Michelangelo Pistoletto: Time Rooms

Cristina TerzoniThe different repetition

This is a reflection on part of the theoretic and artistic writings by Michelangelo Pistoletto (Biella 1933), who lives and works in Turin. An exponent of Arte Povera, Pistoletto began his career as a painter, later moving on to the recovery of poor materials. His activity from the second half of the sixties on, when his work starts to include human figures, is especially interesting to us. Pistoletto's mirror installations in rooms, in 1975-76, question the several possible realities created by the polished surfaces' reflections and question the viewer on his infinite latent personalities.

This brief essay relates the theoretical writings by Pistoletto with the text L’instauration du Tableau, a study on the evolution of Flemish art in the 17th century by historian and art critic Victor Stoichita (Bucharest, 1949). It focus on the cyclic occurrence of parallelisms between Pistoletto's art and the work by the artists considered by Stoichita in his 1989 book.

On the basis of the «temporal journey» what we propose is the idea of a quasi-constant law in the life of the arts: once an extreme is reached, a countervailing movement is triggered in the opposite direction. Therefore, an «explosive peak» originates an equal and contrary «implosion», a race «back» to pursue its own origins and history. The path won't always unfold forward: at one point it enters a circular rhythm, in a spiral course, one of return. Our temporal journey summons the possibility of time travelling and parallel universes proposed by quantum physics. A possibility that Pistoletto seems to have internalized and merged with a different type of travel, an inner one, on a quest for identity that, in his case, began when he was a 14-year-old.

On the fith exhibition of Le Stanze (The Rooms), Pistoletto speaks of a «missile flashing through the interstellar void», explaining that «each exhibition materializes similarly to a gas jet, followed by a second, and a third, and so on, in order to propel the vehicle.»[1] The exhibition as vehicle, not only artistic and expository, but temporal as well, a missile that leads to a timeless travel, loaded with reflection on the individual identity and the desire for a new humanism.

Theorizing his work, Pistoletto cites the mirror as an essential element. The mirror is an open portal in time because, as he explains: «it transports me in the future showing me the past. In fact, it shows me that I have a limited space, for my frontal perspective is limited, but it doesn't just project me on a single, traditional perspective (...) the mirror is bidirectional: it shows me what lies ahead and what's behind.»[2] The doorway-mirror is therefore an instrument that doubles the perspective, opening the possibility to pass in both directions.

This text is an attempt of crossing the pistolettian mirror and travelling between various historical presents: those of Michelangelo Pistoletto (at different stages), Victor Stoichita, and the 17th century Holland. With the theories of quantum physics in dialogue with the proposed concepts, to justify a physically impossible trip.

1989 Victor Stoichita

In 1989 Victor Stoichita writes L’Instauration du tableau, an analysis of painting works, mainly Flemish, from 1522 to 1675. These two dates correspond to the iconoclastic revolt of Wittenberg and to the completion of The Reverse of a Framed Painting by Cornelis Norbertus Gijsbrechts, which symbolize the death of the old conception of the image and the birth of a new one, created from an exhaustion of reflections on art and its possibilities. In Stoichita's complex discourse, self-referentiality, which plays a most important role, is itself a reflection of the specular element's integration.

1524 Parmigianino

To understand how Parmigianino achieved his Self-Portrait at the Mirror, we'll visit one other work, of 1646: Johannes Gumpp's self-portrait, in which the painter represents himself, his back turned to us, working on his self-portrait, while looking at himself in the mirror. Gumpp's meta-painting may be the explanation-revelation of Parmigianino's work.

In Parmigianino the observer is placed in front of the artist but on the other side of the mirror, as if he was looking through a window connecting two different worlds. However, while the observer may change his position, the subject stuck in the mirror stays still as pictorial representation. What's more, the observer has no access to the pictorial act, the work in fieri. In Gumpp, the observer, who stands behind the painter, is able to see what he does and how, but at the same time the view of the painter's face is hidden from him. What is hidden in Gumpp is revealed in Parmigianino. We may thus speak of works that are mutually complementary or even equivalent if we take their format into consideration. Both canvas are oval, but if Parmigianino allows for an extraordinary closeness, to the limit of the border-mirror (between the unreal of pictorial representation and the reality of the viewer), Gumpp allows himself to be observed at a distance and refers to the viewer a possible Pythagorean problem in the forms of the objects represented, encompassed and unified in the oval of the frame. So too might be considered oval the shape of a world, the painter's, in which the painter allows the viewer a peek, but always according to his own rules.

Through the non-realistic dimensions of his painting, Gumpp induces in the viewer a perception that what is seen is the reproduction of a reality (real or imagined). Parmigianino's painting, on the contrary, is a fantastic trompe l’oeil. The painter makes the limits of pictorial representation coincide with those of the mirror in which he represents himself: the frame is the mirror.

Gumpp is the pictorial text, Parmigianino its synthesis. In this synthesis the representation, which wants to achieve the status of an object of the real (mirror in space-reality), is identified with the real object (mirror as material object), thus becoming object in all its materiality.

The painting becomes an illusory machine, a painting(-mirror) that reflects the talent of the artist who, in his self-referentiality, claims to be his work's creator, his world's king.[3] The painting becomes an act of human vanity in trying to perpetuate the matter in a future of which the author will be absent. If the painting has this power so too does it have the power of paradox that, founded in technique, takes the receiver to verify the validity of the assertion and demonstrate the mechanism that made it possible.

1670-1675 Cornelis Norbertus Gijsbrechts

The paradox materializes in the work of Cornelis Norbertus Gijsbrechts, The Reverse of a Framed Painting, a pictorial representation of the back of a picture: the part of the frame-matter, usually hidden, gets to occupy the foreground, that of viewing and contemplation. Due to its perfect technique, the spectator is compelled to verify the representation, turning the object backwards to discover the reality.

Just like Parmigianino's specular image, Gijsbrechts' image occupies the entire possible space: the image is everything. The only element that differs from reality is a number, «36». Maybe it's part of a collection, maybe it's just a number in a series that would define it as some work. In the history of art, as Stoichita proposes, this work should be numbered with «0». In this case its form wouldn't mean an absence but, on the contrary, it would be a psychic form with its own graphic form. Not nothing, but meaning the nothing. The paradox then is that even the act of talking about «nothing» elevates it to the status of «something». The nihil that matters in Gijsbrechts is the nihil negativum in virtue of which, quoting Stoichita: «the nihil negativum of the image is the image of the absence of image.»[4]

Michelangelo Pistoletto

1967 Le ultime parole famose

«When my need to understand things came to include the consideration of life itself, I instinctively understood all of the conflicts in the system of doubling all things of the universe. Looking at works of art, I felt the force with which I was compelled to oscillate between one dimension of experience that was abstract and mental and another dimension of experience that was concrete and physical. And it was in the fact of representation that I discovered the poles that were in simultaneous attraction and repulsion - my literal presence as proposed by the mirror, and my intellectual presence as proposed by my painting. These two presences of myself were the two lives that were simultaneously tearing me in two and calling me with ur- gency to the task of their unification.»[5]

Michelangelo Pistoletto brings together in his experiment two hundred years of Flemish painting, from Jan van Eyck's, The Arnolfini Portrait (1434) to Gijsbrechts' The Reverse of a Framed Painting (1675). Pistoletto is Van Eyck, Vermeer, Velásquez, Parmigianino, Rembrandt and all the artists on whom Stoichita writes in his L’instauration du Tableau. Pistoletto is Stoichita as well. The theoretical starting point is distant and mythical: «Man has always attempted to double himself as a means of attaining self-knowledge. The recognition of one’s own image in a pool of water - like recognizing oneself in a mirror - was perhaps one of the first real hallucinations that man experienced.»[6]

Pistoletto is Parmigianino who, instead of extending the edges of the frame to match those of the mirror, carries «art to the edges of life in order to verify the entire system in which both of them function.»[7]

Pistoletto is Rembrandt who instead of stepping back three paces, places himself beside the canvas, escaping from its overwhelming power. «In my new work, every piece grows out of an immediate simulus of the intellect (...) Each successive work or action is the product of the contingent and isolated intellectual or perceptual stimulus that belongs to one moment only. After every action, I step to one side, and proceed in a direction different from the direction formulated by my object, since I refuse to accept it as an answer. Predetermined directions are contrary to man’s liberty.»[8]

Pistoletto is Velásquez in the specular game between walls-ends and homonymous characters, on the infinite possible speculations about his Meninas, in the workable perspectives and in self-referentially: «The beginning and the end of this story is the wall. For it is on the wall that pictures are hung; but mirrors are fixed there too. I believe that man’s first real figurative experience is the recognition of his own image in the mirror: the fiction wich comes closest to reality. But it is not long before the reflection begins to send back the same unknowns, the same questions, the same problems, as reality itself: unknowns and questions which man is driven to re-propose in the form of pictures. My first “question” on canvas was the reproduction of my own image: art was only barely accepted as a second reality. For some time my work went ahead intuitively in the attempt to bring closer together the two images – the one offered by the mirror and the one I myself proposed.»[9]

«The conclusion was the superimposition of the picture directly on the mirror image» as in Parmigianino, as soon as «the picture overlaps and adheres to the image of reality»[10] as in Gijsbrechts.

«The figurative object born of this action allows me to pursue my inquiry within the picture as within life, given that the two entities are figuratively connected.»[11]

Part of the difference between the self-portrait as a description of itself and the autobiography as life put in a story, is that the self-portrait doesn't tell anything but solely describes the state of the authoral self that can, ex post facto, become the story of the artist's personality. Pistoletto is then Stoichita talking about the corpus of Rembrandt's self-portraits considered, ultimately, an autobiographical story.

Pistoletto continues: «I do indeed find myself inside the picture, beyond the wall which is perforated (though not, of course, in a material sense) by the mirror. On the contrary, since I cannot enter it physically, if I am to inquire into the structure of art I must make the picture move outward into reality, creating the 'fiction' of being myself beyond the mirror.»[12]

These words evoke the date of 15 may 1871, when Rimbaud writes a letter to Paul Demeny declaring «je est un autre (...) J’assiste à l’éclosion de ma penseé: je regarde, je l’écoute...»[13] In the Italian context of 1960s Arte Povera and especially since the advent of Duchamps' urinal, «it is easy to play on the identity between reality-object and the art-object. A 'thing' is not art, the idea of that same 'thing' can be art.»[14] A valid concept, too, in the case of a painting representing its reverse. «The physical invasion of the picture in the real environment (bringing with it the representation of the mirror) gives me the chance to introduce myself among the broken-down elements of figuration.»[15] Continuing the theorization of his poiesis, between 1975 and 1976 Pistoletto reflects further about the Quadri Specchianti and the constant phenomenon that characterizes them: the relationship between the static image, fixed by the author, and the dynamic images of the mirroring process.

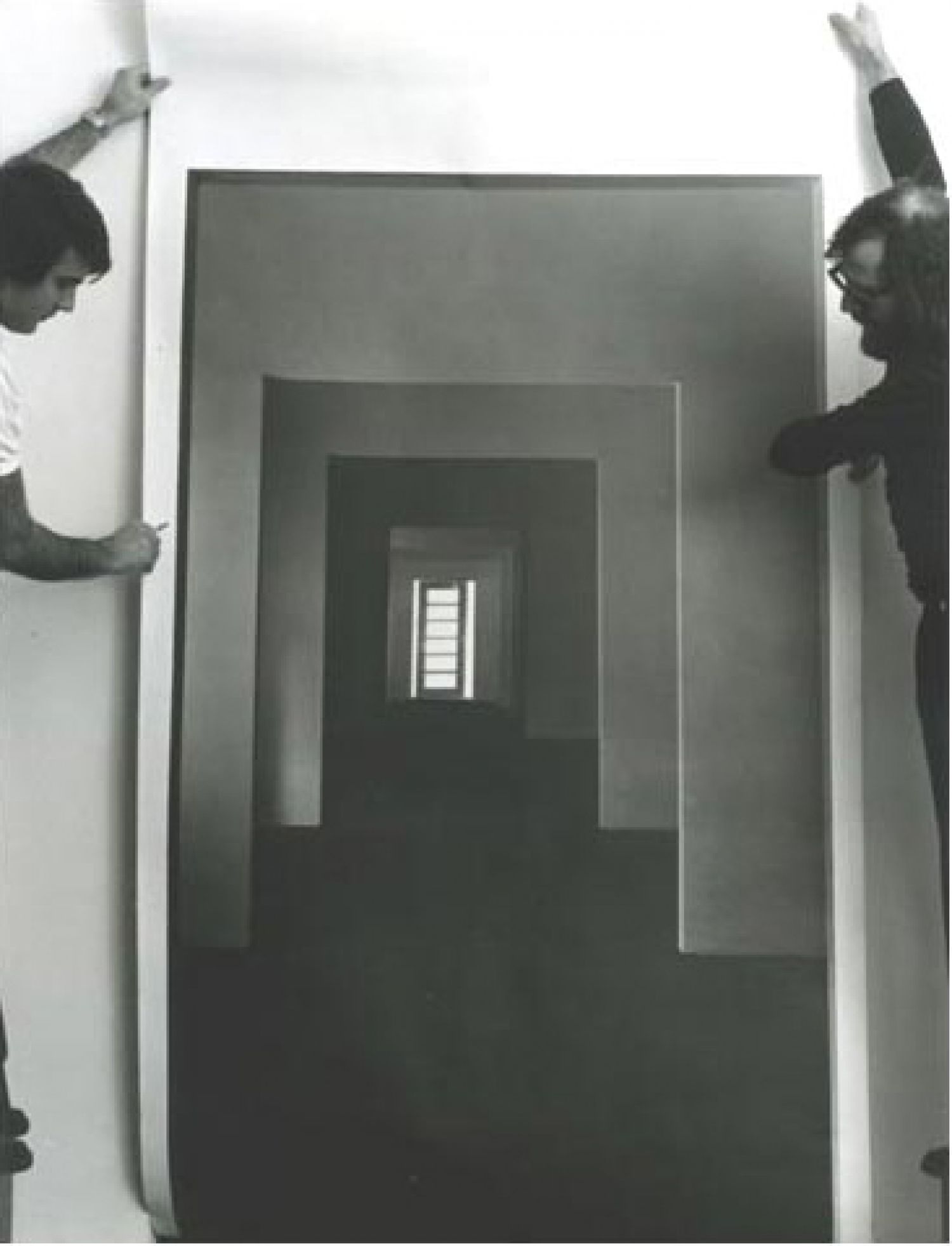

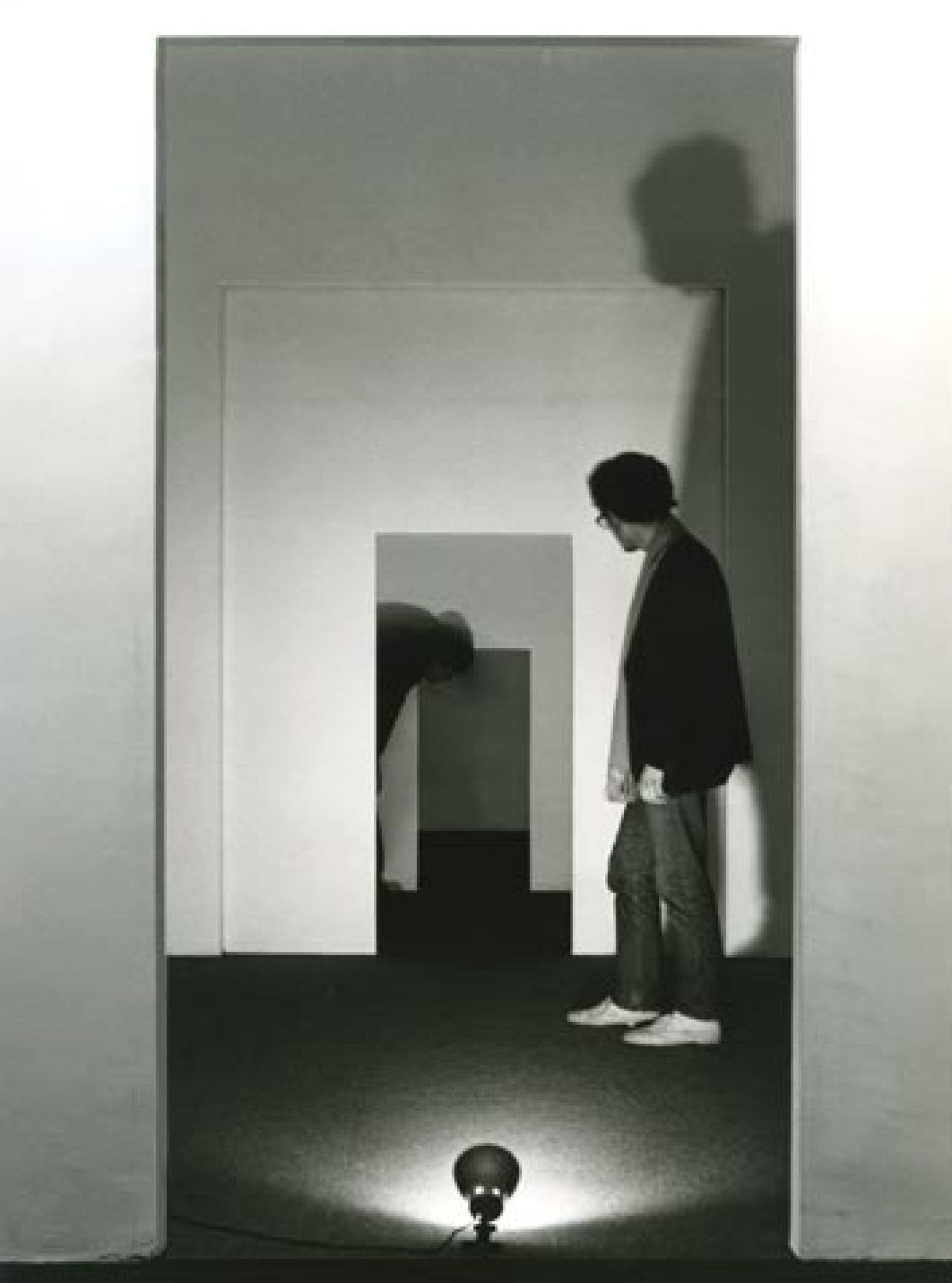

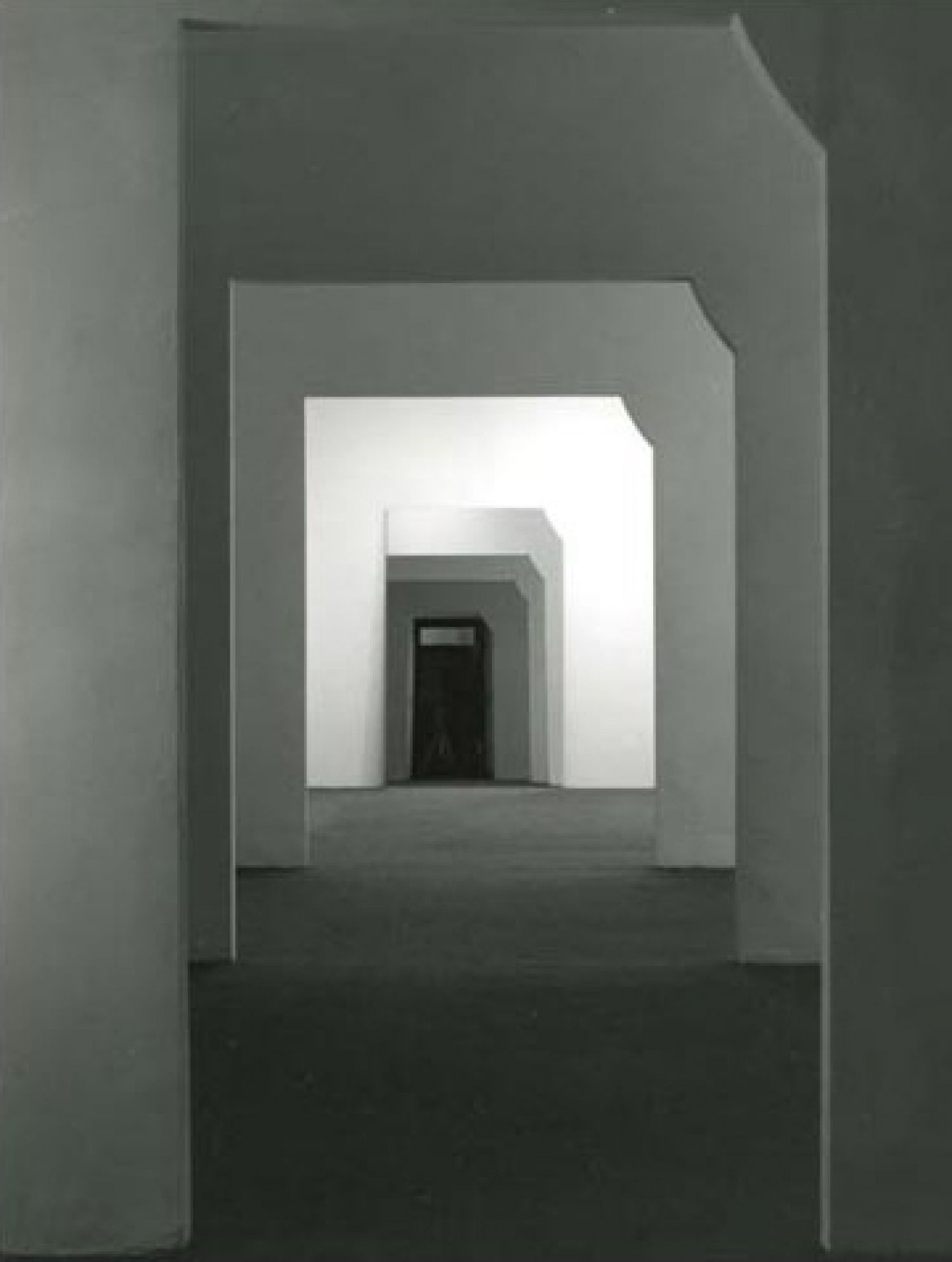

1975-1976 Le Stanze

The quadro specchiante works as a door to the rooms, Le Stanze[16], connecting the artist's installation and the visitor's route at the Galleria Stein in Turin. «The dimensions of the "doorways" are those of my mirror pictures (125x230 cm) and thus I imagined a mirror surface placed on the wall of the end room, as a virtual continuation of the series of openings from one room into the next. Until I saw this new gallery, I had never found a reason for exhibiting a mirror surface alone, without any form of intervention on my part. I found this opportunity here, if only by the particularity of the sequence of rooms and dorways. (...) There are many things I could say about this work; for example, that it cannot be transported elsewhere without relegating it again to the status of a mere mirror; that it ‘magnetizes’ all the space within the gallery by immobilizing it (by virtue of the fact that the gallery immobilizes the mirror for the duration of the exhibition). I could go on to speak of the viewer, and formulate a hypothesis about the immobility by which he would find himself surrounded (even if he were to move) should he realize that his relationship with the phenomenon is only one of ‘registration’. For his point of view in relation to the picture is immaterial, in that each and every point of the three rooms has been considered in perspective.»[17]

Pistoletto is both Velásquez, in creating a scenario that allows endless possibilities of reading, and Stoichita, speculating on these possibilities.

The mirror-representation earns material status and enters reality as an object able to reflect it, making it a work of art. That's why his pictures cannot be reproduced. «They cannot be transformed into other media, for that would mean the elimination of the dynamics which is their essential aspect.»[18] The reflection factor of mirror surface as an object increases exponentially the views that might be considered. «(...) About Le Stanze I'd say that the only proper medium for its documentation is the living eye which records it.»[19]

The performance changes of subject. If with the Flemish (and not only) it's the author who, depicting himself in the act of creation, records his action on the canvas in an attempt of temporal crystallization, in the Piedmontese artist's installation the visitor is both protagonist and witness. What is given is just the material for an experiment of which the artist is no longer part.

«The visitor's experience consists in walking up to the mirror (in the furthest and dimmest of “The Rooms”) to find that in it he is almost flat up against the light from the door he has just entered by: it seems that if he were to take another step forward, he would become one with the mirror surface, with no body and no reflection.»[20]

This apparent attempt to turn back to bidimensionality stems from an in-depth study of perspective, from Piero della Francesca and the Renaissance artists to the elaboration, by the Flemish, of an exceptionally refined technique of trompe l’oeil. In the second part of the exhibition path there's a photographic reproduction of the same exhibition, now revealed in actual dimensions and placed at the same doorway, which is a technical representation of the space previously visited. «The viewer will realize that the mirror has thus been 'trapped' by the camera, which has forced it to reproduce The Rooms in definite form.»[21]

The camera as a canvas, the finger on the camera button as the hand with the brush. Two eras far apart, a common will to crystallize reality in an eternal instant. Vanity is still present, no matter the different media: the artist may, thus, boundlessly contemplate his own creation.

Pistoletto's reasoning always adds an extra ingredient: a third moment occurs when he reflects on the use of media in reproduction, stating that «(…) In any piece of research, each single datum is precious. One should not therefore ignore the fact that a medium ‘overturned’ to serve creative expression not only becomes useful, but also declares its limits, fragility and precariousness.»[22]

These words echo the message of the works by Gijsbrechts, who, before reversing the canvas, shows the fragility of the artistic materials in his vanitas. Three stages from a path à rebours:

– The 1669 vanitas, a trompe l’oeil representation of a still life in a niche, which takes up and amplifies the tradition of the old Flemish painters;

– The 1668 vanitas, more complex in its message. The trompe l’oeil, defined by the coincidence between the limits of the niche and those of the frame, is cut by the unpasted upper right corner detached from the frame: it is the representation of the representation;

– The Boston vanitas, which represents part of a room, shown as a small part of a much larger space, no longer a mere object hanging on the wall of the artist's workshop.

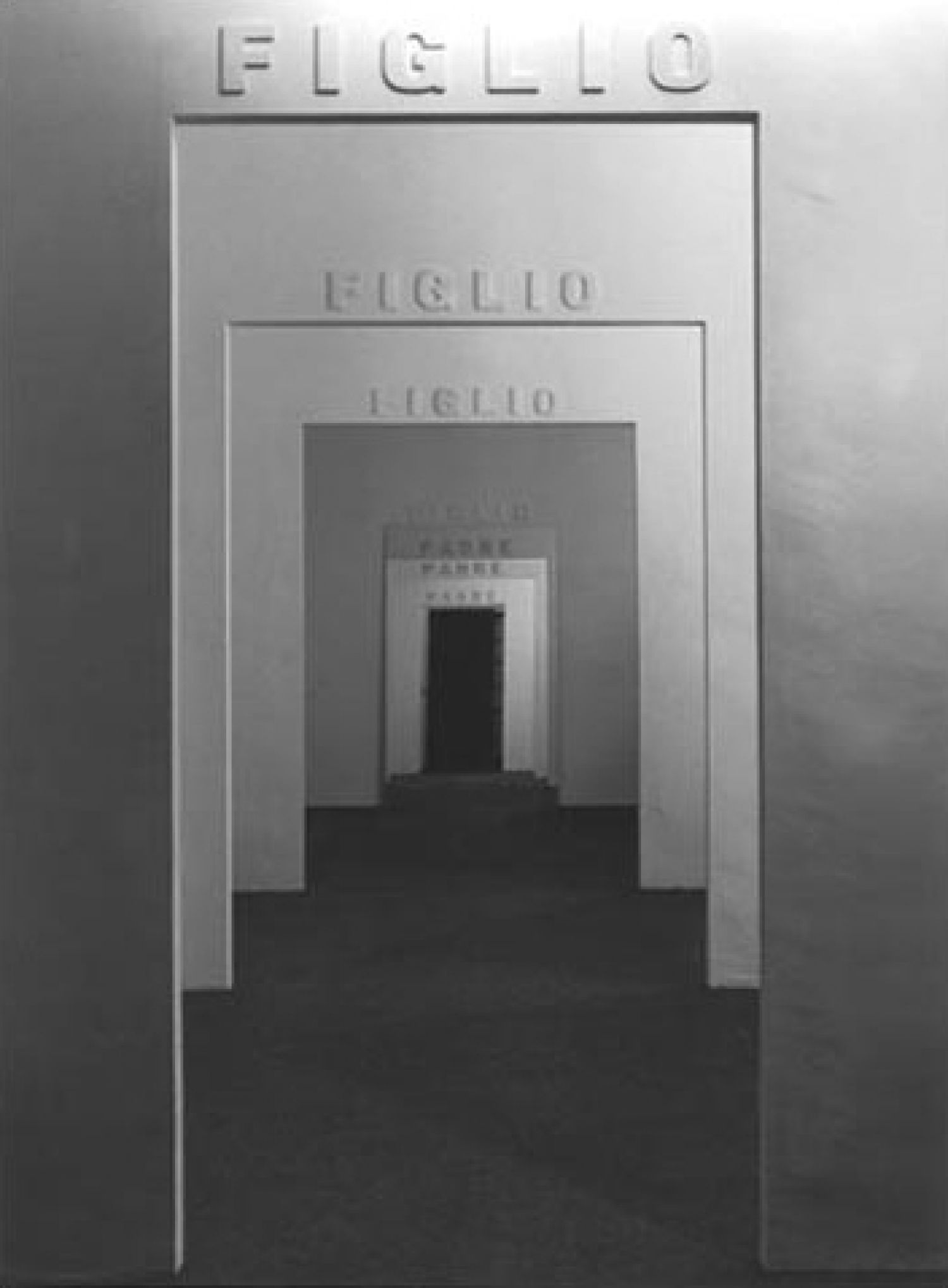

In the third exhibition of The Rooms series, the author explains the meditative intention. «The word ‘figlio’ (son) is repeated above each doorway up to the threshold leading beyond the last of ‘The Rooms’. But this time, the illusion that the mirror reflection simply continues the series of openings and rooms is dispelled, since in the reflection it is the word ‘padre’ (father) which is repeated from doorway to doorway, from room to room. The reflection never gives back its own side, but the opposite. Thus, in virtue of this seventh opening or threshold, which I call the creative point, we are enabled to see ourselves come and go. But I would add (...) that we cannot consider ourselves as entirely ‘fathers’, until we have walked the entire length of the path of the sons.»[23]

The artist is aware of the importance of his predecessors' experiments, but inevitably surpasses them. He is not only the son of the process of evolution in the history of art, but also of the society in which he was born and where he operates. He is the son of a different historical moment, in which the evolution of the technical means of reproduction of the work of art offers multiple solutions. He is the son of a world where the notion of subconscious widens the spectrum of speculations about the true nature of the human being as such, whereas the theory of relativity refers all under discussion.

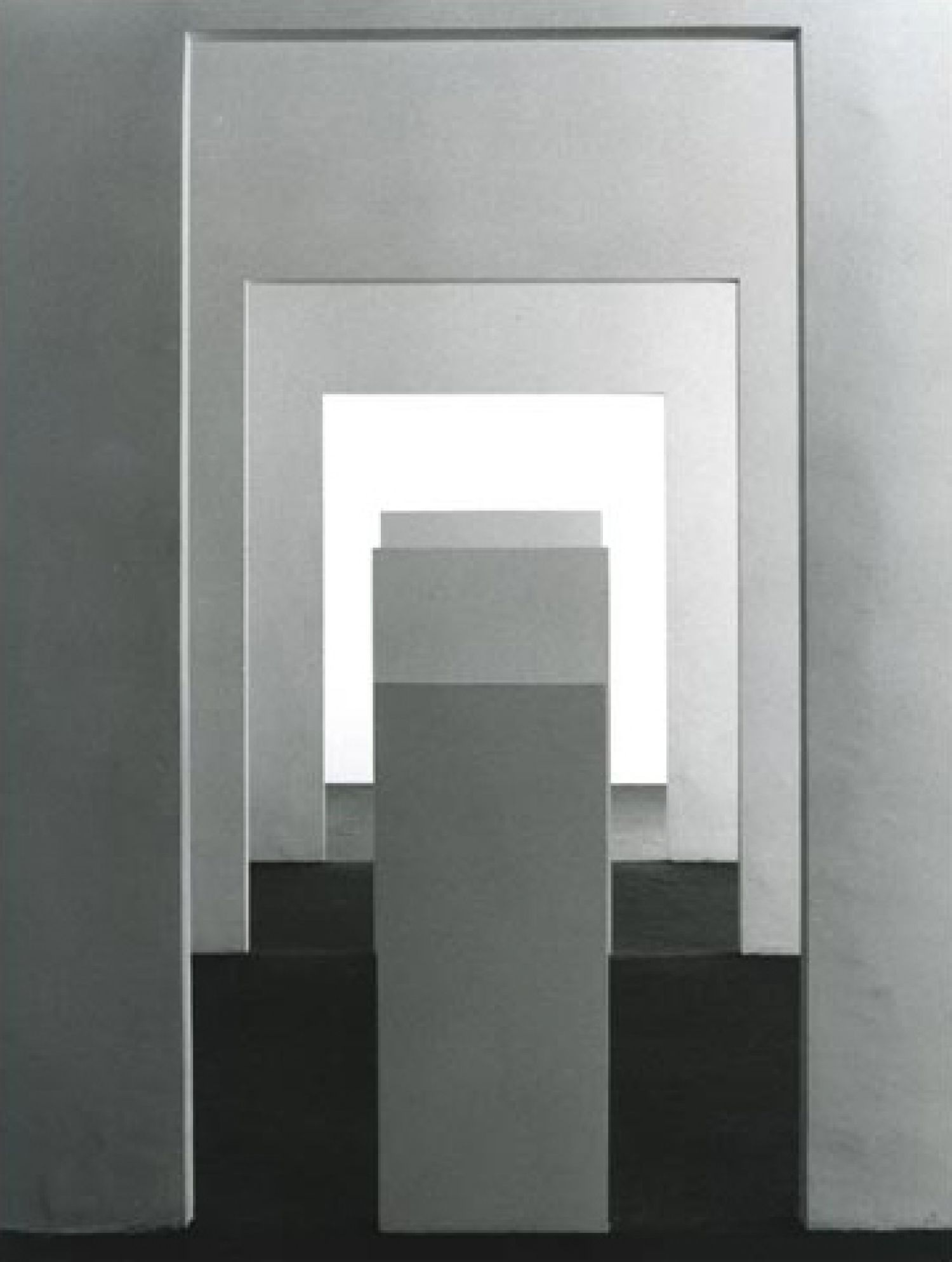

In the fourth act of The Rooms the father is surpassed by the son both on a practical and theoretical level. «The particular point on which I should like to focus attention is the fact that there are three “doorways” which become seven through reflection». The artist continues: «Only recently scientists discovered the law that all phenomena can be verified in mirror form, except one.»[24] The limits of the human being are always recognized: «Whenever we arrive at a discovery via the instruments of art, it is never microscopic or macroscopic, but always in a human dimension.»[25]

The reasoning is inspired by the pythagoreans and by the field of quantum physics:

«Number three encapsulates the parity of the two (the father and the son) who are reflected in the uneven, central point (the mirror). Four is even and does not reveal disparity in any way. In number four the central point in which the opposing points find verification generates a cross, since it is transfixed not by a single line of projection (as in the previous show) but by two, which form four equal angles. The four points are now, as it were, at the extremities of two intersecting mirrors. Each point is projected sideways onto the mirror surface, instead of striking it directly. (...) this symmetry of parity would prevent us from verifying our double optically, shifting our gaze toward the two lateral points which represent the width of the mirror before us, while our reflected image would take shape at the opposite end of another mirror. We see this mirror sideways, as on a knife's edge: indeed it has our own thickness, exactly as it has the thickness of a point.»[26]

Imagination enters another dimension: «Optically, therefore, we would be able to perceive only two dimensions. But after the experience of the third, we can imagine the fourth.»[27] where space-time undergoes expansion and acceleration: «At minimum speed we have maximum space; and with maximum speed we reach the four points which stick firmly to the central one (still hiding it). For this reason show number four cannot but be ‘Time’ - the time we take (or which the instrument takes) to move from one point to another point within The Rooms.»[28] In the pistolettian rooms one travels another reality which foresees its own physical laws; one travels in the time of art history that speeds up to a future imagined in another dimension, but also in personal, intimate universe that one keeps inside, in the subconscient, which the artist encourages to explore through reasoning.

«In the exhibition, the terms of time itself are pushed to extremes, beyond the imaginationless dynamic which lines the environment. But here imagination presents itself at the same time as its explanation. I have loaded the future with memory; and this memory seeps away automatically with every moment that enters the past; while the instruments which mark the passage of time mechanically do not move beyond their mechanism.»[29]

The text is considered in its rhetoric function of ekphrasis and its documental role before and after the completion of the material work: «(...) Thus my inquiry delves also into the mechanisms which make thought proceed. Indeed, each of these writings on the exhibitions precedes the actual concrete realization of the exhibition to which it refers and follows the moment in which the exhibition has been conceived. Each separate piece of writing becomes a functional part of the work itself, since its words adjust the trajectory of the imagination while each of the exhibitions adjusts the trajectory of the writing.»[30]

The artistic media work together to create, implement and conceptualize the installation. But each medium has a defined role: «the written work is simply a part of the engine, which cannot be replaced by another mechanism.»[31] This is the reason why Michelangelo Pistoletto doesn't write much more about the fourth experience of The Rooms. The writing must not be the materialization of each individual's imagination.

This uniqueness, along with centrality, has the main part in the fifth exhibition. In this one «the dimensions vary along with the expansion or contraction of volumes around that center on which all diagonals converge. Thus, just as a cube may be any size you like but will always have the same center, so 'The Rooms' now contract and expand physically around their central point.»[32] As with this reduction-expansion, the sixth exhibition theorizes the dilation of the father's expression in his own son. The poetic image created by the words gain life in the Galleria Stein, now a microcosm that mirrors the macrocosm of life and family relations. «(...) the real title of this sixth exhibition ought to be Moving Away. (...) The farewell is the symbol of this parting.

The father, as he moves away, sees the image of his children diminish then disappear entirely. Of course, the children do not get smaller in any real sense, nor do they disappear: they remain the same as always, but elsewhere.»[33]

The real and the virtual are thus like phenomena to split in order to double the rooms, as if they penetrated the mechanism of optical perspective. «Reproduction waives its claim to total substitution of the gallery, and real space absorbs reproduction.»[34], like the 17th century wall of an artist's workshop absorbs a remarkable trompe l’oeil executed by Gijsbrechts. The wall always shows the boundary between representational fiction and the reality of matter.

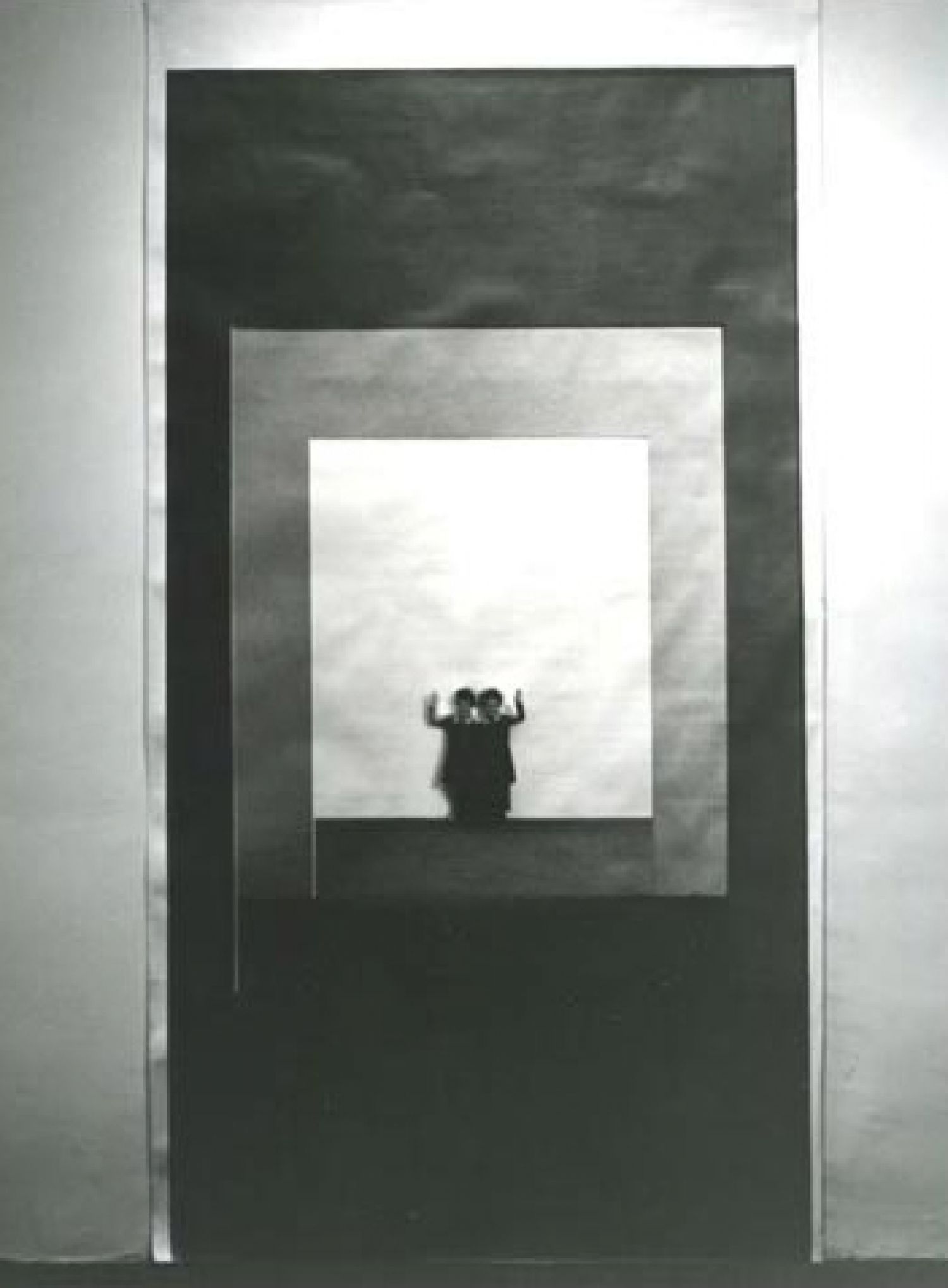

In the seventh exhibition (a specular reproduction of the first exhibition), which pushes the concept much further, a performer breaks a rectangle of the mirror placed at the rooms' end, later applying «plaster to the inside of the doorways so as to give the openings the same new shape as the mirror. Thus these openings will be ‘false’ - both on this side and the other side of the mirror - whereas the mirror itself will be its real shape.»[35]

It gets more complicated in the eighth, in which «positive and negative, fullness and emptiness, are intertwined without allowing us to make out the point of interchange between reality and image», which the author identifies with the mirror. «Thus, mingling the imagined vision with the physical one, the eye may set out either from the entrance or from the far wall beyond the three doors.»[36] The image presented is justified as «corresponding to the dimensions of the first door, but seen in perspective, standing at the other end of the Rooms.»[37]

In the ninth exhibition the positive is the world of the living and the negative is the world of the dead. «My ninth exhibition is the visit to hell. But its title is Approach (...) the stone which seals off the world in which my mother now lives will be placed against the far wall of the gallery. This stone will appear as a virtual threshold, separating two forms of a single reality.»[38]

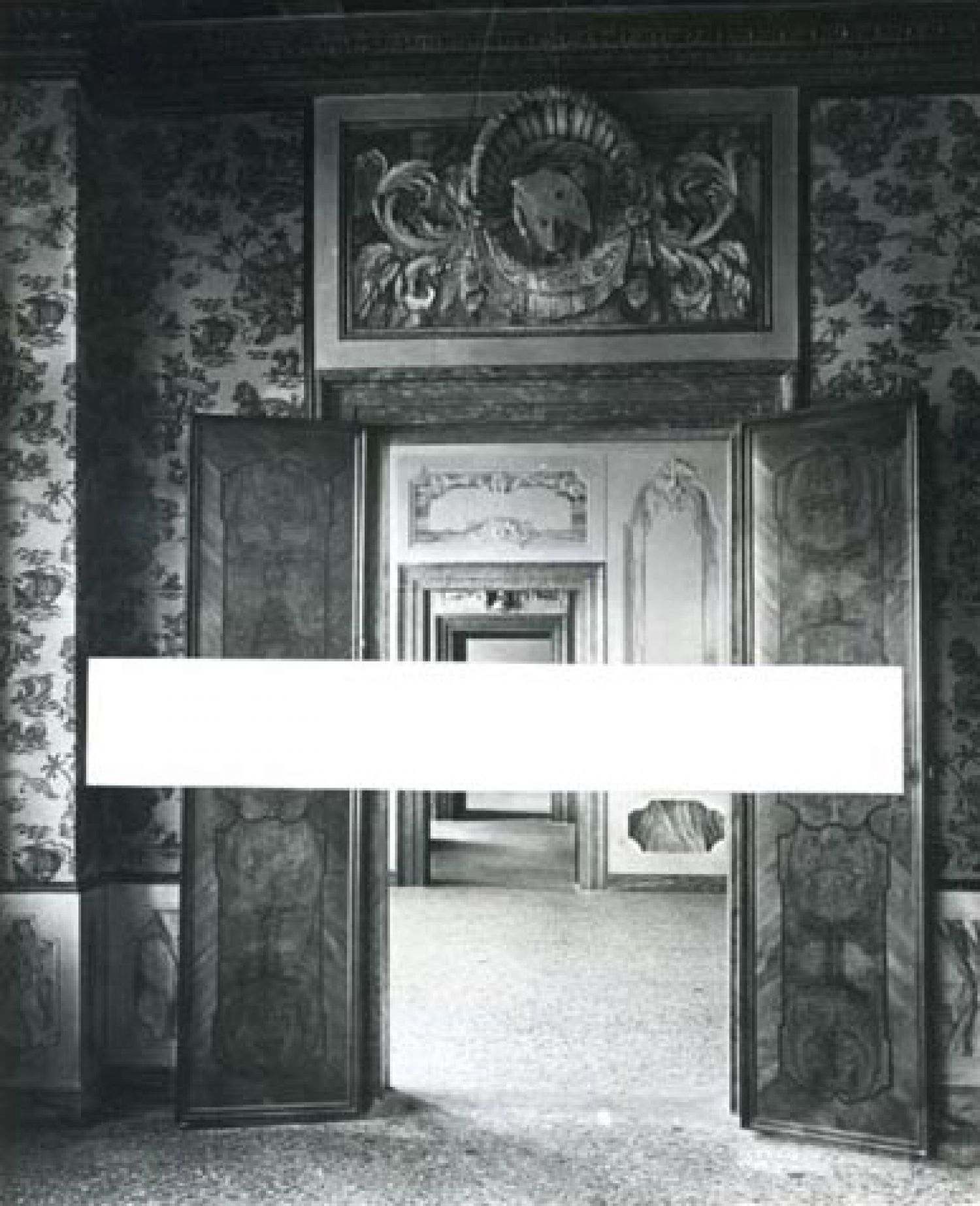

All the real and imaginary realities known by the artist are explored: part of the real reality of the Gallery rooms exposed in their nakedness and naturalness in the tenth exhibition; and we pass a dreamlike reality in which the walls of Baroque Venice suggest a perfection of style and the saturation of the available space. «(...) I had occasion to visit a number of Venetian houses, with baroque rooms in which I found the same perfection of image. Here, too, no part of any wall was without its stylistically perfect detail. These real rooms are the physical exposition of the single dream of the person who imagined them. (...)The title of this eleventh chapter is The Transfer.»[39] At the moment of literary production, Pistoletto gains conscience of the «alchemic» process through which the ink becomes word in the paper sheet's white rectangle, just like the white rectangular wall of the Galleria Stein is the ideal support to the reality of written words.

In the last chapter, the wallpaper's white is opposed by the black of an unwritten sheet of paper, sent by the gallery «to the recipients of the preceding eleven blurbs (...) as the announcement and execution of the twelfth exhibition.»[40]

The monochrome paper sheet fits the artistic milieu contemporary to Pistoletto. During the Sixties one takes as a starting point «the factual feature of the configured matter»[41] to achieve an expressive efficacity impossible on personal and emotional traits. The spectator becomes extremely important because it's up to him to complete the work, he is called to actively participate, through a continuous interaction with the work of art that in this particular case is the black paper.

The collaboration between spectator and work of art is not in itself new. This has always been required by the artist. Even Gijsbrechts' trompe l’oeil wouldn't make sense without the viewer's reaction. But in Pistoletto new conditions arise, different from those that existed in the Flemish past. It's accepted that the artwork is only partly the ultimate creation of the artist, for it must be completed in the process of fruition.

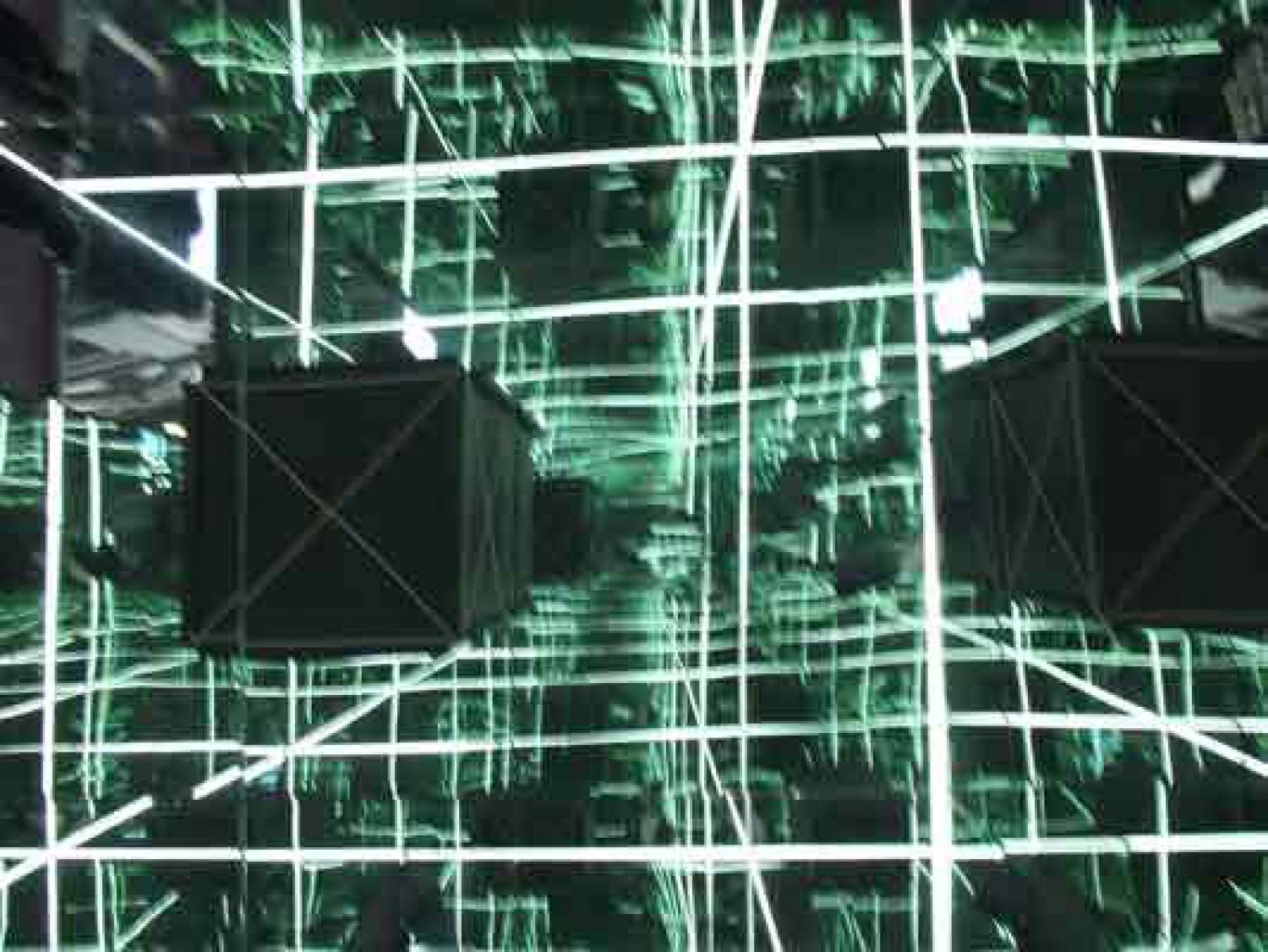

2009 Venice Biennale

Michelangelo Pistoletto breaks 20 of 22 mirrors aligned in one of the rooms of the Arsenal of Venice.

«The broken mirror leaves black forms, the document of an act, a snapshot of a past memory. The mirror which represents the 'here and now' refers to a creative act that has already 'passed'. That black was a 'present'. The paradox is in the mirror becoming witness to what has been and what will be. (…) it's the nothing that contains the everything, and also what should be.»[42]

It's Gijsbrechts' paradox and the number «0». The same «black» of the monochrome letter sent on the twelfth exhibition of The Rooms.

Reading the black parts in the perspective of quantum physics, these can be imagined as black holes that «may be apertures to elsewhen. Were we to plunge down a black hole, we would re-emerge, it is conjectured, in a different part of the universe and in another epoch in time.»[43]

Pistoletto himself writes, on account of his 2000 installation[44], that «the mirror works as a bridge between visible and invisible. (…) It potentially reflects any place and keeps reflecting even in the absence of the human eye.»[45]

Reflection, far from a pure physic phenomenon, becomes interior and private. If art is depository of a nearly infinite possibility of reflection, reproduction and recreation of universal reality, then isn't the mirror the most adequate means for man's contemplating activity?

The reflected image of the man is the man but in another space, that of the mirror. If the present is in practice the only moment in which we live, it is then our world. Therefore, the reflected image lives in another world, a parallel world.

If black holes may be entrances to a Wonderland, could the pistolettian mirrors be considered portals for the knowledge of the being? Could reflected image be an alter ego?

2010 Palazzo Strozzi, Florence

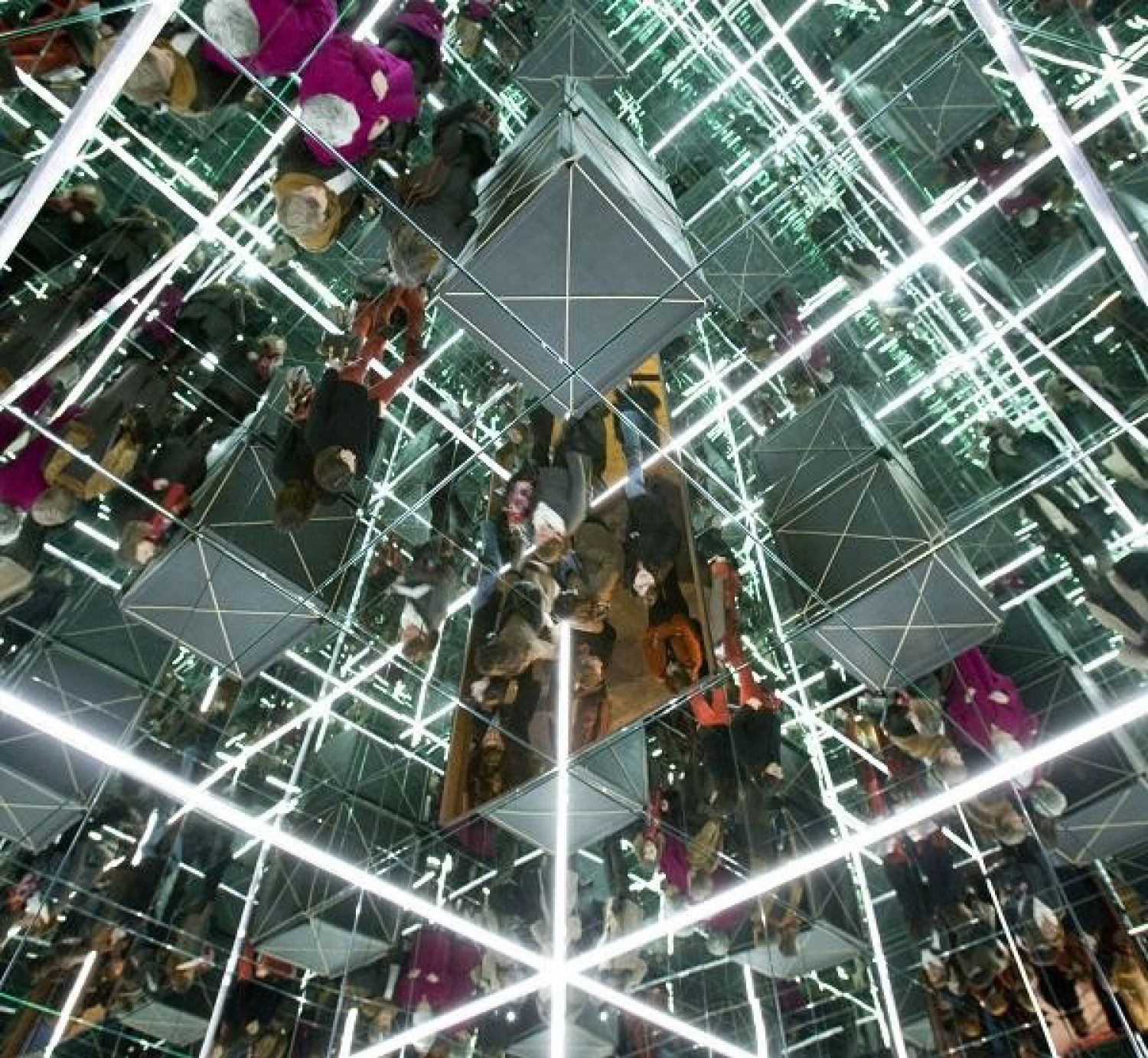

Metrocubo d'infinito in un cubo specchiante (Cubic Meter of Infinity in a Mirror Cube) is the name of one of the most recent installations that Pistoletto placed in the Renaissance courtyard of the Palazzo Strozzi, in Florence. It is a cubic structure covered by opaque steel plates and internally coated with mirrors. At its center, another cube: Cubic Meter of Infinity, a work carried out in 1966, also made up of reflective surfaces.

«Beyond the technical title, the idea is that the individual who steps into my mirrored cube will live an experience of the universal kind. He who is reflected, sees his image reflected to infinity. (…) It's going far in a real way, not divine or metaphysical, in order to return to the present. And there is another cube that, in turn, reflects itself»[46] taking the reflection possibilities to the limit.

«Inside, the visitor finds another cube that also is repeated to infinity, but where he can't enter, because it's intangible. A mystery looms, soon resolved, for inside the large cube one can live the experience of the intangible cube's interior. In other words, the experience of knowing, of imagining.»[47]

The installation's Renaissance frame helps in the reflection on a glorious past which must be rediscovered for its importance in our understanding of who we are and the direction we're going. The multiplication and division already explored in 1978 reappear differently but with the same intention of unifying the one and the all. Man as a multi-faceted being but also an element-individual part of the whole-society, or whole-world, whole-universe. Man who should know his past in order to reflect on his present and improve his future.

On a structural level, Cubic Meter of Infinity in a Mirror Cube is a hypercube. A hypercube is the theoretical proposition of a fourth dimension polyhedron. To understand the geometric representation of a hypercube, we must resort to an analogy: to form a square, we unite two parallel line segments of equal length through its ends by two other line segments. To represent a cube, we join the vertices of two squares by four line segments. To represent a hypercube, we unite all vertices of two cubes by line segments. This cube's dimensions are greater than the three commonly known and perceived: length (or depth), width and height. The fourth dimension (spatial) is orthogonal to other spatial dimensions and should be identified with time (or the time dimension). But considering that time coincides with the fourth dimension comes from research on the studies of functions in mathematical physics. In 1754 it was formulated for the first time the possibility of time being a fourth dimension. The acceptance came in 1895 with The Time Machine by H. G. Wells. The time traveller presents his knowledge to the audience: «You must follow me carefully. I shall have to controvert one or two ideas that are almost universally accepted. The geometry, for instance, they taught you at school is founded on a misconception. (...) I do not mean to ask you to accept anything without reasonable ground for it. You will soon admit as much as I need from you. You know of course that a mathematical line, a line of thickness NIL, has no real existence. They taught you that? Neither has a mathematical plane. These things are mere abstractions. (...) Nor, having only length, breadth, and thickness, can a cube have a real existence. (...) Can a cube that does not last for any time at all, have a real existence? (...) Clearly, the Time Traveller proceeded, any real body must have extension in FOUR directions: it must have Length, Breadth, Thickness, and—Duration. But through a natural infirmity of the flesh, which I will explain to you in a moment, we incline to overlook this fact. There are really four dimensions, three which we call the three planes of Space, and a fourth, Time. There is, however, a tendency to draw an unreal distinction between the former three dimensions and the latter, because it happens that our consciousness moves intermittently in one direction along the latter from the beginning to the end of our lives.»[48]

However, Wells acknowledged that the allure of the speech wasn't simply in the concept of time, but also in space, the fourth dimension where one lives without perceiving it. A work like Pistoletto's leads the observer to think about who he is and about his position in the world or even in several worlds. It's a cube defined by walls of steel which opens inside the possibility - if we accept that life in the mirror can be real - to explore thousands of possible worlds. It's a universe in a room which resembles the Misner space, but looking for a past memory capable of embracing the present in order to create a better future. In the Misner space, where such space is idealized, the cube can contain an entire universe. All the opposite walls identify with each other, so that, crossing a wall, one immediately emerges from the opposite wall. The ceiling too, identifies with the floor. thus, if we passed through the walls of the cube we'd be back to the same room. The walls being mirrored, each of them is a boundary between the cube's internal room and other identical rooms infinitely reproduced. In fact, there is an exact clone of the viewer in each room, who will act in an equal manner and oppose the viewer's every action. The Misner space is often studied, because it has the same typology of a wormhole.[49] If the walls moved, then time travel would perhaps be possible in the universe of Misner. If time travel is not physically possible to the spectator of art, on the other hand he's able to do a self-introspection journey, from the universal macro to the personal micro. Self-analysis admits the difficulty of the observer in observing himself. The mirror is a means because it 'duplicates' the individual, in an attempt to overcome the duality referred, in a comtian evocation, by Pistoletto.[50]In the hope of a utopian world reminiscent of Giordano Bruno, the master of the Italian Arte Povera leaves a message: «The past has good and positive parts, and a negative part that is a warning. It leads ahead, but the current progress reveals the downside of that past. This is why I think the revisitation of the past has in itself the seeds of the future: it allows us to free ourselves, if we build well, from what is negative.»[51]

Conclusions

Michelangelo Pistoletto proposes a concept almost definable as «art communism». The art that today is no longer elitist but accessible to everyone, because we all form the society, we are a single one divided into thousands of individuals. To awaken their conscience through specular and introspective reflection is a means to achieve the construction of a New World based on a new Humanism of Renaissance flavor. Time travel through the ages is thus inevitable in the formation of a social, historical and artistic conscience. But the individual too cannot be part of a whole without the perception of what he himself truly is. Therefore, travelling in the past is also travelling in various times of a person's life, attempting a self-exploration through the mirror's reflection. The mirror links the conscious self to the subconscious self and tries, through the image, to unify them for a life in harmony: with themselves, with the other, with the whole. Art becomes crucial, for «while life may imitate art, it is nevertheless also true that art imitates life.»[52]

Footnotes

- ^ PISTOLETTO, Michelangelo. Le Stanze, October 1975-September 1976. Text written by Pistoletto as theoretical support to the exhibition's concept. Available in the set of texts published on the author's official website.

- ^ Michelangelo Pistoletto's interview by Corona Perer, Crescete e dividete, at the 53rd Venice Biennale, 2009. In Sentire 07. Mori: LA GRAFICA srl, July 2009.

- ^ «If art is the mirror of life, I'm the glazier» – Michelangelo Pistoletto. Divisione e moltiplicazione dello specchio – L’arte assume la religione (exhibition catalogue). Turin: Galeria Giorgio Persano, 1978.

- ^ STOICHITA, Victor. (1999). L’instauration du Tableau, 2nd ed. Geneva: Librarie DROZ S.A., p. 366.

- ^ PISTOLETTO, Michelangelo. (1967). Le ultime parole famose. Self-published.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ PISTOLETTO, Michelangelo (1964). I plexiglass. Turin: Galleria Sperone.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ In 1999 Pistoletto publishes Shifting Perspective (‘I Am the Other’), a book for the Museum of Modern Art (Oxford, England).

- ^ PISTOLETTO, Michelangelo (1964). I plexiglass. Turin: Galleria Sperone.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ A project of twelve monthly exhibitions, from October 1975 to September 1976.

- ^ PISTOLETTO, Michelangelo. (1975-1976). Le Stanze, in La cittá di Riga magazine. Pollenza (Mc): ed. La Nuova Foglio.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ A seeming reference to the notion of chirality.

- ^ PISTOLETTO, Michelangelo. (1975-1976). Le Stanze, in La cittá di Riga magazine. Pollenza (Mc): ed. La Nuova Foglio.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ The fourth dimension is a dimension orthogonal to the other three spatial dimensions, that is, length (or depth), width and height. If one considers the time as a fourth dimension then it would be possible to speak of multidimensional spaces with more than four dimensions.

- ^ PISTOLETTO, Michelangelo. (1975-1976). Le Stanze, in La cittá di Riga magazine. Pollenza (Mc): ed. La Nuova Foglio.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ BARILLI, Renato. (2005). L’arte contemporanea. Milan: ed. Feltrinelli.

- ^ Michelangelo Pistoletto's interview by Corona Perer, Crescete e dividete, at the 53rd Venice Biennale, 2009. In Sentire 07. Mori: LA GRAFICA srl, July 2009.

- ^ Carl Sagan in KAKU, Michio. (2004). Parallel Worlds. New York, Doubleday.

- ^ Michelangelo Pistoletto, in BERTOLA, C. (1998). Pistoletto. Milan.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Michelangelo Pistoletto's interview by Mara Amorevoli, Nel cubo di Pistoletto Esperienza d’infinito, in “La Repubblica”, Rome, 27 August 2010.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ KRAUSS, Lawrence M. (2007). Dietro lo specchio. Turin: ed. Codice.

- ^ A wormhole means a structure linking two black holes in separate universes, as well as in separate regions of the same universe. As defined in theory, a wormhole creates a bridge between two black holes and, consequently, between two different regions of spacetime.

- ^ According to Comte the thinking subject cannot be split into two, one who thinks and another that analyzes himself thinking: 'Nobody can stand by the window to view himself pass in the street'.

- ^ Michelangelo Pistoletto's interview by Corona Perer, Crescete e dividete, at the 53rd Venice Biennale, 2009. In Sentire 07. Mori: LA GRAFICA srl, July 2009.

- ^ KRAUSS, Lawrence M. (2007). Dietro lo specchio. Turim: ed. Codice, p. 75.