Marlene Monteiro Freitas dancing the wild side of Beauty

Katherine SiroisGrotesque has been a constant throughout the history of arts and has taken innumerable forms and features. From the Greek Gorgons to the whimsical frescoes of Nero's Domus Aurea in Rome and the influence they exerted on the arts of the Renaissance, from Leonardo's grotesques to the insolent proliferation of hybrids in the works of Bosch, from the extravagant and clownish character heads by Franz Xaver Messerschmidt to the toothless old women in Goya’s Caprichos and Black Paintings, with their grimaces and ugly faces, up to the troubling portraits of Cindy Sherman, it constantly sprang up. As a category of modern aesthetics, it is rather different from satire and caricature, which highlight the work of the negative to condemn and to rectify it. In a different way, grotesque is generally associated with the transgressive nightlife and the uncanny. Without a shadow of criticism or blame, it relates to transvestites, fools, hybrids, automated or wild figures, bringing out a whole fauna. «The grotesque aesthetic does not condemn what it represents, it is limited to notice the fragility of the boundaries between the human and the animal, the passionate man and the monster, what is beautiful and what is ugly, the good and the bad»[1].

The frailty of boundaries (if any) between inner motions, desires, conflicts or tensions and outer appearance is a major approach of faces in arts. It involves the subtle depiction of the mind's activity or the passions of the heart (equivalent of the emotions in Descartes’ works or of Pathosformel in Warburg). It is now, in the field of live performing arts, brought to its climax by the Cape Verdean dancer and choreographer Marlene Monteiro Freitas.

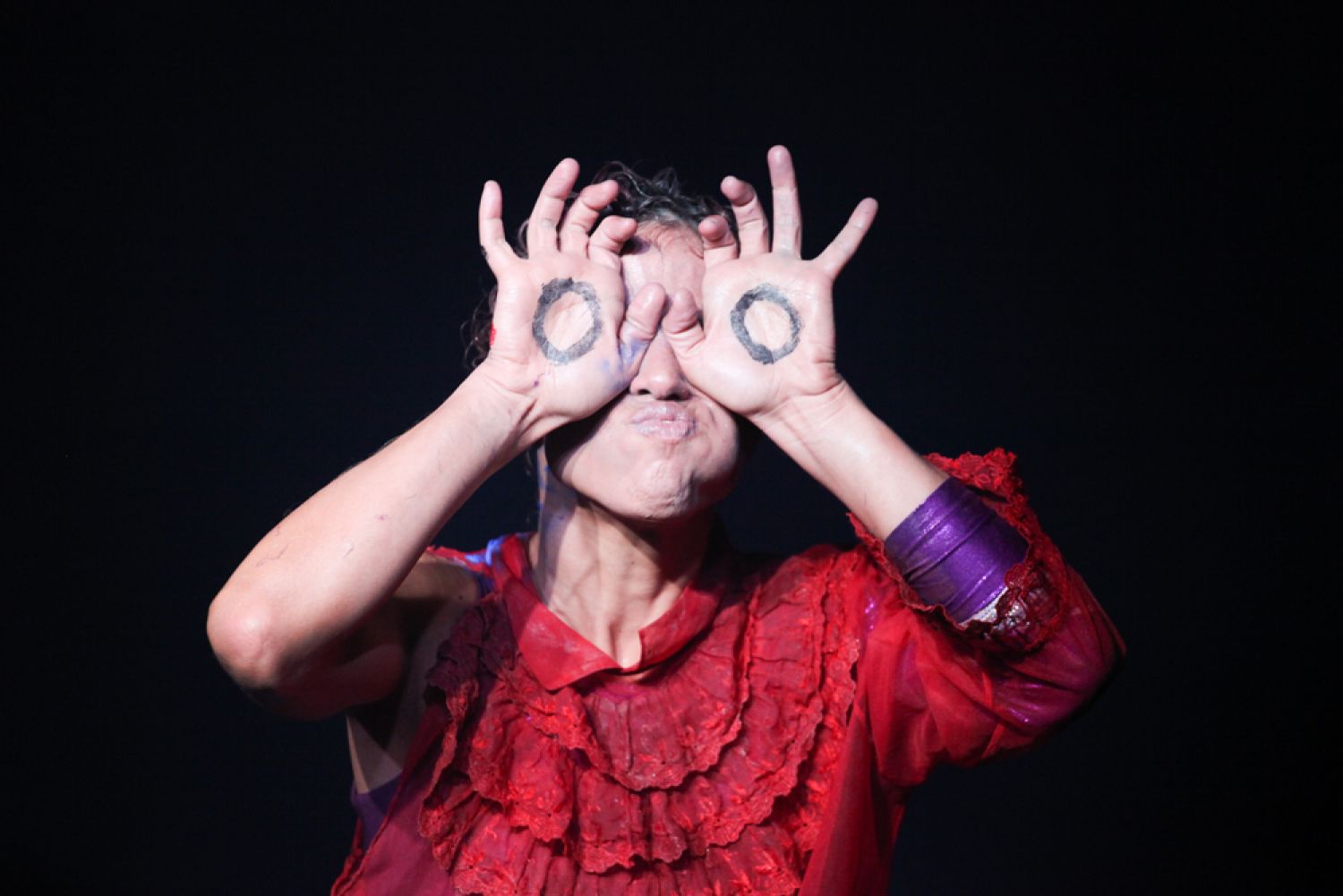

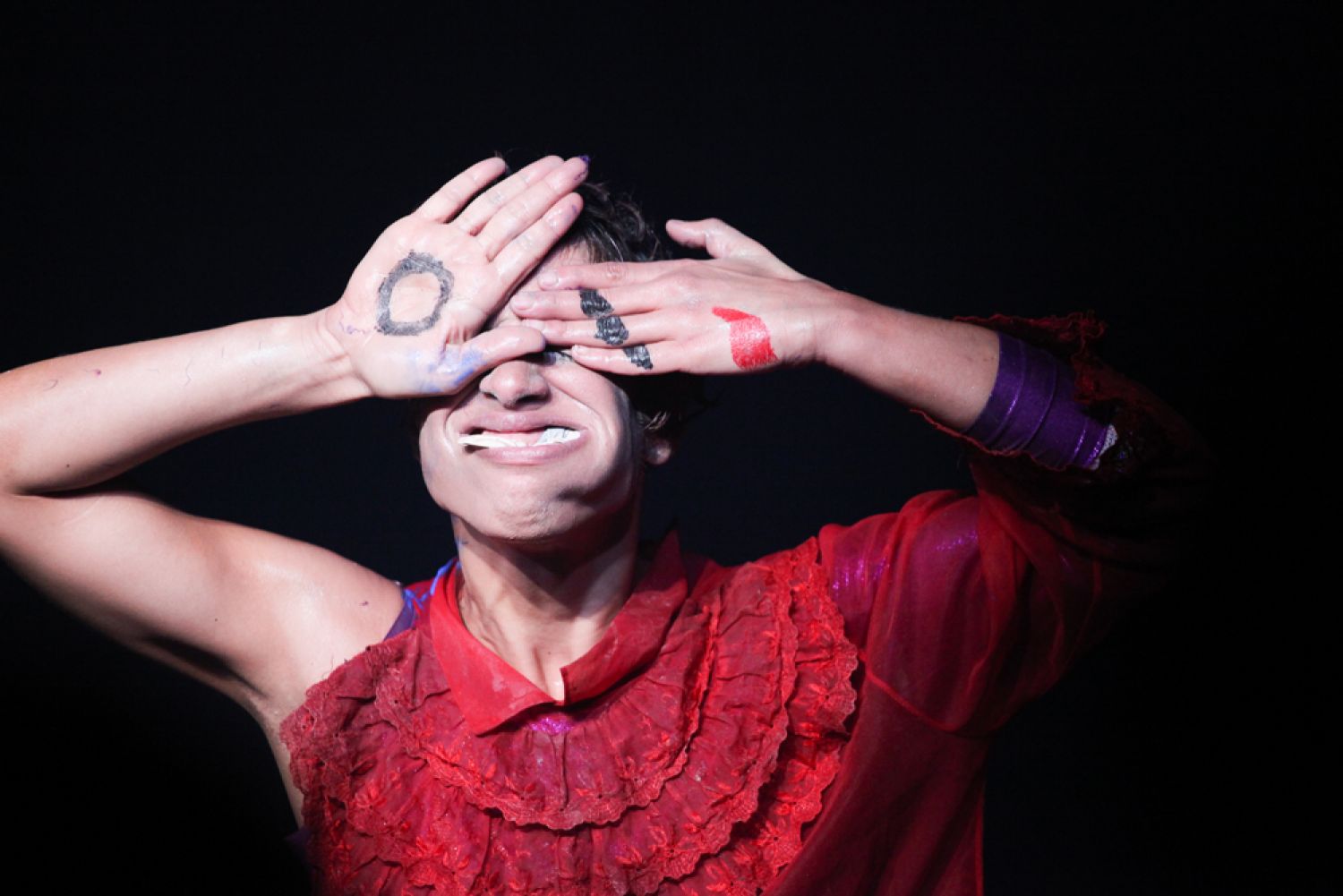

Guintche, a solo show created in 2010, confronts the spectators with an enigmatic and unfathomable character, all at once archaic, kitsch and hyper-contemporary. Alone on stage yet multiple, its body is split into distinct dynamics. At the rhythm of percussion, the hips whirl as a relentless mechanic. The face, on the other hand, devotes itself to a prodigious series of metamorphoses, an infinite multiplication of ‘baroque’ disconcerting expressions. This dramatic density would have nourished the tradition of physiognomic analysis which, according to Lavater, corresponds to the faculty «to make known the inside of man by his outer appearance»[2], today referred to as morphopsychology.

The figure’s facial mimics, in an extreme and permanent tension, are pushed to the limit of the deformed and the bearable. This formal polychromy, which unfolds itself in a raw and energetic expressionism, is simultaneously referring to the carnivalesque frenzy and to some kind of absurd automation. All of this contributes to blowing up the realms of social appearances and of boring conformism. It shakes the banality of conventions and norms and thus reaches a dangerous primeval core, which has the power to raise fascination amongst the audience.

The furious rhythm of the percussions together with the succession of gestures, metamorphoses and expressions seem to evolve towards a state of hypnotic trance where genders, species, identities merge and where «passions» – pride, desire, fear, divagation, pity, despair, suffering – make their way to the outer surface of the visible. Like a glove of flesh turned inside out, it all comes up against the limit of the blind eyes painted on the eyelids of the dancer. Through the excess, the energetic discharge and hubris, affects and passions would thus eventually lose all consistency and become pacified.

Playing on ambiguity and hybridity, Guintche portrays a shapeshifter. Simultaneously distant and close, its presence evokes a powerful, voracious and empty otherness, both male and female, tramp and sorcerer, predator and prey, trickster and puppet, animal and robot. This machine-body, dancing its anatomy to freedom[3], gleaming and overflowing with vitality and convulsions, plays out the exuberance of contrasts and the law of transitions that produces the inevitable passages from an image to another image, from an idea to another idea, from an object to another object, from a figure to another figure, from an other to another other. Objects, like images, ideas, figures and others are deliberately or not assimilated, digested, integrated into the body’s matter, transformed, distilled and discharged in some sort of new idiosyncratic and marginal world’s organization. The dynamism of perpetual becoming in the relationship with the world and with the presence of others takes place because mimetic embodiment just like perception is opened to virtualities and potentialities of actualization.

But what is exactly this roaring silent cry expressed by a gaping mouth that swallows and spews fake pulpy lips, freaky hands, black tainted fingers, tongues and intrusive stuff? Is it a tragicomic mask, a mask of illusions and truths that veil and unveil, an abstract and supernatural being stripped of all glory, hunting some invisible entity with exorbitant eyes that see nothing, or a caricatured tracked ghetto backslider trading wicked gazes that speak nothing? Is it a theatrical play of behind the scenes, a body acting beyond the body? The perceptible expression of an opaque being, the exhibition of a crowded interiority, or more broadly the sacred «horror of life producing and defeating with ease its monsters and miracles»?[4]

Guintche is haunted by the Dionysian figure of the maenad, the ecstatic bacchante who, in the sacred delirium and madness provoked by the communion with the god, tears her preys with bare hands, in a movement of fury, far from the city, the rules and the cultural prohibitions that guarantee the social and political order. This figure has also been developed in her penultimate show, Bacchantes, Prelude for a Purge, created in 2017 at Teatro Nacional Dona Maria II, in Lisbon. The cathartic is indeed a key element of Marlene's scenic work. Frantic imagination operates through free association and creates unexpected passages between forms of pathos. Together with catharsis, the play with free associations allows ties to be forged between her aesthetic and figurative research and dada, surrealist or psychopathological approaches.

In the theatrical outburst of affects and emotions, deeply rooted in the early religious and medical practices, the tendency is to purge, to purify, to set in motion and to put into action. The rituals of trance and metamorphosis, the choreographed disorders and the theatrical representation of the most violent impulses all act as elements of a collective purge, made effective by the mechanisms of mimetic identification. «With Dionysos, the music changes. At the heart of life on this earth, alterity is a sudden intrusion of that which alienates us from daily existence, from the normal course of things, from ourselves: disguise, masquerade, drunkenness, play, theater, and finally, trance and ecstatic delirium. Dionysus teaches or compels us to become other than what we ordinarily are, to experience in this life here below the sensation of escape toward a disconcerting strangeness»[5].

Guintche, like Bacchantes, by acting an exuberant and ephemeral condensation of the existential, emotional and energetic human potentialities and by the dynamism of setting all this into motion, exults in a variation of incarnations, sensations, emotions, which is as demanding and disturbing as it is joyful and liberating.

Footnotes

- ^ I. Barrena, L. Vazquez, «La beauté hideuse des corps ou la dégénérescence du ‘corps naturel’ au tournant des Lumières», Queste n.°7, Saragosse, 1994, quoted by Lydia Vazquez, in Dictionnaire Européen des Lumières, Paris, PUF, 1997, p. 608.

- ^ Michel Delon, «Physiognomonie», in Dictionnaire Européen des Lumières, op. cit., p. 990.

- ^ Antonin Artaud, on the concept of the «BwO», the «Body without organs», from the radio play To Have Done with the Judgment of God, 1947.

- ^ Roger Caillois, «L’enfer de la nature», in Vocabulaire d’esthétique, Paris, Gallimard, 1946.

- ^ Jean-Pierre Vernant, Mortals and Immortals: Collected Essays, Princeton University Press, Princeton / New Jersey, 1992, «Divinity», chap. 11, p. 196.