L’«Objet trouvé» or readymade and its implications: virtuality and transitionality

Paulo Domenech OnetoTo Anita Isabelle Charpentier

Introduction

This paper aims to propose an understanding of the Surrealist notion of «objet trouvé» and Marcel Duchamp’s readymade in terms of two concepts, extracted respectively from Gilles Deleuze’s philosophy and Donald Winnicott’s psychoanalysis. The idea is to begin with brief notes on the context of Dada and Surrealism to then introduce the novelty brought about by Duchamp’s «work» or gesture, in an attempt to show that its negativity actually implies an affirmation of life as difference with consequences, visible in the work of the Brazilian artist Arthur Bispo do Rosario.

It is important to say at once that what is here called «affirmation of difference» initially means that a readymade is neither exactly or merely anti-art nor can it be properly understood as a specific category of Duchamp’s art or of art in general like, for instance, the blue phase paintings of Picasso or the still life. That is why it is important to state that the presence of any of Duchamp’s readymades in the midst of art works aspiring for a place in the museum is bad nonsense. We shall see why. A readymade is rather an object that plays the role of an event, which surely negates art as far as it frequently loses its own eventful character, but much more importantly, it opens up more possibilities for what we usually think art can be, positing, by this token, a return to a practical-existential dimension of creation outside any strict domain.

As a negative event, a readymade affirms difference in a twofold movement: first, by rendering any and every single object (ready-made) able to play the role of a readymade – here the double sense of the term (ready-made, readymade); second, because such differentiation is not taken for granted, but demands investment, although not on the basis of technical artistry. It is the investment of neutralization – taking an object from everyday life «out of the blue».

Yet, «out of the blue» is a term valid to describe the way whereby a ready-made can assume its fundamental characteristic according to Duchamp: its indifferent aspect. Things happen in life without having any value in themselves (good or bad, beautiful or ugly). They simply happen, indifferently. This is the basis. It is not, however, an «out of the blue» that depicts a victory of chance over thought. On the contrary, as this paper will unfold I hope to make clear that some «work» is necessary for a ready-made to become a readymade, for indifference to be «transmitted», so that difference can be re-injected in art and life.

This is the core of the second sense of an affirmation of difference. 1) Any and every thing is potentially art (maximum of different possibilities for art). But above all, 2) each thing that becomes a readymade attains this condition inasmuch as it causes a sense of indifference in favour of difference. We must stick to the paradox and sustain it. The best we can do to «solve it» is to say that indifference is to be produced on the level of our perception for the benefit of difference on the level of a practical-existential dimension (not only maximum of different possibilities for art, but for them in connection with life).

It is precisely this passage from indifference to difference that is here to be explained with the aid of Gilles Deleuze’s concept of virtuality and Donald Winnicott’s clinical notion of transitionality.

«Lost and found»: the objects of Surrealism and Duchamp’s readymades

It may sound an arbitrary distinction, but let us start with the French rendering of readymade as objet trouvé [found object]. Is there a mere difference in translation from one language to another? Let us argue that no. Let us say that, if this specific translation was not «literal», it was not only because of a difference in the terms and their comprehension for each of the languages involved, but also for a deeper cultural-historical reason: because of a fundamental difference between Duchamp’s Dada and Surrealism.

What is an objet trouvé in French common language? What does it designate? It is quite simple. It tells us about lost objects that have been collected to be given back to their original owners. Lost and found. Trouvé is the condition of an object that was lost in the sense of left behind: an umbrella, for instance. But it seems that an umbrella as readymade is still quite different from an umbrella in some of René Magritte’s paintings.

Let us try to find a context to locate the problem at stake. Since the very beginning of the First World War carnage, the anti-art Dada manifestations are in the air, from Zurich to Berlin and New York. As the conflict reaches its climax, in 1918, the Berlin periodical Der Dada proclaims the «death of art», which ultimately meant its radical politicization against war and nationalism as by-products of the logic of capitalism, but also against the harmless and sterile aestheticism of the arts. In Paris, André Breton took part in the Dada meetings and was very concerned with a politics of art. Les Champs magnétiques – his first ‘automatic’ text, published with Philippe Soupault in 1921 – was written in the spirit of Dadaist spontaneity. Nevertheless, as René Passeron stresses, by his emphasis on the power of the imagery and a certain experimental seriousness, one can see that Breton, in spite of all Dada fuss, «never lost hold of the thread which joins his poetry to that of Apollinaire or Reverdy, and to Symbolism. That was why he was soon to break with Tzara and Picabia».[1]

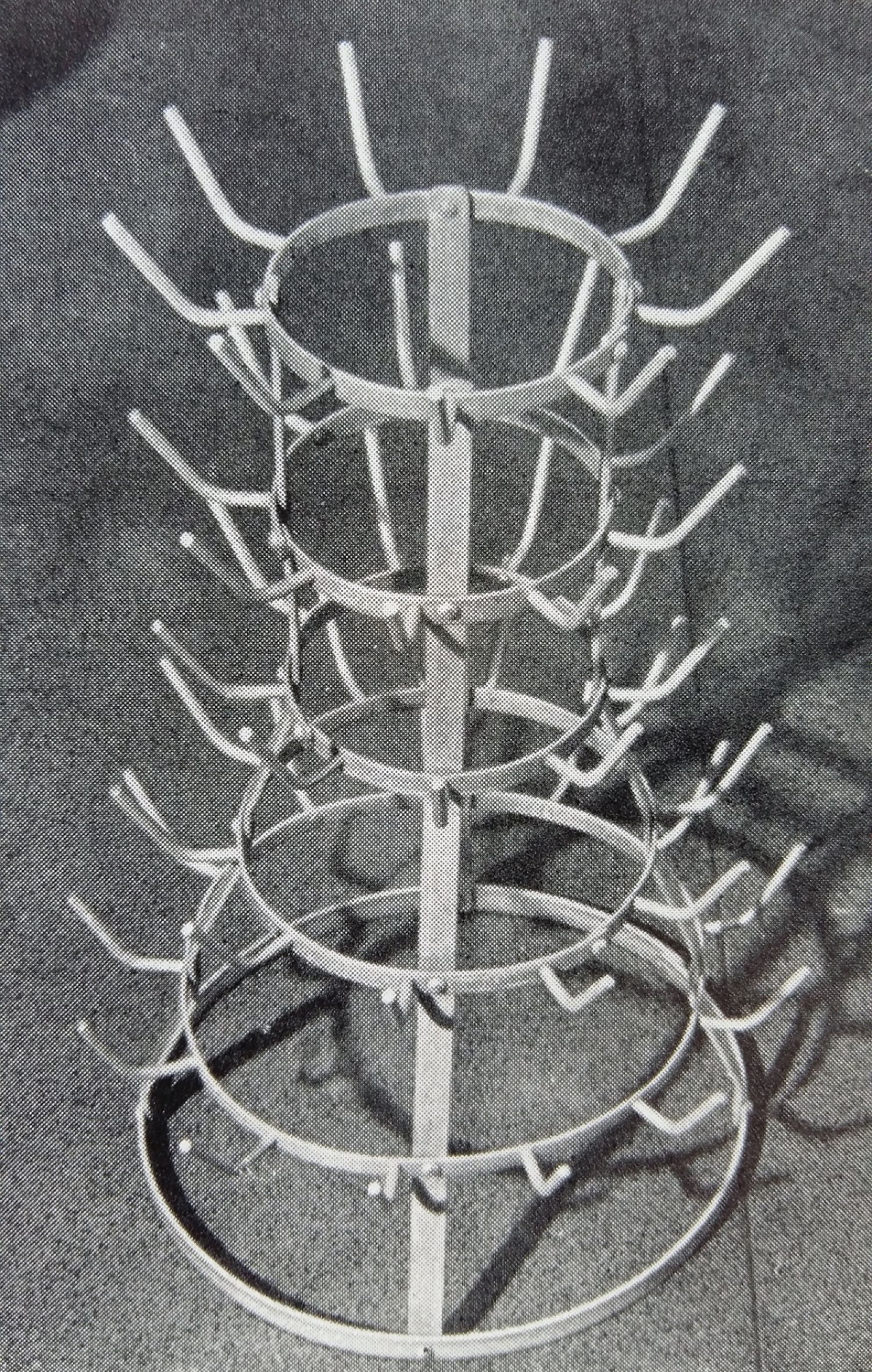

In fact, not only is the first manifesto of Surrealism only published in 1924, eleven years after Marcel Duchamp’s Bicycle Wheel (although this readymade is still not considered as a «pure» one), but also André Breton’s formulations subsequent to the manifestos about the Surrealist object as objet trouvé seem to refer to something else.

We already know Duchamp’s Bicycle Wheel (1913). It is a wheel from a bike mounted by its fork on an ordinary stool. If historians of art do not consider it as the first Duchampian readymade, this is simply because it was built upon a found object rather than being just found in its «pure» indifference[2]. In addition to that, the very idea of readymade had not been put forward by Duchamp yet. He composed it, playfully, as a pleasant gadget. That is why some can also consider it as the first kinetic sculpture more than just a readymade[3].

Now, could that correspond to the idea of an objet trouvé?

It is true that Breton came to assert a merging between his idea of a Surrealist object (to be found in dreams) and Duchamp’s readymades. In the Dictionnaire abrégé du surréalisme, for instance, he presents the following definition of a readymade, under the name of Duchamp (the entry comes signed with Duchamp’s initials, M.D): «an ordinary object elevated to the dignity of a work of art by the mere choice of an artist».

«Elevated to the dignity of art» is already a quite problematic expression to describe Duchamp’s work or gesture. In a way, of course, yes. Duchamp could have signed that entry in the dictionary (he probably did not). After all, the readymades made their way into museums – no matter how –, and museums are the place for art works. Also, by repeating that he was «interested in ideas, not in visual products»[4], Duchamp paved the way for the later idea of conceptual art, of something «made» to be thought rather than merely experienced on the retina. He excavated a new field for the arts. Therefore, in a sense, he indeed «elevated» simple thought experiments to the dignity of art. On the other hand, it is not an elevation at all since a readymade is a whatever object, selected precisely because of its «visual indifference», on a non-value basis. Instead of an «elevation of ordinary objects», would it not be more appropriate to focus on the ideas and spaces of art, and talk about a «lowering»? It is rather the conceited and detached domain of the arts that seems to be lowered or at least placed on the same level of ordinary everyday things.

In the same key, it is true that the lowering may also mean an elevation, although not at all because of a museum effect bestowing a kind of aura to ordinary objects. The elevation is now a possibility that emerges outside the institutionally recognised space for the arts. It is life that claims to be elevated without the necessity of museums insofar as it becomes a potential space for artistic experience – both as space for creation and for being affected. It all goes a bit in the sense of Brazilian poet Manoel de Barros’s idea of greatness as ultimately residing in minor things that pass unnoticed. His book published in 2001 bears this telling title: Treatise on the greatness of tiny things, implying what I have named elsewhere an ethics of the minimal[5].

By insisting on the idea of an elevation of ordinary objects, some art lovers could finally come on drawing conclusions about an attempt from Duchamp to recognise the aesthetic value of ordinary things. The readymade was understood as any natural or discarded object found by chance and held to have such aesthetic value, when there was never such a claim from Duchamp. On the contrary, the readymade’s function was precisely anaesthetic. Duchamp himself ascribed this clear negative goal to his work: to avoid the formation of a taste. He stressed, moreover, that Dadaism was mainly purgative[6].

On the other hand, the idea of an «elevation» fits well enough when one looks into Breton’s artistic trajectory. Despite their discrepancy, in both of his Surrealist manifestos (1924 and 1930) the term «surreal» echoes a sense of an elevation, notwithstanding that the French prefix «sur» was in no way referred to pure fantasy or a mysticism denying reality, but rather to a higher reality intrinsic to thought albeit neglected by over-controlled forms of consciousness. In this sense, it is clear that Surrealism owes a great deal to Freud’s psychoanalysis with its strategies to gain access to our unconscious activity. Thus, in the first manifesto, the higher reality is «the true functioning of thought» devoid of transcendent aesthetic and moral preoccupations. Surrealism aims to express it by means of pure psychic automatism. As for the second manifesto, it appears as a complement, but by asking about the moral competence of the artists to turn their modes of expression into concrete social action, Breton once again seems to evoke an ideal of elevation and dignity to artistic creation. Antonin Artaud’s outcry to put an end with masterpieces can finally be seen as the most powerful resistance to Breton’s pretensions throughout the 20th century[7].

Yet, after all, what was «lost» and must be «found» in Duchamp’s readymade and in Breton’s Surrealist object? Before getting into a few more details of Breton’s approach of objects, let us make use of a parallel between two classical films in order to clarify the distinction I am trying to propose.

I am referring to Luis Buñuel’s That Obscure object of desire (1977) and Michelangelo Antonioni’s The Adventure (1960) where two women seem «lost» to their respective lovers. In the first case, Conchita is forever lost for the respectable lovesick middle-aged man Mathieu. She is lost as object of desire. After all, desire functions according to an obscure logic; hence the title of the film. As Mathieu finds Conchita more approachable, she turns into a different, unattainable woman. Antonioni’s The Adventure operates according to a different cartography. Anna actually disappears from her lover Sandro after a quarrel during a visit to an island near Sicily. However, she will never be found on any level of reality whatsoever, probably because her place in Sandro’s life was already empty from the beginning. Anna is lost as everyday object. It is a fundamental theme of Antonioni’s filmography: the way lovers strive to remain together for nothing but habit, inertia, and fear of being alone. That is the reason why another woman (Claudia) is rapidly courted by Sandro to take Anna’s place, of course unsuccessfully in terms of the possibility of a real bond, as the film’s last sequence indicates.

Perhaps this short interlude in my paper allows a better understanding of a contrast between two modes of «losing and finding objects». Dada and surrealism have both claimed for a «loss» of the objects so that they could be «found» – created, re-created. In Surrealism, the object is to be «found» as object of desire by means of psychic automatism and similar devices. For Duchamp, it is to be «found» as an object of everyday life by means of a double negation to be discussed further up.

The Surrealist object is like Buñuel’s Conchita: lost as an object of desire that has been denied to us; to be found in our unconscious activity, in dreams that ultimately express the unattainable. Freudian psychoanalysis is the best ally here. Instead, Anna – Antonioni’s character – plays the role of a readymade: lost in the sense of an object of everyday life that was emptied in its banality; impossible to find, except by means of an affirmation of difference implying a strange form of negation.

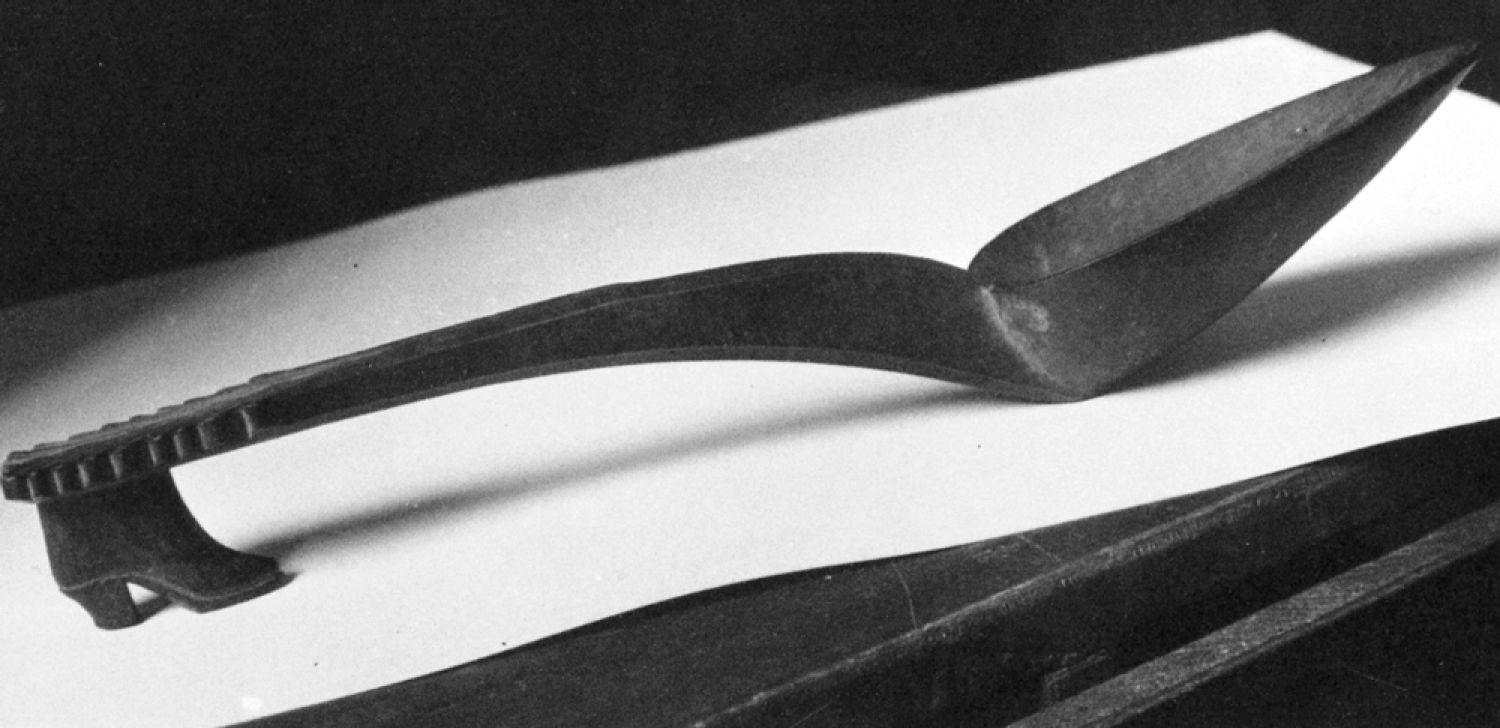

As for Breton’s idea of objet trouvé, it is not necessary to speculate much about it since his ambitious text «Equation of the objet trouvé», originally written in 1934 for a Belgian journal (Documents 34), gives us a good general account of the issue. It is meant to work as a sequel of the two key poetic endeavours by Breton: Nadja (1928) and Communicating Vessels (1932). It constitutes a remarkable meditation on an essential surrealist theme, that of encounter and «objective chance» (which is also the subject of Mad love, 1937, where the text would finally be included). Breton narrates the «encounter» of two objects: first, a mysterious mask, found during a walk in the flea market with his friend, the sculptor Alberto Giacometti; second, the piece acquired by Breton himself, a large wooden spoon of peasant execution. He describes the two objects, wondering about their function and bringing them close to a recent sculpture by Giacometti. He then concludes that it is a case of «objective chance», the objects being symbols of their respective purchasers’ hidden desires. The finding of the two objects fulfils the function of a dream inasmuch as it frees the individual from paralyzing affections.

Everything seems quite clear. What was «lost» (denied) and must be «found» (symbolized) is an object of desire. It speaks of our unconscious and is supposed to purport a meaning. That is the situation of Conchita in Buñuel’s That Obscure object of desire. She probably discloses Mathieu’s impossibility to love (meaning). It does not really matter. In Breton’s Nadja too, the absence of the object of love offers the character (André) greater inspiration than does her presence. This is not necessarily an argument about idealization, neither is it a too simple assertion about a so-called truth of desire as lack. It is absence as a mobile for creation. Desire propels creation, and Nadja’s absence becomes important insofar as it permits her to live freely in André’s mind (in his dreams), allowing creation without the strict boundaries of reality as usually conceived. The key word for Surrealism is dream, not lack. The found object is therefore a dream object able to revolutionize reality from within. No wonder Surrealism was to be strongly revisited during the 1968 barricades in Paris.

Since Nadja, Breton displays his obsession with the idea of objects that one cannot find anywhere else outside our dreams. The Surrealist object is precisely that: an object of desire, the product of a dream. The spoon found by Breton symbolizes a hidden desire and propels creation as long as it is also part of a dream. Yet, it is Breton’s affirmation that any wreck within our reach is to be regarded as a precipitate of desire that mingles his efforts with those of Duchamp. One concludes that fragmented and useless objects deserve to be elevated to the dignity of a work of art. It makes sense within a Surrealist frame: after all, all objects can correspond to dream objects. Their aesthetic merit lies there, insofar as they reflect a hidden desire and allow one to dream.

It remains the necessity of a more detailed exploration of Duchamp’s readymades in this lost and found context. Right away, there is a paradoxical situation: they are «lost» and «found» without any apparent transformation, as objects of everyday life, at least without any second layer of meaning to take into consideration. Nothing appears concealed. There is no meaning to emerge. What was aesthetically empty seems to remain aesthetically empty. Nevertheless, as suggested above, Duchamp’s gesture performs a strange invisible kind of transformation from ready-made to readymade by means of a double negation. What is this double negation? Why is it essential to think of the readymade as actually «found»?

The double negation

Duchamp’s «lost» object was never «lost» in the sense of an object of desire. It was never «elevated» to any special dignity either. Never was his intention to ascribe to one of his readymades any other type of aesthetic merit whatsoever: originality of the artist’s gesture or rarity of the object found, for instance.

It was in a short and insightful essay («On Duchamp», 1961) that Mexican writer Octavio Paz put forward the hypothesis of a double negation in order to better understand Duchamp’s readymade. A readymade would be a two-edged knife, cutting out tastes and institutions on the one hand, and boundaries on another. Let us follow the core of his argument as it permits to mark the singular manner whereby affirmation can come to be radicalized in the arts afterwards, as it appears in my final example (Bispo do Rosario).

The first negation was evident from the beginning, prone to all exaggerations and eventual misunderstandings. A readymade negates art, albeit in a quite specific sense. It negates art as far as it frequently loses its character of event, ending up valued on the basis of habits of taste and social conventions – the readymade is therefore «active criticism: a contemptuous dismissal of the work of art seated on its pedestal of adjectives»[8].

Paz is talking about Duchamp’s gesture. The readymade is a non-art object, as Duchamp himself stated at several moments. It is so because of a gesture. An arbitrary gesture – at this point Paz employs the quite inappropriate term «gratuitous», but the choice is not of any object whatever (thus the paradox of having to pay attention and find what is indifferent to us). Still, Paz adds an important note: the arbitrary gesture of the artist converts anonymous already made objects (ready-mades) into «works of art» at the same time that it dissolves the very notion of work. This contradiction reveals that readymades are non-art objects, but they are not anti-art. They are rather an-artistic.

One should probably add another note to stress this point. By choosing an anonymous object to put in a museum or in an art gallery, the artist intends, pretends or contends to be creating something. In all three cases, art is present. Duchamp is actually contending, i.e., saying something about art and life. There is nothing anti-art in the gesture, at least not in the sense of something against creation. The thing is that creation now lies elsewhere, in thought («I was interested in ideas, not merely in visual products»), or it is a game, or it is life itself. At most, it is anti-art in the mere sense of Dada politicization («art as form is dead»).

The idea of readymade is therefore essentially an-artistic. It is the first negation. Despite the obviousness of this understanding of Duchamp, it remains essential; otherwise, people may still insist on looking for the sensible qualities of a readymade when the point is precisely the opposite: how to deviate our attention from them. For the rest, as Paz concludes, readymades do not postulate a new set of values. Yes, there is no program for the arts, no manifesto, not even a hidden thesis about history of art as a whole. Duchamp is not Hegelian.

In short, the first negation is a critical action. According to Paz, it can be divided and presented into two stages: intellectual cleanliness (criticism of taste) and, as a corollary, attack on the very notion of work (the question of artistry). We move from the sphere of reception to that of creation. Aesthetics and poetics. A gesture for the spectator, and another one for the artist. One for Kant, another for Aristotle.

Duchamp’s attack on the nominal concept of art is not as violent as many others’ before or after him. Yet, it has proven more effective. Paz argues that this second stage (criticism of art itself) sums up to an attack on artistic equipment. This equipment turns out to be insignificant. Perhaps his argument runs too fast. What does he exactly mean by insignificance?

The question turns around the controversial and unavoidable problem of form as a means by which matter becomes «matter of expression». «Retinal» art is ultimately based on clichés in the most radical sense of the term. As Gilles Deleuze puts it in his fascinating reading of Bergson[9], a cliché is a sensorimotor image of something, always partial, based on what we need, want or are able to bear. In short: we never compose an image of things in their wholeness. Duchamp is roughly pointing to the fact that art became too poor because too detached, too concentrated on the retina – art as a domain of clichés. From the side of reception: a trained retina. In terms of creation: too formalistic, i.e., based on certain fixed devices, too concerned with producing specific types of effects.

It suffices to think of nowadays, a century later, to grasp how up to date Duchamp can be. At any rate, a new paradox emerges here: art, which was meant to contest clichés, became itself the realm of clichés; it may be necessary to break this aesthetic sensorimotor scheme with a different kind of cliché (the readymade). Actually, in any age dominated by clichés it will always be necessary to lay hand of procedures like Duchamp’s. To use Paz’s terminology again: as the equipments of art become insignificant and art techniques formalistic or separated from expression, thought is put aside and becomes unable to question habits of taste.

What are the results of the retinal trend denounced by Duchamp? Well, such a reduction of art to sensation is finally conservative and seems complacent with a social hierarchy implicit in the domain of the arts. Here, Duchamp also helps us to anticipate an important theme of Pierre Bourdieu’s sociology of the arts (a critique of charismatic ideology of creation as we see in his Rules of Art).

Nevertheless, it is the second negation discussed by Paz that matters the most for my interests. It concerns the questions of neutrality and anonymity: «not only the gesture but the object itself is negative»[10].

Neutrality and anonymity define the object, its new nature. According to Paz, the readymade confronts the formalistic insignificance of the arts with its neutrality, its non-significance. How so? Once detached from its original context, the ready-made suddenly loses all significance. It is converted into an object existing in a sort of vacuum. It is the vacuum of being out of place. On the one hand, the ready-made lives in the territory of the arts, but it appears identified as belonging to another domain. It was «found» as an object of everyday life in the museum just as another Dada provocation. Our commonsense never gets tired of repeating it. On the other hand, however, it cannot be really «found» there: «The act of Duchamp uproots the object from its significance and makes an empty skin of the name: a bottle-rack without bottles».[11]Our commonsense must heed to that: emptiness. We are finally cast back to my «lost and found language». The ready-made is fatally «lost» in the sense of emptied (like Antonioni’s character, Anna, in the film The Adventure): a bottle-rack without bottles, Anna without any real connection with Sandro. The readymade was supposed to be «lost» as a bottle-rack (an object of everyday life) without bottles. It is supposed to be «found» as out of place («hey, I do not belong to museums, but to pantries!»). Likewise Anna: «lost» as Sandro’s wife who unfortunately disappeared during an excursion, she would be «found» as a missing wife. Nonetheless, things do not work like this. Neither the bottle-rack is waiting for a bottle nor can Sandro find or even replace Anna. The bottle-rack remains there, and no one must put a bottle on it. Sandro’s desire remains lost, and Claudia is helpless.

In order to be «found» the ready-made has to undergo, really and completely, Duchamp’s process of double negation. It must become a readymade. Paz observes that the loss of significance of the object (ready-made) and its fall in the vacuum (readymade) does not last long: «everything that man has handled has the fatal tendency to secrete meaning. Hardly have they been installed in their new hierarchy»[12]. Hence, the need to «rectify» the ready-made: injecting it with irony to preserve anonymity and neutrality. Art must maintain a state of permanent revolution to keep resisting habit and institutionalisation to become art.

Let us call the change in the nature of the object (Paz’s second negation) an «invisible transformation»: art is not beauty, fascination, or whatever without being, first, resistance to an imprisonment of life into moral and political models of sensation. Anonymity and neutrality play a great role to keep this resistance. Besides, without «rectifications», Duchamp’s idea of readymade is no longer able to ensure anonymity and neutrality. Art is always in danger. It is its very nature. Duchamp knew that. So did Artaud.

The anonymous character affirmed by means of the second negation promoted by Duchamp’s readymade helps to take us outside the already too common sense debate about the artist’s signature. An artist turns something into art by signing it. We already know that. There seems to be no doubt about that. As Paz admits himself, the object is anonymous; the man who chose it is not. It is the gesture of signing. The audience asks, allegedly looking for the artist’s skills, «Who said this or that?», «Who made it?». It is the old argument of authority – ad hominem.

Is it not already a second gesture?

Yes, because the gesture that counts is not the gesture of signing, but the gesture of «creating» the readymade. The key point comes with the excellent comparison between two types of signature, made by Paz:

«Roger Caillois points out that certain Chinese artists selected stones because they found them fascinating and turned them into works of art by the simple act of engraving or painting their names on them. (...) [The Chinese artist] inscribes his name on a piece of creation and his signature is an act of recognition; Duchamp selects a manufactured object; he inscribes his name as an act of negation and his gesture is a challenge».[13]

There is, in the first case, the signature of the person who «knows», who «has taste» to select. He is deemed as entitled to choose the object, a readymade expert. But there is a signature where taste plays no role at all. It merely plays an institutional role. In an article written thirty years ago («The Crux of minimalism», 1987), the art critic Hal Foster has put the emphasis on that aspect to sustain an argument about an essential break with late-modernist art, preparing «postmodernist art» to come. Fortunately, he goes beyond that. He also recognises a way in which what he calls transgressive avant-garde (Duchampian Dada, Russian constructivism etc.) can be read as a «return» to modernism, all in spite of what seems his prejudices about modernism, arbitrarily associated with the formalist endeavours of an art critic like Clement Greenberg[14].

Agreeing with Foster, one can say that the institutional nature of art has been largely exposed after Duchamp. But anonymity means much more than that. Anonymity goes with neutrality. An anonymous object in the museum primarily means that our geniuses of creation, together with their objects, are less important than what lies beyond them. And what lies beyond them? Their relationship with the world, nature, cosmos, life... Anonymity then serves to neutralize the already too codified and demarcated (Deleuze and Guattari would say, too «territorialized») spaces[15].

Thus, if the presence of Duchamp’s readymades in an art museum may seem bad nonsense, it is precisely because its function is negative beyond the merely institutional. Of course, its presence is important and legitimate inasmuch as it challenges our perception and the museum, curators and all institutions associated. It is Paz’s first negation: intellectual cleanliness (criticism of taste) and attack on the notion of work (criticism of artistry). However, anonymity and neutrality challenges practical-existential boundaries much more than just taste and institutional boundaries. In fact, the readymades deserve to be either at the exit or at the entrance door of the museums, as reminders of an outside related to the objects themselves, to our relation with them.

Let us return to Paz’ words about Duchamp’s gesture as a gesture of selection, not as a mere signature gesture: he selects a manufactured object; he inscribes his name as an act of negation, and his gesture is a challenge.

Institutions have been challenged. But there seems to be much more than this at stake in Duchamp’s selective gesture. The challenge comes to the following: art finds its own outside, not simply nature or even our wonderful manufactured world of useful and consumption objects. Art finds its limit. At the same time, for the same reason, everyday life finds its limit. The readymade has excavated a space in between the art world and everyday life. The readymade is a two-edged weapon, as Paz asserts, «if it is transformed into a work of art it spoils the gesture by desecrating it; if it preserves its neutrality, it converts the gesture into a work»[16]. In my own words: put in the museum in the same place of other art objects, the readymade loses its power; kept neutral it becomes art. Duchamp, master of paradoxes.

It is at this point that Paz seems to make a mistake, perhaps because of his singular way of conceiving art. Indeed. It is not easy to juggle with knifes. According to him, seen as a dialectical game or as a means of purgation, the readymade would not really be an artistic act after all, but the invention of an art of interior liberation. Buddhism.

Why so? Would not it be precisely the contrary? As an object that escapes categorizations, not artistic or everyday object any longer, would not the readymade be able to put the boundaries inside/outside, interior/exterior into question? Would not it be an artistic act precisely – and a fortiori – because of that? Not an interior liberation, but rather art in the sense of liberation from both interior and exterior, from subjects and objects, from artists and museums.

Artistic acts ultimately consist of challenging boundaries and limits. Duchamp’s readymade can thus appear as virtual in the sense of Gilles Deleuze’s philosophy, or even as transitional in the sense of Donald Winnicott’s psychoanalysis. The readymade has no value as an actual everyday object, but it has no value either as a possible world created through artistic symbolism. Its real value lies elsewhere, in a third domain: not actual nor a mere possibility – Deleuze. It traces a new map: the third area does not belong either to artistic territory or to everyday life as such, although both worlds contribute to it. It is an object able to keep inner and outer reality separate yet inter-related – Winnicott.

Virtuality and transitionality: from Duchamp to Bispo do Rosario

The bewilderment of most of art lovers in our days against the undeniable fact that almost anything can be and has been called art during the last fifty years is well known. An entire book (The Contingent object of contemporary art, Martha Buskirk, 2003) was written out of this interesting and strange situation. One of the artists responsible for the situation – probably together with Andy Warhol – is, of course, Duchamp. The damages caused by his invention of readymades still remain. But these are certainly not damages in the simplistic common sense argument, asserting that the notion of art is now spoiled since the artistic domain has become the realm of whatever, but rather in a political-institutional sense, properly stressed by a French contemporary philosopher (The Crisis of contemporary art, Yves Michaud, 1997).

It is the death of a utopia, which Michaud labels as the Kantian utopia, an aesthetic utopia of an agreement of individual consciences. The real damage is the will to stick to it or to pretend to stick to it for the sake of finding justifications for our choices in art on an institutional level:

«Whatever are the attempts to counter the disillusion, the utopia is indeed dead (…). Its death corresponds to the end of a certain representation of art and of a certain belief in art. It is already an ancient death. When one thinks of it just a little, it is even strange that old beliefs have as much influence; (...) that some dare to do as if Duchamp’s Fountain could generate the aesthetic agreement of consciences! Who believes in it for a minute and who do they mock?»[17]

Yet, the high institutional-political price to pay for Duchamp’s revolution seems largely worth being paid. It is a price for the benefit of difference, both in art and in our everyday experience of objects, ethical and political, albeit in another level, micro-political since it deals with our connections between life and human social creations. In the art world an important change has certainly occurred. The artist does not claim craft or workmanship as the key for his/her art. Accordingly, a different attitude is requested from the spectator following the change in the artist’s task.

As Buskirk notes throughout her book, Duchamp’s readymades established a new model of artistic authorship (in fact a non-model), a «model» where formal unity is not to play a role anymore. In this manner, without the ghost of formal unity, art works may find their new artistic space in terms of creation of events, an affirmation of difference both in the sense that any and every object is potentially art and in the sense of a re-intensification of our life experience with our environment and its objects.

The spectator has been brought back to the art scene in a political shifting, perhaps a last blow on the «auratic» age of art, but in a sense different from Walter Benjamin («The Work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction», 1936). In any case, the scenario is forever new: at least in the domain of the so-called visual arts where hands and retina are no longer accepted as capable of subordinating artistic experience. The consequence is an opening for new manifestations and different participations: «As the traditional notion of the artist’s hand has been deflected into a profusion of different kinds of manifestations, the works thus produced invite the viewer, whether literally or imaginatively, to occupy the positions vacated by the artist».[18]

As I have stated in the beginning of this paper, the readymade is an event. Duchamp’s actual readymades only remain as part of history – that is the reason why it is bad nonsense to include them in the midst of art works aspiring to a place in the art world. The readymade may remain there, of course, but in a specific room for out of place objects. What really matters is the idea of readymade. Let us state it as clear as possible: the readymades were not a phase in Duchamp’s artistic career. Even less are they a type of art that he invented. They were events causing an invisible transformation by means of the double negation discussed above. They remain as an invitation for new experiments in the same direction, i.e., for gestures or creative acts capable of opening a breach through which art and everyday life find their limits.

After Duchamp, there is no more dialectic of art world and everyday life whereby our common sense can despise the arts for their strangeness and the artist can despise everyday life for being banal or deglamourized. A new space has emerged, a space that one could name virtual in a free use of a concept created by Gilles Deleuze.

Deleuze’s virtual gives room to an alternative to the classical philosophical framework, which conceives existence as reality stemming from possibility. As the French philosopher shows in his difficult Difference and repetition, there remains a quasi-opposition between possible and real that ruins our understanding of difference; and what we understand by «new» is reduced to nothing but an actuality relative to a previous actuality within a continuous line of successive events. It suffices to think of history of art as a sequel of «improvements» and «legacies».

Deleuzean virtuality is never separate from actuality, it never opposes actuality as in our common understanding of the word: as possible or simulated. The virtual is fully real, not lacking anything (nothing like, «only possibilities»). It develops not as in a process of becoming real; but rather, in a process of becoming actual – actual in terms of stable; a state of things possessing qualities. This is the first fundamental difference between possible and virtual. Coming to existence is a continuous and discontinuous process. It is not to be conceived as a sudden leap, although it is always overflowing. There must be a clear cut difference between existent and non-existent. The latter should not be put as reducible to something less real, a mere possibility or nothing at all. It is not (non-existent) while the existent is something, but as an actuality inhabited by virtuality. So is the readymade: it is an objet trouvé, actual, but not «found» as a real everyday life object or as a possible artistic (dream) object as it was the case of the Surrealist objects. It is an actual object made indifferent as such, impossible to find, or «found» solely as virtual.

Second, but not least, still according to Deleuze, if the so-called possible still has always to become real, it remains a simple image of reality, copied from reality, making the new unthinkable as new in its own single form. The possible is just a degraded copy of the so-called real. The virtual, in turn, is reality that remains invisible, neutral. By performing an invisible transformation of a ready-made into a readymade Duchamp points to a virtual where art world and everyday life are unable to recognise themselves, and something new in its own form can emerge. As Deleuze asserts, it is in the process of actualization that one can find a true process of genesis (or creation) since the limits are no longer within the narrow constraints of our concepts. A process of genesis worthy of the name only occurs with the creation of divergent lines corresponding to multiple virtual situations[19].

This second feature of the virtual is essential to understand what I see as some ethical- political consequences of the readymade. They appear in the works of the Brazilian artist «brut» («outsider») Arthur Bispo do Rosario.

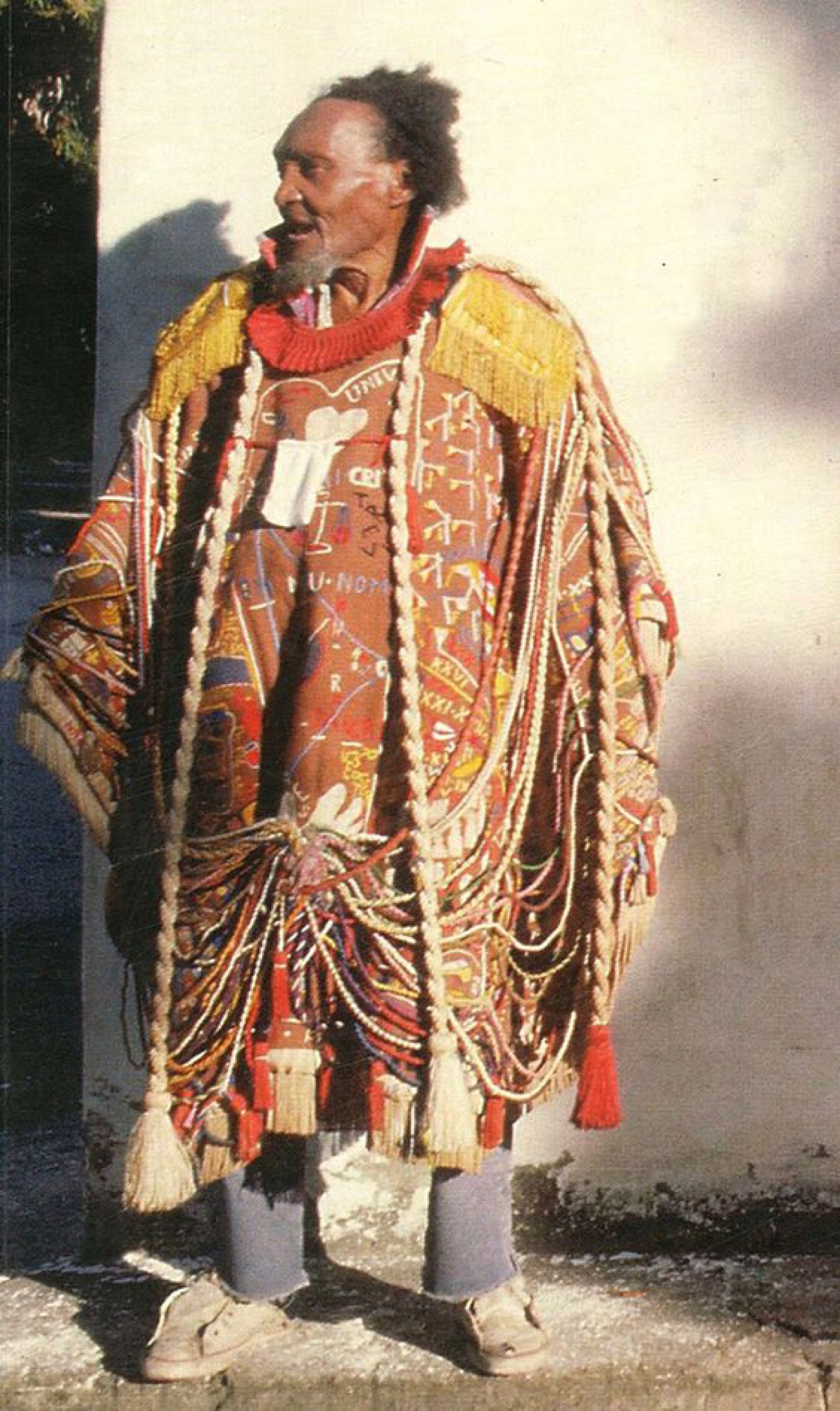

Bispo do Rosario was a Brazilian artist who actually started his works after his internment in an asylum in Rio de Janeiro (Colônia Juliano Moreira), by the end of the 1930’s. Diagnosed as «schizophrenic-paranoid», he lived there for about 50 years. During his long stay in the mental institution, Bispo do Rosario could fashion hundreds of works from different types of materials collected («found») around the asylum and in its courtyard. These works were intended to mark the passing of God on earth reincarnated in him as Jesus Christ. Whenever asked about his choices in terms of craft, Bispo do Rosário said he was told to do that way by voices from beyond. His «mission» would be a reconstruction and/or a «re-presentation» of the world to God in the Judgement Day.

Bispo do Rosario’s best known work is precisely the Manto da Apresentação («Presentation Cape»), which he intended to wear on the Day of Judgement. But most of his themes include household objects and objects related to navigation (Bispo do Rosário was in the Navy during his youth).

One of the most difficult obstacles for the study of Bispo do Rosario’s art lies in the terrible mist that our common sense often lets hover around people (artists, philosophers etc.) in cases of so-called madness. What I mean by that is simple to a certain extent. Our stupidity is prone to dominate all analyses whenever we find something shocking or scandalous about what is to be understood. Mental illness is a clear case of something shocking. Bispo do Rosario experienced hallucinations, wandered the streets of Rio, headed to a church and a monastery; finally he announced he was Jesus, in charge of judging the living and the dead. In short, he was (or went) crazy. After such a very short biography, the next miserable step is to try to explain his art in terms of his illness as if people’s deeds were a projection of their state of mind.

There are, in fact, two tasks to avoid when one decides to approach the difficult relation between art and madness – tasks to bear in mind at any attempt to make sense of the relations between people’s creations and their everyday life. The first is to refuse as positively as possible a comprehension of the works of any artist in terms of his/her mental state or common behaviour. Next, it is also important to avoid separating them, as if they belonged to two different worlds.

Even here, once again, Duchamp’s readymade operation may prove instructive. There are no previous boundaries between art and life; one can never know exactly where the two spheres start and finish in relation to each other, the ready-made and the readymade, for instance. It is always necessary to keep up with the tension, to remain suspended, neutralized, refraining from drawing hasty conclusions.

A second difficulty to approach Bispo do Rosario’s art revolves around the very theme of this paper, namely, the question of the new relation that the readymade kind of work is supposedly able to establish between recognisable everyday objects (ready-mades) and our reality after they become art (readymades). After all, it is clear that the general transformation brought about with Bispo do Rosario’s readymade is quite different from Duchamp’s invisible transformation of indifference. It would be foolish to sustain that Bispo do Rosario’s readymades follow or confirm the Duchampian notion as a new style in the domain of the arts. The «brut» («outsider») aspect of his works is essential to prevent this line of interpretation about what a readymade is or can be. History of art is not allowed here. First, because it is impossible to claim that Duchamp could have had an influence on Bispo do Rosario. He did not know Duchamp. Second, because he never belonged to the art world in general. He could not be less concerned about styles or schools.

Bispo do Rosario’s readymades and the ones created by Duchamp operate in completely different manners. The question is, why then name Bispo do Rosario’s objects readymades? Because both Duchamp and Bispo do Rosario operate the same kind of transformation with their respective different objects. It always consists – in both artists – of «finding» objects of everyday life without ascribing any secondary meaning to them. Duchamp’s readymades and Bispo do Rosario’s «brut readymades» (let us call them this way from now on) are everyday life objects that have been «lost» and cannot be «found», or that can only be «found» as «lost», like Anna, Antonioni’s character in The Adventure.

Everything goes like in Deleuze’s approximation of his virtual object with two famous objects of psychoanalysis: Melanie Klein’s partial object and Jacques Lacan’s «a» object («objet petit a»).[20] Because of the «alienated condition» of Bispo do Rosario it may also be useful to translate the situation in psychoanalytic terms as I did with the Surrealist object above.

According to Deleuze, partiality in Klein is far from meaning, «lacking totality» because the «subtracted part» (the mother’s breast in the case of a child, for instance) is «ripped out» in order to acquire a new nature. A partial object is partial in itself, for itself, creating a new reality: «good breast, bad breast». This subsequent splitting already indicates an achievement of autonomy in the face of a presupposed natural order. As for Lacan, things get a bit more complicated because his celebrated «a» object stands for the object of desire as unattainable, imaginary, in a Surrealist fashion. It is Buñuel’s Conchita once again, «to be found as unattainable». However, if the virtual object is detached from the series of real objects – following Lacan’s logic – it is not in the sense of an expression of desire as lack. It is detached from the series as in Bispo do Rosario’s art, ultimately because they need a new reincorporation, a practical-existential insertion in the world.

To be honest, the question of being or not being attained cannot be a problem because there is no meaning beneath the objects. A readymade is flat. It was the case since Duchamp. It is not the case with Breton. Besides, the real is not impossible for desire, as Lacan used to say; it is to be produced in a practical-existential dimension. So is it for the arts as well.

Yet, Deleuze finds Lacan’s theory of a object useful for it contains the evident secret of the readymade: it always lacks its identity, bicycle wheel with a stool instead of bicycle, bottle-rack without bottles... What identity do they have then if not a virtual one?

Despite their differences, both the objects of Duchamp and Bispo do Rosario can be considered readymades since they can only be «found» as «lost», as missing its own place – everyday life. It is like in Edgar Allan Poe’s Purloined Letter. That is what really matters: Poe’s letter or the ready-made of everyday life as out of place, removed by the characters in the famous short story, by Duchamp to enter the museum, or by Bispo do Rosario to be re-presented in the Judgement Day to God. But following an important argument put forward by Jacques Derrida («The Purveyor of Truth», 1975) after Lacan, it is not a problem of lack of meaning. It may be much simpler. The meaning is not lacking. It is lack[21]. It is not a case of playing with words without being, rather, a confirmation of the second aspect of Deleuze’s virtual. A space has been excavated in between «lost» and «found», so that the new can emerge, a re-actualization of the art world and everyday life. The meaning is the lack of definitive meanings without investing what is supposed to mean.

The ready-made objects of everyday life have been taken out from their actual world to become virtual objects, but they are not objects of desire without being, primarily, practical objects of everyday life. In the case of Duchamp, they are not objects of desire at all; hence their indifference. The case remains for Bispo do Rosario.

In any case, there are at least two very important and decisive differences between Duchamp’s readymades and Bispo do Rosario’s. Firstly, Duchamp makes the ready-mades get «lost» in the museum, creating the out of place situation while Bispo do Rosario simply ascertains that the objects are «lost» in this world because the entire earth is going to be razed in fire[22]. Consequently – and this is the second fundamental difference –, Bispo do Rosario’s ready-made objects are not to be «found» exactly as «lost», merely out of place as it was the case in Duchamp’s art. They undergo a process of genesis with the creation of divergent lines inasmuch as they must be assembled and prepared.

Bispo do Rosario’s readymades are indeed «found» because they are slightly remade, although not in the sense of Andy Warhol and other pop artists. It is a remaking in the sense of a gathering and a classification because the objects are going to be presented in the Judgment Day. As said above, that would be his mission, and it is repeated at least twice, in an interview included in a publication, and again in a very important film about the artist (Prisoner of the passage, Hugo Denizart, 1982):

«INTERVIEWER – Can you please tell me about that mission of yours?

BISPO DO ROSARIO – My mission is to succeed the next day to represent the existence of the earth that is there.

(...)

DENIZART – Are these representations of miniatures?

BISPO DO ROSARIO – It is the material existing on earth for the use of man.

DENIZART – Is it a representation of everything on earth?

BISPO DO ROSARIO – Yes, they are the work of what exists.»[23]

It seems that the negation is no longer double in the case of Bispo do Rosario. The transformation ceases to be invisible too. Bispo says he was told to «represent» the existence of things on earth, which implies that the gesture cannot be negative anymore. Everyday objects are not collected on the basis of their indifference as in the case of Duchamp. But it is important to remain attentive here. They are not collected out of their beauty or of any special value either. They remain everyday objects. In short, the gesture is not negative. After all, Bispo do Rosario has a mission. It is the gesture of a mission. Nevertheless, his objects are themselves negative in the same sense of the anonymity and neutrality stressed by Octavio Paz.

However, even anonymity has a slightly different sense in Bispo do Rosario’s art, as the recent paper quoted above, published by two psychoanalysts, has helped to make clear («Bispo do Rosario and the representation of the materials on earth», Corpas & Vieira, 2012). As the authors conclude, Bispo do Rosario’s work comes out of the delirious dynamic of his mind, but this is what allows him to establish a link with the cultural environment. It is what gives him that plus of social bond partially broken after his psychotic outbreak[24].

Bispo do Rosario’s brut readymades keep Duchamp’s neutral feature because they do not belong to any art world or to everyday life anymore. Thus, on the one hand, they exist in a liminal zone, neither art nor life as self-contained domains. On the other hand, they are also anonymous, completing a negation, but only to a certain extent because, after all, there is a work of assembling and preparing – the task of «re-presentation». Anonymity is therefore relative; it is valid for the objects, but still, these have to be presented again (re-presented), which requires someone suitable for the task. This suitable position does not reinstate a negative gesture though. Bispo do Rosario’s readymades constitute a single negation. Taste or institutions do not have any importance whatsoever. There is no negation on this level.

It is precisely the second merit of Corpas and Vieira’s article. As the authors succeed to demonstrate, the widespread idea about Bispo do Rosario’s work being simply reconstruction of the world misses the very core of his enterprise, which is to show, introduce or present, again, God’s creation. His readymades must therefore be thought within a process of genesis or radical re-creation. They are a world coming into being in a concrete manner, not as a mere metaphor. The work of any artist entails the creation of a world, which allows us to label everyday life atmospheres accordingly, Kafkaesque traps in the domain of our institutions, Fellinean types that emulate reality (like the famous Paparazzo)... And so forth. With Bispo do Rosario this process becomes as clear as ever. It is the second aspect of Deleuze’s virtual mentioned above: the limits of art and life dissolve, their lines converge to attain divergence, i.e., household objects or the presentation cape are and are not just household objects and a cape to wear. As a different complement to Duchamp, the readymades are now to be used, but with a new purpose. They are created or taken from everyday life to be re-presented, re-invested, re-intensified in a better life after the Judgement Day.

Bispo do Rosario’s readymades excavate the same nowhere zone of Duchamp’s readymades, but already connected with the outside as potential space. In short, the two outsides, proper to art and life, are immediately connected with a practical-existential dimension, a new life (for Bispo do Rosario, an afterlife), a life new in its own form, as in Deleuze’s understanding of what newness is supposed to be.

We have finally reached a new paradox amongst many. I still remember the cold reactions of people in one of the first exhibits of Bispo do Rosario’s works in Rio de Janeiro’s MAM (Museum of Modern Art): «this cannot be art, after all these are just objects with no intention to be considered art». A twofold accusation: not only the classical one, usually raised against Duchamp or Warhol, of «mere objects», but the intellectual and historicist one, which demands a place and an intention in order to justify what art can be. Once again, it is clear that the resolution formula «an ordinary object elevated to the dignity of a work of art by the mere choice of an artist» cannot apply to readymades. It is rather a lowering in Manoel de Barros’s fashion, capable to challenge aestheticism, a lowering in the name of a practical-existential «elevation» of tiny things in life. It is life elevated as a potential space for a new world as one expects the Judgment Day. No doubt, «judgment day» is bound to be metaphorical here. It stands for all turning points a life can bear.

Nonetheless, Corpas and Vieira’s article on Bispo do Rosario loses focus as their analysis progresses. It is often the problem with psychoanalysis. After stressing the advantages, or even the necessity, to take Bispo do Rosario’s words about «representing the materials on earth» literally; after having shown that representation in his case does not bear any mimetic meaning... the authors seem to stumble. First by arguing that the term representation indicates, «Not addressed to God alone, but to society», when the most important is the idea of presentation. Secondly, which is much more serious and spoils their enterprise, by interpreting Bispo do Rosario’s art in terms of a compromise, a last resort exit in the face of madness.

It is evident that psychoanalysis has a lot to say when it comes to Bispo do Rosario’s art. After all, we are dealing with an extreme case of unconscious activity of creation. But why such a reactive claim that «for being incapable to establish a stable delirium by the sole means of imaginary re-creation of his self, Bispo do Rosario had to appeal to the production of objects…»?[25]

Such a hypothesis and interpretation is unacceptable. It even goes against the whole intention of the article, which claims on the same page not to be interested in treating delirium as pathology.[26] But the temptation is always too strong every time psychoanalysis stumbles and assumes the strange role of a scientific attempt to regulate our inner conflicts.

Fortunately, it does not have to be this way. We find in the works of another psychoanalyst (Donald Winnicott) a way out from this psychoanalytic true fever of drives, discharges, defences, adjustments etc. With Winnicott, the background map of our connections matters first and above all. All objects are there. All impulses deploy on this basis of a plurality of objects. It is on this ground that one should set feet. Consequently, Winnicott has been deemed to belong to a new trend in psychoanalysis: the object relations fashion.

Of course, it goes much beyond my ambitions to provide an accurate and minimal account of such a difficult matter. It suffices for me to clarify one thing before closing this text: the object relations terminology still sounds vague, besides not capable to reveal the extent of Winnicott’s originality (I would prefer to talk about environmental-transitional-developmental trend). At any rate, it is important to let the contrast hereby established as clear as possible with the aid of one of the first and most consistent attempts to make sense of the so-called object relations trend.

Thus, a 1983 book by Greenberg and Mitchell (Object relations in psychoanalytic theory) blames Winnicott for a systematic misreading of Freud and concludes about the former: «As his work developed (...) it became apparent that Winnicott was proposing not an extension, but an alternative to Freud’s approach. He is offering a framework for understanding psychopathology which, firmly rooted in the relational model, is at odds with classical formulations based on drive and defence».[27]

The contrast makes perfectly understandable Corpas and Vieira’s derogatory interpretation of Bispo do Rosario’s «representation of the materials on earth» as a last resort in face of his disability to recreate oneself beyond an imaginary structure. After all, the authors inscribe their efforts in Lacan’s approach to psychosis, which ultimately gravitates around the same drive and defence orbit; a world where a fundamental Narcissism reigns and it is our relations to others that need explanation, not our development within an environment.

It does not matter. With Winnicott, Bispo do Rosario’s objects of lunacy can finally become, not a last resort or a dramatic appeal, but an affirmation of difference in the second sense sustained in the beginning of my paper: a sense of a re-intensification of our life experience in an environment, with its objects and their common use. They can appear as virtual objects turned into transitional ones.

«I have introduced the terms ‘transitional object’ and ‘transitional phenomena’ for designation of the intermediate area of experience (...) It is generally acknowledged that a statement of human nature is inadequate when given in terms of interpersonal relationships, even when the imaginative elaboration of function, the whole of fantasy both conscious and unconscious, including the repressed unconscious, is allowed for. There is another way of describing persons that comes out of the researches of the past two decades, that suggests that of every individual who has reached to the stage of being a unit (...), it can be said that there is an inner reality to that individual, an inner world which can be rich or poor and can be at peace or in a state of war.

(…)

My claim is that if there is need for this double statement, there is need for a triple one; there is the third part of the life of a human being, a part that we cannot ignore, an intermediate area of experiencing, to which inner reality and external life both contribute. It is an area which is not challenged, because no claim is made on its behalf except that it shall exist as a resting place for the individual engaged in the perpetual human task of keeping inner and outer reality separate yet inter-related.»[28]

A transitional object belongs to a third intermediate area of experience. It is virtuality establishing connections. One may ask: but how exactly Deleuze’s virtual objects become transitional in the Winnicottian sense? My sketchy hypothesis is that this new aspect of the readymades is clinical, i.e., it is revealed as one gets closer to artists and viewers in their lives. It shows off, for instance, in the case of Bispo Rosario’s art, as an essential aspect allowing him to change and develop his self-perception regardless of any inner pseudo-necessity to contain his delirious imaginary production. On the contrary, Bispo do Rosario is not unable to re-create himself by means of anything and so remakes objects; he can only re-create a self out of those very objects, in a process of genesis that includes the world and his own self in the world together and separate at the same time.

The intermediate area of experience is neither intra-psychic nor merely shared reality; it is a liminal zone or border, a potential space in which infants or patients like Bispo do Rosario can create what is to be found. What an infant «creates» is his/her transitional objects, Teddy bear or blanket like in Charles Schulz’s character Linus. Following the same logic, a readymade is an object found to be created, a transitional object as well, but carrying out a different correlative transition in which the practical-existential dimension of things around us is rescued from mere habit and/or conservative formalism.

With Bispo do Rosario, readymades become what they are: third parties included, art and non-art, life as it is and after-life as it is not yet (and we do not know if it will ever be). They operate a transition in the development of art and life, not only for the schizophrenic Bispo do Rosario, but for a fundamental schizoid dynamic that haunts us all. They reveal this third part inherent to all relationships, which points to the horizon, to cosmos, to the environment according to Winnicott. They are objects pulled from their context, turned into a formless matter that can only gain form and make sense in a practical-existential dimension. For Bispo do Rosario it is the practical-existential dimension of a sacred task. It remains for each of us to know how these objects can be put together.

As Winnicott explains, the third area of experience ultimately subsists as a resting place for the individual engaged in the task of keeping inner and outer reality separate yet inter-related. That is the challenge. Duchamp’s readymades kept separate and inter-related the world of aesthetics (institutions and trained taste) and everyday life. Bispo do Rosario’s readymades kept separate and inter-related, on the one hand, his mental state and the hostile environment that threatens all schizophrenics today and ever; and on the other, this world and its re-presentation for the Judgement Day – call it art or not.

Works Cited and Consulted:

Artaud, Antonin. Le théâtre et son double (1938). Paris: Gallimard Poche, 1985.

---, Collected works. Volume Four. Translated by Victor Corti. London: Paris & Boyars, 1974.

Atkins, Robert. Art Speak: A Guide to Contemporary Ideas, Movements, and Buzzworks, 1945 to the present. New York: Abbeville Press Publishers, 1990.

Benjamin, Walter. «The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction» (1936), in Illuminations. Edited with an Introduction by Hannah Arendt. Translated by Harry Zohn. New York: Schocken Books, 1977.

Barros, Manoel de. Tratado geral das grandezas do ínfimo. Rio de Janeiro: Record, 2001.

Bourdieu, Pierre. The Rules of Art. Genesis and Structure of the Literary Field (1992). Translated by Susan Emanuel, Stanford California: Stanford University Press, 1996. https://bildfilosofi.files.wordpress.com/2009/12/therulesofart.pdf

Breton, André & Éluard, Paul. Dictionnaire abrégé du surréalisme (1938). Paris: José Corti, 1991.

---. «Équation de l’objet trouvé» (1937). http://www.arcane-17.com/medias/files/e-quation-de-l-objet-trouve-andre-breton-.pdf

Buskirk, Martha. The Contingent object of Contemporary Art. Cambridge, Mass. and London: The MIT Press, 2003.

Corpas, F. S. & Vieira, M. A. «Bispo do Rosario e a representação dos materiais existentes na Terra». Tempo Psicanalítico, v. 44, n. 2, Rio de Janeiro, 2012. http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0101-48382012000200010

Deleuze, Gilles. Cinéma 2: L’Image-temps. Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit, 1986.

---. Différence et répétition. Paris: P.U.F, 1968.

---. Logique du sens. Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit, 1969.

--- & Guattari, Félix. Mille Plateaux. Capitalisme et schizophrénie II. Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit, 1980.

Derrida, Jacques. «The Purveyor of Truth» (1975). http://users.clas.ufl.edu/burt/Burt%20Glossator/purveyor_of_truth.pdf

Domenech Oneto, Paulo. «Geopoética de Manoel de Barros em dois movimentos e um adagietto» in Souza, Elton. Poesia pode ser que seja fazer outro mundo – uma homenagem a Manoel de Barros. Rio de Janeiro: Sete Letras, book in press, 2017.

Duchamp, Marcel. Du Champ du signe. Écrits (1958). Réuni et présenté par M. Sanouillet, nouvelle édition revue et augmentée avec la collaboration de E. Peterson, Paris: Flammarion, 1994.

---. In Cabanne, Pierre. Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp. London: Thames and Hudson, 1971.

---. In Seitz, William Chapin & Shattuck, Roger. The Art of Assemblage: A Symposium, October 19, 1961. New York, N.Y.: Museum of Modern Art, 1967.

---. In Sweeney, James Johnson (ed.). The Museum of Modern Art Bulletin (New York), vol. 13, no. 4/5, 1946.

Foster, Hal. «The Crux of minimalism». https://pt.scribd.com/doc/109323090/Hal-Foster-The-Crux-Minimalism

Greenberg, Jay & Mitchell, Stephen. Object relations in psychoanalytic theory. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1983.

Michaud, Yves, La Crise de l'Art contemporain. Utopie, démocratie et comédie. Paris: P.U.F., 1997.

Passeron, René. Encyclopédie du Surréalisme. Paris: Éditions Aimery Somogy, 1975.

Paz, Octavio. «The Ready-made» (1970) in Masbeck, Joseph (ed.). Marcel Duchamp in perspective. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, 1975.

Winnicott, D.W. «Transition Objects and Transitional Phenomena» in Through Paediatrics to Psycho-analysis (1958). London: Hogarth Press: 1975.

Footnotes

- ^ Passeron, 1975: 9.

- ^ He talks of «visual indifference» (Duchamp, 1971:4 8).

- ^ Cf. Atkins, 1990: 107.

- ^ Cf. Duchamp, 1946.

- ^ Cf. Domenech Oneto, 2017.

- ^ Cf. Duchamp, 1958: 191 and 173.

- ^ Cf. Artaud, 1974: 58-59.

- ^ Paz, 1970: 84.

- ^ Cf. Deleuze, 1985, chapter I.

- ^ Paz, 1970: 87.

- ^ Idem, ibidem.

- ^ Idem, 86.

- ^ Idem, 86-87.

- ^ Foster, 1987: 56.

- ^ Cf. Deleuze & Guattari, 1980.

- ^ Paz, 1970: 87-88.

- ^ Michaud, 1997: 250.

- ^ Buskirk, 2003: 243.

- ^ Deleuze, 1968: 273-274.

- ^ Cf. Deleuze, 1968, chapter II.

- ^ Cf. Derrida, 1975.

- ^ Cf. Apud Corpas & Vieira, 2012: 415.

- ^ Idem, 407.

- ^ Idem, 419.

- ^ Idem, 409.

- ^ Idem, ibidem.

- ^ Greenberg & Mitchell, 1983: 209.

- ^ Winnicott, 1958: 230.