Frederico Morais' New Criticism or for an erotics of criticism

Cristiana TejoOn December 13, 1968, the Institutional Act 5 (AI-5) was decreed that hardened the Brazilian civil-military dictatorship, which began in 1964. The year 1969 was inaugurated in a gray, hopeless, opaque mood. In the words of art critic Frederico Morais there were «two times: 68 / joy joy – wonderful divine; 69 / sadness sadness – repression and torture. Two spaces: art – creative explosion, art-activity, art-life – and politics – the overcoming of ideologies»[1]. This would be the year of the international boycott of the São Paulo Art Biennale due to censorship on display at the Museum of Modern Art in Rio de Janeiro with the Brazilian representation chosen for the Paris Biennale and the Salão da Bússola, held at the same institution, in November 1969. This event, which eventually unintentionally launched what became known as the «Tranca-ruas generation», or generation AI-5 (a crop of markedly conceptual and political artists), was coordinated by the aforementioned Frederico Morais, a critic who was totally committed to the renewal of Brazilian art and art criticism.

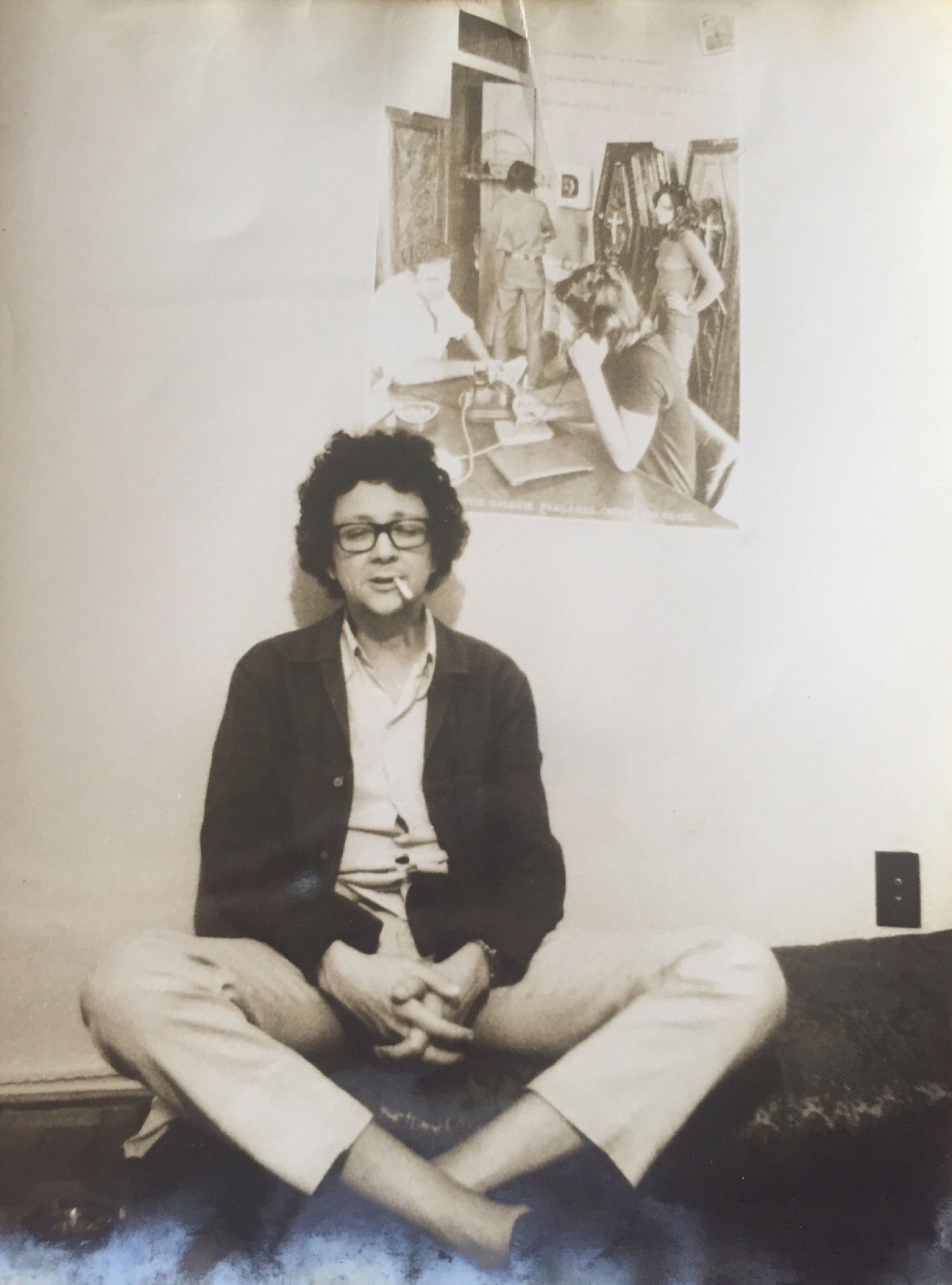

The passage from the effusive 68 to the sad 1969 hastened the gestation of A Nova Critica, a radical revision of the critical practice engendered by Morais. It was a matter of critically commenting on an artist's work or exposition with other work done by the critic using the same artistic language and preferably using the same materials, supports, and venues chosen by the artists. That is, instead of using written language, something that belongs directly to the universe of literature, Morais proposed to use his own artistic vocabulary, something that was not external to art itself. The experiment took place throughout 1970 and paved its new avenues of critical and curatorial experimentation for the next five years.

The basis for the new critique begins to be made explicit by Frederico Morais in his text Against Affluent Art - the body is the engine of the work, published in January 1970 in the Revista de Cultura Vozes, a tribute to Decio Pignatari who had written the «Artistic Guerrilla Theory» in June 1968, also inspired by Marcuse's countercultural thinking. Starting from Pignatari's premises, Morais elaborates a kind of manifesto and battle cry, in which his position in favor of a guerrilla art, which not only responds to Brazil's authoritarian climate and the countercultural moment of the world, is made more explicit, but also buries once and for all the concept of artwork and other beliefs that have grounded art history so far. The guerrilla artist would be the protagonist of a counter-history of art, no longer based on works given to contemplation, but on situations and / or propositions that must be lived and experienced. And in this art war, as in all wars, structures and positions are destabilized, shuffling places and functions. On the front of the contemporary art settlement war, the art critic also becomes a proponent.

The questioning of his role as a critic is taking shape in the exhibition projects that Frederico Morais organizes. In 1966, he curated Brazilian Vanguard, a collection of experimental works by carioca artists who represented the new art. Unable to mount his work, Oiticica asked them to set it up for him. Morais, Rubens Gerchman and Pedro Escosteguy following the artist's instructions built the Bolides, boxes with elemental earth materials (coloured pigments, stones, charcoal). This action of doing the work by the artist reflected the uniqueness of contemporary art and the relationship of the critic with this type of work and awakened in Morais a new process of thinking about possibilities of his own performance.

The project From Body to Earth, conceived in the last weeks of 1969 and materialized in April 1970, is a field for the realization of Frederico Morais' experiments. These were in fact two simultaneous and integrated events: the Object and Participation exhibition, held at the newly opened Palace of Arts of Belo Horizonte and opened on April 17, 1970, and the manifestation of the Body to Earth, held in the City Park, just behind the Palace of Arts, April 17-21, marking the celebrations of Tiradentes[2]. The project was the counter-proposal made by Frederico Morais at the invitation of Mari´Stella Tristão to become responsible for the organization of the Ouro Preto Salon of that edition, which took place exceptionally in the Palácio das Artes and not in the historical city of Minas Gerais. With carte blanche from Tristan, Morais made some modifications to make the event more contemporary. It changed the category of sculpture to that of object and included the Municipal Park as the area of performance of the artists.

Unlike exhibitions organized by artists, in which the producer of the work is also a curator, in From Body to Earth and Object and Participation, Morais sets in motion his process of performing works of art, or his dialogical attitude between word and image, between who writes and who produces, shufling classifications. Fifteen Lessons on Art and Art History – Appropriations, Honors, and Equations consisted of 15 captioned B&W photographs, and as the title itself states, it is about linking images and concepts with artists, thinkers, and artistic styles. It printed the cover of the newspaper of the 7th Ouro Preto Festival.

In the blue squares were a quote «Jan Dibberts: ‘The artwork is the photo of the work’» and a text – instruction: «The body is the engine of the work – Walk through the exhibition on foot. After seeing, move and imagine the works, stop for a moment anywhere in the park, or sit or lie on the grass. Breathe deeply. Listen to your heartbeat, take your pulse, feel the sweat and tiredness in your body. The work is ready and finished». The images were photographs of Maurício Andrés Ribeiro, many of them made in the park itself. Morais tells in several testimonies that he knew the City Park very well because in pre-adolescence he sold sweets there and had a biographical and affective connection with that space. A self-taught art historian, he elaborates his first work creating a new art history that intertwines with his own personal trajectory.

There was no catalogue of any of the two projects, only the Body-to-Earth Manifesto written and signed by Frederico Morais, which was distributed at the opening, besides being published in the newspapers of the time. Divided into nine parts, one of its passages reads: «Today's art reflects nostalgia for the body. The body and its universal dimension, its relation to the fundamental rhythms of life itself. Natural and organic rhythms. The body as a lung of existence. Systole and diastole – breathing and perspiring. Blood as the communication element of all men. Like the sweat. The body – head, trunk and limbs. All senses and not just sight. A tactile-olfactory code. A taste grammar. An acoustic language. The other senses determine circular spaces, therefore dynamic. The groping hand, the walking body, smell-imagine. And participate».

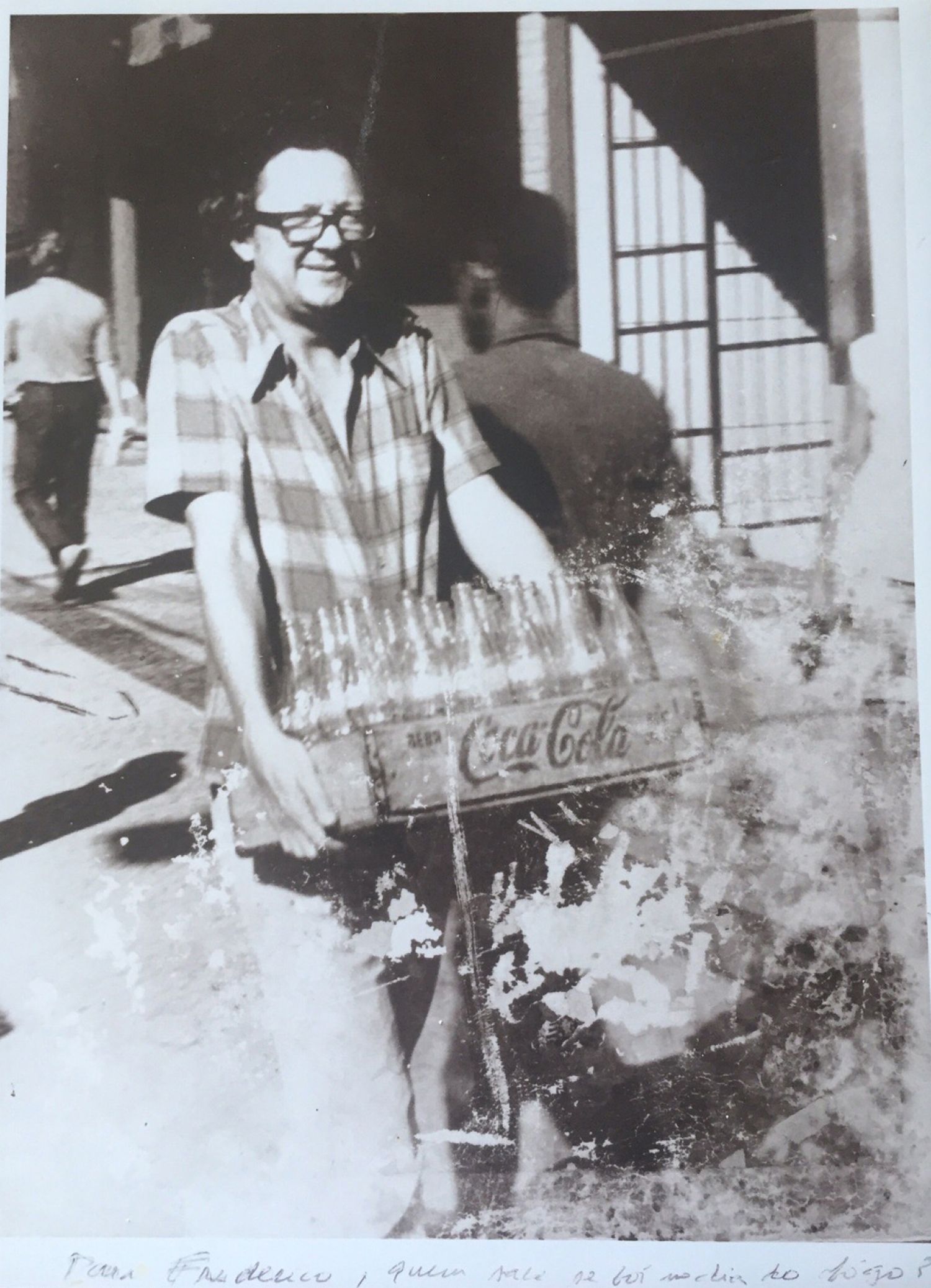

Three months after the curatorship experience of Object and Participation and Body-to-Earth, and mainly after having produced fifteen Lessons on Art and Art History - Appropriations, Honors and Equations, Frederico Morais debuts The New Criticism at Petite Galerie, in Rio de Janeiro, as a critic to the exhibition series Agnus Dei, by Thereza Simões, Cildo Meireles and Guilherme Vaz. The first show was the one of Simões and gathered blank screens but with titles that described situations. Meireles was the second artist to exhibit and show photos that recorded his work presented at the manifestation of the Body to Earth manifestation and the pole in which he sacrificed the chickens, as well as three bottles of coke, from the Insertions in Ideological Circuits project. The show that ended the cycle was Vaz's, and comprised a notice at the entrance of the gallery of «dispossession» of all visitors.

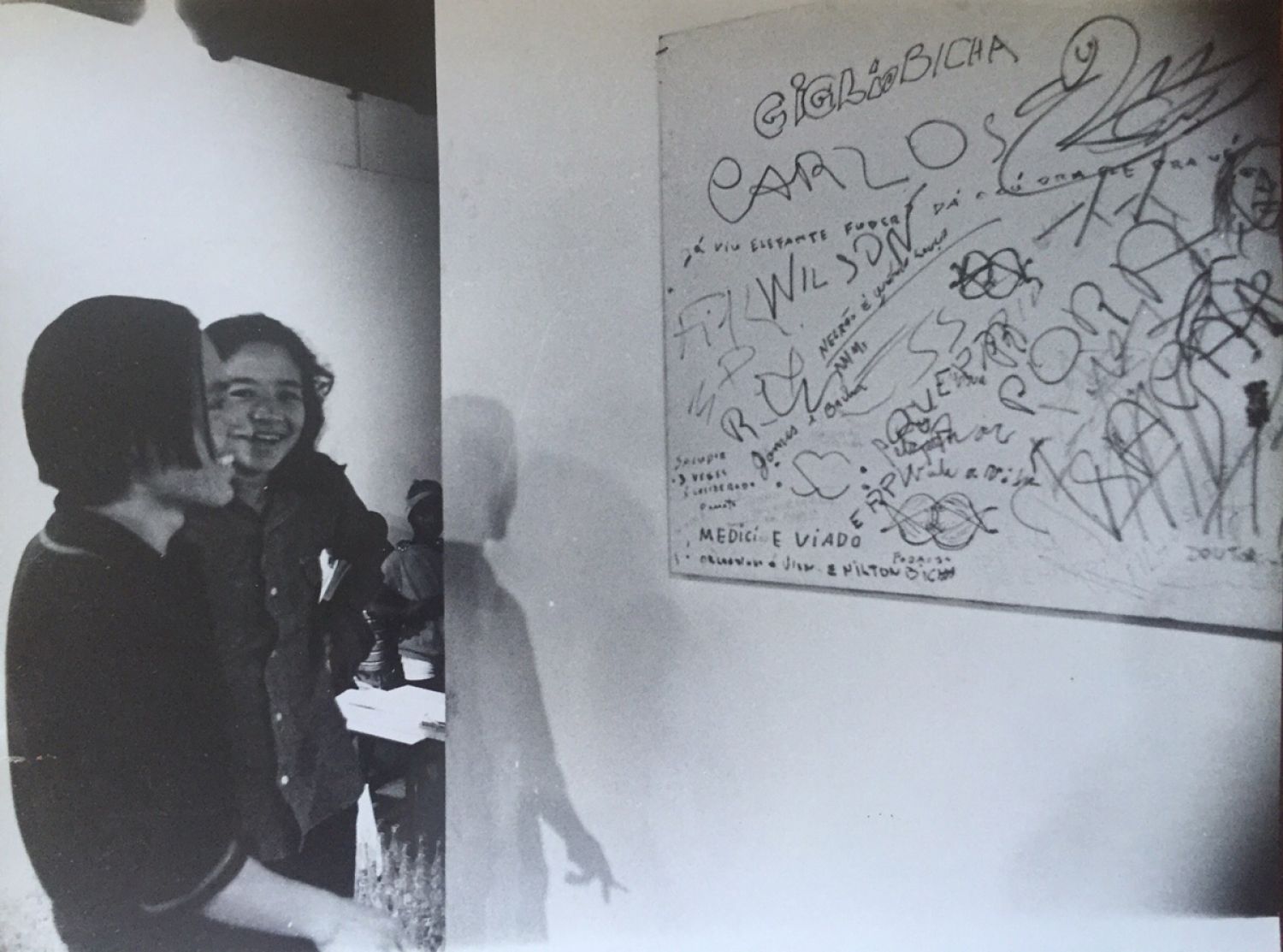

Frederico Morais's critical response to Agnus Dei, in terms of The New Criticism, was his homonymous exposition on 7/18/1970. In it, she answered Thereza Simões with the presentation of the spoils of originally white canvases placed in urinals of bars located in Tijuca and Ipanema (the first half destroyed after the first bad word written, and the second, with blunt criticism of the Medici government). About Cildo Meireles' works, he commented on 15,000 empty soda bottles, «kindly provided and transported by Coca-Cola Refrescos SA», as well as photos of a monk immolating himself in Vietnam, captioned by biblical texts of Genesis and Exodus. (MORAIS, 1995). The dialogue with the work of Guilherme Vaz was the replacement of his document which he had called the «Project of Exhibition for Mass Scale Murdering» by another, expropriating the first, in a clear irony about the symbolic gesture of institutionalized agents. On one wall, Morais placed a panel with a kind of introduction to the New Criticism action with excerpts from articles and essays he had noted since 1958. The critical exhibition lasted only a few hours and was closed under threat of invasion of the gallery by the police.

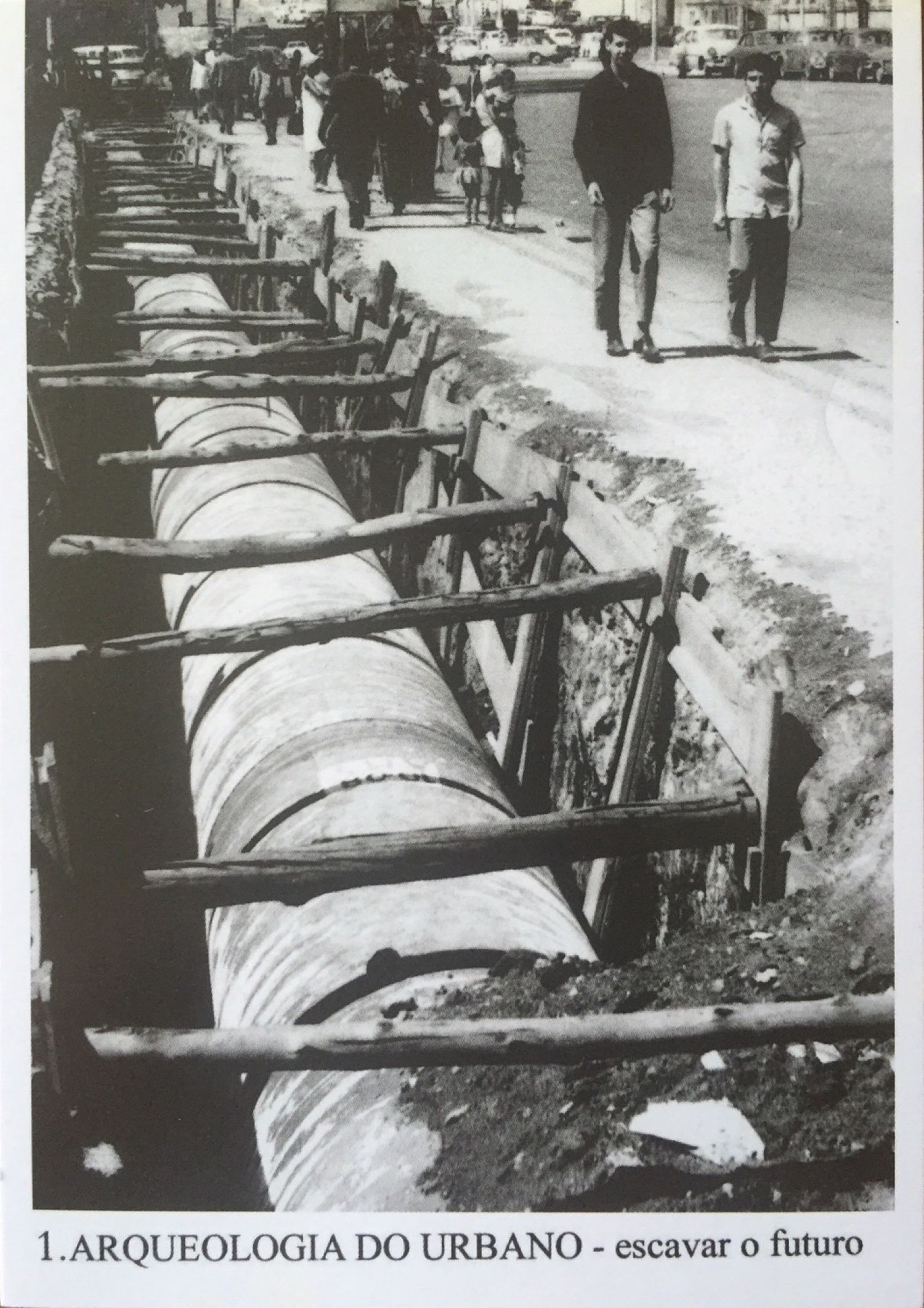

The second comment Morais made in terms of The New Criticism was in the form of an audiovisual, in which were confronted images (slides) of the works presented by the artists from São Paulo, José Resende, Luiz Paulo Baravelli, Carlos Fajardo and Frederico Nasser, at MAM-RJ with images of the city's construction sites, drawing the viewer's attention to what he called «archeology of the urban», already rehearsed in his presentation of Body-to-Earth. The images were complemented with a kind of sonorous memory of the city: sounds of hydraulic hammers, workshops, bells, dripping water, images that flowed along with texts by Bachelard, Molles and Langer. This was the moment when he sought audio-visual resources for his critical comment.

In November 1970, Frederico Morais made another audiovisual commenting on works by Artur Barrio, Everyone’s Bread and the Blood. Both audiovisuals and a third, Cantares were awarded at the II National Salon of Contemporary Art of Belo Horizonte. This was the first time that a Brazilian salon recognized audiovisual as an expression of current art, opening an unlimited field for artists (MORAIS, 1973) the one of projected image. In fact, the New Criticism ends with Cantares. From it, audiovisuals gained autonomy as works of art, perhaps because of the difficulty in maintaining a dynamic rhythm of criticism from exhibitions or because the process itself became artistic in itself for Frederico Morais.

During the last year of the 1960s, the text Criticism and Critics[3] would still be published, another platform for the enunciation of the context and precepts of The New Criticism. The article aligns the crisis felt in a Brazil gagged by dictatorship and the dispute over meaning about cutting-edge art and the theoretical discussions that took place on this issue in other parts of the world. It presents the clash between the effort of professionalization of criticism, such as the structuring of fee tables, the obligation of critics in art juries and the awareness of the precariousness or even uselessness of aesthetic judgment: «In fact, it is an older question with a deeper and philosophical background. It concerns judgement. This is question is particularly aggravated at the present time when the total failure of isms, genders, plastic values is followed by unlimited openings». He summarizes: «The current scenario seems to be as follows: on the one hand we have the judicative criticism, setting criteria, on the other, the new criticism, opening the process, seeking to make criticism a creative act».

In contrast to the critical positivism or the figure of the critic as a judge, mentioned in texts by Lionelo Venturi, Eduardo Portela and John Dewey, Morais defends criticism as a creation based on Roland Barthes' thinking about writing, understood as the exercise of freedom and fruit of historical conditioning. In his words: «Now if criticism is not judgment (condemn creation) it is creation (which excludes judgment). Can you accept this? Not in absolute terms, for judgment does not strictly exclude participation that must be understood as creation, just as creative criticism does not exclude judgment. What is refused is the oppressive authoritarian criticism, which, in the name of a hierarchy of values, submits the work of art to absolute and unmodifiable criteria... The less judgmental and partial the more creative art criticism is. (…) The critique thus exercised is, in fact, a transformative activity that creates simulacrum, a «structural activity», as Barthes says… All criticism of the work is a critique of itself. (…) Create a new text. The critic becomes an artist. In fact there is no longer a separation between criticism and art, there is only what, on the subject of literature, Barthes calls «écriture», saying that in this new situation of «general crisis of the comment»[4] the critic becomes in turn a writer.

Twenty years afterwards[5], Frederico Morais would add love and eroticism as seminal components to his understanding of the exercise of criticism and theorizing of art. He claims that one of his greatest fantasies was to write a kind of affective history of art, in which the affectivity of form would be discussed, just as the critic's passionate relationship with the work would be the most advisable way of understanding the meaning of artistic creation. In addition, he wanted to «show how the affective relationships between art producers or between the creators and their private world sometimes impact decisively on artistic creation». He reinforces his reasoning with the statement: «I believe in a loving, engaging and involved criticism. Like Susan Sontag, I propose to replace hermeneutics with an erotic of criticism, boring and pedantic speech with loving speech. (…) To be fair, that is, to have its raison d'être, criticism must be partial, passionate and poetic, that is, made with an exclusive point of view, a point of view that opens horizons»[6].

Fifty years after its emergence, perhaps the great legacy left by The New Criticism is this call to approach and understand art with the whole body, with all its senses and potentialities. Emerged during the Année Érotique and the pulsar of one of the most oppressive phases of Brazilian history, Frederico Morais' proposition is still one of the most potent attempts to minimize the primacy of rationality by pointing to its limitation and to generate a creative, affectionate interaction, intelligent beyond the established and the recognized. Possibly, in the present world moment it is important to return to this call for eroticism, for an erotics of art, of life, of criticism.

Footnotes

- ^ Frederico Morais, «Como será você, geração 90?», In: Crônicas de Amor à Arte, Rio de Janeiro: Revan, 1995. Published as Artes Plásticas, in the catalog of the exhibition 68x88 no Balanço dos Anos, realizada na Escola de Artes Visuais do Parque Lage, 1988.

- ^ Joaquim José da Silva Xavier, known as Tiradentes, is a symbol of Inconfidência Mineira, a Brazilian separatist movement that took place at the end of the 18th century, in Minas Gerais, Brazil. Since the Republic, the date of its execution, April 21, is a national holiday.

- ^ Revista GAM, Rio de Janeiro, n. 23, 1970, pp. 30-32.

- ^ Frederico Morais, Revista GAM, Rio de Janeiro, n. 23, 1970, p. 32.

- ^ Frederico Morais, Por uma Crítica criativa – a curadoria de exposições como criação. 2o encontro da ANPAP, São Paulo, 1989.

- ^ Apud. p. 123.