Masks are the true faces

Jorge Alderete + Katherine Sirois

The collective dimension in works of art can operate on a more abstract level than the direct collective actions groups can undertake. Just as the notion of intertextuality in literature refers to the complex interrelationship between several texts in the shaping and meaning of a new literary work, the notion of intermediality can be used in the visual art field to define the interconnection between several visual works of art in the art making process. Because art is by definition made of interdependencies, each work of art is «a mosaic of references and quotations that have lost their origins » (Kristeva’s definition of intertextuality). In certain cases, the references and quotations are not lost, but are made of a visual compound of the art work, something being explicitly absorbed, exposed and named. The collective dimension is an active constituent of any artistic and semiotic community. It’s alive.

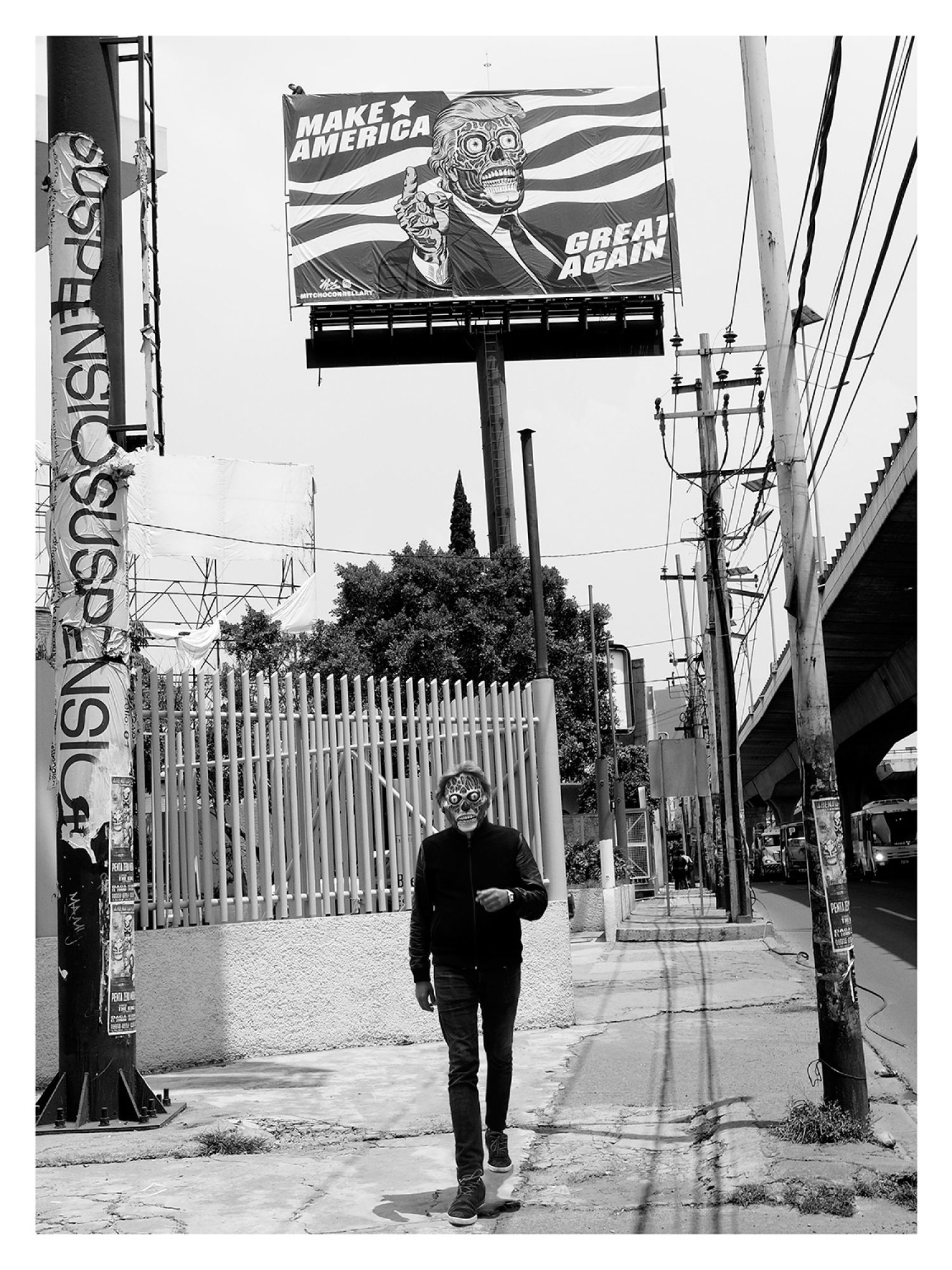

In 1988, John Carpenter released the iconic «B» movie They Live, a philosophical «science fiction» piece, which he rather referred to as a «documentary». The film was based on the issues of reality and perception, truth and illusion and on the sprawling ramifications of the power strategies to maintain status quo. Behind the grotesque of an alien invasion – some kind of humorous metaphor for inhumane and corrupted creatures – it aimed to talk about mass social engineering, manipulation and mind control, about conformism, deep alienation and alteration of the independent and critical thinking capacity by the systematic use of several hypnosis techniques like advertising, TV shows and mainstream media set up all around, in everybody’s life and environment. It aimed to talk about power and servitude, about hypocrisy and duplicity, about the contrast between the apparent aseptic scenery and the unfathomable psychological aberrations that are hidden in the American society. Alfred Hitchcock, John Frankenheimer, Stanley Kubrick and David Lynch have been some of the great masters in this theme reflection. They Live also aimed to talk about the extraordinary contrast between the happy few who possess the knowledge of what is really going on behind the scenes, and the rest, living in a total state of blindness, disregard and ignorance, despite their illusory believe in self empowerment and autonomy through basic material consumption. A decade before the Matrix, Carpenter was tapping right into the social consciousness shaped by politics and marketing, corporations and slogans intending to reduce the human diversity and potentiality to a mindless and minimalistic behaviour system that goes around in circles from obedience and consumption to reproduction and conformism.

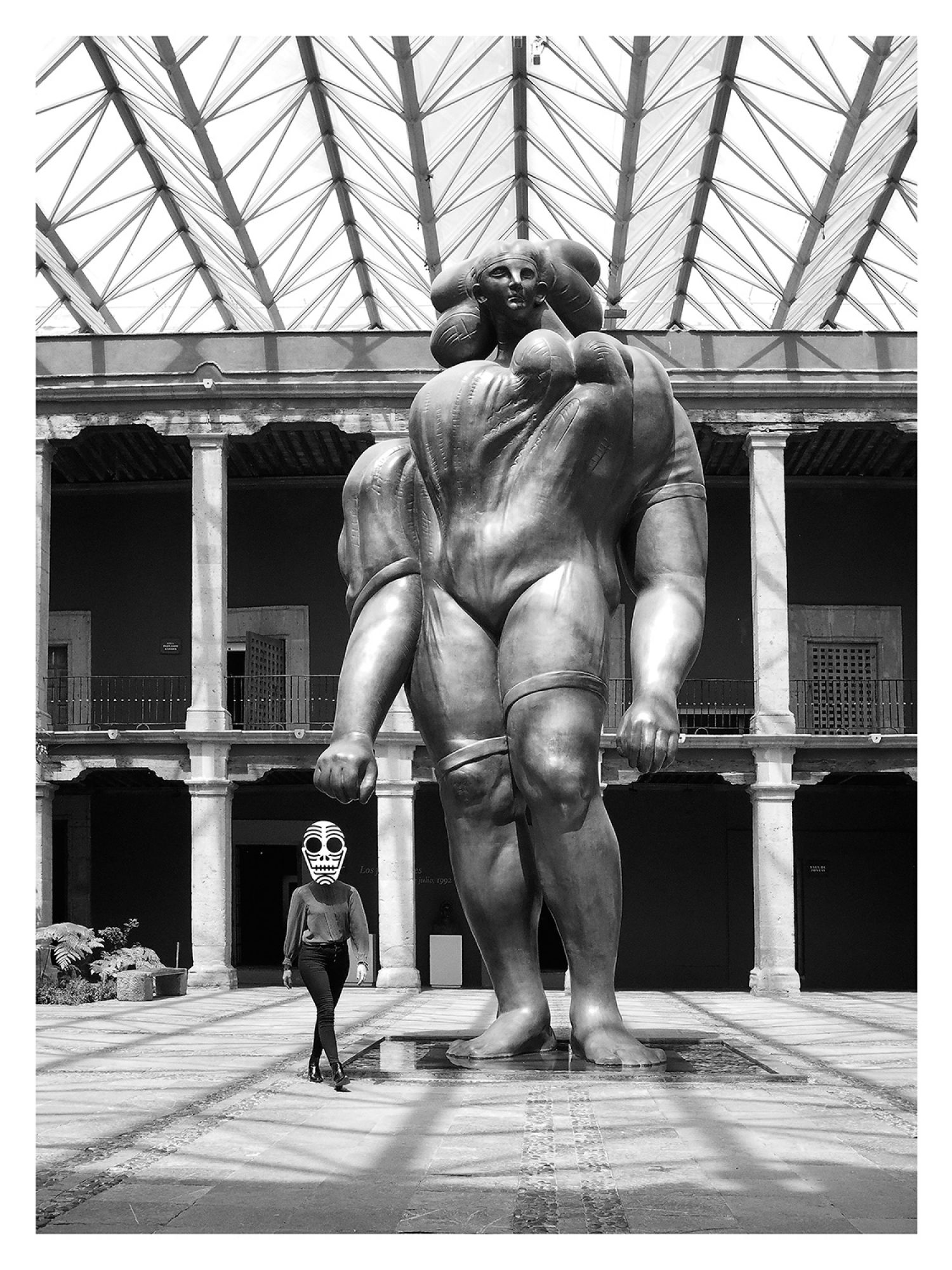

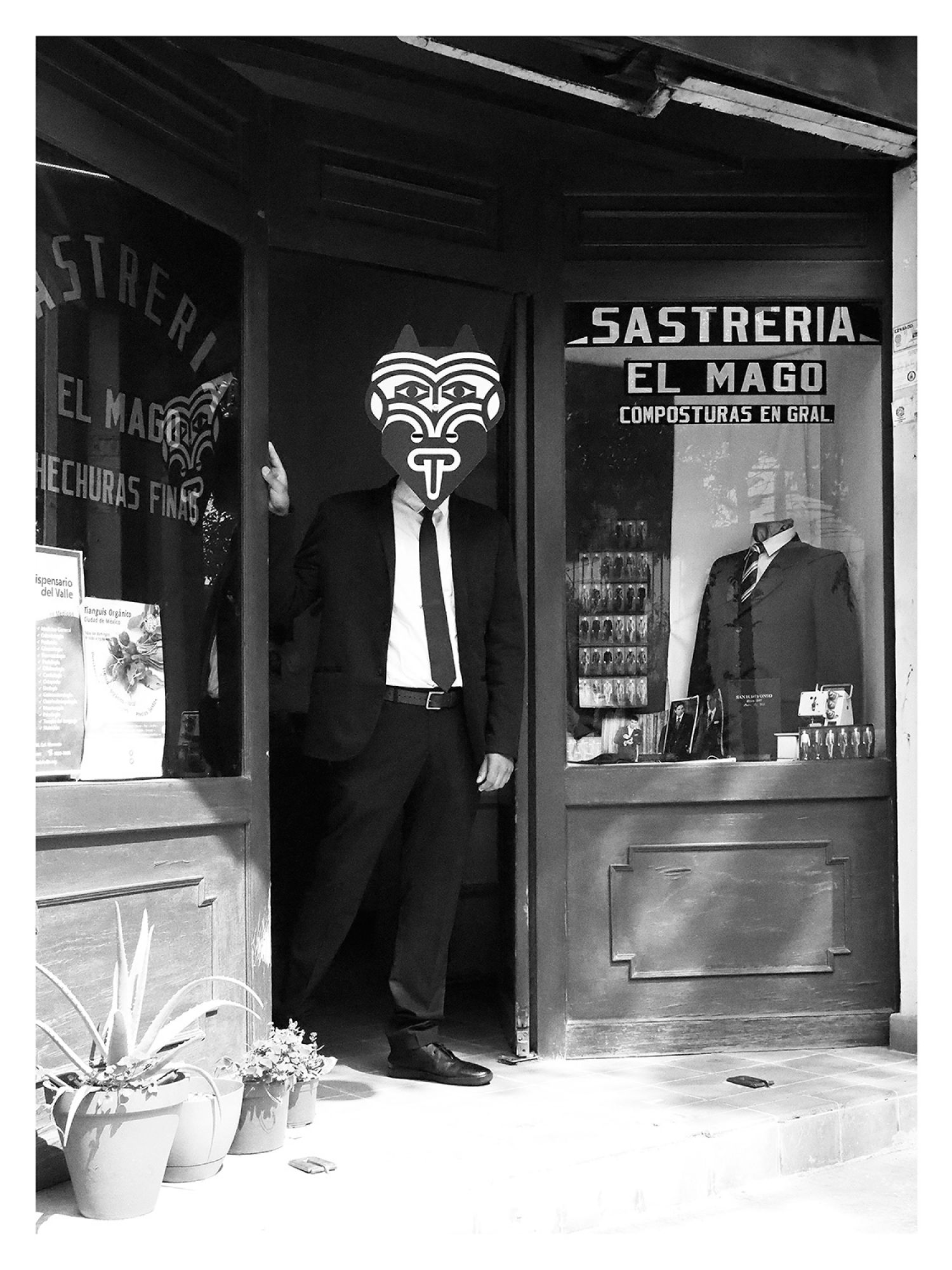

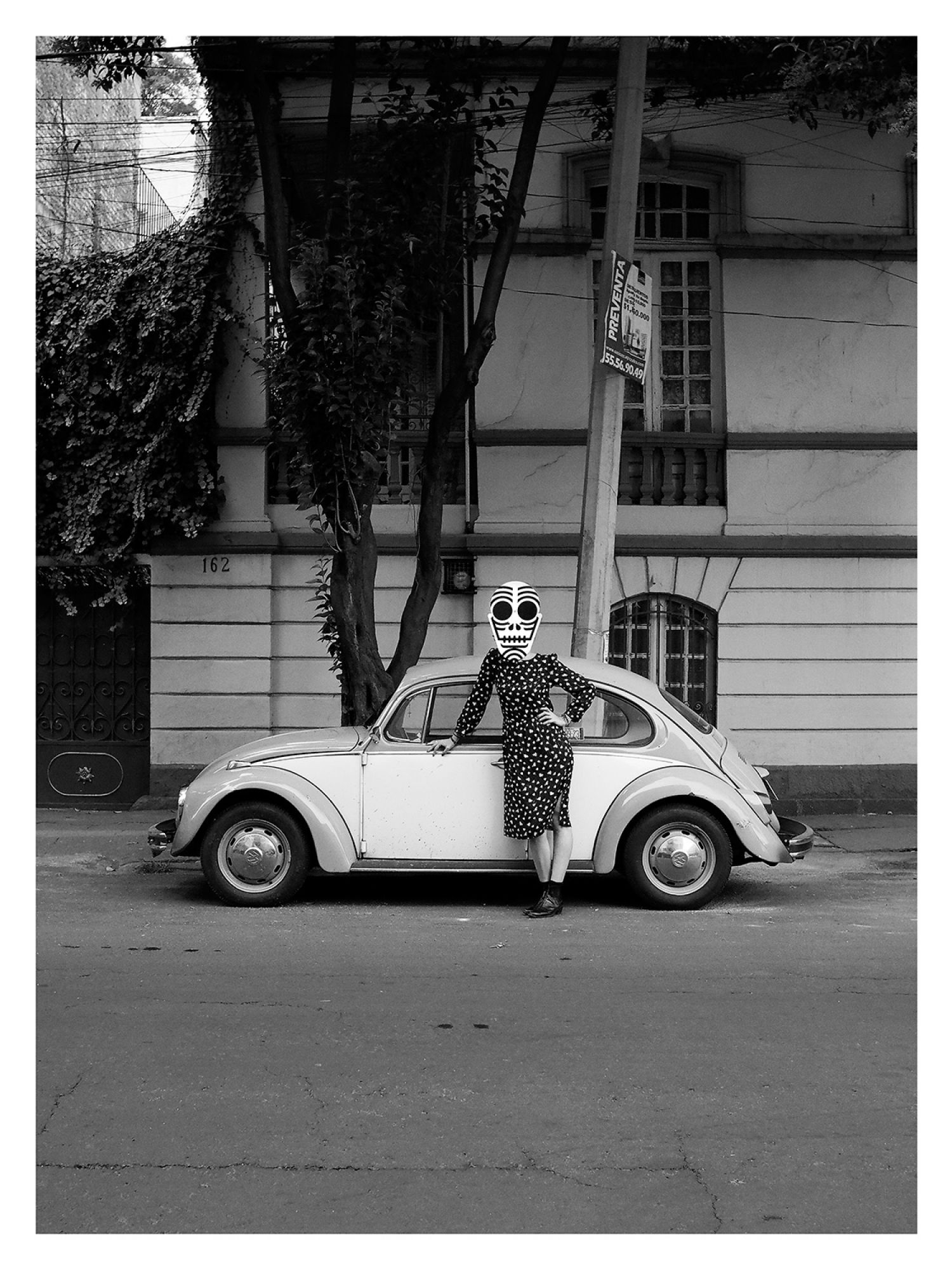

The cult image of the «alien» portrait, a skinned face with flesh in decay, that resembles some kind of robot, has come back, more actual than ever, in the form of an unwanted giant billboard. Created by the «lowbrow» pop illustrator, Mitch O’Connell, and supported by crowd funding, the panel was denied display permission and no company in the US accepted to put it up. Mitch O’Connell, contacted his Argentinean friend, the graphic artist Jorge Alderete, who lives and works in Mexico, and this is how the billboard travelled from Chicago to Mexico City and was successfully installed for a month (July 2017), above a highway. Alderete replicated the «alien» mask and shot some images to keep artistic samples of the event.

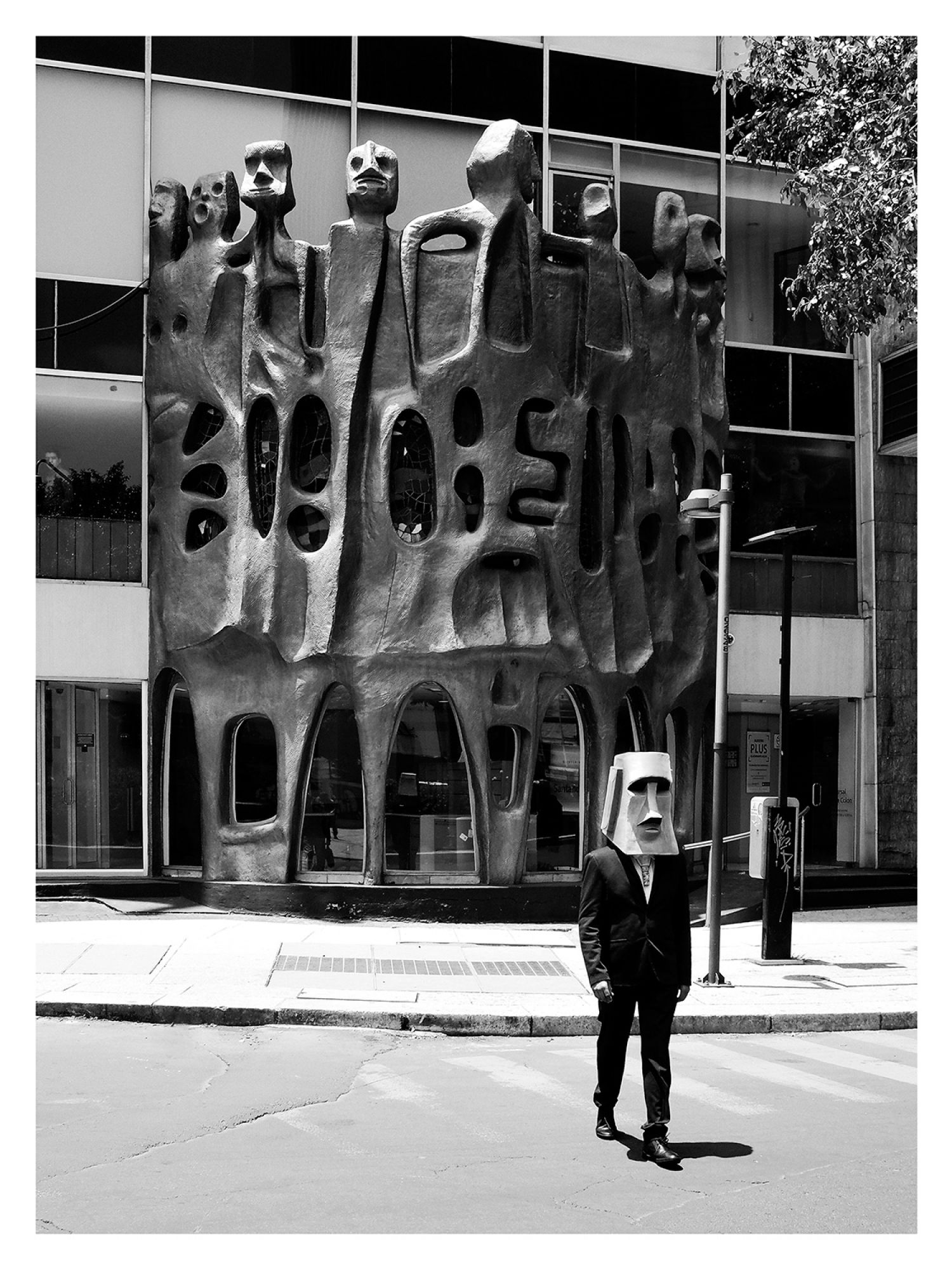

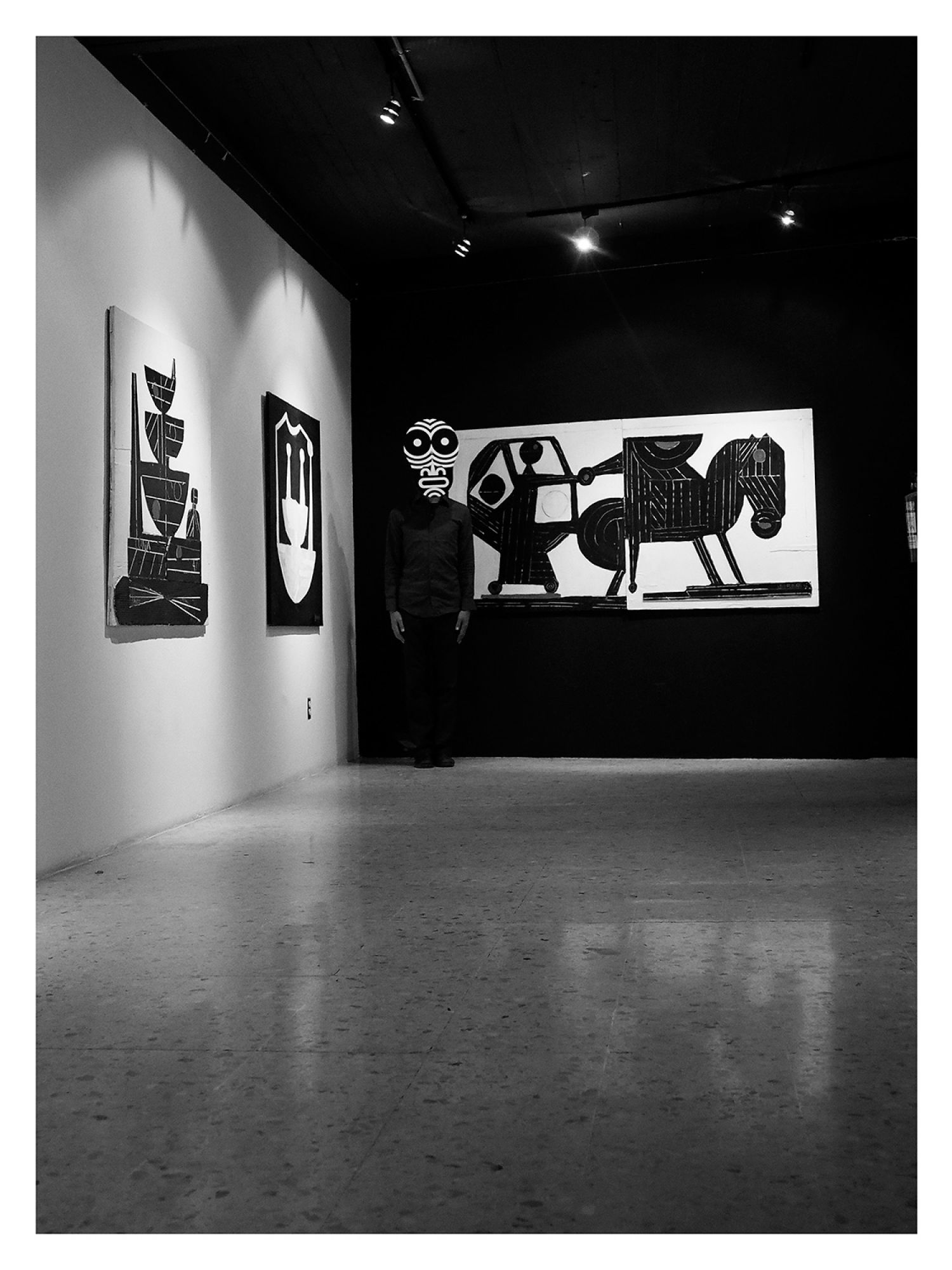

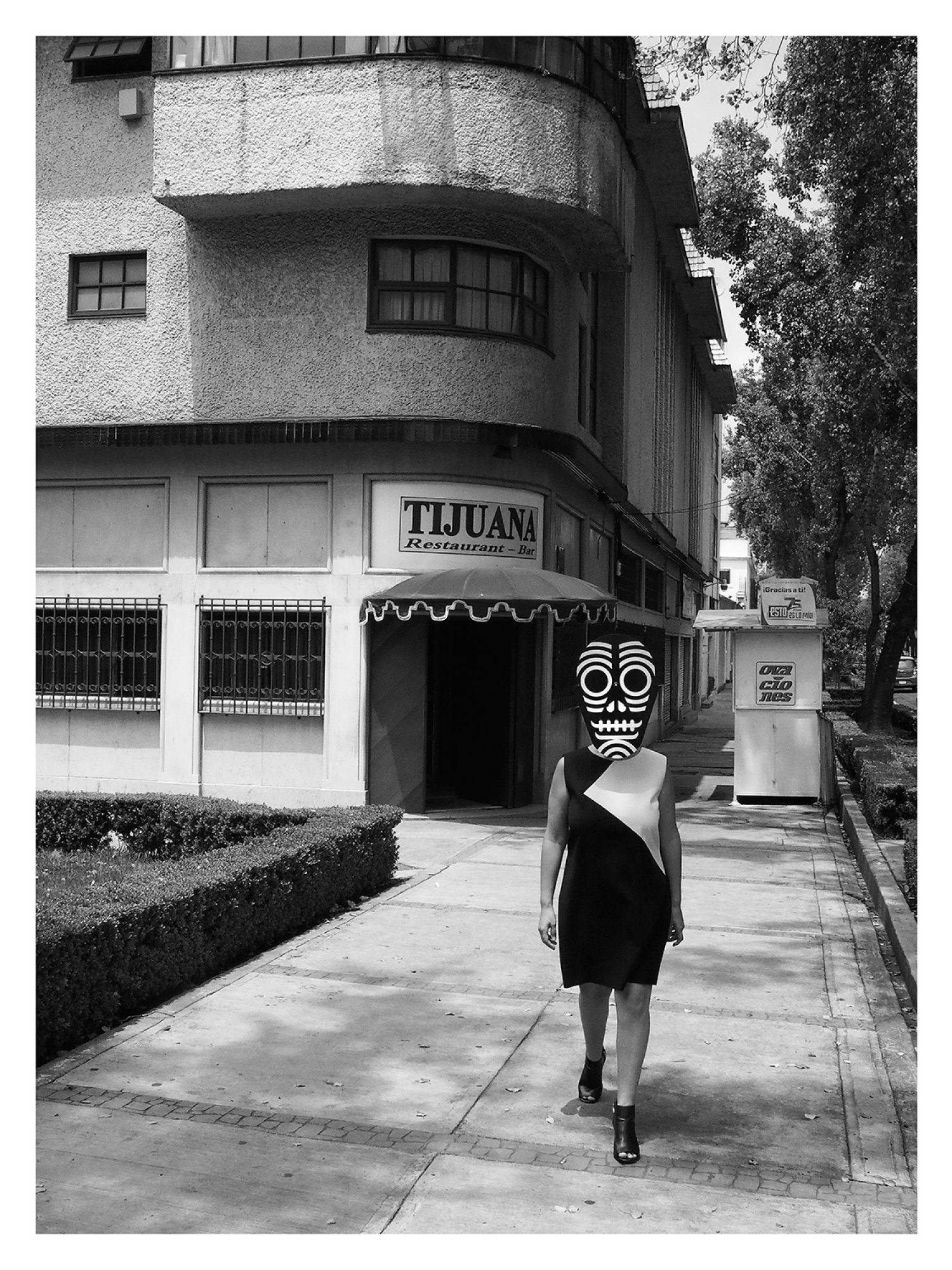

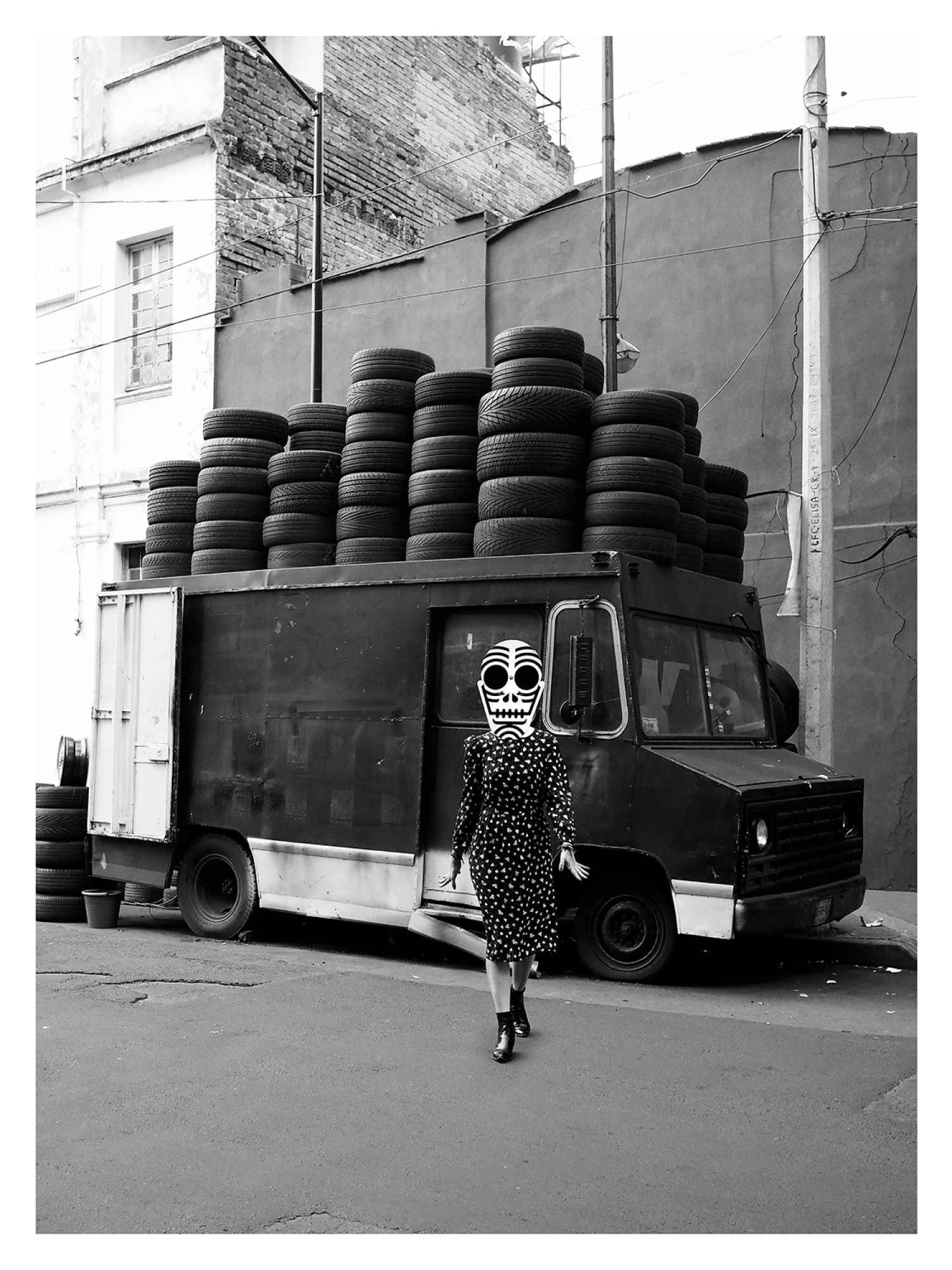

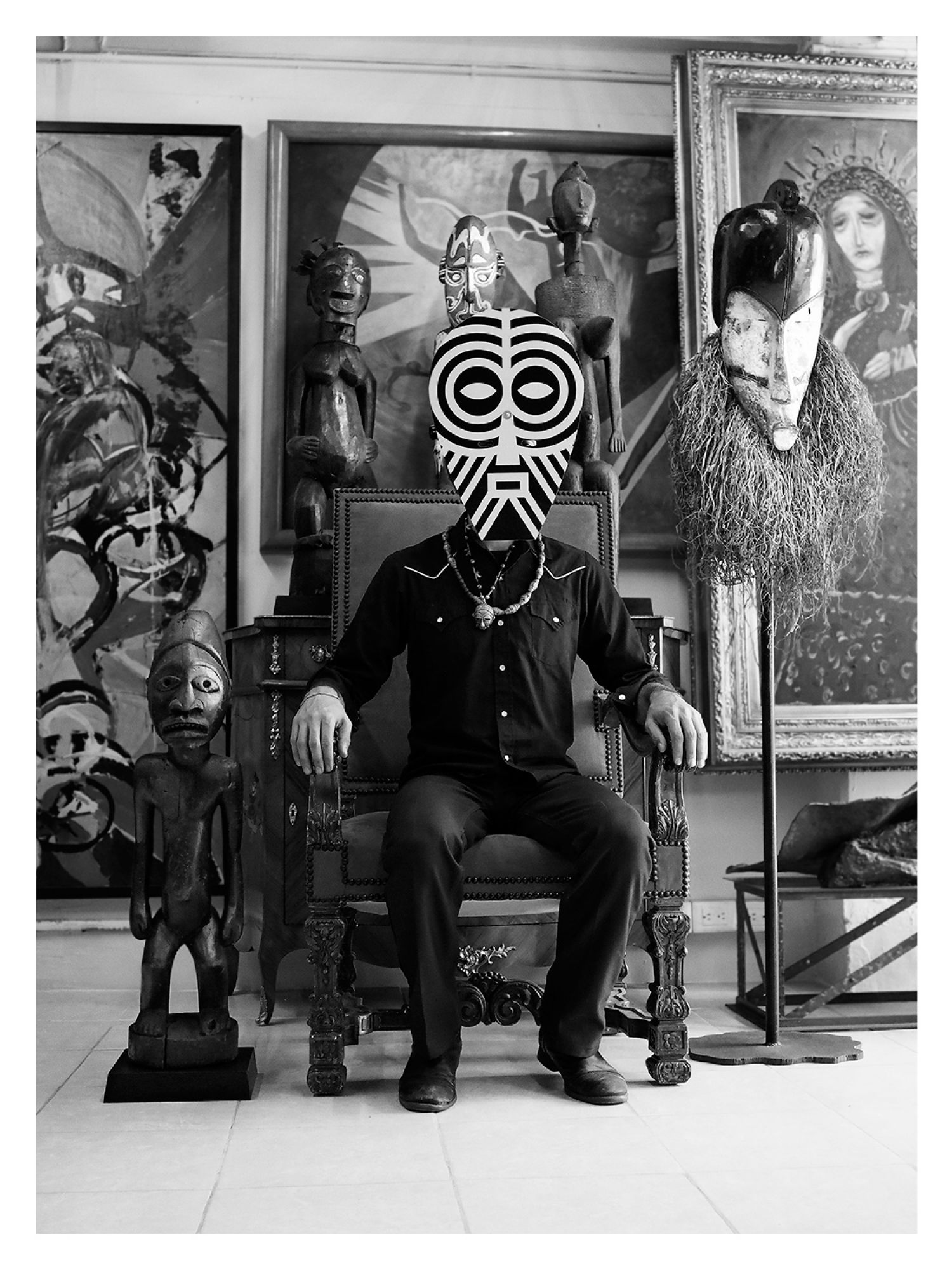

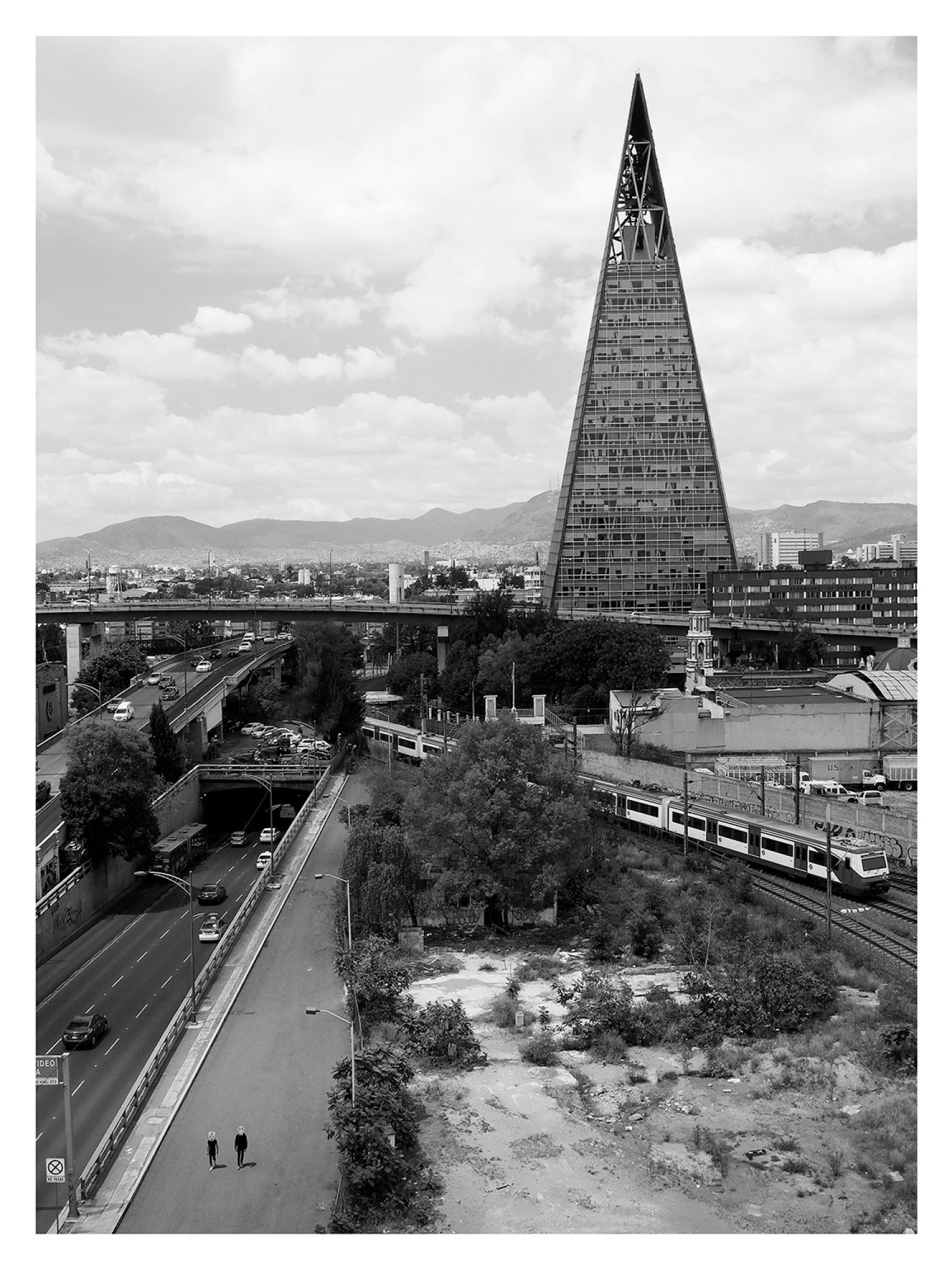

The result is much in tune with his new (and first) photographic mask series, even if the context and the mask iconography are completely different. What do the photographs selected for this Wrong Wrong issue have in common? Is it the anonymity of the subjects? Is it this peculiar uncanny effect and the fascination they produce? Is it the contrast that is staged between banal day-to-day life scenes and the emergence of these unexpected faces surging from no one knows where?

The masks refer to other dimensions that open a gap, a fault in the ordinary and aseptic daily life. This gap is some kind of deep unconscious knowledge disruption, which reveals more than it conceals. In They Live, the ugly faces appear to be the real faces hidden behind ordinary human ones. Seeing the intruders as they really are, as some sort of strangers to human race, implies an act of lucidity and a leap out of the well set up illusion display. If we repeat the concept, the unexpected «sacred» Moai and Mexican masks that appear in familiar urban circumstances could also be perceived as the true faces of these ordinary people. While standing in their living room, in front of the local coffee shop, beside works of art or walking out of the museum, something greater, indescribable and serendipitous is happening. The masks operate a kind of magic trick. All of a sudden, the holders are put in relation with extravagant and mysterious symbolic and mythological «death and life» rituals. The presence of the masks opens a strange continuity between contexts that have absolutely nothing in common. The metamorphosis of the ordinary and the banal into something ambiguous and dreamlike is acted.

The process recalls the Warburgian Nachleben concept, which aimed to point out the phenomenon of the emergence of images and motives in new spaces and times that are not linked to the older ones where they were previously active and significant. As they reappear in an afterlife or survival impulse, their meaning has changed. Thus, the ambiguity and the uncanny effect of Jorge Alderete photographic scenes come from the fact that the masks, far from their celebrations and ecstatic trance contexts where they often personify invisible entities, inducing out-of-body states of mind, appear to be completely assimilated and digest by the conformity of day-to-day life and by the compliance with the conventional surrounding standards. The masks themselves are sanitized, prettified, overly aestheticized. As a matter of fact, the underground and marginalized creativity always ends up being traded, mass advertised and merchandised.

What is maybe shown in Make America Great Again and in the other photos is how the established capitalism triumphs upon the inner sane rebellion movements as well as upon the most remote and genuine traditions. But the irreducible and singular Ganz Andere experience[1] – the sacred one – always threatens to manifest itself and to explode in any context, at any moment, even in the most extinguished and corrupted ones. As the process of going out from ignorance and blind submission to real and deep knowledge is the sacred experience of resistance displayed in Carpenter’s «B» movie, the liberating awakening to the multiple and otherness can spring up from the standstill and dreadful flatness of uniformity and conformism, like Alderete allows us to see.

Footnotes

- ^ Otto, Rudolf [1917], 1923. The Idea of the Holy: An Inquiry into the Non-Rational Factor in the Idea of the Divine and its Relation to the Rational. Oxford University Press.