Like a hatch in the closet of a magician

Mário Moura & Susana GaudêncioSo we are asked to speak about the gap. We understand it as a missing space. A flaw, a breach. But since we are committed to the arts we also realize that a gap may be useful, it opens up pathways, separates material. But more importantly, a gap may have its own space, a space which is not necessarily worse than the space that it is separating.

–

Think about that trick of the cup between two faces. Or, more precisely, think of an Escher mosaic, where background and figure rapidly change function: the goose merges into the landscape that merges into the goose. That’s not really a gap, you’ll think, but only an optical illusion.

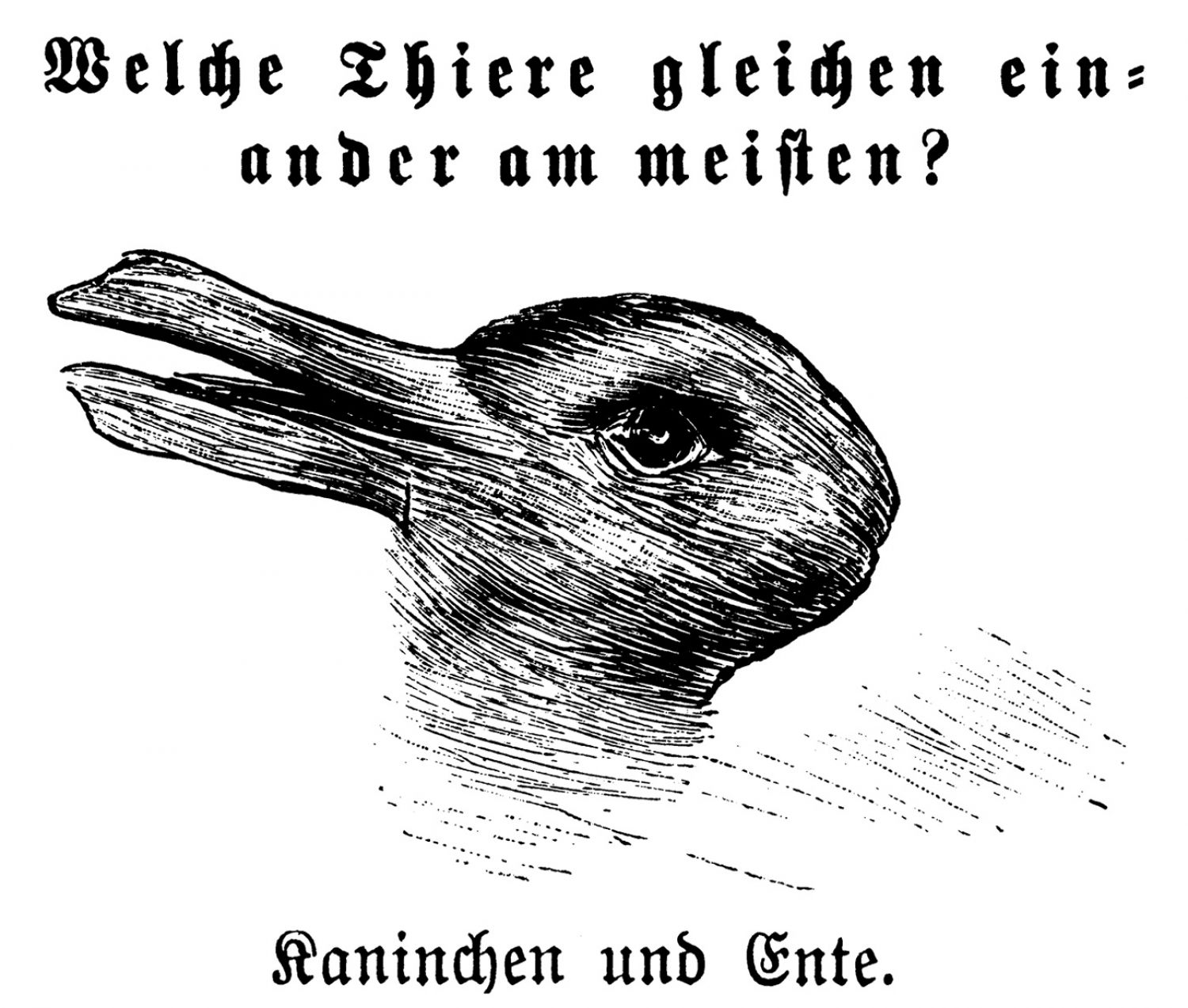

The question becomes even more pertinent with Wittgenstein’s famous Duck-Rabbit, who always seems to be oscillating between two states, with no definite transition. There seems to be no break, no midway moment between duck and rabbit. These images that accumulate different – even opposite – readings are called «multistable». Following WJT Mitchell:

«Multistable images are also a staple feature in anthropological studies of so-called 'primitive art'. Masks, shields, architectural ornaments, and ritual objects often display visual paradoxes conjoining human and animal forms, profiles and frontal views, or faces and genitals. The 'fort-da' or 'peek-a-boo' effect of these images is sometimes associated with forms of 'savage thought', rites of passage, and 'liminal' or threshold experiences in which time and space, figure and ground, subject and object play an endless game of 'see-saw'.»[1]

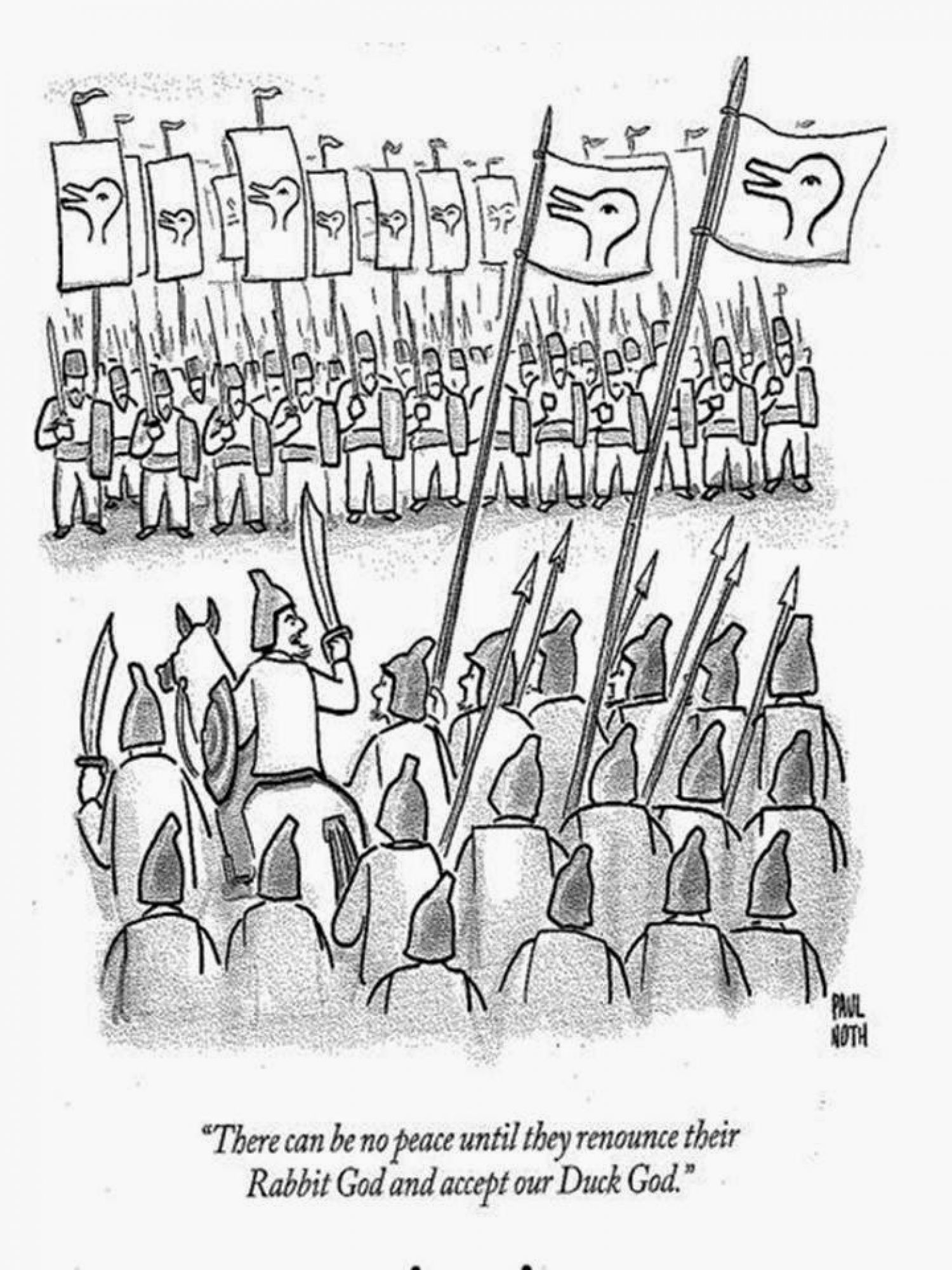

There is a cartoon by Paul Noth where two armies face each other in a war. On one side are those who worship the «Rabbit God», on the other those who worship the «Duck God». Their flags are, as expected, equal. The only thing separating them is an opposed and fixed interpretation of the puzzle. It is supposed that each side is led by its own culture, habits, laws, traditions, leader, to see a duck and never a rabbit and vice versa. Here the gap is political, and determines the perception of each of the armies.

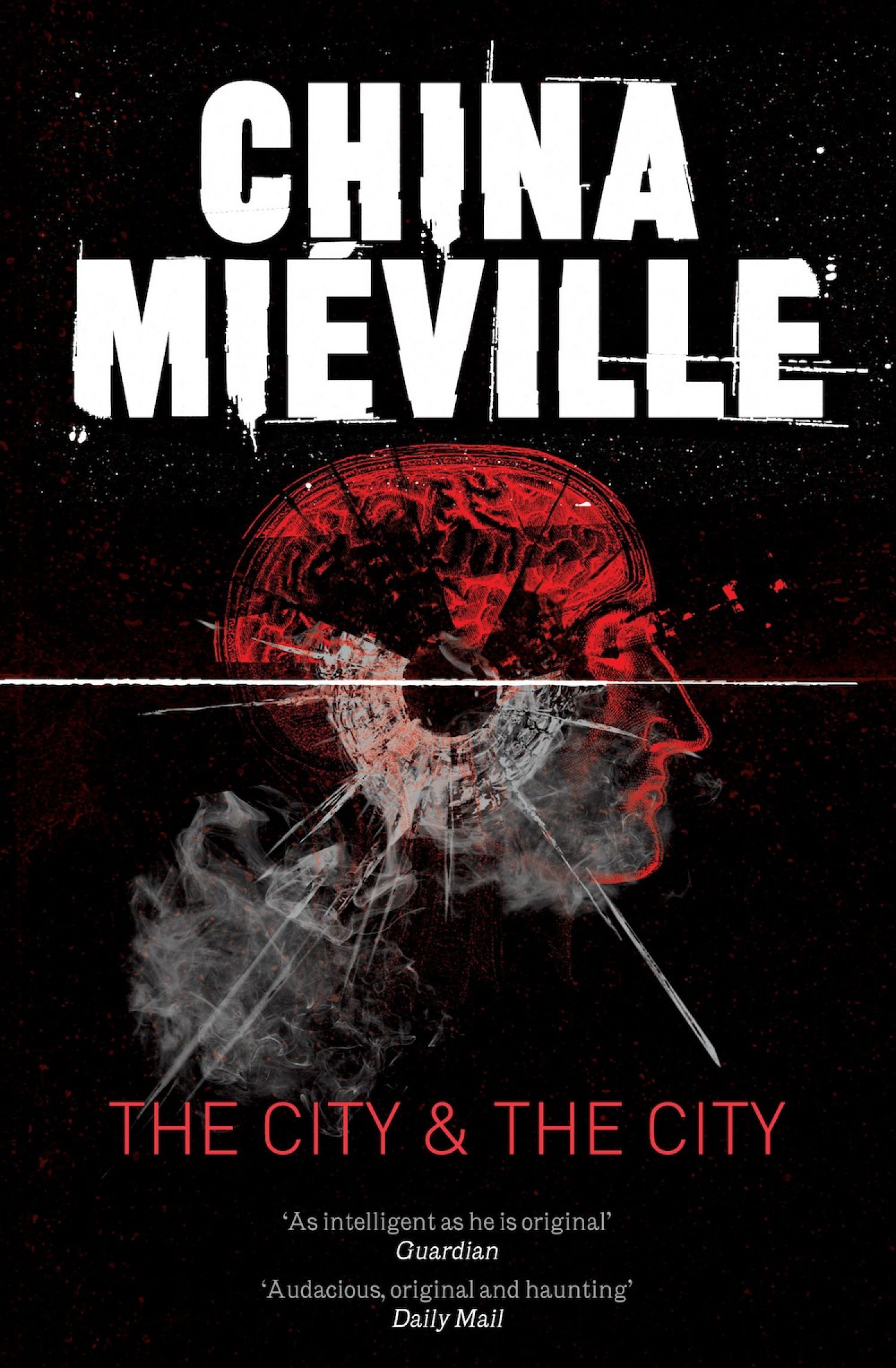

In one of China Mieville’s books, The City & The City, the antes are raised. It describes two independent countries that coincide in the same city, and that have different languages, architecture, customs, laws and even body language that prohibits their citizens from seeing each other. The police force that ensures the maintenance of this order is called Breach. They move between the two cities using a dress code, speech and body language that lie halfway between each community, being therefore invisible. One can imagine that the emblem of this police force could be a «multistable» image, perhaps a heraldic Rabbit-Duck.

It’s an extreme case but it makes us think about how much of the exclusion and how much of the political begins at the level of the sensible. That is the thesis of Jacques Rancière, what he calls the Distribution of the Sensible:

«(…) I call the distribution of the sensible the system of self-evident facts of sense perception that simultaneously discloses the existence of something in common and the delimitations that define the respective parts and positions within it. A distribution of the sensible therefore establishes at one and the same time something common that is shared and exclusive parts. This apportionment of parts and positions is based on a distribution of spaces, times, and forms of activity that determines the very manner in which something in common lends itself to participation and in what way various individuals have a part in this distribution.»[2]

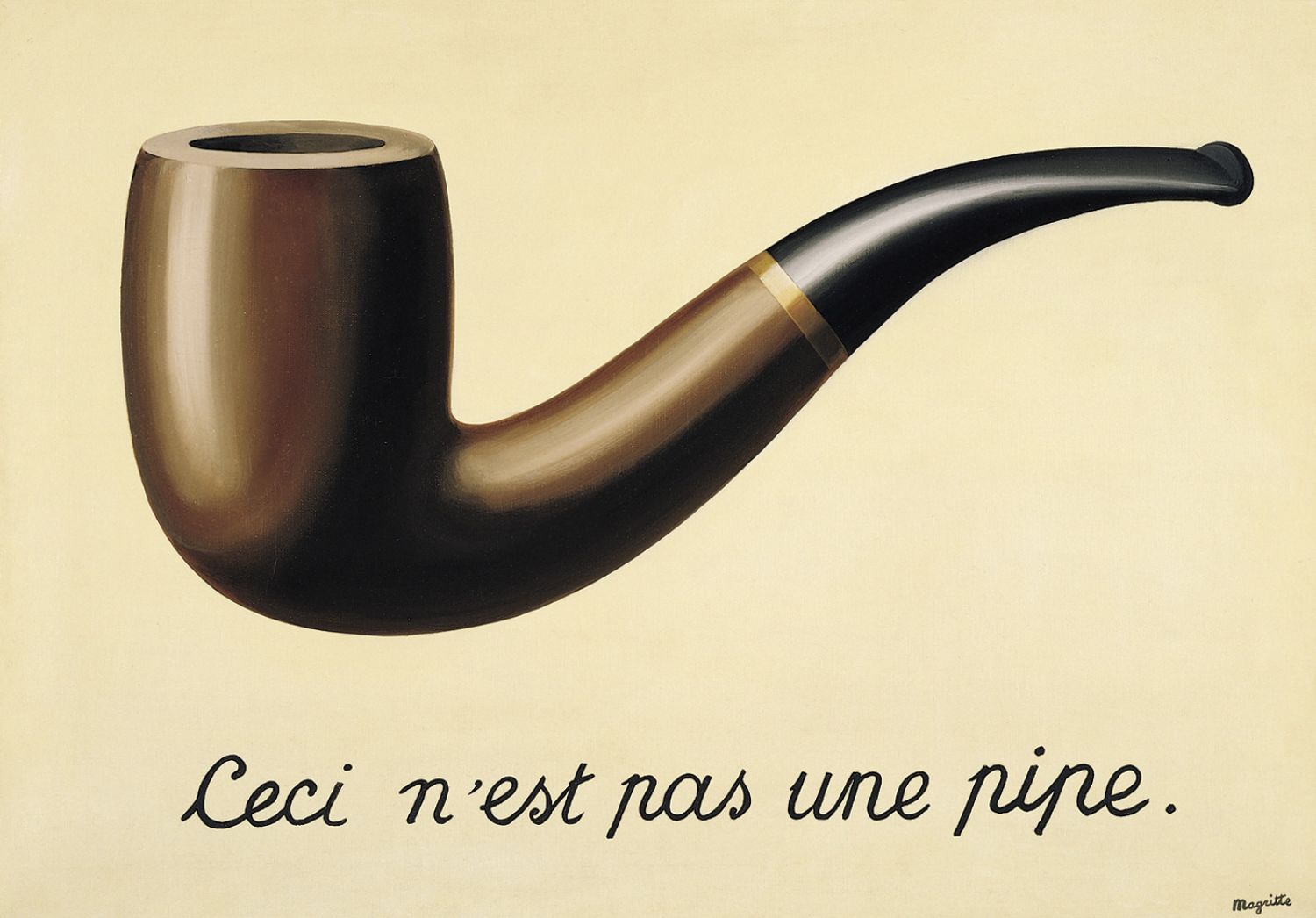

The title of the famous Magritte picture with the image of the pipe whose caption ensures us that it is not a pipe is The Treachery of Images. «Treachery» may seem an excessive term – it is common for captions and images to have an ambiguous relationship. In the film Letter from Siberia (1957), by Chris Marker, the same scene is told in three distinct ways, pro-Soviet, anti-communist and «neutral» giving no conclusion other than that it is natural for images to have different interpretations. The Magritte painting simulates the drawings in textbooks, underlining an official pedagogy, one where we learn following a certain order, a certain discipline which also passes through an expected relationship between words and images. And it is in that official relationship between word and image that betrayal occurs. As Michel Foucault said about that same painting:

«On the page of an illustrated book, we seldom pay attention to the small space running above the words and below the drawings, forever serving them as a common frontier. It is there, on these few millimeters of white, the calm sand of the page, that are established all the relations of designation, nomination, description, classification.»[3]

A Gallery Portrait is a novel by George Perec, about a painting collection. It works as a catalog, specifying several details – provenance, author, title, value of the works in that collection –, but more precisely, it is about a particular painting, the one which names the text, A Gallery Portrait, and that raises a particular fascination in the public. This painting is a portrait of a collector who’s seated, admiring several paintings from his collection. Thanks to an intelligent staging (the mirrors shown in the painting), the scene is repeated infinitely, increasingly small. In each of the successive reflections, slight changes are introduced relative to its initial representation.

Georges Perec presents us with a decoy, or rather a series of deceptions related to a mediation on originality and replication. Now this artifice is camouflaged by the way the author tells his story through a realistic and unpretentious style, using fictional elements along with true events, strongly relating the word – or verb-speech – and image, in a kind of mise en abyme that gives us a constant sense of vertigo between truth and lie. And it is in this range or gap between fiction and reality that the art object is produced. The gap is the decoy, a meta-textual creation that becomes part of the work itself.

The visual experience of the mise en abyme is like standing between two mirrors and seeing your own image repeated infinitely. This mirror effect can reach the point of instability, and can, in this sense, be understood as part of a recursive process. As a literary technique it consists in the inclusion of one or several stories inside a main narrative. The sequence of the main story is interrupted by the introduction of a different situation, as in A Thousand and One Nights (IX century) or in Decameron (1348-1353) by Bocaccio. At a time when narratives and traditions were transmitted orally and books were recited, the story within a story format presented an advantage. The reciters could select the reports that they preferred, ignore the ones they liked least, and add new stories. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818), is also a good example of multiple stories: the character Robert Walton writes in a letter to his sister a story that Victor Frankenstein told him; and Frankenstein’s report contains the story of the creature / monster, which in turn contains a brief history of his family. In literary criticism, this is paradigmatic of the inter-textual nature of language, in the sense that language never reaches the footing of reality because it refers to another kind of language, which refers to another language, and so on.

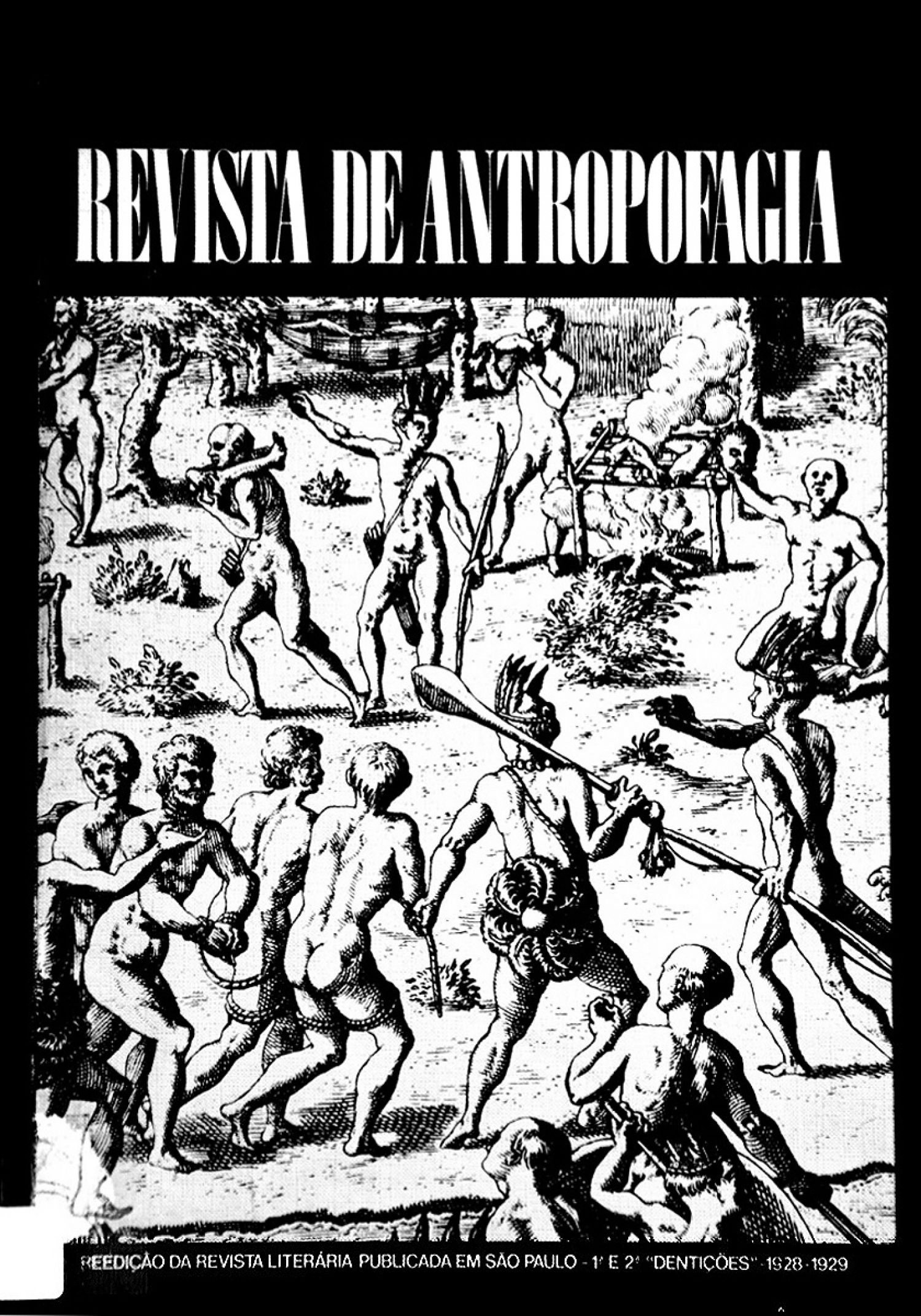

The Manifesto Antropofágico (Cannibalist Manifesto), written in 1928, was published in the Journal of Antropofagia that Oswald de Andrade – one of the main protagonists of Brazilian Modernism, – founded with Raul Bopp, and Antonio de Alcântara Machado, defining with it the movement of Antropofagia: «The magazine of antropofagia (cannibalism) has no positioning or thought of any kind: it just has stomach»[4] But the stomach is an apparently hollow body, a receptacle which can be reached through the slit that is the mouth.

Cannibalism means the quality or habit of a person who eats human flesh; it designates the ritual practices of some indigenous communities in Brazil that, for example, consisted in the meat intake of enemies imprisoned in combat, in order to take possession of their strength and energy. The modernist manifesto was part of a creative strategy that sought to question the cultural, political and economic bases imposed by the European colonizers in the Brazilian artistic and intellectual context. Metaphorically, the intake presented by the Cannibalist Manifesto, is the process through which Brazilian culture tends to critically assimilate the influences and loans arising from these dominant cultures. Brazilian culture comes to define itself not by stable compositional elements, but by an aggressive attitude, the attitude of creative swallowing, which is a concept that stems from the magical and ritualistic meaning of cannibalism.

The idea of a latent cannibal character in this cultural movement had as reference the readings of sixteenth century writers such as Hans Staden (1525-1579), a German who was a prisoner of the Tupinambás Indians for nearly nine months, expecting, during that time, to be devoured. Some of the Journal of Antropofagia’s illustrations were drawn from his work Duas Viagens ao Brasil (True Story and Description of a Country of Wild, Naked, Grim, Man-eating People in the New World, America) (1557) and show details of the cannibalistic ritual. How to interpret these scenes of cannibalism, from the days of colonization, which occupy quietly the background landscape? Indians cutting up and cooking white missionary men, these special envoys sent to cover up the surfaces of a so called primitive culture with pure religion, Baroque and tiles, inflicting on others the horrors of a rough indoctrination to which they themselves were subject to. The Catholic Church had to invent the savagery of indigenous peoples in order to justify their massive extermination. However, few civilized Christians remember the wedding at Cana and have the notion that, in the Eucharist, they also play a cannibalistic act – St. John says in his gospel, «Those who eat my flesh and drink my blood live united in me and I in them».[5]

In Portuguese the word Baroque has the sense of an imperfect pearl, or false jewel. In Europe, the Baroque style, in the arts, music and literature was a contemporary of the horror caused by the Inquisition. The tension between opposite elements rouses in the Baroque artist a deep anguish because he lives in a gap, or split, between the inside and the outside, like a fold that replicates on both sides. Severo Sarduy (1937-1993) Cuban poet, writer and critic, in his text on the Baroque, talks about a «Chamber of Echoes, (...) as a space where we hear resonances without ever submitting to a sequence or any notion of causality, where an echo often precedes a voice.»[6] He also mentions the reversal of a known historical chronicle into a narrative without dates, highlighting the importance both of what is included as well as what is hidden, obliterated or forgotten, in the construction of a narrative.

The empty space of that «Chamber of Echoes» represents the absence of the evidence that usually confirms a historical or narrative fact, thus opening up to other possibilities to imagine and create. We can compare it with the great unconformities rock layers that represent a void in the geological time marker and in the information about the changes that originated it. These geological peculiarities are frequent and represent a hiatus in Earth's history, like the missing pages of a book.

The Baroque consisted of a mixture of various trends, Portuguese, French, Italian and Spanish, and its focus was of an art dedicated to spiritual and decorative issues. By suppressing all the transitions between light / dark, it was like we were suddenly falling into an abyss or chasm, abruptly juxtaposing opposites. Art goes beyond mere mimesis, working as the transmission vehicle of an inner feeling.

Caravaggio's painting (1571-1610), a major artist of that time, represents one of Baroque’s central themes: the questioning of religious thought and therefore the questioning of the existence, or absence, of God. In The Incredulity of Saint Thomas (1601-1602), Thomas needs to "see to believe" like the Baroque man did, he who no longer accepted uncritically Catholic standards. Metaphorically, Thomas’ doubt is the doubt of the Renaissance man before the political theological thought of the time: in the Baroque there is tension in the attempt to unite opposing views – the anthropocentric, inherited from the Renaissance, and the God-centered, recovered by the Counter-Reformation, as is evident in the disbelief of Saint Thomas. Caravaggio’s work mirrors the dissonant harmony of Baroque aesthetics, by reflecting these contradictory aspects such as light and shadow, the sacred and the profane, the interior and the exterior. The moment depicted is transcendent: Jesus, raised, looms among his apostles. The finger that prods the wound into an open slit signals human disbelief, the desire to make sure before accepting a miracle that seems impossible.

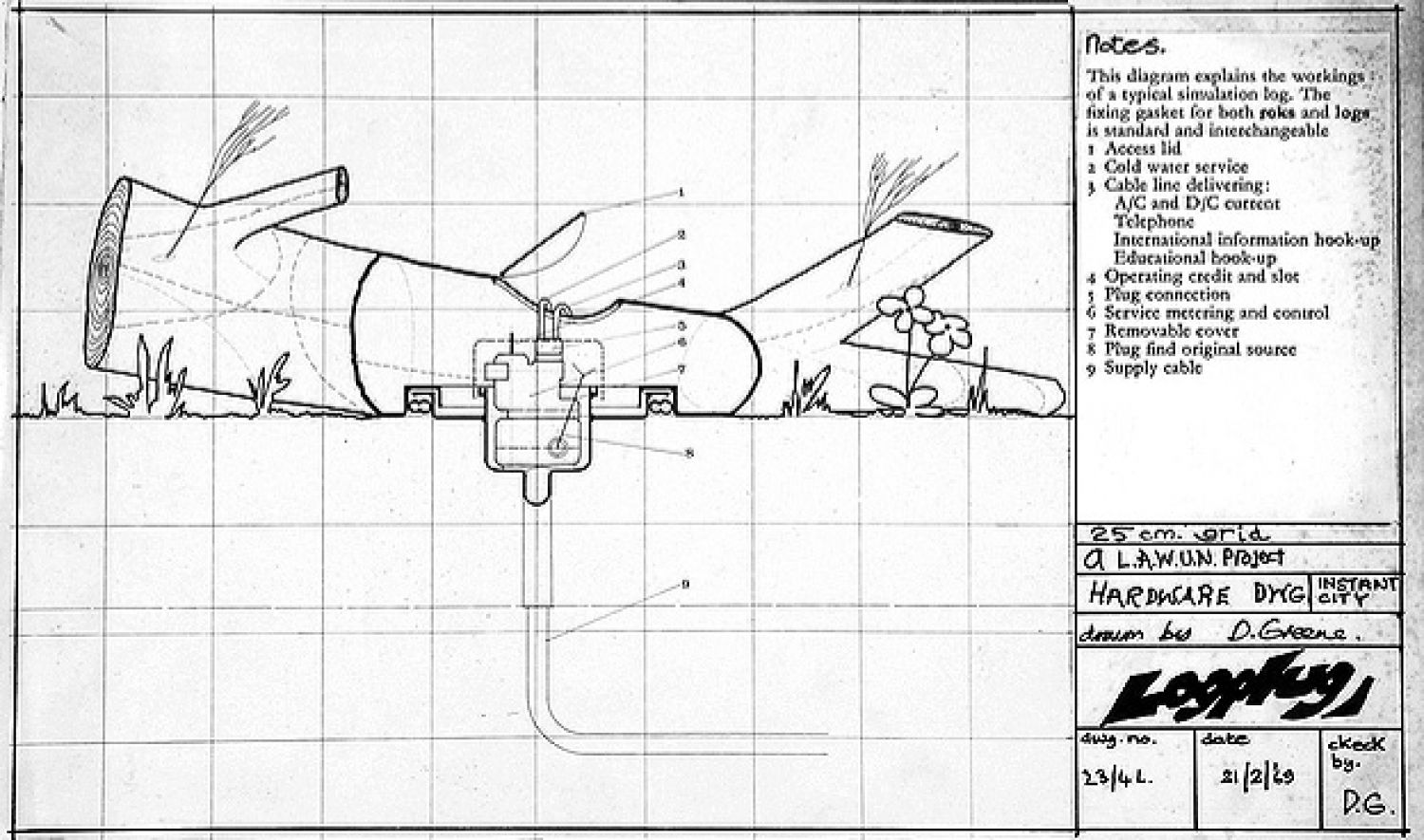

David Greene is a British architect and one of the founders of the magazine and experimental architecture group Archigram (1961). Greene’s project L.A.W.u.N. (1969) is part of his long research on the idea of invisibility in architecture and the possibility of creating a «full service natural landscape»[7]. The natural world keeps its appearance, but is served by invisible networks, LAWuN (Locally Available World unseen Networks). This vision of a fully integrated technology environment seems to herald the current invisible architecture of information known as WI-FI. So the Rockplugs and Logplugs would be replicas of rocks or logs, subtly installed everywhere in the natural world functioning as L.A.W.u.N. containers for a nomadic life. The traveler could locate them via a mobile panel or a home device, and once connected he could select the desired services, paying them through an attached credit card system. The idea of transparency and invisibility is one of the characteristics of the modern world. Electromagnetic waves had already begun to be transmitted through the air and the advance in radio technology, telephone and television meant that faraway places could be connected virtually establishing therefore the possibility of a world transformed by instant communication, invisible and wireless. The fact that advanced capitalism makes increasingly abstract the concept of exchange and value, allowed for the invisible to organize the world in a much more fundamental way than urbanism or architecture. Today, space is manufactured through the influence of those invisible forces – it seems to be missing or hiding. The idea of nothing, of the disappearance of substance, influences all our experience, where «seeing is believing» no longer proves anything.

Footnotes

- ^ MITCHELL, WJT. (1994). Picture Theory. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- ^ RANCIÈRE, Jacques. (2004). The Politics of Aesthetics: The Distribution of the Sensible. Londres: Continuum.

- ^ FOUCAULT, Michel. (2007). Isto Não é um Cachimbo. São Paulo: Paz e Terra.

- ^ BOPP, Raul and MACHADO, António A. (1928). «Nota Insistente». Revista de Antropofagia. N.º 1 (Maio), p.8.

- ^ VVAA, «João 6:56» A Biblia—Novo Testamento. Abibliaparatodos.pt - Biblia OnLine. Available at: http://www.abibliaparatodos.pt/Biblia/BibliaCapitulo.aspx. Accessed in 23/08/2015.

- ^ SARDUY, Severo. (1975). Barroco. Paris: Editions du Seuil.

- ^ GREENE, David e HARDUNGHAM. (2008). L.A.W.U.N* Project #19: The Disreputable Projects of David Greene. Londres: AA Publications.