Pancho Guedes, the memory of a collector

Natasha Guedes

Matter never makes jokes: it is always full of the tragically serious. Who dares to think that you can play with matter, that you can shape it for a joke, that the joke will not be built in, will not eat into it like fate, like destiny? Can you imagine the pain, the dull imprisoned suffering, hewn into the matter of that dummy which does not know why it must be what it is, why it must remain in that forcibly imposed form which is no more than a parody? Do you understand the power of form, of expression, of pretense, the arbitrary tyranny imposed on a helpless block, and ruling it like its own, tyrannical, despotic soul? – Bruno Schulz, The Street of Crocodiles, 1934, pg. 64

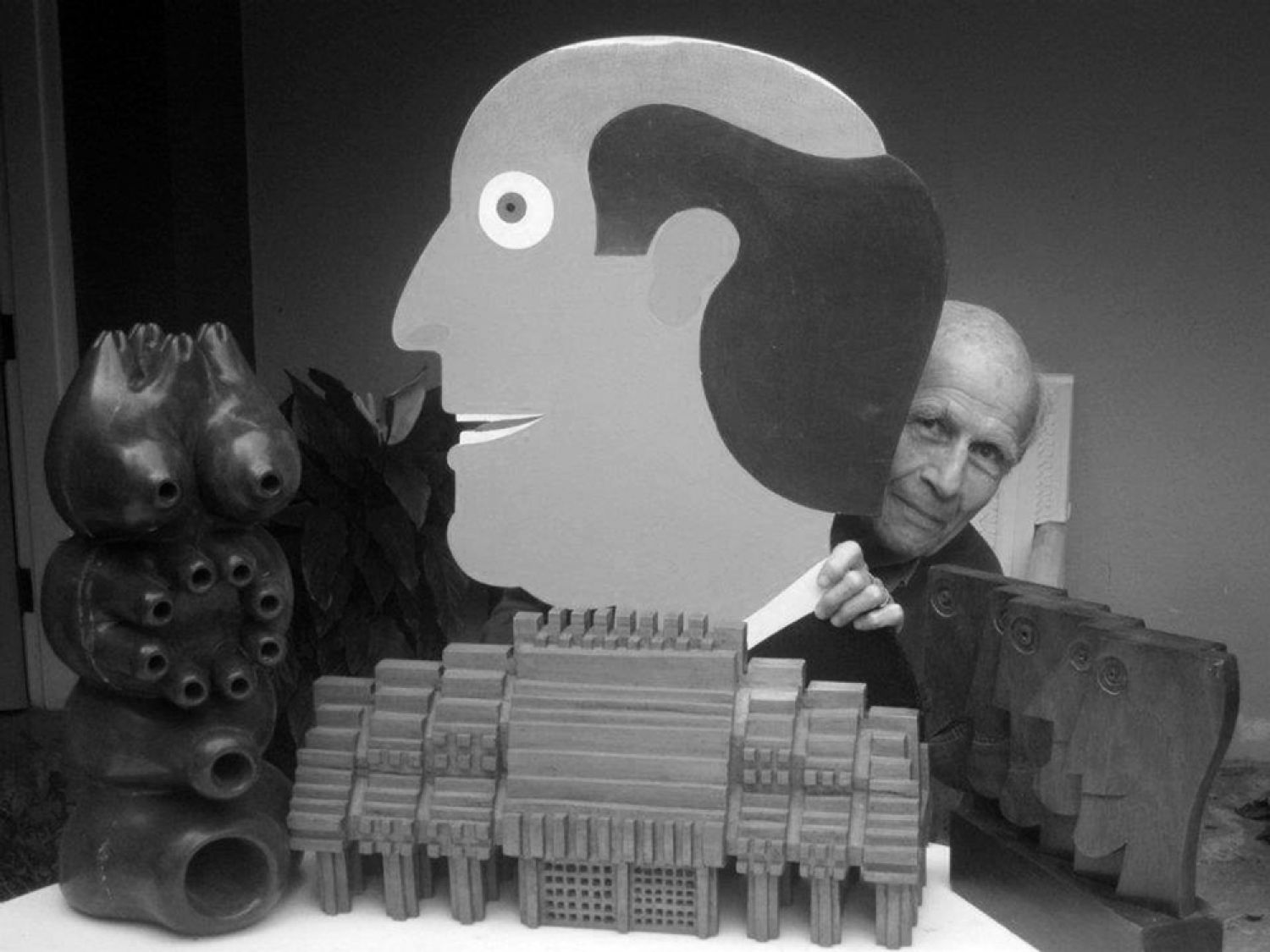

The house smelt of damp concrete, dust and tea. There was not an empty space on the walls and rarely an empty space on the floor. A parade of wooden animals hurried down the stairs, phallic sculptures in the guise of trains, boats and dollhouses emerged startlingly from the walls, and a whole plethora of wild, violent and colorful paintings melded into its own vibrating mass of a beast - a beast that told stories.

Every nook and cranny was stuffed to the brim. -Wooden dolls with odd shapes and faces; terrifying masks that stared provokingly at you; pieces of gravestone and wooden crosses, that once marked someone’s resting place in the African desert, now serving as a kind of decorative piece amongst other grave markers on the wall; a statue of St Agatha pillaged from a church somewhere, her titties placed on a platter (my grandfather used to say that they were meringues); a wooden crocodile crouching underneath the sofa ready to nibble at guest’s heels, or a fantastic two headed monster posing as a sewing basket…

This place was both terrifying and fascinating. We were back to the connoisseurs’s Wunderkammer of prestige. A collector who amasses objects as a sign of wealth and importance becomes a collector who defines himself by his objects. My grandfather would walk through his house; his hands clasped neatly behind his back, a little lord Fauntleroy walking amongst his toys.

Amâncio Guedes was born in 1925 in Lisbon, but grew up, mostly, in Mozambique. His father, a doctor, wanted to work in the colonies, not far from his brother in law who was a Salazar deportee. Pancho (Amâncio) decided to become an artist/painter after he finished school but his parents disagreed and encouraged him to study architecture instead. He was initially horrified by the idea, but soon realized that architecture was as liberating as art so he went to South Africa to study at Witwatersrand.

My father and my grandfather both grew up in an Africa that no longer exists. But they were both painfully a part of this Africa, that has now so rightly disappeared and left behind it’s lost and uprooted orphans.

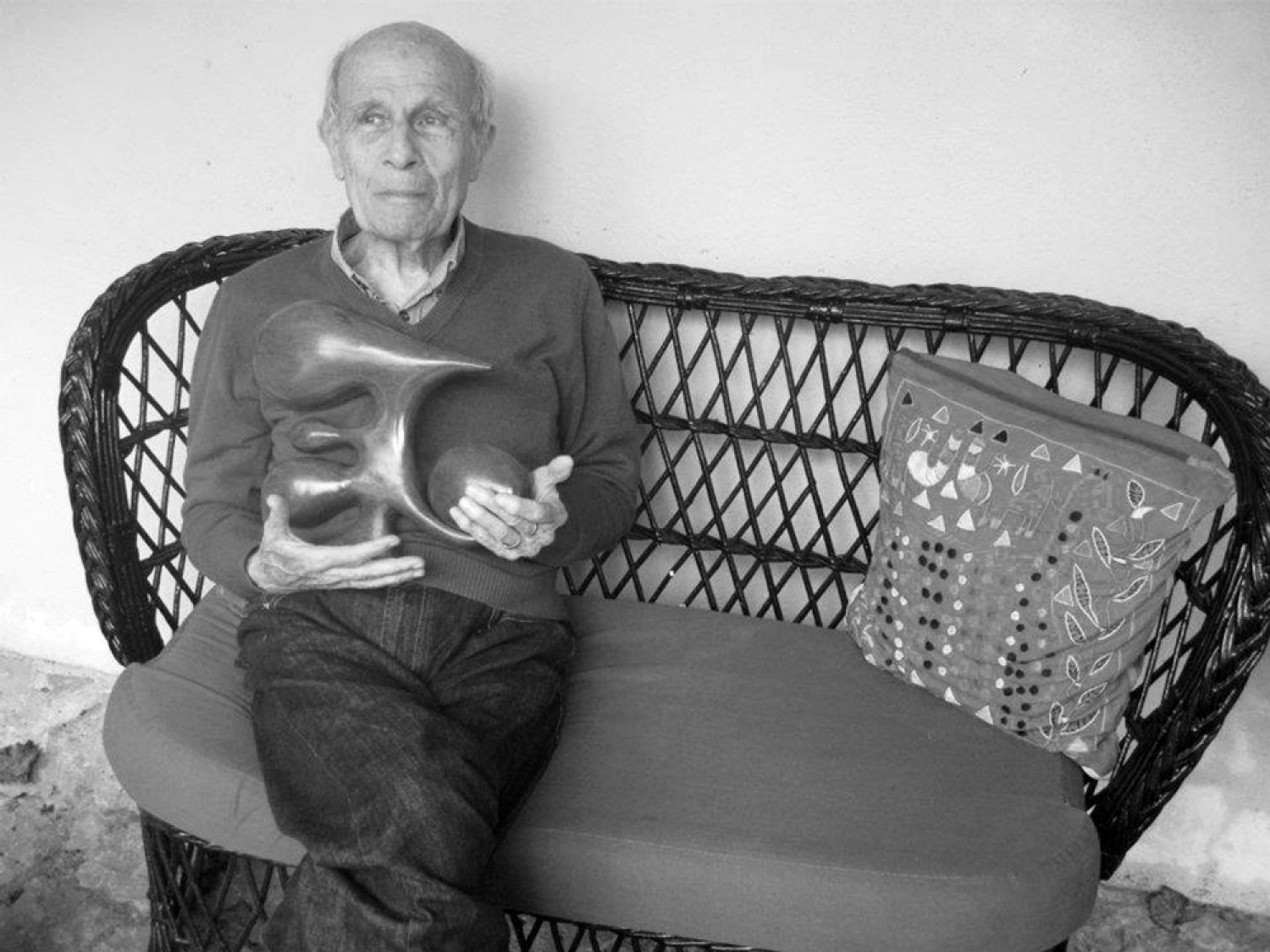

Pancho was an architect, an artist and a patron of African art, but he was to me a collector of objects. Why does the collector collect? Is it this urge to preserve something that might be lost without him? To amass and bring associations of things together, which others wouldn’t necessarily see unless he associated them. Is there not something profoundly narcissistic in the whole concept of collecting? Is it too obvious to say it is about filling the void, re-finding the lost object or at least replacing it? We can find our way back to Freud with his lost object that can only be replaced with a found object. The child missing its mother’s breast which finds language as a substitute. But is that really always the case? Could collecting be in some sense a cover up? A way to hide behind all the objects and a way to hide oneself? Or simply not deal with oneself?

My grandparents were not big and unnecessary spenders. They lived rather humbly and were as far as I recall cautious and careful with their money. His big pride was his Citroen ‘2 cavalos’ that clattered up and down the dangerously winding road that led to their ‘top house’ near Colares. Money was meant to be spent only on certain things – art was a big part of that.

What was it inside these objects that so attracted my Grandfather? His collection was incredibly eclectic and didn’t only encompass African art, but also religious/sacred art, art nouveau and art deco pieces, children’s drawings, doodles… to name a few things. There is certainly a great value in this amass of objects but some are also worthless. My grandfather was obviously deeply attracted to the art itself and had a great passion for it. Every object was carefully chosen, the relations between the objects themselves were not always apparent. It didn’t seem to have been Pancho who built the space they were in but rather the objects themselves that built and shaped it.

Bruno Schulz wrote: ‘there is no dead matter, lifelessness is only a disguise behind which hide unknown forms of life. The range of these forms is infinite and their shades and nuances limitless.’ (Bruno Schulz, The Street of Crocodiles. pg. 59-60)

There was much inside those objects; whether it be the terrifying lifelike Maconde masks and dolls used in initiation ceremonies or as caricatures that were given to him or purchased (one was even made by prisoners for him), the grave markers that my grandfather fetched himself from an abandoned cemetery for slaves in the desert in Angola, the Lomwe initiation masks that were used for a gruesome coming of age ceremony that Pancho documented (these masks were often discarded after their use and my grandfather asked for some to be put aside for him.)

Was it the objects themselves that called out to him? Pancho spoke of buildings as living beings. You could not visit a city with him without its walls coming alive. The houses were either dancing down the street, or cathedrals were looking disapprovingly at pompous churches, parading themselves in a rather vulgar fashion.

The interior of his house was brewing with its own life. All these objects that once had a past and a memory filled the house with heaviness. It was hard to think in there. There were so many stories wanting to be told – but maybe for those who knew the stories there was no longer any ‘noise’ coming from the objects themselves. Perhaps once they had told their story they become quiet and humble.

I wonder who remembers these stories. I myself know very few of them.

According to Alexandre Pomar 'the objects he (Pancho) collected, as he himself has stated, helped him free himself, ‘from the dominant Eurocentric view of the white man who lives in the lands of others.'[1]

My grandfather sneered at European values of what should and should not be considered art and how art should look. He argued that African art was as valuable, creative and vibrant as its European counterparts. For Pancho, all African art was tribal or folk, including that of the Portuguese colonialists living there at the time. It is an interesting view and very much in line with his other view that a good artist needs not to be ‘educated’: particularly not in the European tradition. He believed that the over education of an artist and over exposure take him away from his roots and therefore away from his capacity to bring out what he really is and what he really has inside of him.

My grandfather’s collection was as much a part of him as his own work. He had so carefully chosen those objects, amongst masses of tourist produce at markets on his many journeys around the African continent. He also cultivated young African artists and craftsmen with whom he surrounded himself. That he did a great deal to encourage and support young artists and craftsmen is a certainty.

Many of Malangatana’s paintings, from my grandfather’s early collection, have been exhibited around the world, including in the Tate modern, in London and I believe at the Pompidou, in Paris. A lot of the other contemporary African artists are less well known. Their work never reached the international prestige that Malangatana had, which paved the way for many other African artists at the time. Tito Zingo’s ‘written’ drawings were most exceptional – framed with carefully made wooden frames that my grandfather had made especially almost as a continuation of Zingo’s own work with airplanes and houses – along with paintings by Portuguese artists living in the country at the time, such as the brightly coloured paintings by Rosa Passos or the strange universe of António Quadros.

Craftsmen and local artist would gather in his work office/studio in Mozambique and he would encourage them to create embroideries out of their drawings or out of children’s drawings (a great passion Pancho had was collecting children’s drawings). He has in his collection those made by Pedro Josefa Menge. My own father has a few of his drawing of cowboys in gun battle turned into cushions.

This African art exhibition was put on display at the Feira da Ladra exhibition space in Lisbon. The artwork removed from the house and placed on display seemed enormously out of context and cold, in comparison to the very eclectic mix of objects at his own house. There is still a large deal of South American art and religious art or even art nouveau or art deco pieces that have never been put on display. It is difficult to catalogue them or even realize the scale of all those objects that he so carefully selected to share his home with. Those objects were his living companions and in some ways could be called his other family.

‘Can you understand,’ asked my father, ‘the deep meaning of that weakness, that passion for colored tissue, for papier-mâché, for distemper, for oakum and sawdust? This is,’ he continued with a pained smile, ‘the proof of our love for matter as such, for its fluffiness or porosity, for its unique mystical consistency. Demiurge, that great master and artist, made matter invisible, made it disappear under the surface of life. We, on the contrary, love it’s creaking, its resistance, its clumsiness. We like to see behind each gesture, behind each move, its inertia, its heavy effort, its bearlike awkwardness.’

Bibliography

Bruno SCHULZ, The Street of Crocodiles. New York: Viking Penguin Inc., 1977 (from original text published in Polish in 1934).

Alexandre POMAR, «An African collection» in As Áfricas de Pancho Guedes: Colecção Dori e Pancho Guedes. Lisbon: Câmara Municipal de Lisboa, 2010.

Pancho Guedes Vitruvius Mozambicanus. Lisbon: Museo Colecção Berardo, 2009.

Footnotes

- ^ Alexandre POMAR, As Áfricas de Pancho Guedes: Colecção Dori e Pancho Guedes. Lisbon: Câmara Municipal de Lisboa, 2010, p. 9.