Notes from the labyrinth or the infinite web

Filipa Cordeiro

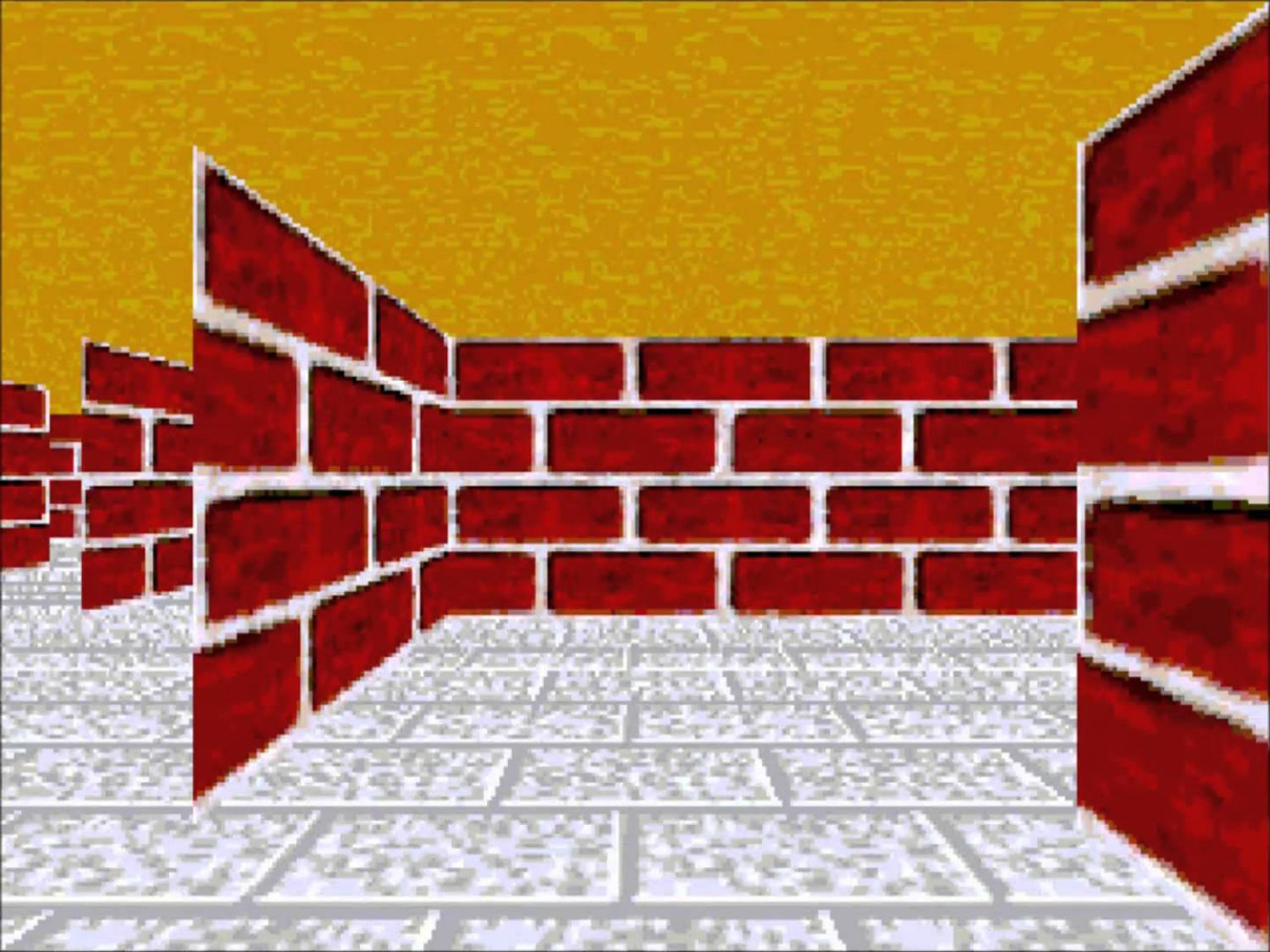

In a celebrated Windows 95 screensaver, the user (represented by a subjective point of view) could wander through a 3D labyrinth with brick walls, enclosed from above and bellow. After entering the labyrinth, there was no end or slit to ease the suffocating atmosphere that was felt in the heart of the digital crypt. The scene recalled a pharaonic chamber, and the labyrinth was, for many, the strange and synthetic representation of the essence of the operating system. Can this metaphor still be effectively applied to navigation in the age of the web? The answer is yes, if we have in mind the movement of everlasting roaming that characterizes it, which still inscribes in it a peculiar experience of infinity. However, unlike the first labyrinth, the labyrinth of the web is characterized by its porosity: an essentially open quality, which has long transposed the limits of the digital. These notes result from a non-disinterested observation of that reality.

1.

The proponents of «digital dualism»[1] tend to ascribe more reality to what goes on outside the computer or smartphone screen than to what takes place inside it. Such a claim presupposes an ontology that ascribes more being to what is offline than it does to what is online. In order for it to be consistent, its proponents must be able to prove its underlying assumptions. But if the question of ontology is brought back to the ones that inevitably pose it (human beings), we can but consider it as an enunciation of the modalities of being of a surrounding world that is essentially relevant to humans. It is, thus, futile to think offline and online realities apart from those to whom they are constituted. From a purely positivist standpoint, both «physical» and «virtual» activities are nothing but states of affairs that follow one another. Ultimately, the interaction that takes place inside the screen is nothing more than a succession of code combinations rooted in a medium that is just as physical as any other.

In order to reveal such a difference, one must focus instead on the user, as one might say[2], to whom there is never such a thing as a purely positivist standpoint. Far from relating objectively to a world of heterogeneous elements, as a researcher would, the user charts these elements (whether physical or virtual) primarily as eligible to integrate actualizable possibilities of his existence. In other words, humans use what surrounds them as a means of self-actualization[3], and Internet use is part of this framework of possibilities, alongside much older activities. Surfing the web is, thus, one more possible way of existing – a recent possibility that has, to be sure, created new frameworks of meaning in light of which human beings must now interpret and shape their existences[4]. So it makes no sense to think of an ontological difference between the physical and the virtual, and «digital dualism» is thus reduced to a moral notion that condemns the digital based on metaphysical assumptions. Nevertheless, it is possible to consider, inside of the same framework of reality – the common domain in which humans breathe, work and live aesthetic and political experiences –, just how are such modes of relationship configured in the present, when they take place additionally in digital platforms, which interact in an increasingly permeable fashion with the activities that take place outside them[5].

2.

We now proceed to a hypothetical near future: Facebook completes its transformation into a counting tool and competes with the civil register, and therefore with the State, for the monopoly of information. In its database, it is possible to observe the cultural preferences and social behaviours of an extended social fabric[6]. It is a voluntary-registration database, yet already naturalized, in order to ensure in advance that each citizen is delivered to his own personal marketing technician. Registration at birth enables the ideal customization of displayed contents, finally leading to a perfect symbiosis in which the user is produced by the network, the network produced by the user[7]. The marketing technician is already an algorithm: a shadowy figure crowned by the odd dignity that stems from belonging to the domain of mathematical truths, of being a truth that processes or a process for producing truth. Through market research algorithms consumers are generated. Therefore, in the age of widespread commercial registry, each human being is a citizen, each citizen a consumer. That is, after all, what the largest social network of the moment is all about[8] – massive harvest of data that has been voluntarily released by users through their choices and usage patterns, which serves the creation of comprehensive consumption profiles, later sold to the most suitable potential advertisers. The social relations that take place in Facebook are undoubtedly real and serve, in their concreteness, the production of economic wealth through an inconspicuous process that is, after all, what motivates the existence of the social network in the first place.

The structure of network socialization arises from a commercial exploratory impetus – but that does not mean one should overlook its practical significance. A user that was born in 2000 is different from a user born in 1950. Which boundaries define a cybernetically atavic brain? One could think that these boundaries are not related to age, depending only on network usage patterns. However, those who were born into a post-internet world have a different thought structure than those who were born before its existence, since their processes of learning languages and modes of being already took place within a dominant cyber culture[9]. Between these two extremes (1950, 2000) we find one or two generations of children of the transition period (1980). Are there, among them, those who wish to attain a state of cybernetic atavism, neo-Luddites of the post-internet age? The quest for unlearning post-internet thought structures is as complex as the quest for unlearning a mother language. In this near future, when these three generations still coexist, one can image that there are minds maladapted to the general way of thinking, which will inevitably incur in misunderstandings of communicational decoding. Stuck outside the network-mind, they won’t be able but to reconstitute abstruse and obscene messages with their archaic technology, and they will perhaps speak a language turned into poetry or, if you will, the babbles of a proscribed species.

3.

The system sleeps, the screen goes off and shows the user his own reflected image in the black mirror surface. The excess of sugar causes nightmares: a lesson of adolescent love, which cultivated nights of poor sleep like hard-earned medals. In the heart of sleepless nights, one had to go through the mazes of the mind, pervaded by the glow of the screen, whose alternating lights inscribed the codes of the structures of the infinite web into the brains of the argonauts. One looked for easter eggs in operating systems and learned visual and linguistic rhythms, never to be forgotten. Is such an exploration still possible? Some critics advocate the twilight of poetry made from everyday images, they denounce fifty beat poets for each true hero, one hundred and twenty poems for or about William S. Burroughs for each electronic dissident, grapes harvested by too many wraths.

Which way is there left, then?

Fallowing, naturally. Winters are still cold, window frames still made of aluminium, the breeze still of death, the butcher still sleeping, in an afternoon still hot, still the flies, still the flesh. From time to time Portuguese crowberries (corema album) are still found, rare translucent white berries, along certain maritime slopes. They unveil themselves before those who roam the coves amid the low shrubs, perhaps finding, in the distance, when the hike is already long, a foreign fisherman with dark skin, a blue sweater and a red beanie. Solitude or community? One hears a word in another language: yes, a word, one identifies that as the belongings and the meaning of someone else, and not as just some noise. Despite the silence, we feel part of a community of thinkers.

Footnotes

- ^ This expression has been used by Nathan Jurgenson, creator of the blog Cyborgology, to designate the more or less expressed viewpoint that opposes the «reality» of the physical world to the «virtuality» of web interaction. This conception supports the critique of social network by way of considering it a modality of virtual social interaction, which is, thus, disparaged – as unreal, estranged and essentially separate from what takes place outside the screen.

- ^ As we will see, this designation, casually used in the Internet (for instance in the term username) can be just as useful in the offline scope.

- ^ No moral judgement ascribing a utilitarian essence to a supposed «human nature» is intended by this expression. It means, instead, to underline the essential existential importance that all elements of experience hold for humans – which means that these elements are met from a relational point of view – as things that can be used or that can affect me: in short, with which I relate as a means to conduct my existence, and not as existentially indifferent elements that appear to a disinterested observer who may, optionally, get involved with them. (See in this respect the 1st Division of Martin Heidegger’s Being and Time).

- ^ It should be noted that the ontology proposed by Heidegger acknowledges the essentially dynamic way in which being is given. The basic condition of human existence – the fact that humans have to lead their existence by way of relations to that which surrounds them – takes form differently in time.

- ^ This is also Nathan Jurgenson’s thesis, who argues that the use of apps like Foursquare conditions user’s movements, while Facebook use is part of an individual’s identity, be it through the «photogenic» experience of daily events with image-sharing in mind (which inscribes the preoccupation with self-representation in daily life), be it through the time spent in online interaction, which is no less real than that spent in other activities.

- ^ In a social network like Facebook, the range of possible social behaviours is limited to the options built in the system (customization fields, user-interaction options, etc), which all take place inside the same relatively closed system. This interaction is already different from pre-Facebook web use, which had a greater exploratory quality that allowed users greater freedom.

- ^ Do these propositions ultimately come to the circular idea that the network produces itself?

- ^ It is hasty to assume that Facebook will still be ubiquitous in the near future. The danger of social network obsolescence, well exemplified by the desertion of MySpace for Facebook, isn’t less palpable than that which impends in the case of digital formats. In both cases, an unavoidable loss of data ensues. It thus can happen that a significant amount of data essential to the very identity of users can become «captive outside them».

- ^ A sound bite by Google chairman Eric Schmidt comes to mind here. Schmidt declared that the future of the Internet is to «disappear» – that is, to become part of every aspect of life to an extent that its presence becomes invisible to the human eye. In fact, the ultimate form of presence of something is its omnipresence in the mode of presupposition – which renders that same thing nearly impossible to be evaluated or questioned, since it becomes part of the natural point of view, that is, the basic framework that allows questions to be made about everything else.