Aesthetic trap and historicization in «Antichrist», by Lars von Trier

Patrícia KrugerWhen Antichrist, by Danish director Lars von Trier, premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in 2009, it caused a notable controversy and divided opinions. While many people considered it a masterpiece, and Charlotte Gainsbourg was even awarded the best actress prize, there were also those who demanded that Trier explained why he made that film, who considered it abominable or the proof of the director’s misogyny. My argument concerning the film is that the female oppression is not endorsed by the work, but exposed and problematized by several elements that complicate the realistic interpretation of Antichrist and the direct association between the materials that it brings to the debate and the point of view of the film.

In this sense, it might be interesting to observe Lars von Trier’s statement in an interview given shortly after Antichrist’s release: «A very important thing to say is that whatever a film is about, it is not what the director thinks about things. And a big part of, actually, my technique is to put up a thesis of some kind that I do not agree with. I don´t believe that there were suddenly bells in the sky, I don’t agree with it, or that this religion is better than any other religion [references to the film Breaking the Waves]. […] That goes for all of my films»[1].

Lars von Trier and The Narrative Focus

Such as in other narrative constructions, what detaches the ideas present in a film from the point of view presented by the whole of the work is precisely a very important device – the narrative focus of a film. If we pay attention to the Lars von Trier’s filmography, we will notice that the structuring of the narrative focus is always very complex and a central element to analyse his films. In his first trilogy, Europa (The Element of Crime, 1984, Epidemic, 1987 and Europa, 1991), for instance, the narrative focus is associated to masculine protagonists – idealist heroes, with noble ideals, who, nevertheless, end up disseminating misfortune along their ways. To illustrate the doubts and concerns of these heroes, several daring stylistic and technical resources are used, helping to merge the spheres of «real» and «imaginary». The audience is thus closer to the psychic processes of these characters, what makes such films distant from the realistic formatting so dear to the hegemonic cinema, and closer, indeed, to an expressionist or even an epic formatting, in the sense of the Bertolt Brecht’s dramaturgy.

In his following trilogy, Golden Hear (Breaking the Waves, 1996, The Idiots, 1998 and Dancer in the Dark, 2000), the narrative focus shifts to female characters. Instead of acting in the name of idealistic causes, with tragic consequences for other people, theses heroines are victims of their own «golden hearts» and end up sacrificing themselves in a world that fails to recognize their fair motivations. In such works, Trier continues to bet on several resources to express the subjectivity of his main female characters, including the absurd bells that appear ringing in the sky at the end of Breaking the Waves, or the abrupt insertion of the musical form in the more «realistic» structure of Dancer in the Dark. Regarding the latter, such inclusion illustrates the desires, fantasies and escape from reality that Selma, the main character, needs to create to handle the difficulties of being a nearly blind foreign worker in the United States.

We can also refer to his next trilogy (USA: Land of Opportunities) ‒ which actually only had two films, Dogville (2003) and Manderlay (2005). In such films, the question of the narrative focus is make explicit not only by the use of an unreliable voice-over narrator, but also by presenting a protagonist (Grace) who works as centre of conscience of the film and takes that enhance the controversy of both Grace and the narrator’s ideological perspectives. With the support of such structural device and of the unrealistic stage-like set, the understanding of cinema as a construction and exposition of selected standpoints is made very clear. Hence, both films throw open the influence of the Brechtian Verfremdungseffekt (defamiliarisation effect) on the works of Lars von Trier, which helps to dismantle the dramatic illusion and stimulates the audience to estrange social processes and events understood as «natural».

The troubling of the realistic approach in Antichrist

I claim thus that also in Antichrist it is important to notice how the narrative focus is structured and how stylistic arrangements, such as the reappropriation of expressionist and epic forms, impair the realistic, purely dramatic approach to the film. The use of such forms troubles the comprehension of the film as a faithful portrayal of the reality, a «slice-of-life» and, by doing so, impel the distancing and the critical access to the subjects that the film presents, offering the denaturalization of ideological constructions. In this sense, a hyper-realistic approach to the film, focused only on its plot ‒ the story of a couple that loses a child, isolates itself in a hut in the middle of the forest, where the male protagonist tries to cure the suffering of the female protagonist, a researcher, through cognitive therapy, discovering, however, «the intrinsic evil of his wife» and being led to murder her ‒ is quite limited.

Admittedly, Antichrist invites us to go beyond its dramatic aspects, observing the elements of the film that disrupt the uncritical identification of the spectator and his immersion in a story that claims to be «neutral». Some examples are the division of the film into prologue, chapters and epilogue; its strong symbolic and dream-like aspects; the commentaries that the prologue’s aria and the documentary images of witches in the attic make to the film; the inclusion of fantastic elements that break the narrative linearity, as the talking fox; the editing of the film, with the far from harmonic transition from one take to another (exposing thus the film as construction); the characters that suddenly look at the camera, among other estrangement strategies.

The namelessness of the characters also indicates that they represent groups, social functions ‒ men and women. At the same time, following the Brechtian dialectic dynamics between collective and individual, these characters are historically situated: a North-American nuclear family consisting of two intellectuals situated at the present time.

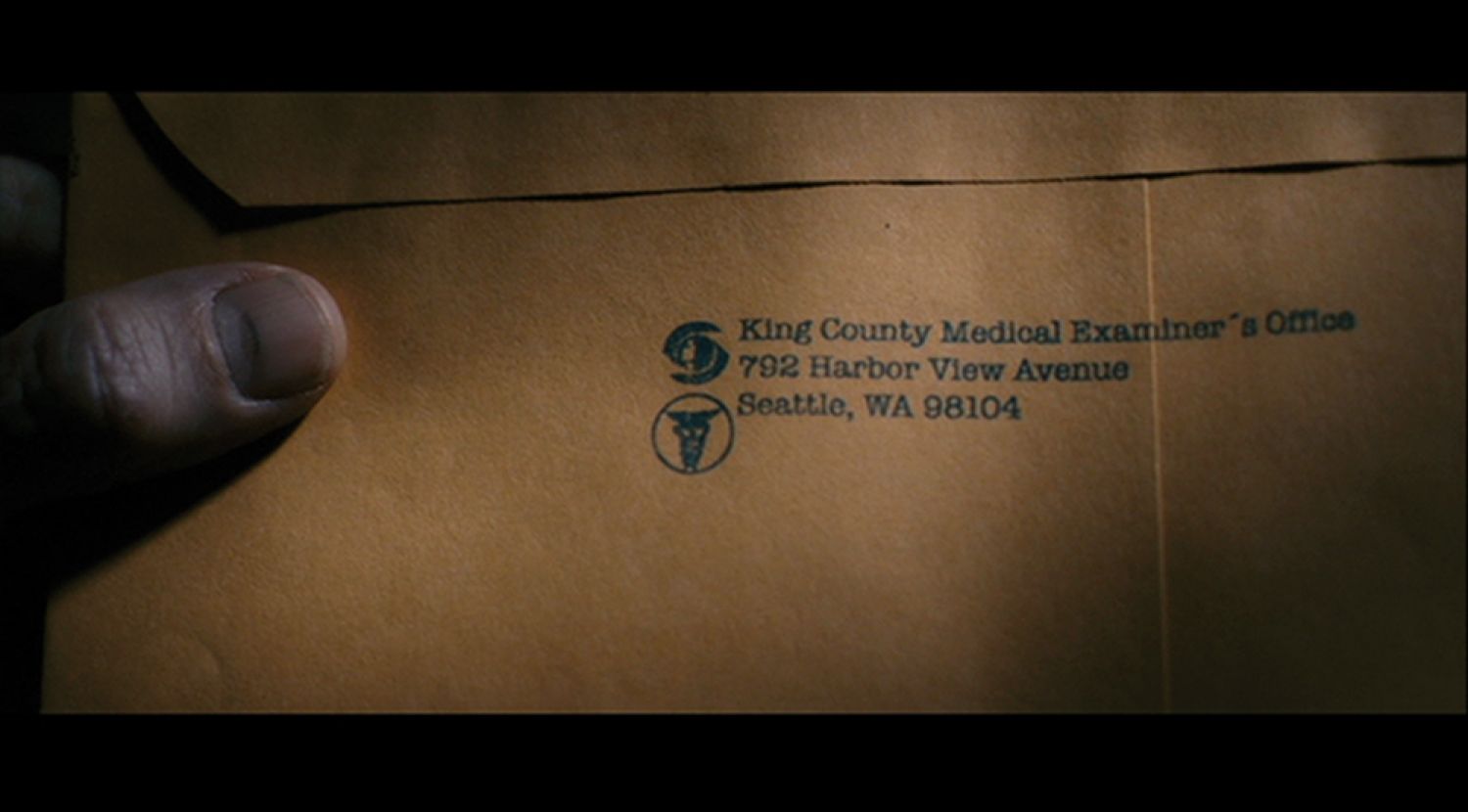

The fact that the film has the city of Seattle as a backdrop, something largely ignored by critics, is an element that must also be taken into account, as the United States is the cradle of the cognitivist therapy that the male character applies without success in the film. It is also a reference of capitalist society and the country that has exerted the greatest political and cultural influence in the world for decades, facts that Trier has criticized in several of his works. The issues concerning women’s oppression in Antichrist must thus be addressed in a dialectical way that responds to the inter-relation between the social-historical plan and the individual/subjective plan, including his/her psychic construction.

Ideological Trap

Hence, we come to another largely ignored fact about the film, which is essential to its interpretation: a strategy called «ideological trap», namely, an artistic elaboration that allows a deceit, a mystification to be interrogated and undone. It is a very recurrent strategy in Lars von Trier's cinematography, as in the game that the director establishes in Dogville, for example, in which the audience is deluded, by dramatic means, and led to adhere to Grace’s discourse, the other characters’ discourse and even the narrator’s discourse[2]. That is all set up only to bring out the moralistic, conservative and sometimes totalitarian repertoire of these spectators (and critics), who delights in Grace's revenge. In Antichrist, this trap is built with the structuring of the film by means of a particular narrative point of view, linked with the male character. This narrative of the therapist, presenting a particular world view, is inserted in a larger structure, the point of view of the film, which comments, refutes, disturbs and puts to test this character’s version of the facts.

The evidence that he is the one conducting the narrative is scattered throughout the film, underlining his central role in shaping the story. We have only to observe that the subjective camera is frequently related to the therapist’s look and that very few scenes have the isolated presence of the researcher, unlike the several ones in which he is the only one present. Let us also remember that he is the only one to witness the fantastic events of the film, as the famous fox scene. In addition, editing, lighting, and the great discrepancy in the amount of speech in the film also help to privilege the therapist as the conductor of the narrative. In relation to his wife, the therapist is the one who holds the most essential knowledge: he has information about the passage of time, he attests to the uselessness of remedies, decides where they should go to and when they can or cannnot have sex. He decides how she should breathe and walk, he determines that she should think and feel in a rational way and where her fears are rooted.

We should, however, be aware of the risk of adhering to this character’s narrative, an adherence that is fed by his being a therapist, a man of Science, of Reason, willing to help his wife overcome the trauma of losing a child. Nothing more honourable! Our task, nevertheless, is to realize that, just as he is leading his wife by use of his rational approach to healing the pain, he is also leading the audience to share his perspective, as if it were the very perspective of the film.

In consequence, the narrative point of view linked to the male protagonist works similarly to the unreliable speech of a first-person narrator, but with an important increase: here, instead of a linear, realistic narrative, we have the materialization of the psychic sphere of this character, as if the film illustrated the veiled, but historically conditioned, mental processes of a particular subjectivity. This ideological trap also brings up the relations between these veiled processes and certain hegemonic discourses, such as ideologies that establish what the «feminine» is and how this «entity» should be controlled in order not to threaten the validity of the patriarchy.

Antichrist as a Strindbergian exposure of hidden psychic events

The constellation of unreal images and events and the numerous references to the universe of dreams and to Freudian theories in Antichrist constitute, in fact, rather a rich exposure of hidden psychic events, linked to a particular ego, in relation to and from which all these events occur, than a properly dramatic reality. This arrangement is made in a similar way as were several plays by the Swedish playwright August Strindberg, such as The Father (1887), Road to Damascus (1898) and A Dream Play (1902). In all these plays, as well as in Antichrist, instead of intersubjective relations, characteristic of drama, what comes about are unfoldings of the very protagonist’s psyche.

If we take the play The Father, for instance, we can notice that beyond the apparent family drama and direct representation of the struggle between father and mother for determining the fate of the daughter, what comes to the surface, in a deeper analysis, is the timeless struggle between men and women projected exclusively from the perspective of its title-character, the father. I quote Peter Szondi in his analysis of the play: «More important is to recognize that the struggle of his wife against him only reaches, in a general way, the ‘dramatic’ realization as a reflection in his conscience, and that the protagonist himself defines his main features. The most important weapon of his wife, the doubt about the paternity, is given to her by himself, and his psychosis is witnessed by one of his own letters, in which he writes that he fears for his reason»[3].

Still in relation to the play The Father, it is possible to observe how Laura is actually not depicted as a well-built character or as another subjectivity with whom the Captain enters in conflict. She encloses, in fact, in a symbolic way, all the «threat» that the concept of New Woman represented to the social patterns of the time. She matches then an imaginary of devilishness, witchcraft and evilness (also present in Antichrist) which serves to justify, from the perspective of the subjectivity externalized in the play – the father –, the danger of «emasculation» that the feminine conquests of the time could bring with it.

In a similar way, the key argument justifying the madness of the female character in Antichrist – the identification with the thesis she was supposed to criticize – is also a transference to the woman of assumptions proper to the subjectivity whose externalization takes place in the film: the therapist’s. He suspects of thoughts and ideas that might occur in the researcher’s mind and project them onto the screen as her words and actions. As in many plays by Strindberg, in Antichrist, too, there are patriarchal interests of the white, male, middle-class intellectual in painting the wife in the colours of madness and cruelty, projecting on the opposite sex his own anxieties and fears.

Reading against the grain

This projection of thoughts belonging to the therapist over the researcher can be better illustrated if we rely on some scenes. In the couple's dialogue at the hospital, in the very beginning of the film, for instance, we see her assuming the blame for the child’s death: «Therapist: There is nothing atypical about your grief. Researcher: It was my fault. Therapist: What about me? I was there too... Researcher: I could have stopped him... Therapist: No. Researcher: You didn't know that he started waking up lately. I was aware that he would sometimes wake up and crawl out of bed...and walk about...just as you thought that he was soundly asleep».[4]

As all the other scenes of the film, this is also part of the construction of reality according to the therapist’s view, serving to make it more comfortable and suitable to his social position and his perception of the world. Therefore, his own convictions – «it was her fault», «she could have prevented it», «she knew this could happen, while I knew nothing» – are projected in the statements and actions of the other character, becoming less condemnable than if exposed by or referring to himself.

The version of the facts exposed by the male character is, nevertheless, problematized by the point of view of the film, which causes the therapist's narrative to present some «faulty actions» or «Freudian slips» in his own discourse. The scene in which we see the researcher clearly watching her son falling off the window, also a projection of the therapist’s mind, is repeated, for instance, a few minutes later with the absurd presence of a deer inside the couple's apartment. This animal, not by chance, had been previously observed, by the therapist only, carrying a dead foetus next to the body. Its reinsertion in the film shortly after we see the researcher watch the kid die confirms the projection of a desire arising solely from his mind, namely, the wife’s consent of the child’s death.

Another example is that we see on the screen, right after the shot of the deer in the apartment, a non-existent constellation, which the therapist also sees, at the same time that he affirms: «there is no such a constellation!». Therefore, the film's point of view expresses the contradictions of the work and challenges the «truths» presented by the therapist’s psychic projections, prompting the viewer to discern, in a Brechtian way, the questions placed in the bosom of apparent evidences.

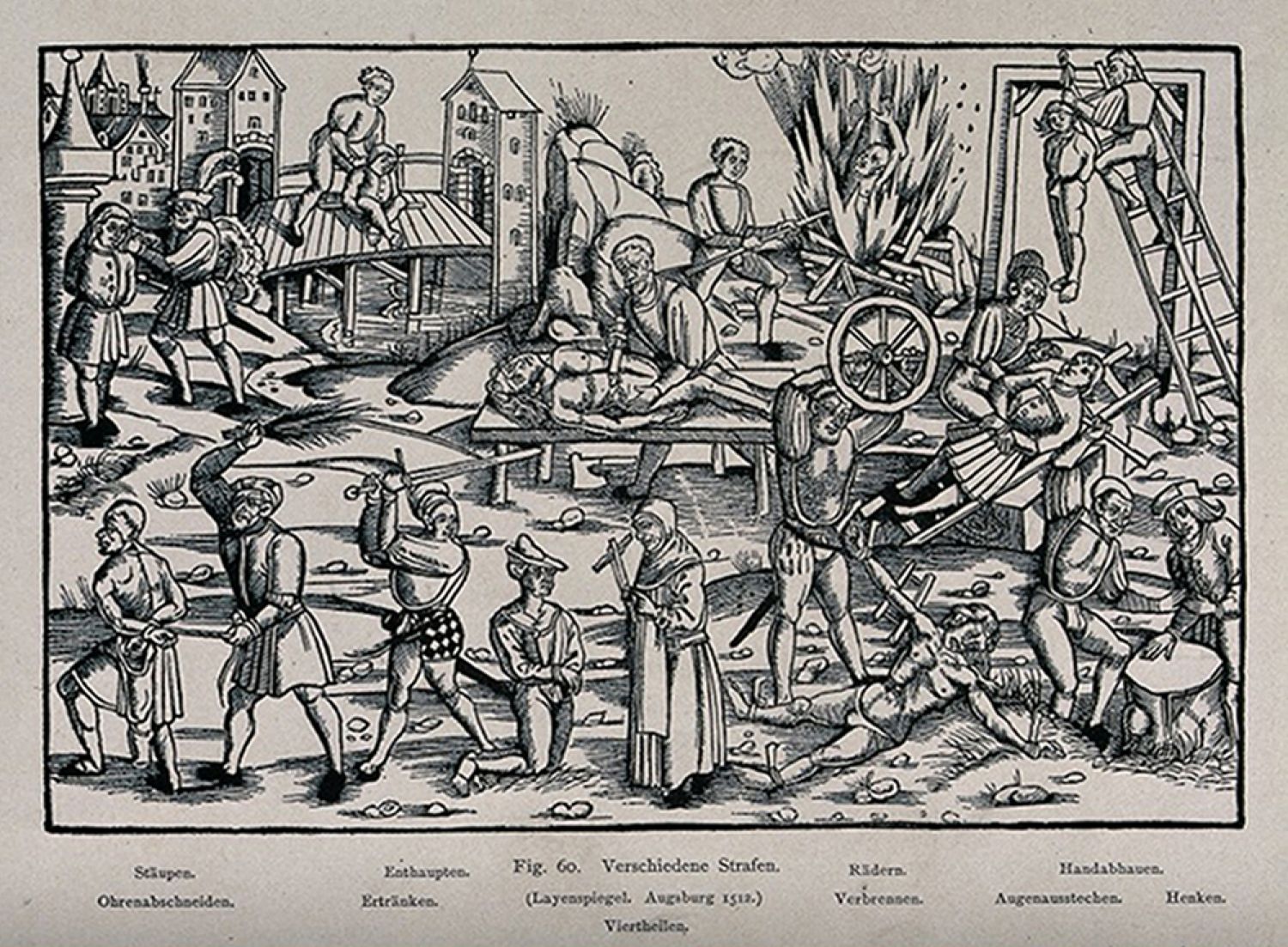

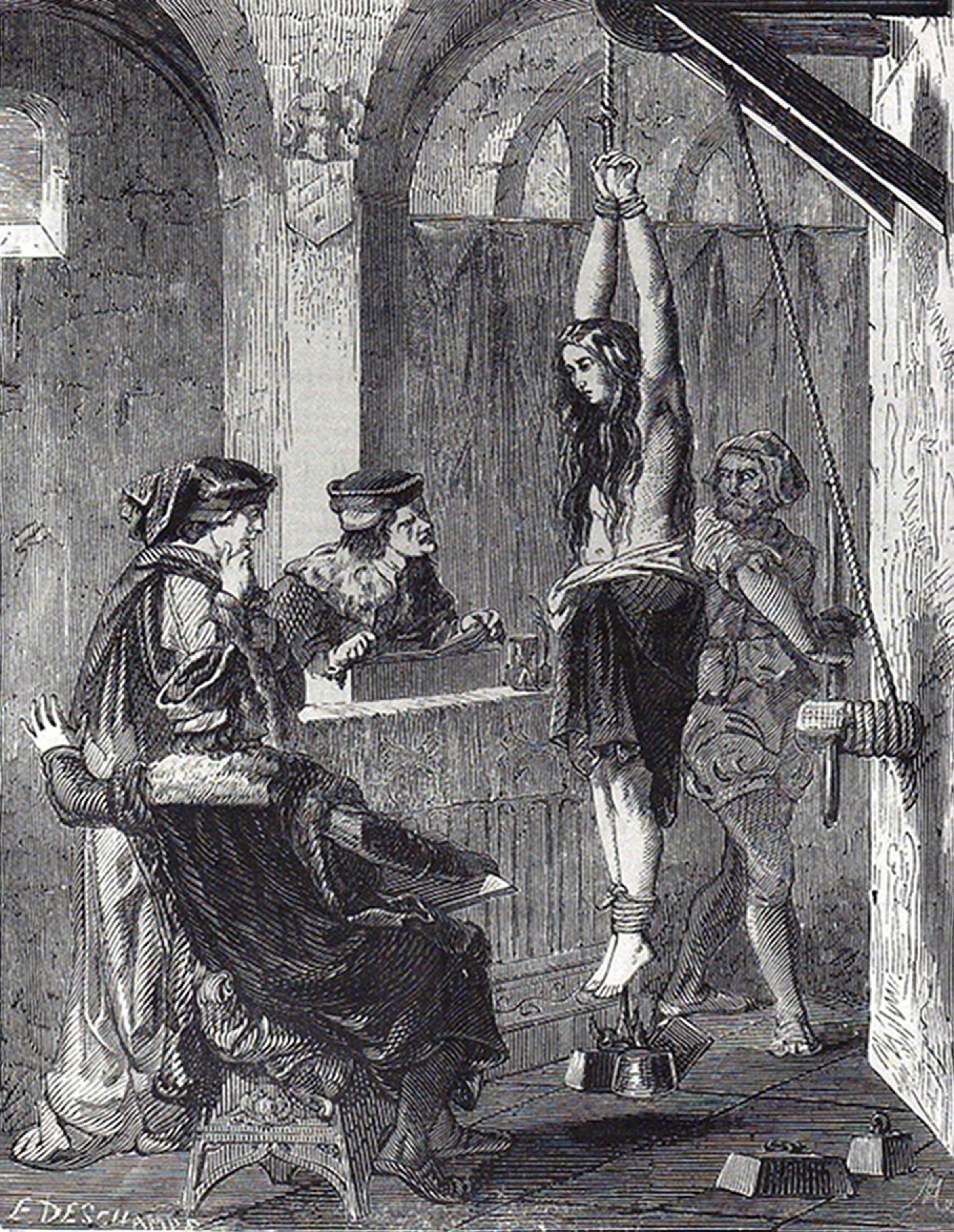

The images of witches in the attic are also indications from the point of view of the film about the «suspicious reading» that we should do of the therapist’s discourse about the madness and wickedness of the researcher. I consider these references, apparently anachronistic, to be another Brechtian contribution in Antichrist. The resource, called by Brecht «historicization»[5], consists in making history invade the narrative linearity and problematize the diegetic temporality, contributing thus to the production of the ultimate meaning of the film. Let’s recall, then, that the male character, supported by the subjective camera, visits the attic and finds out several images of his wife's research on gynocide, primordially composed by women’s tortures and murders. He also discovers the researcher’s notebook with progressively illegible and deformed writing.

Illuminated by the light of the lamp carried by the therapist, the accumulation of documentary images that the film shows us ‒ made up of woodcuts, engravings, paintings and excerpts from pamphlets of the Early Modern Age ‒ resembles the stills, the frames of a film of «barbarisms» (Figures 5 and 6). Hence, Antichrist connects the media of the witch-hunt time ‒ when the newly created press was beginning to be used to create a collective imaginary of demonization of women ‒ to the role of the current media in fulfilling the same function of stereotyping and control of the female sex, exemplified by the cinema, mainly the horror one.

As for the notebook, the direct consequence of its discovery will be to serve as evidence for the incrimination of the researcher in the following scene, the one with the role-playing game in which he represents nature, and she is supposed to represent rational thinking. In this scene, the researcher affirms that the therapist should not underestimate Eden, for she had discovered something else in her research material. The dialogue goes on like this: «Researcher: If human nature is evil, then that goes as well... for the nature of...Therapist: Of the women? Female nature? Researcher: The nature of all the sisters. Women do not control their own bodies – Nature does. I have it in writing in my books»[6].

In this scene, whose dynamics of illumination relates the researcher to darkness while her husband is privileged by well-defined framing, an insert shot shows us documentary images of women as threatening witches, linked to the devil or in libidinous positions (Figure 7). In the last take of the scene, there is a full shot of the couple and the therapist is seen announcing that «he can’t work anymore now»[7]. In fact, what is possible to identify at the end of the scene is a whole work that is carried out by him in order to extract from the wife a «definitive confession» of her intrinsic evilness. Such «work» is supported by a «documentation» collected by the therapist that justifies the inquisitory process to which the researcher is subjected, as the notebook found immediately before this scene, the medical report of the child with damages in her feet and the photograph of their son with inverted shoes.

It is necessary, however, to notice the historicization resource in action and create a relationship with the images that invade the scene. These images show the malignant representation of women that contributed to the creation of a whole fantastic imaginary about the «sorceresses» and their «hideous crimes», something that permeated the collective unconscious of the witch-hunt period. As a matter of fact, authorities of the time, not only religious, collaborated with several kinds of unreal, fanciful «documentation» ‒ such as the influential Malleus Maleficarum handbook ‒ so that this barbarism succeeded and that the horrendous and absurd confessions extracted from women, usually under torture, could be taken as true.

Historicization of the witch-hunt

Attention is thus again demanded to the hasty conclusions about the tendentious narrative that the therapy has been assembling, as one should observe that he is the one who makes the affirmations about the evil female nature and the inferences that follow from it. Nevertheless, the fact that the assertion «women do not control their own bodies; nature does» is projected in the speech of the researcher constitutes one of the elements that make the film much more complex and interesting.

The uttered sentences, some of the fundaments of the patriarchal discourse that the therapist embodies, when placed in the mouth of the wife, serve the purpose of complicating the Manicheist reading of man-oppressor versus woman-victim. The distancing form of the film thus reproduces the contradictions of our society, stimulating, on the one hand, the perception that it is very convenient and recurrent for the perpetuators of veiled misogynistic practices to present the most horrendous antifeminist ideas as if produced by women. It also reveals that it is a fact of material life that many women reiterate the basis of their own oppression by reproducing (often in an unreflective way) sexist discourses and practices.

It is also significant that the discourse projected in the wife's speech concerning what defines the «evil nature» of woman ‒ their control by nature ‒ departs, paradoxically, not from her experience with nature, but from what she would have read in her books, that is, from elements of culture. The feminine internalization of the voice of patriarchy, which dictates what women are and what they desire, is thus again problematized in the work of Lars von Trier, as it had been in Breaking the Waves. Let us recall that, in this film, Bess performs the almost schizophrenic act of representing the voice of God directing her behaviour, something that led to her tragic end and to the miraculous redemption of her husband. As expressed also in the researcher’s speech, Eden, as a metaphor for the «paradisiacal» patriarchal world, should certainly not be underestimated. The fact that this sexist discourse is expressed in the researcher's words precisely when a role-playing exercise is proposed in which she acts as the positivist rational thinking strongly defended by the therapist throughout the film should also be carefully considered. The strategy, consequently, unveils the sinister mystifying and obscurantist basis of such «enlightened» thinking and its role in sustaining oppression practices.

What is brought to light by the accumulation of historical documents in the film, in this way, is not only the process of construction of the «evil» nature of woman, but how such process becomes exacerbated precisely in the Modern Age ‒ the therapist himself, we should recall, relates the sixteenth century to the research of his wife. Actually, contrary to what common sense suggests, the peak of the witch-hunt was not in the Middle Ages, but between 1550 and 1650, welcoming a great European intellectual flourishing and the birth of the rational world to which the investigation of the therapist in the attic, «illuminated» by a lamp, does not fail to allude.

It is not mere coincidence that the height of the witch-hunt occurred precisely during the great navigations, the resumption of slavery, and the dawn of the Age of Reason. In fact, there is a very important structural element that fosters all these processes: the birth of the capitalist mode of production. As pointed out by Silvia Federici in her work Caliban and the Witch, what happened in that period was a process of «primitive accumulation» of capital. At this particular time in Europe when there was a need for accumulation of land and also of «bodies» ‒ the proletariat's labour force ‒ the greatest number of witch trials also took place[8]. This allowed that an entire way of relating and living could be destroyed for the emergence of a new mode of capitalist social relations. In the author's words, «The witch-hunt, then, was a war against women; it was a concerted attempt to degrade them, demonize them and destroy their social power. At the same time, it was in the torture chambers and on the stakes on which the witches perished that the bourgeois ideals of womanhood and domesticity were forged»[9]. Along with the proletarian, the housewife also emerged and a radical division of what was proper to the masculine sphere ‒ the sphere of value ‒ and to the feminine one ‒ everything that does not generate value.

Therefore, the process of historicization of the witch-hunt carried out in Antichrist highlights, among other aspects, the importance of reading the film against the grain. The therapist's paranoid and persecutory discourse, embodying contemporary common sense views to demonize the sexuality and intellectuality of contemporary women, equals the unreal, fantastical discourses of religious and legal authorities, artists, scientists, and intellectuals of the Modern Age, who projected all the irrationality, insanity and cruelty of their doctrine onto the women that they demonized. Those women, like the researcher of the film, had to perish so that the social order based on a mystifying «reason» could be guaranteed.

It is thus quite significant that the fire in which the therapist burns the wife's body corresponds to the last association built by the film between the therapist and the realm of light, enlightenment, and illumination (Figure 10). Implicit in the image is the fact that the flames of reason that welcomed capitalism five centuries ago were the same flames that burned the bodies of countless people, mostly women, and which keep burning forms of socialization that prove resistant to the advances of capital. As Antichrist's point of view is the one that connects the early modern witch-hunt to the contemporaneity, laying bare the latent contents of this barbarism, comfortably hidden in the «Dark Ages» by common sense, the image also has the potential, then, to problematize the triumphalist and teleological reading of capitalism.

Consequently, the estranged reading proposed by the film, the ideological trap set in it and its process of historicization causes Antichrist’s final evaluation about the contemporaneity to take as perspective the unfinished history of gynocide in Western culture – a direct relation with the unfinished work of the researcher. Hence, the most horrendous and most disturbing elements in Antichrist are not the scenes of explicit mutilation, which led so many spectators to refuse to watch the film. The horror is, indeed, in the implications that the film addresses about the validity of capitalist patriarchy in the contemporary Western society, about the cultural and institutional means that attest and naturalize it, and about its influence, often quite subtle, over the psyche of individuals. Subtle enough to make one not perceive its materialization in the narrative perspective problematized by the film. Subtle enough to make one hardly notice how this narrative perspective, embodying the brutal actions of capitalist patriarchy, is legitimized by many of us.

Bibliography

BRECHT, Bertolt. (1967). «Zweiter Nachtrag zur Theorie des 'Messingkaufs'». Gesammelte Werke in 20 Bänden. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, v. 16.

BUNCH, Mads. (2012). «Castration Anxiety and Traumatic Encounters with the Real in the Works of August Strindberg and Lars von Trier», in WESTERSTAHL, Ann. (Ed.). The international Strindberg: new critical essays. Evanston, III: Northwestern University Press.

CHATMAN, Seymour. (1990). Coming to Terms: the Rhetoric of Narrative in Fiction and Film. Ithaca, NY: Cornell.

FEDERICI, Silvia. (2004). Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation. New York: Autonomedia,

FIGUIER, Louis. (1867-1891). Les Merveilles de la science ou description populaire des inventions modernes. Librairie Furne, Editeurs Jouvet et Cie, (6 volumes).

INSTITORIS (Kraemer), Heinrich; SPRENGER, Jakob; (1991). O martelo das feiticeiras (Malleus maleficarum). Introdução de Rose Marie Muraro, Prefácio de Carlos Byington; Tradução de Paulo Fróes. Rio de Janeiro: Rosa dos Tempos..

JAMESON, Fredric. (1999). O método Brecht. Trad. Maria S. Betti, revisão técnica Iná Camargo Costa. Petrópolis, RJ: Vozes.

ROSENFELD, Anatol. (2006). O teatro épico. 4ª ed. São Paulo: Perspectiva.

SOUZA, Evelise Guioto. (2007). Dogville, Filme e Crítica. Master Dissertation, University of São Paulo, São Paulo.

SZONDI, Peter. (2001). Teoria do drama moderno (1880-1950). Trad. Luís Sérgio Repa. São Paulo: Cosac & Naify Edições.

TENGLER, Ulrich. (1512). «Verschiedene Strafen», in Layenspiegel, Viertheilen, Augsburg.

TRIER, Lars von. (2010). Antichrist. Array, Irvington, N.Y., Criterion Collection, 108 min., 2 DVDs.

TRIER, Lars von. (2009). A set of rules: Interview with Lars von Trier (video). UOL Mais, São Paulo, 26 ago. 2009. http://mais.uol.com.br/view/a56q6zv70hwb/lars-von-trier-fala-sobre-o-filme-anticristo-04023564C0811366?types=A&.

XAVIER, Ismail. (1984). O discurso cinematográfico: a opacidade e a transparência. São Paulo: Paz e Terra.

ZIKA, Charles. (2007). The Appearance of Witchcraft: Print and Visual Culture in Sixteenth-Century Europe. London: Routledge.

Footnotes

- ^ TRIER, Lars von. (2009). A set of rules: Interview with Lars von Trier (video). UOL Mais, São Paulo, 26 ago. 2009. http://mais.uol.com.br/view/a56q6zv70hwb/lars-von-trier-fala-sobre-o-filme-anticristo-04023564C0811366?types=A&.

- ^ SOUZA, Evelise Guioto (2007). Dogville, Filme e Crítica. Master Dissertation, University of São Paulo, São Paulo, p. 10.

- ^ SZONDI, Peter (2001). Teoria do drama moderno (1880-1950). Trad. Luís Sérgio Repa. São Paulo: Cosac & Naify Edições, p. 55. Our translation.

- ^ TRIER, Lars von. (2010). Antichrist. Array, Irvington, N.Y., Criterion Collection, 108 min., 2 DVDs.

- ^ BRECHT, Bertolt. (1967). «Zweiter Nachtrag zur Theorie des 'Messingkaufs'». Gesammelte Werke in 20 Bänden. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, v. 16, p. 653.

- ^ TRIER, Lars von. (2010). Antichrist. Array, Irvington, N.Y., Criterion Collection, 108 min., 2 DVDs.

- ^ TRIER, Lars von. (2010). Antichrist. Array, Irvington, N.Y., Criterion Collection, 108 min., 2 DVDs.

- ^ FEDERICI, Silvia. (2004). Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation. New York: Autonomedia, p. 165.

- ^ FEDERICI, Silvia. (2004). Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation. New York: Autonomedia, p. 88.