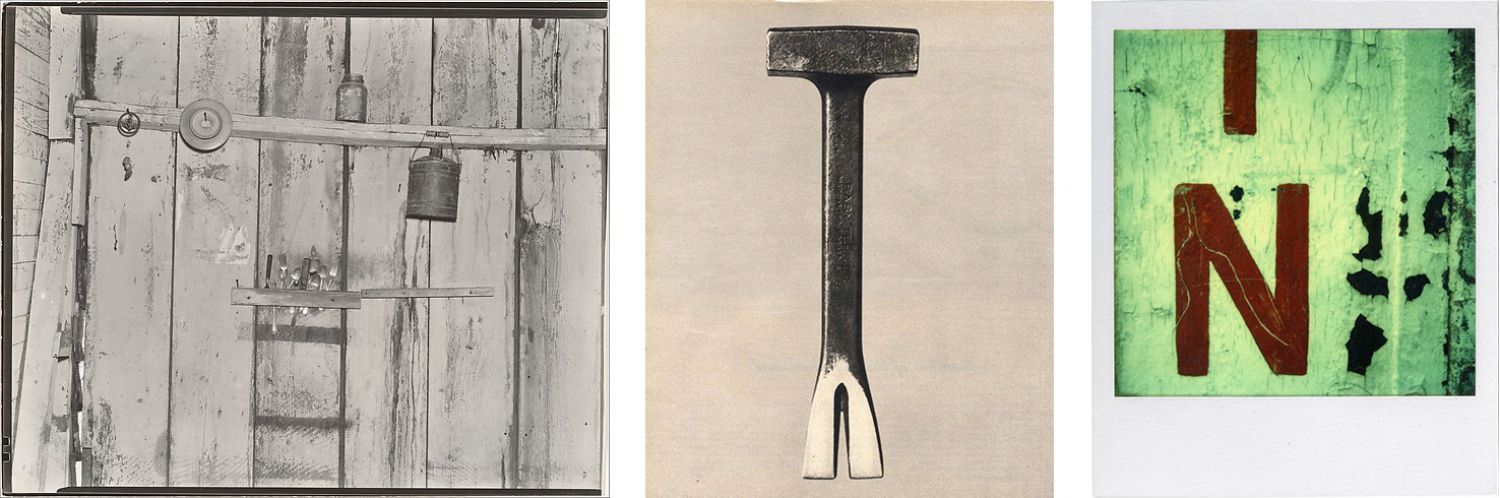

Walker Evans (1903-1975) is an unmissable monument in the history of photography – more specifically than Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968), which, unfortunately, will not be mentioned here –, and precisely when he is photographing objects. Elements of a daily poetics, photographs of objects punctuate his exploration of a destitute America; it is the ultimate trace of presence, of human activity, like kitchen utensils on this wall: Kitchen Wall in Bud Field's Home, Hale County, Alabama 1936.

In the post-war Renaissance and victorious America, he praises its everyday objects and utensils in Fortune magazine in April 1955: Baby Terrier Crate Opener, by Bridgeport Hardware Mfg. Corp., 69 cents (page 104):

«(…) Aside from their functions — though they are exclusively wedded to function — each of these tools lures the eye to follow its curves and angles, and invites the hand to test its balance. (…) In fact, almost all the basic small tools stand, aesthetically speaking, for elegance, candor, and purity. »

And, to the end, in his last images, with the polaroids of the 1970s (untitled, 1974) one sees his preoccupation for the object. Not only does the object in itself interest him, he is fully conscious of making other objects, documents and works. Signs, letters and numbers, are made concrete, become abstract images, become scultpures flattened.

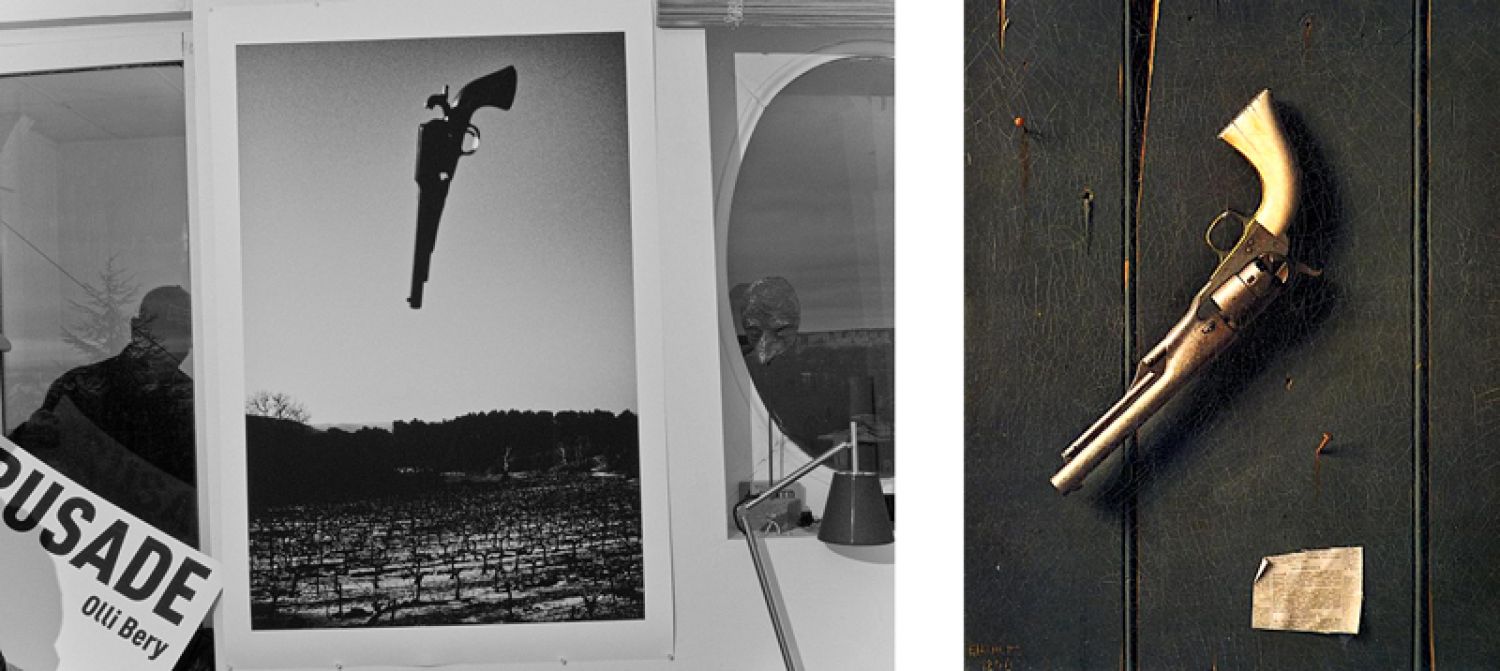

Starting from the object sign of Evans, the object, throughout Olli Bery’s work (1973-), makes a sign. An image (an object) is recurrent, the image of a revolver pistol... the object as a signature. This pistol is the claim of shooting, the photographic shot, which echoes the violence of the image. The signature here, punctuation, calls for calm (after the trigger – «taking reality makes a noise not possible» – Denis Roche (1937-2015), «Photographier» (1978) in La disparition des luciolles, 1982... the gun barrel points down... it does not threaten (more) like the one photographed in the hand of a child by William Klein (1928-). This is only a clue, the reminder of the possibility of violence, from camera to firearm – life and death. What could be more faithful than a revolver?: The Faithful Colt, 1890, painting by William Michael Harnetts (1848-1892).

Yannick Vigouroux (1970-) often finds objects/things photographed... these things, normally perceived inanimate, here, vibrate!... live! Far from claiming the spirit photography, Yannick Vigouroux, however, empathizes with these objects... the soul of these objects – randomly encountered – are recorded by the photographer. It is certain that even industrial objects, those to the glory of the great capital, have received but a tiny part of the Creator Spirit ... in this they are animated. They live, it is the homage that Yannick returns to these objects, even the most humble.

Finally, because we must limit ourselves, so many objects around us, so many photographers from around the world, finally the object returns as trace... wreck, it ends (?) Its life, by the sea. Didier Tatard (1966-), modern rhyparograph, as Anna Atkins, gleans and selects meticulously. Representation of waste, sign of human activity... sign of the congestion of the consumer society... index of pollution. Objects abandoned, readymade reactivated, these photographs seem to carry in them the sadness of the abandonment.

The latter in particular – a blue ball – still blue so blue – in the middle of pebbles... perhaps our blue planet is increasingly artificialized, objectified, lost, buried in piles of objects of mass production... useless, unnecessary goods.

«(...) images present themselves as objects that can be examined. These objects are capable of producing discourse and being supported by knowledge. Even if their object status is fundamentally problematic, images appear as a sensible reality offered simultaneously to gaze and knowledge.» Marie-José Mondzain, L’Image peut-elle tuer?, Bayard, 2002.