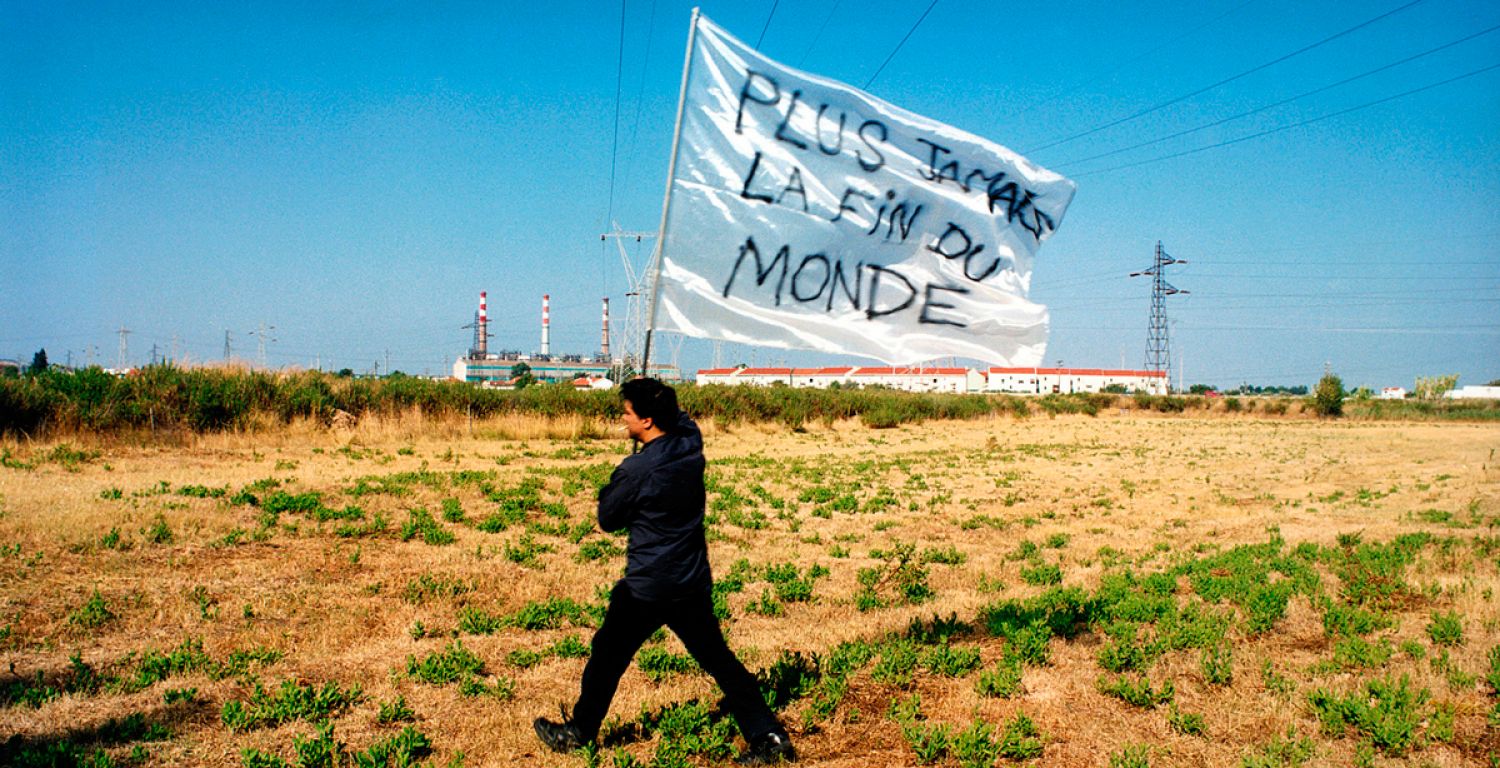

João Tabarra: «Plus jamais la fin du monde» – A Narrative of Disenchantment?

David Santos

The phrase ‘Plus jamais la fin du monde’ is, despite its poor material inscription, the featuring sign-laden element in this work by João Tabarra, not only for its imposing linguistic expression, as opposed to the bright visuals elsewhere in the image, but for the centrality it takes in the composition itself. But let us pause to see what surrounds this slogan phrase. It is inscribed in a nearly transparent flag wielded by a character ‘marching on’, solitary, within a landscape at once rural and industrial, as always happens with the places raided by progress. Art is often linked to this image of ambiguous experience of opposites (either between picture/word, ethics /aesthetics or individual/collective), just remember how Camille Pissarro's impressionism learned to capture this conflictual coexistence between nature and its transformation dictated by the needs and the ambition of men.

And, to some extent, this image by João Tabarra seems to appropriate the impressionist model (not in technical terms – because it is a photograph – but in its aesthetic-formal composition). Notice the horizon line which highlights the imagery field and the landscape theme, or the hedgerows and vegetation that punctuate the intermediate plan, the way the centered character walks, in a somewhat revolutionary stride, by the semi-abandoned ground, evoking, withot any trace of romantic heroics, Delacroix's famous 'Liberty Leading the People' (1830). It's up to the female figure, as allegory of Freedom, to lead to rebellion a set of characters in the French painter's work.

Tabarra prefers an insouciant image of a real man, alone, a cigarette in the corner of his mouth, who, in spite of everything, maintains some kind of dignity. Lost on the decontextualisation of his action in motion, this figure holding the enigmatic flag seems determined to fulfill a certain task that we assume doomed to failure. Let us not forget that, in Tabarra, suspended performativity, the absurd and the poetic constitute the axes for experiencing what still brings us closer to a political reading of our time. Only the politician here is never defined by the precise feature of communication, but rather by the diffuse declaration of a desire, an invitation. Actually, is this a lonely march? Couldn't the isolation of the figure holding the flag be an invitation for us to join it? Isn't that paradoxicality of meaning a call to our solidarity and participation? Between the derisive disenchantment and the willingness to act, this image displays a complex narrative, hybrid in its signifying process, but still impregnated with an affirmative stance, of integrity and hope.

In the set of meanings that this large-scale photography invites us to develop, this slogan is, despite its attractive formal and linguistic centrality, not just enigmatic, as lonely itself, promoting above all an ambiguous feeling between the pamphleteer and the nonsense of its proposal, and between the strength of the action and its absurd, thus creating the conditions for a poetic reading of the narrative. But why is it that we read a strange slogan in that phrase, still an offspring of the great moments of rebellion, but at the same time paradoxical enough to remind us of the postmodern crisis and its dystopian reflux? ‘Plus jamais’ (never more) is perhaps the most definitive and peremptory declaration that language allows us, although mostly contradicted by the future's reality. Its meaning can lead us either to that which will no longer return, or to what it takes time to come, and may constitute the very expression of its impossibility – thus creating an insoluble gap. On the other hand, ‘la fin du monde’ (the end of the world) represents the opposite of the slogan's first half, by promoting a localization, a concrete destiny; but at the same time it also suggests a imperceptible path, because it refers to a far away, almost unreachable distance.

As wrote Emilia Tavares: ‘(...) in this image the concept of simultaneity is explored, where in a time and space that already evokes the end of the world, one protests in order to avoid what has happened already’. That's why True Lies and Alibis – Marche Solitaire by João Tabarra is a work that holds us to the European land and its future, not only because it summons a past disturbed by political and ideological theologies, with their lies, truths and alibis, punctuated in the image by the march and all the military and rebellion stories associated to it, but by the French language as well, inscribed on a flag, which marks a reflexive tradition and also an appeal for voluntary action, still linked to many disappointments, frustrated projects, crises and attempts to reconstruct a mythical or common European ideal. But in the end, the world is not standing, neither its inheritance or its project for the future, but just a man holding the flag, who, as in ancient battles, is at the forefront of an idea, although vague, made of courage and conflict. Always reckless on its purpose and adventure, this desire to take the flag and continue the march is today as it always was, although differently, the mould of all human action, the strength and the engine of the achievements and the defeats that make not just an image, but a common heritage.