1/1 b&w reproduction

Mariana Pestana & Joana M. PestanaFrom the erosion of architectural surfaces’ pigments in Ancient Greece to the dissemination of modernist architecture through black and white images, this text speculates about the errors of reproduction that might lay behind the deprivation of colour, which characterizes the western architectural landscape today.

«For me grey is the welcome and only possible equivalent for indifference, for the refusal to make a statement, for lack of opinion, lack of form.» (Gerhard Richter. (1975), «Letter to E. de Wilde»)[1]

To state that colour is a superficial architectural element does not cause much strangeness. The binary distinction between line and colour seems to be an old one (already in Aristotles’ Poetics a hierarchy between the two was postulated) and to rest on the predominance of the former – of the domain of reason – in relation to the latter – of the domain of the senses[2].

When one opens a dictionary and finds the verb ‘to colour’ featuring as a synonym of disguise or ‘coonestar’ (to appear honest), one begins to understand where the fear of corruption through colour that characterizes the modern chromofobic architect might come from. Often described as secondary, dangerous, feminine and threatening[3], colour has been frequently marginalized in the intellectual circles and discourses about the built environment. Two main ideas give structure to such marginalization. The first excludes colour from the domain of the material that it covers: it situates colour in relation to the space of the other by associating it with the universes of the feminine, oriental or queer. The second establishes that colour is not an element in its own right and therefore determines that colour is superficial, supplementary, non-essential, cosmetic.

Reproduction Error I

To evoke the classical antiquity without mentioning colour at all also does not cause huge surprise: white marble and exposed limestone are part of the collective imaginary of classical architecture and sculpture, way more than the strong colours that, indeed, comprised it. When in the beginning of the sixteenth century sculptures such as the famous group of Lacoonte were found, it was thought that the material (white marble) had never been coloured before (colour, with the passing of time, would have faded). This fault – to consider the naked marble as «genuine» – has had immense repercussions since it grounded the reproduction of incomplete classical models (without colour) which would eventually define the formal language of the Renaissance.

The use of materials in their «natural» state, without cover or painting, served the celebration of the principle of truth, which was believed to characterize the Greek and Roman ancient architecture and sculpture. For the first time in history, colour was disassociated from architecture: until then colour and form had remained inseparable[4]. (Think of Bizantine, Middle Ages, think of other places like Asia or the Mediterranean Moorish caliphates!). In the sobriety of Renaissance, colour was allowed in so far as it was intrinsic to the material, and suppressed when exerting the function of covering.

Erratum

Hundreds of years after the Renaissance, also the neo-classicists looked to reproduce the fundaments of classical antiquity. But the interpretative fault that justified the absence of colour in Renaissance was no longer reasonable in the neoclassical period because the use of colour in classical antiquity became evident in the nineteenth century. Instead, the monochrome was not a mistake but rather a collective conspiracy[5], a kind of conscious amnesia: the polychrome was purposefully ignored.

The orienting principles of Neoclassicism defined by Johann Winckelmann considered that colour should play a minor role in the construction of «beauty» because it was structure – not colour – that constituted its essence[6]. And yet the Grand Tours and expeditions of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries unburied fragments of coloured masonry in Greece and confronted architects and archaeologists with a crisis of such principles. In An Apology for the Colouring of the Greek Court in the Crystal Palace, Owen Jones recounts the hesitation and insecurity that characterized the process of reproducing the classical model of the Greek temple in colour at the Great Exhibition of 1851 in Crystal Palace:

«(...) I felt that to colour a Greek monument would be one of the most interesting problems I could undertake; not indeed in the hope that I might be able completely to solve it, but that I might, at least, by the experiment remove the prejudices of many.»[7]

Thirty-five years later, in 1886, archaeologist Georg Treu showed a coloured classical antiquity in the Royal Academy of the Arts in Berlin, rectifying at once the belief that it had always been white[8]. Even though the prejudice was removed, colour continued to have a relatively secondary role in the dominant conceptions of architecture.

Reproduction Error 2

During modernism, notions like expressive truth, structural truth and historical truth were consolidated, and they corresponded to a wish for respecting respectively the spirit of the architect, the properties of the materials that formed the building and the language of the time in which it was built[9]. According to such principles, honesty could be practiced in the act of revealing – instead of covering – the building materials and celebrations – instead of hiding – structural elements.

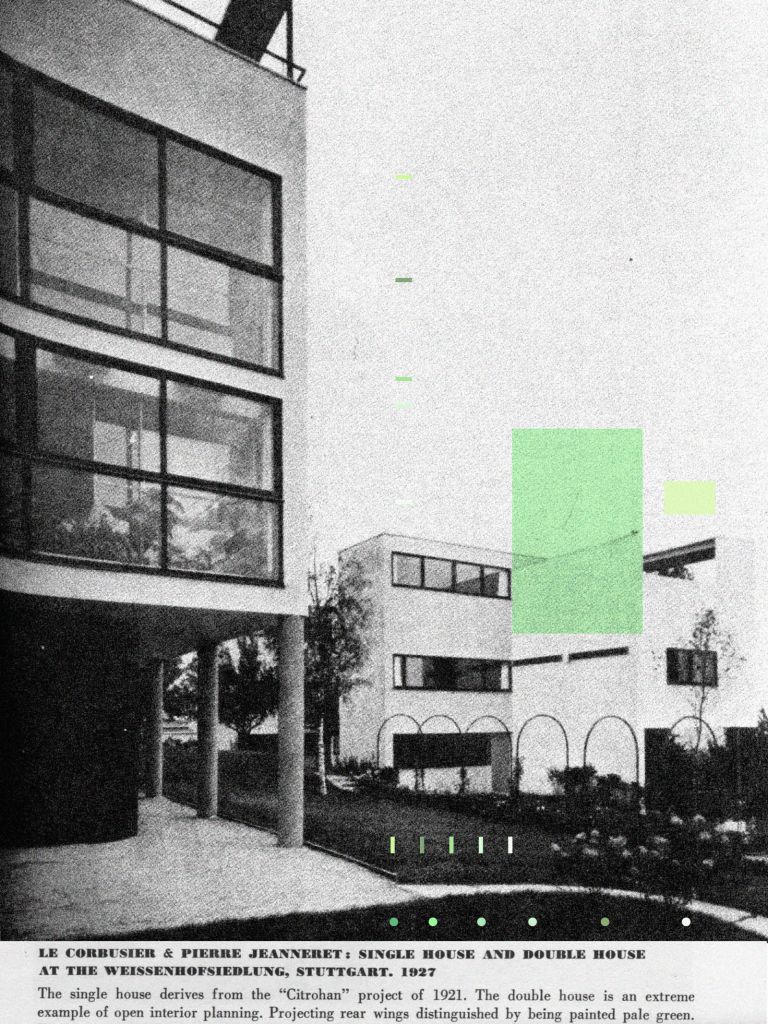

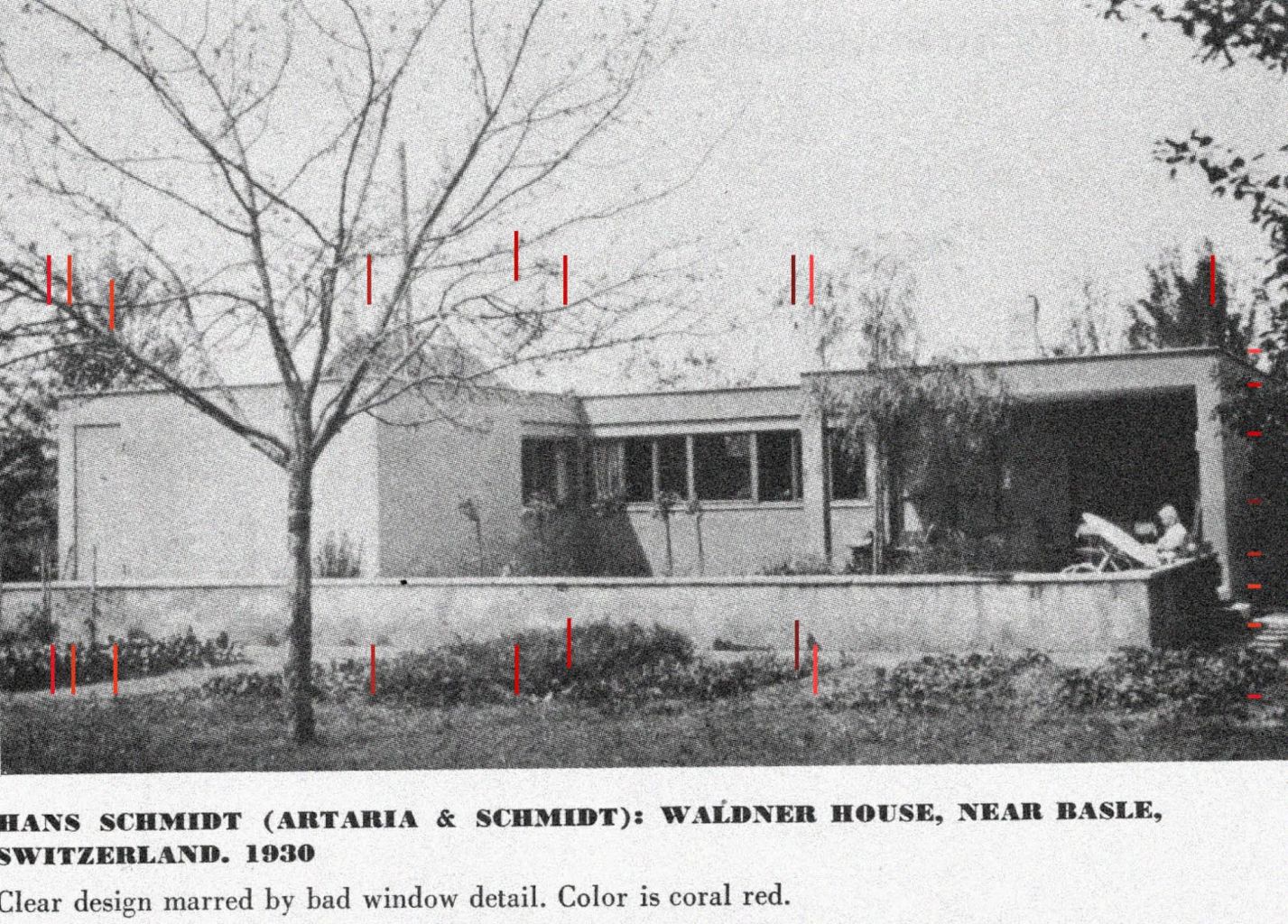

When in 1932 Philip Johnson and Henry Russel Hitchcock organised «The International Style» exhibition at MoMA in New York, through a series of projects carefully disposed side-to-side they accentuated similarities and attenuated differences, constructing the idea of a universal style that rested on the simultaneities of a restricted sample of buildings. The catalogue was a fundamental player in the dissemination of the message beyond frontiers, an important means of making the «style» truly international. Printed in black and white, the catalogue replaced the colours of buildings – blue, red, yellow amongst others – for a scale of greys, and the information about the real colours was remitted to the captions, as accessory, in a secondary position. As a means of communication, the catalogue diffused an image of architecture in black and white, and therefore the dominant look of modernism was built from a lack of colour. Due to technical or budgetary limitations, the catalogue ended up contributing to the concealment of a formal element and therefore deflected from truth. Once again architecture was reproduced without colour. Yet again colour was marginalised by a movement anchored to the principle of truth. And again, it was submitted to a secondary position, subjugated to form.

Errata

Today, the truth about the use of colour in classical antiquity is widely recognised. The touring exhibition «Gods in Color: Painted Sculpture of Classical Antiquity» (2007), curated by archaeologist Vinzenz Brinkmann, displayed originals of Greek sculpture against their reconstructions with the aim to definitely annul the misunderstandings around white sculpture: through the use of ultraviolet waves, the original colours of each piece in exhibition were decoded. This technique was developed in the Department of Conservation and Scientific Research at the British Museum and it revealed remains of blue pigment (Egyptian blue) in sculpture pieces that belonged to the original Partenon. Finally, the idealization of Greek sculpture and architecture as white was proved wrong. Nowadays, modernist architecture colour photographs are prolifically circulated, eliminating any doubts about the variety of colours that characterized it. And yet, the colour white seems to dominate the contemporary western architectural landscape. Might the architect, still today, be scared of being corrupted by hiding the true materials? Might he fear associating with the concealed, the feminine, the queer, the superficial? What is it that leads so many architects to build in white? Interpretative errors, repetition of modernist models, classical praise? The scholarly monochromatic consensus of today is grounded on a series of mistakes – conscious or not – of historical reproduction. It rests on a base of classical truth that is, in fact, barely solid, and it results from centuries of accumulation of copies, imitations, reproductions and duplicates, all incomplete.

Footnotes

- ^ RICHTER, Gerhard. (1975). «Letter to E. de Wilde» in BATCHELOR, David. (ed). (2008). Colour. London: Whitechapel and MIT Press.

- ^ BATCHELOR, David. (2000). Chromophobia. London: Reaktion Books, p. 23.

- ^ BLANC, Charles. (1874). «The Grammar of Painting and Engraving». New York, in BATCHELOR, David. (ed.). (2008). Colour. London: Whitechapel and MIT Press, pp. 32-34.

- ^ SOLON, Léon Victor. (1918). «The Greek System of Architectural Polychrome Decoration». The Architectural Record, Vol. XLIII, N.º 4 (April).

- ^ JENKINS, Ian interviewed by Jo Marchant, «The Partenon in Colour» http://www.decodingtheheavens.com/blog/post/2009/06/15/The-Parthenon-in-colour.aspx (consulted 3 Feb. 2015).

- ^ HÄGELE, Hannelore. (2013). «Neoclassicism: What Happened to Polychromy?» in Colour in Sculpture: A Survey from Ancient Mesopotamia to the Present. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 253-254.

- ^ JONES, Owen. (1854). An Apology for the Colouring of the Greek Court in the Cristal Palace. London: Bradbury & Evans.

- ^ LOBELL, Jarret A. (2013). «Not Quite Ancient». Archaeology, Vol. 66, N.º 4 (July - August), p. 10.

- ^ FORTY, Adrian. (2000). Words and Buildings. A Vocabulary of Modern Architecture. London: Thames & Hudson, pp. 289-303.