Pathos and portrait according to Romeo Castellucci

João Francisco FigueiraAmong those who saw Gluck's Orphée et Eurydice at La Monnaie, in Brussels, in June-July 2014,[1] it was with effort that many held their tears, while others wept conspicuously. The beautiful and melancholic music of Gluck-Berlioz, the misfortune of Orpheus, that in act II pleads «Laissez-vous toucher par mes pleurs...»,[2] certainly played a role in this effect. Indeed, both the music is touching and the narrative covers the path between the brutal separation of the two lovers due to the death of Eurydice, and her redemptive return to life and to her partner.

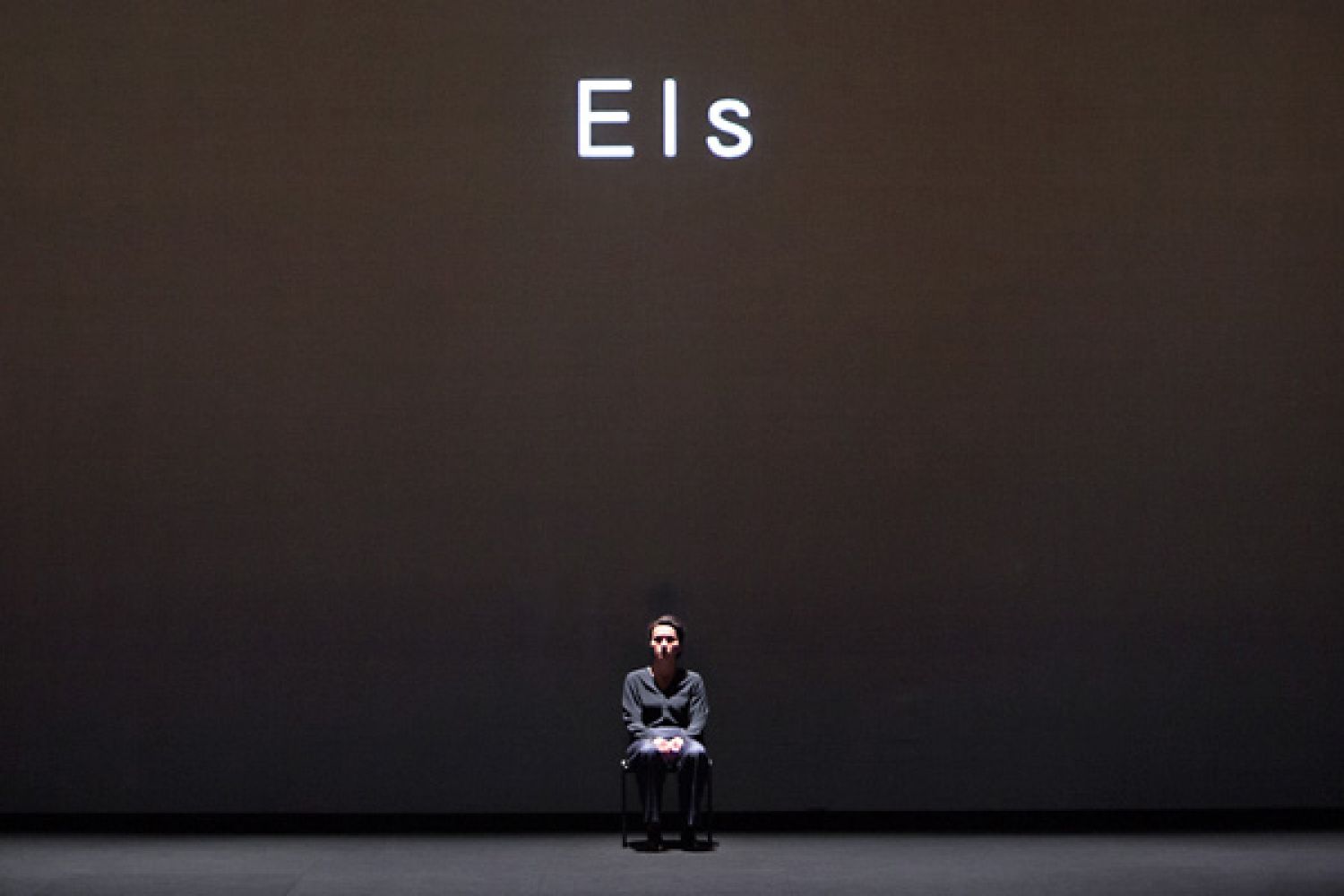

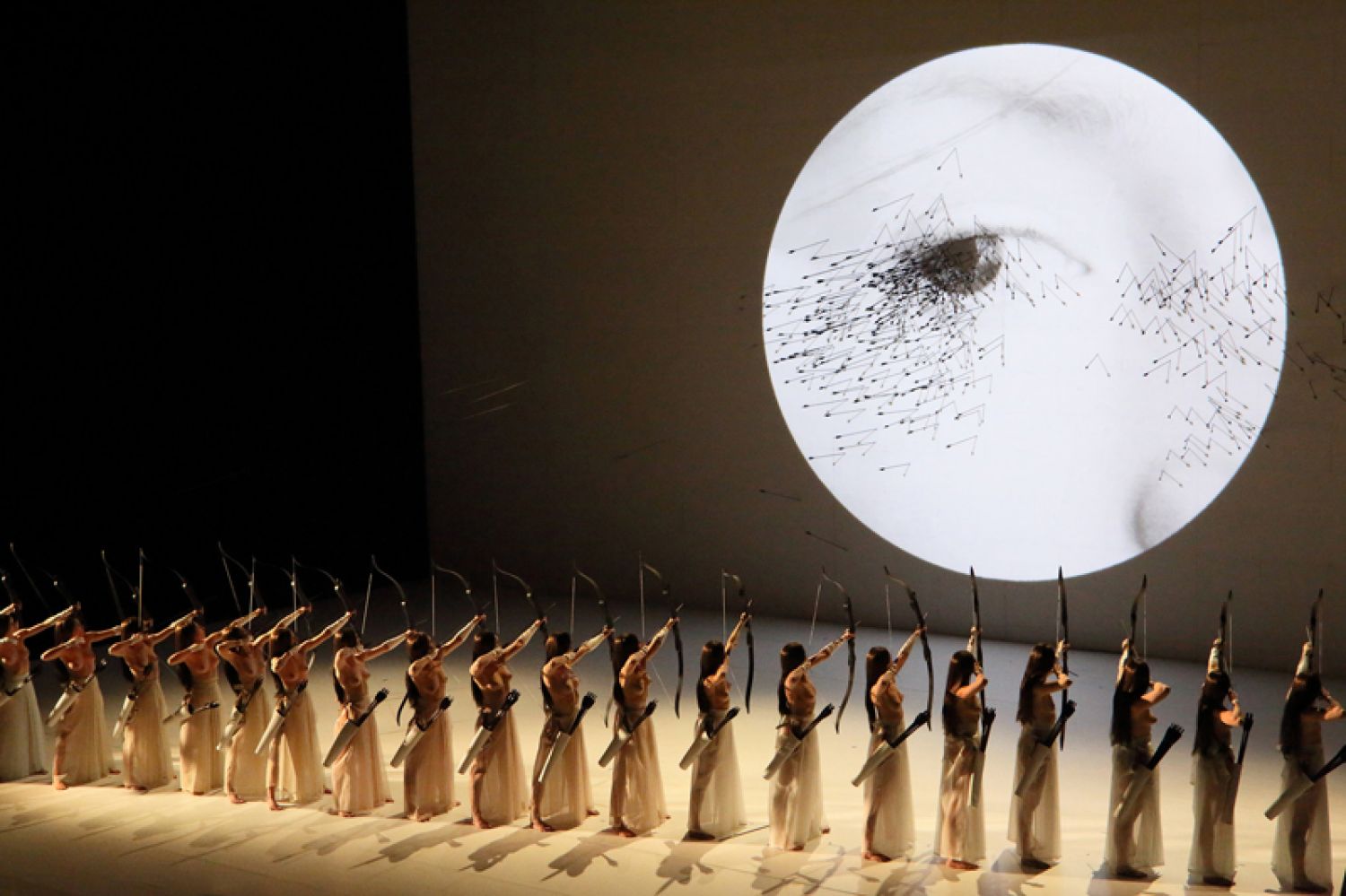

However, the strong emotional impact of the production must fundamentally be credited to the choices and skill of its director, Romeo Castellucci. He starts by frustrating the expectations of standard operagoers, by presenting them a concert version of it. For about half-hour during act I, we sit before the dark screen and Orpheus (fig. 1). While Orpheus bemoans the retreat of his beloved Eurydice into the Hades, the abode of the dead, the story of a bedridden woman, «Els», suffering from «locked-in syndrome», is narrated in white captions. A singer will sing the lines of Eurydice, but that will be it. Castellucci convokes Els, and her life story, as an avatar of the mythic character. Then, in act II, in relation with the journey of Orpheus towards the Hades in order to rescue Eurydice, we are offered a long road travelling live broadcasted from the periphery of Brussels. We are obviously driven to the hospital where Els is admitted. The screen is at this stage used for the video projection. Then in act IV, as a consequence of Orpheus breaking the godly decree imposing that he should not look at Eurydice, something that she neither understands nor accepts, the screen shall become excessively bright and so the light devours the images of Els and Eurydice (fig. 2).

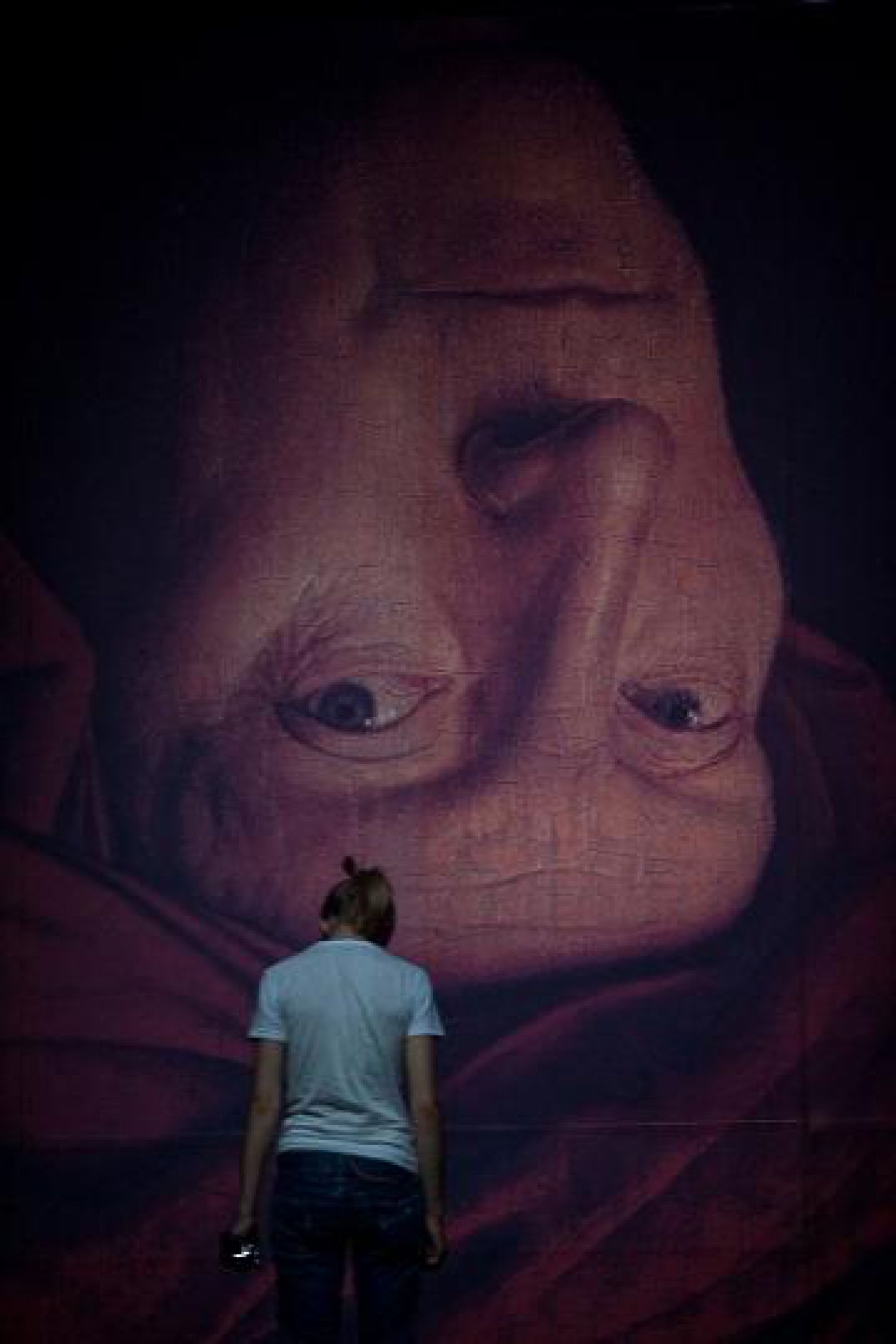

When Orpheus for the first time encounters Eurydice, a close-up of Els face is framed and ostensibly presented to the audience. It is the first climax of the show. After punishing Orpheus, the gods will at last allow him to rescue her for good. It is so that the camera shall approach Els and frame a second and frontal close-up, which constitutes the second climax the show, before its end (fig. 3).

At the end of the opera, people sat transfixed on their chairs. The theatre «was veiled in silence, consternation, with some spectators wiping away tears».[3] Many spectators took some time to regain their composure.

While music and drama certainly play a role in the powerful effect upon the audience, what definitively singularizes this production in relation to a standard one is, on one hand, the consideration of Els and, on the other hand, the specific choices of the mise-en-scène, turning the opera performance into a concert, then a cinema screening, for finally coming to the close-ups of her face. There is also an exquisite attention to time, an absolute control of the slow pace at which the transformation of the initial dispositif occurs.

In a fine book on the theatre of Romeo Castellucci, Dorota Semenowicz comments on both aspects, the mise-en-scène and Els, considering that show is «one of Castellucci's simplest, most ascetic works».[4] As to its efficacy, Els’s long gaze is mentioned in particular: it makes us «anxious, tense, embarrassed, ashamed, because we have the impression of being voyeurs, of intruding on someone's privacy; it is the manifestation of our fear of the loss of someone close, of helplessness related to it and, at the same time, of sharing Els's plight».[5] Briefly, we, as mortal beings, are sensitive to someone else's plight.

Yet, there is no relation with Els – that happens to be a pseudonym –, except, and this brings me to the first aspect, through a montage of media and images, carefully crafted, neither simple nor ascetic, but indeed very sophisticated, particularly the close-up and the gaze. The collusion of the bedridden person with motives and media, both contemporary and old, unexpected and counterintuitive elements, constituting a rather heterogeneous ensemble, enormously intensifies the performance.[6]

Let us start by Els, that is to say, by the body of the non-actor. Castellucci is interested in bodies stripped of theatrical and cultural mannerisms, not penetrated by the spectacle so pervasive in our societies. Bodies that therefore have a singularity and an intensity of their own to deliver. Three examples can be given, from important shows of Romeo Castellucci and a recent one.

The first is the Antony of Julius Caesar, a work of 1997 resumed in 2014 as Julius Caesar. Spared parts.[7] The person doing the role, Dalmazio Masini, is a laryngectomee and as such it is with difficulty that he will say the famous words in praise of Caesar:

[I am] a plain blunt man,

That love my friend [...]

[...] I have neither wit, nor words, nor worth,

To stir men's blood: I only speak right on;

I tell you that which you yourselves do know;

Show you sweet Caesar's wounds, poor, poor dumb mouths,

And bid them speak for me.[8]

Besides the effort in uttering the lines, that is indeed conspicuous, Antony speaks on the higher eloquence of Caesar's wounds, from a wound, his own (fig. 4). The choice both intensifies the performance, is fully justified in relation to the text – as a bodily and literal translation of it – and avoids theatrical truisms. It goes without saying that this is the joy of a part of the audience and alienates another part of it. Either way, the artistic choice is very clear and well grounded.

The second example is the lone baby scene in BR.#04 Brussels (2003).[9] It is preceded by a woman dragging a cleaner's trolley and mop, cleaning the empty space, detached or alienated from this world. It will be followed by a scene in which two policemen violently beat with their truncheons a third one. So, what does it happen in the middle scene of the lone baby? Very little, almost nothing. As the curtain opens, at the centre stage sits a baby with about 6 months, a few toys around, surprised by our presence and surprising us, simply for being there. At the back of the scene there is a sort of mechanical mask saying «one, two, three... a, b, c...», in what is a rather awkward lesson in counting and spelling (fig. 5). It has a sure impact:

In Zagreb, when we performed [BR.#04 Brussels], it was beautiful. The baby was magical, she had the ability to suspend time. The show stopped. As if there was no more show. Everything was suspended. Who is that? Who are we? It was like looking at flames. It was like being bewitched. Nothing happening. Everything floating.[10]

A third and last example is constituted by the «the supper» of the recent La Passione (2017), after Bach's Passion According to Saint Matthew, a performance commissioned by and presented in Hamburg. While at the back of the stage orchestra and chorus perform, at front stage a number of scenes unfold. «The supper» occurs in relation to the biblical and Bachian narrative of «the last supper». In black captions is indicated that in Hamburg there is a clinic that provides care to people in the vey last moments of their lives and the staff includes a chef that can prepare a «last supper». It is mentioned the case of Heinz Stefan Bartkowiak who as last supper had Greek yogurt and champagne, and it is so that ceremoniously we see persons carrying a refrigerator and these consumables (fig. 6). Naturally in this case it is the absence of the body that is made present. Also in this case the scene makes apparent the literal inscription in a show of something that is of the order of the real. «Real» in the common sense of the word as well as in the Lacanian sense, as a powerful intrusion of something into the symbolic order, piercing and troubling it.

The consideration of Els in Orphée et Eurydice derives from the same search of a unique body that can deliver a particular intensity to the performance, in what is a mistrust in relation to standard theatre, spectacle, contemporary forms of social life, and a trust in another theatre, fundamentally disalienating, epiphanic, with an open nature. It is not a gratuitous choice, insofar as deeply rooted in a reading of the play. It represents the author's understanding of what may be the uncertain location between life and death, the Hades, from where the «dead» still can be rescued; in fact, they simply are cut away from our world. In this sense, the move of Castellucci is not at all a cheap strategy for sequestering the emotions of the spectator, but an unprejudiced and serious reflection on the play, theatre and the contemporary world – a fully justified artistic choice.

As to the mise-en-scène it is indeed a sophisticated montage of heterogeneous elements, in some cases acting as ghosts behind the screen. For the sake of economy I will focus on a few aspects in relation to the close-up and gaze.

The facial close-up, constituting the two climaxes of the show, was identified by Gilles Deleuze as the pathos-image par excellence:

It is this combination of a reflecting, immobile unity and of intensive expressive movements which constitutes the affect. […]. There is no close-up of the face, the face is in itself close-up, the close-up is by itself face and both are affect, affection-image.[11]

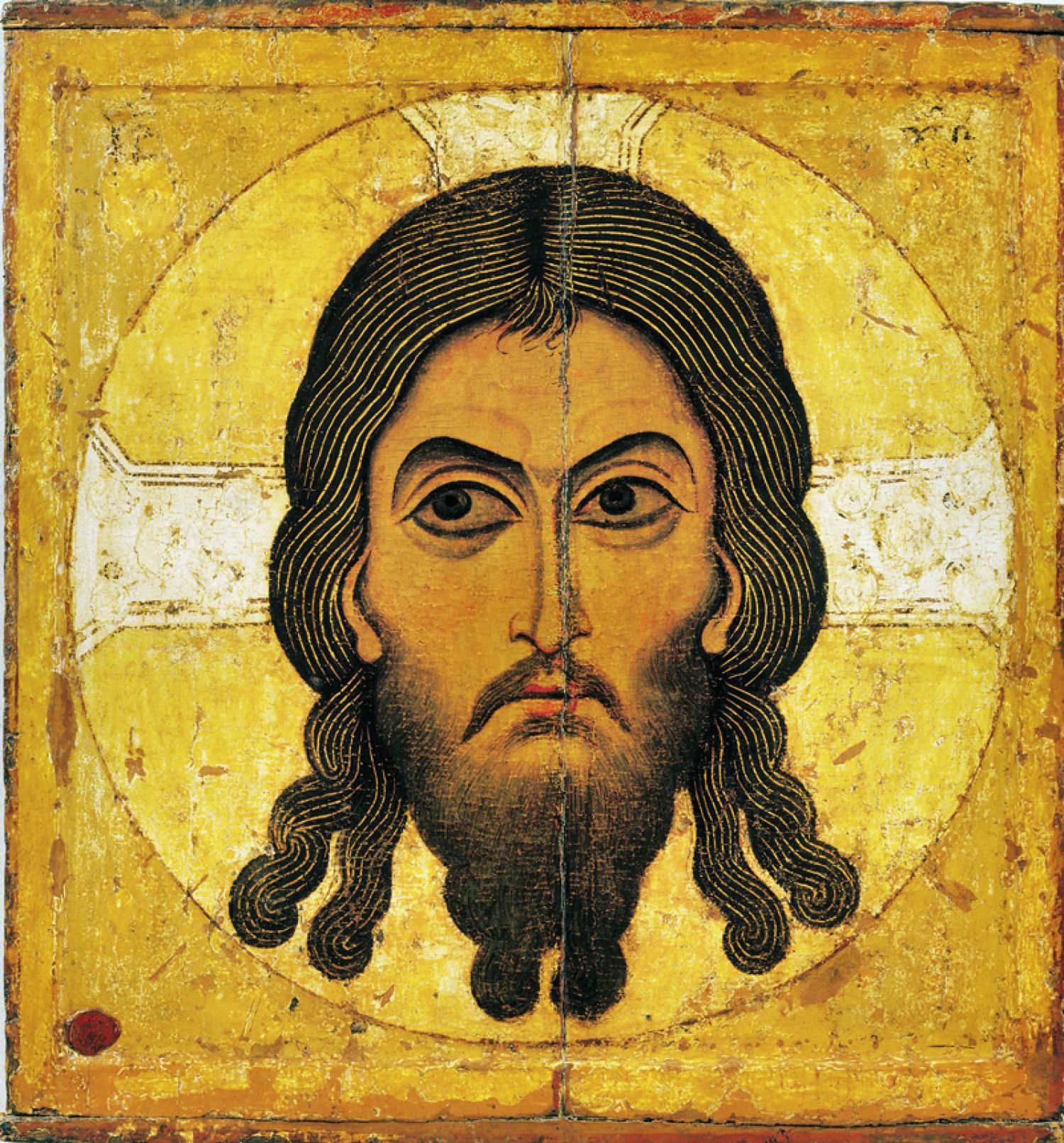

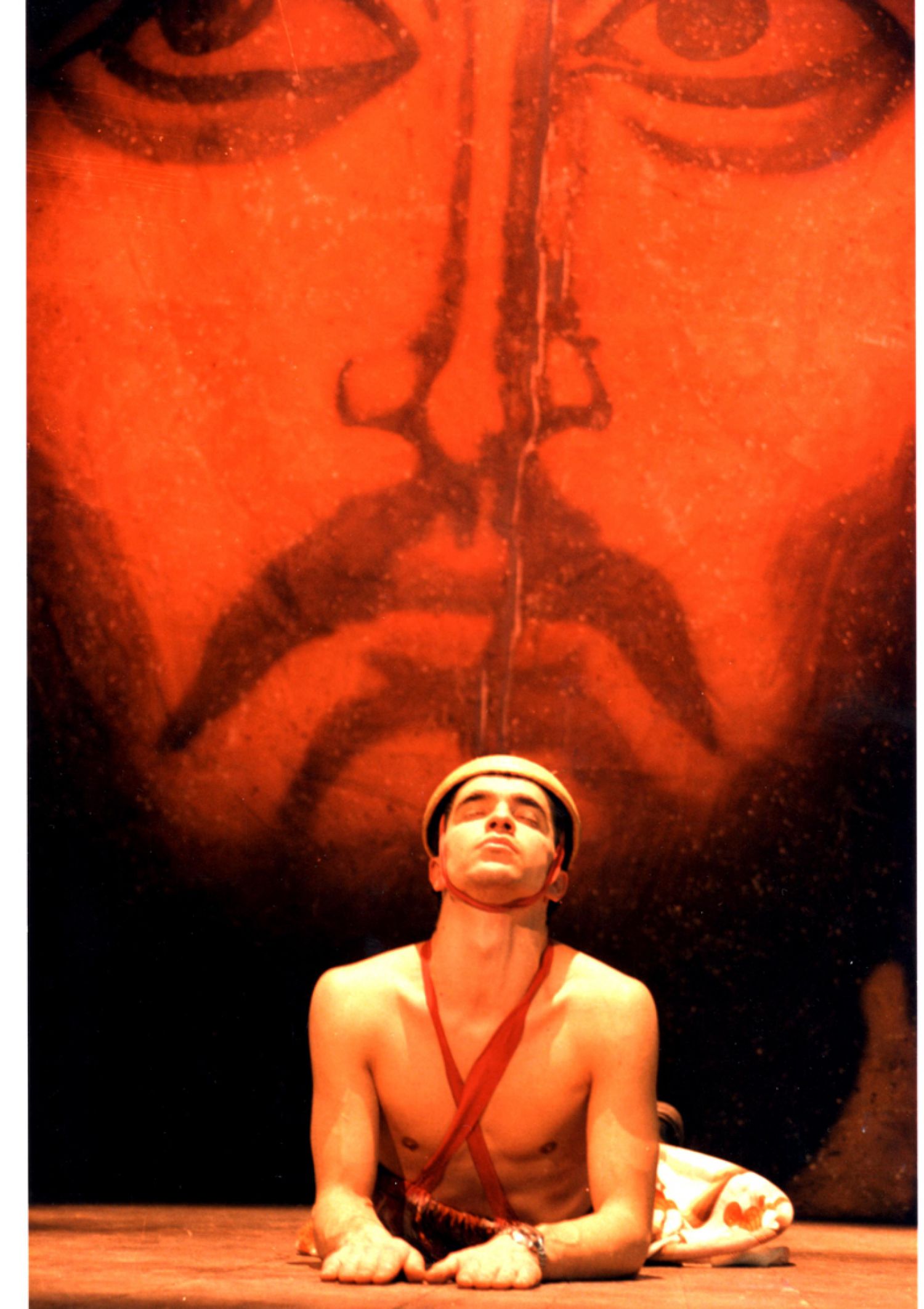

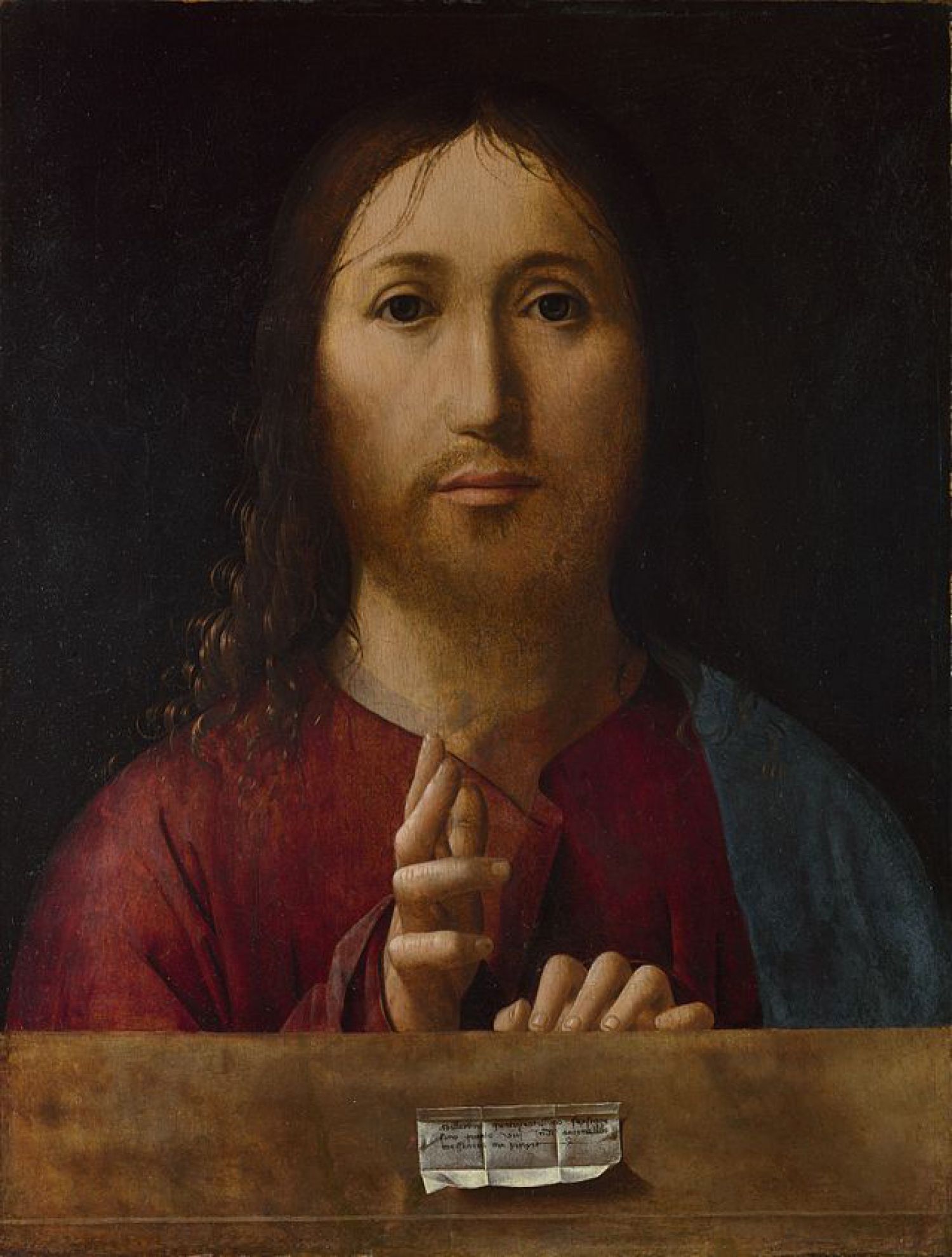

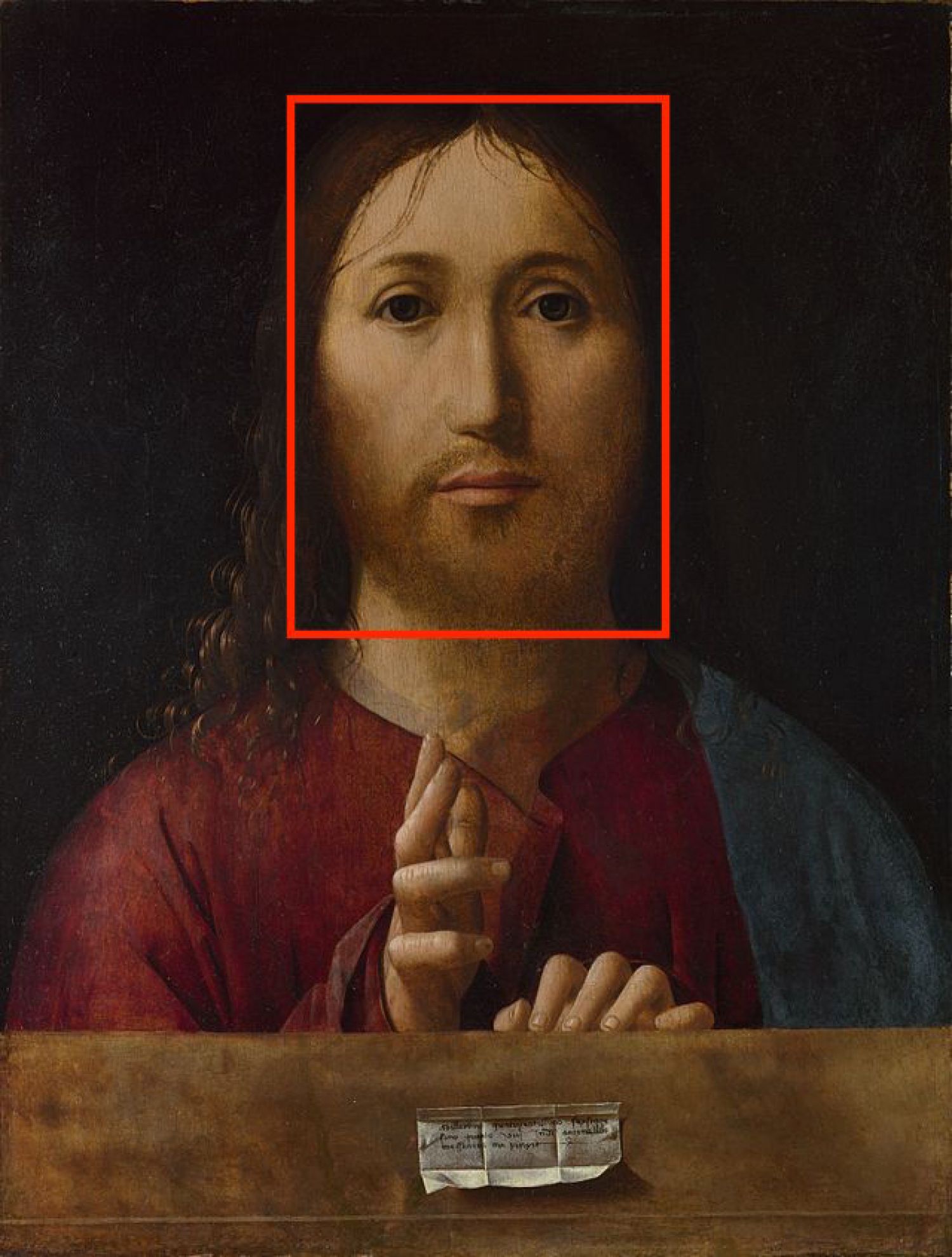

As we can see, Deleuze shortcuts the two aspects of the close-up and the face. In his text he also acknowledges the implication between these and, broadly speaking, the painted portrait, including both the modern, post-Renaissance, portrait and the earlier icon of divine persona. These aspects are clearly of interest in relation to Castellucci, as he both has included in previous shows large reproductions of known paintings - that were ostensively presented to the audience, very much as Els close-up - and he clearly did it for affective reasons. It is so that an icon of Christ played a prominent role in one of the first major shows of Romeo Castellucci and Socìetas Raffaello Sanzio, Santa Sofia. Teatro Khmer (1986; fig. 7; cf. fig. 8),[12] van Eyck's Portrait of a Man in a Red Turban (fig. 9) appears in Hey Girl! (2006; fig. 10) and da Messina's Salvatore Mundi (fig. 11) in On the Concept of the Face Regarding the Son of God (2010; fig. 12).[13] As to the reasons for these choices, for instance, here is what he says about da Messina's Salvatore:

This show precisely chose the painting by Antonello because of the gaze that the painter managed to create in the ineffable expression of Jesus’ face. [...] This gaze is directed at the gaze of each spectator. Spectators are focused on the stage, but this gaze is continuously fixed on them. This economy of the gaze addresses and challenges the conscience of every spectator and their condition as such. The Son of God, laid bare by men, is now laying us bare. This portrait by Antonello is no longer a painting, it becomes a mirror.[14]

Clearly the choice of this portrait is motivated on pathetic grounds and the gaze is identified. The choice has the highest significance as da Messina's Salvatore is an impure image, halfway between different iconographic types with rather different status, or a condensation of both. The mise-en-scène of Castellucci stresses this aspect as indeed he did not present an enlargement of the small panel at the British Museum (barely bigger than an A4), but presented a cropped version of this painting. And by cropping away the cartello and hands of the original image, he did away with elements that stress its character as a Renaissance portrait. By focusing on the face of Christ, almost symmetric, particularly flat, the other aspect emerges all the more clearly, that is to say, the aspect of a divine icon. Although there is an historic continuity between a type and the other, at a certain moment the paths forked, and it is so that, with the development of art, the older images acquired an aura of authentic images, either as imprints of the divine persona or as non-made by human hands.[15] By condensing the two types, da Messina gives a particular salience to his panel, something that Castellucci further stresses with his cropping and enlargement.

As we have seen, Castellucci identifies the gaze as particularly relevant. In fact, he also did it in relation to the lone baby of BR.#04 Brussels. Indeed, if one expands what Castellucci says about the lone child, he is also commenting on the profound impact an empty gaze can have upon the audience:

Very often there is the gaze, which I believe is an empty gaze, of the actor in front of the spectators. There is always someone who looks. In Zagreb, when we performed [BR.#04 Brussels], it was beautiful. The baby was magical...[16]

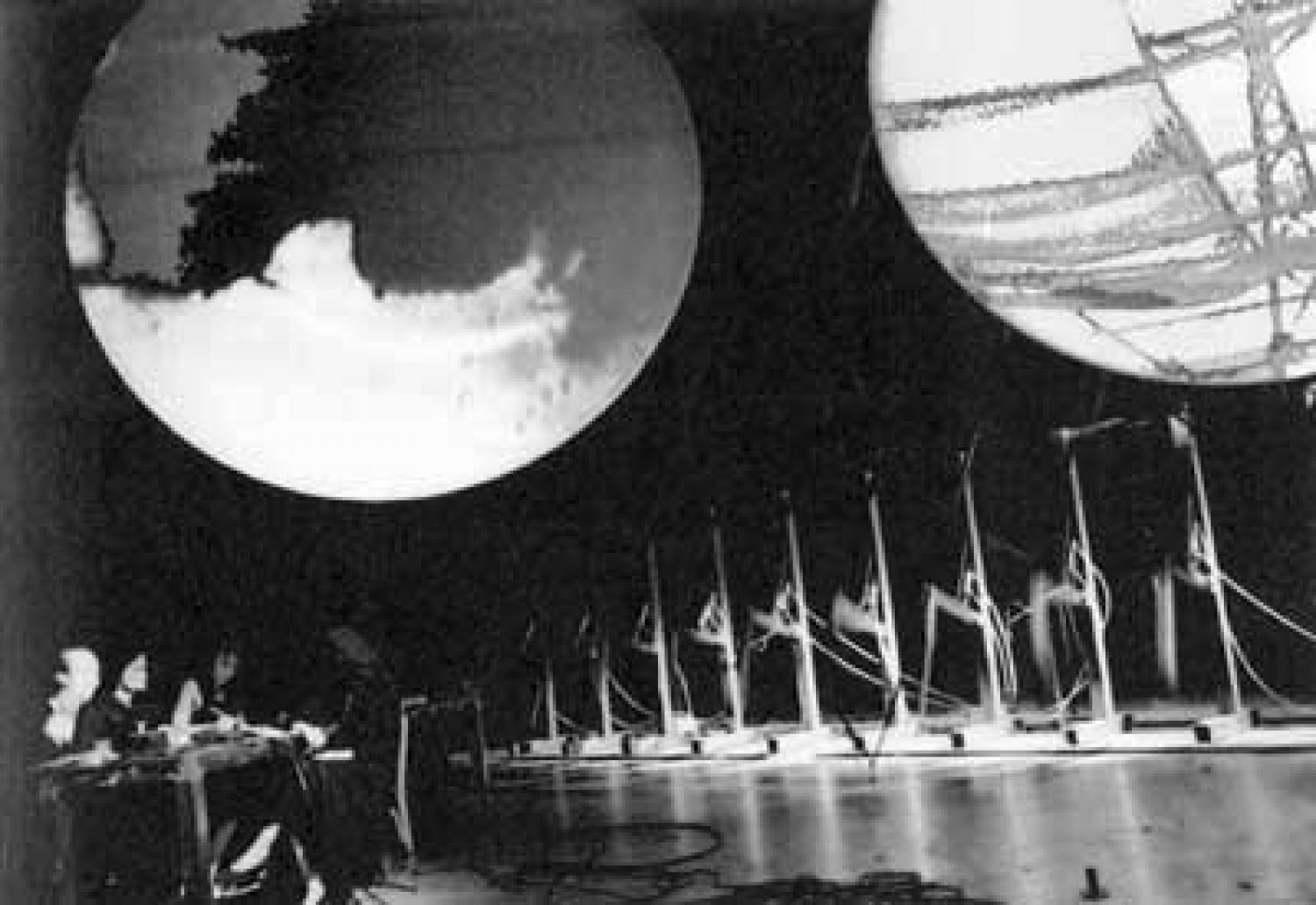

Besides these gazes, at the end of La Passione, the narrator, Ian Bostridge, approaches the audience, looks at them and exhibits a mask that will be left there staring, while he leaves (fig. 13); in L.#09 London (2003) a Dionysian prosopon stares us from the stage (fig. 14);[17] in Voyage au bout de la nuit (1999),[18] it was a pair of eyes, placed above the stage, that stared at the audience, as two round screens onto which were projected violent images of war, pornographic footage and the superimposition of portraits (fig. 15), in the manner of Francis Galton’s composite photos. More recently, at the overture of the Tannhäuser (2017), a huge eye was projected onto the screen at the back of the stage (fig. 16).

There is, of course, the recurrence of the same motives, but what is more, in his justification on the choice of da Messina, Castellucci clearly acknowledges the economy that is so specific to these gazes that stare at us. Though emanating from man made, lifeless, constructions, for a moment they stare at us, they acquire a capacity that is ours, and this questions us. Let us recall: «This economy of the gaze addresses and challenges the conscience of every spectator and their condition as such».

This is an effect well-known to ancient Greek culture, named apostrophè. It is an exception in this culture where the rule was frontal representation and face-to-face interaction (that we perceive as representation in profile), as – in order to make it short – being alive was seeing and been seen.[19] The gaze that escapes this strict order, staring he beholder, the gaze that addresses our gaze, is indeed an exception. Françoise Frontisi-Ducroux has stressed the importance of the apostrophe, that namely holds a prominent place at the banquet, as a device critical to the constitution of the person as an individual and a social being.[20] It is not idle to mention these apparently anachronistic aspects in relation to Castellucci as, on one hand, he is obsessed with the portrait, the gaze, a prosopon made its way to the stage on the occasion of L.#09 London, and, on the other hand, his quest in this direction is a quest in desalienating the spectator from spectacular domination.

The portrait and gaze of Els have a cinematographic nature in an opera show, are reminiscent of the portrait and prosopon. It is neither simply nor only the gaze of a bedridden person.

«Images suffer from reminiscences», thus said Freud about the symptoms of his patients. About the same time, Warburg could observe the same in relation to artistic images. For instance, that the farewell angel in a bas-relief of Agostino di Duccio (fig. 17), was directly inspired by the life threatening ancient Maenad; or that the eroticised Ninfa fiorentina, borrowed from Ancient representations of mourning; in this case with a shift from funerary to erotic pathos.

Images at once are reminiscent and suffer, convey pathos – the portraits of Castellucci, particularly that of Els, make this plainly visible.

Footnotes

- ^ In parallel Romeo Castellucci created two similar stagings for the two musical versions of the same tragedy, that would premiere in Vienna and Brussels only one month apart from each other. I shall comment on the Brussels production, which I saw. For a description of the Vienna production, and how it differed from the Brussels’ one, cf. the fine description and analysis in N. Ridout, «I vivi e i morti. La solitudine in relazione», in P. Di Matteo (ed.), Toccare il reale, Napoles, Cronopio, 2015.

- ^ All quotes from the libretto are from C. W. Gluck, et al., Orphée et Eurydice. Libretto, Brussels, La Monnaie / De Munt, 2014, and, for the English translations, from C. W. Gluck, Orpheus, Charles D. Koppel Publ., date unknown (at http://hdl.handle.net/1802/14204, aug. 2017

- ^ N. Ridout, «I vivi e i morti. La solitudine in relazione», op. cit., p. 113: «Il flusso dell'allestimento innesca una sottocorrente emotiva sbalorditiva».

- ^ D. Semenowicz, The Theatre of Romeo Castellucci and Socìetas Raffaello Sanzio, trans. P. Cichon-Zielinska, New York, Palgrave Macmillan, 2016, p. 199.

- ^ Ibid., p. 201.

- ^ For a more articulate argument, considering a larger array of aspects and determinations, see my Laissez-vous toucher... A portrait by Romeo Castellucci, Lisbon, KKYM, 2017, in print.

- ^ Presented in Lisbon in 2006.

- ^ Cf. C., R. Castellucci and C. Guidi, Epopea della polvere, Milan, Ubulibri, 2001, p. 185, and W. Shakespeare, Julius Caesar, in The Complete Works, ed. S. Wells and G. Taylor, Oxford, Oxford Univ. Press, 1988 (1998), p. 616.

- ^ Presented in Porto in 2017.

- ^ C. and R. Castellucci, et al., The Theatre of Socìetas Raffaello Sanzio, Abingdon, Routledge, 2007, p. 209 - slightly modified.

- ^ G. Deleuze, L’Image-mouvement, Paris, Minuit, 1983 p. 126 [The Movement-Image, trans. H. Tomlinson and B. Habberjam, Minneapolis, Univ. of Minnesota Press, 1997, p. 88].

- ^ In C. and R. Castellucci, Il Teatro della Societas Raffaello Sanzio. Dal teatro iconoclasta alla super-icona, Milan, Ubulibri, 1992, p. 28 it reads «the face of Our Lord Jesus Christ, from an acheiropoietos icon from Novgorod», therefore a likely reproduction of fig. 8.

- ^ Presented in Lisbon and Porto in 2016.

- ^ R. Castellucci, in an open letter published in Corriere di Bologna, 17.1.2012 (at http://boblog.corrieredibologna.corriere.it/ 2012/01/17/romeo_castellucci_interviene_s/, Aug. 2016).

- ^ H. Belting, Likeness and Presence, trans. E. Jephcott, Chicago, Chicago University Press, 1994, p. 210.

- ^ See note 10, above.

- ^ Cf. S. R. Sanzio, «From the final script of L.#09», in C. and R. Castellucci, et al., The Theatre of Socìetas Raffaello Sanzio, op. cit., p. 166. Cf. also p. 207.

- ^ Presented in Lisbon in 2002.

- ^ F. Frontisi-Ducroux, Du Masque au visage. Une figure du Dionysos d'Athènes, Paris, Découverte, and Rome, École française de Rome, 1991, where in p. 46 it reads: «The face is considered by the Greek as a privileged medium of relation between individuals».

- ^ According to Frontisi-Ducroux, the relation that is established between image and banqueter is a relation with an-other, and is quite meaningful: «The encounter with another self [autre soi-même], on the cups where it is played out, as a counterpoint to the visual and verbal exchanges between companions, that sublime alternation between face and profile, was the opportunity for a far more intimate and direct contact with the prosopon than the distant face-to-face with the tragic masks that resurrected on stage the heroes of yesteryear» (ibid., p. 216). These eyes turn a vase into a face, a prosopon, faces that ass from hand to hand, are exchanged, becoming instruments of conviviality and sociability within those practices of identity confirmation – masculine and civic – that are at the core of the Greek banquet: «A collective confirmation repeated throughout life, as Plato clarifies in the Laws, where he regulates on and justifies the use of wine (Plato, Laws, 649d-650b, as quoted in F. Frontisi-Ducroux, Du Masque au visage, op. cit., p. 317, note 22). The collective consumption of this liberating beverage, he says, offers the occasion and the means for testing oneself and the others. It was a test of one’s virtue, courage, resistance and self-control. […] The necessary utensils to contain the wine and from which it was consumed play a role to this experiment. They take part in it as actors or characters, containers that are passed around and are able to say I, containers painted or modelled as faces, prosopon of oneself and the other: their role is not so different from that of the masks wore by the young Spartan on their rites of passage, as a means to explore different figures of otherness [étrangeté] before conforming to the proper model and becoming like their elders, the Homoi, the ‘similar’» (F. Frontisi-Ducroux, Du Masque au visage, op. cit., p. 224).