#1 – Intermittence

Filipe Pinto[For the next three months, Wrong Wrong magazine will publish short essays and pieces that propose a reading of the world from/out of Nothingness]

I am sitting outside. Not a breeze stirs, not a blade of hay moves. The landscape has been transformed into a still life. When the cicada falls silent, the image thoroughly petrifies — it seems there’s been an electrical failure, says Gómez de la Serna. The transparent heat fills the air and drives away the birds that were here in the morning waking everyone up. The heat makes the atmosphere pasty — movements slow down as if in a liquid, or on the Moon. Nothing can be seen that is not already here; nothing appears or disappears — it is the definition of a pause, or of an image. Of course the grass and fingernails go on growing, hair too; the apparent movement of the Sun does not stop, and the shadows follow it, but none of this can be seen. There are movements that happen and are not seen — like these, very brief, very slow — and movements that do not happen but are seen, as when the train on the next track begins to roll and it seems that, although stationary, we finally accelerate.

There must be a speed limit — perhaps on the order of millimetres per second — for visibility, a threshold at minimal speed beyond which movement ceases to be perceptible to us. We can tell that a plant’s stem has grown overnight, but its discreet velocity makes it impossible for us to witness it directly. At the opposite extreme, maximum speed also renders the moving thing invisible — we do not see the bullet in its deadly trajectory; indeed, there are rifles that fire the bullet at a speed greater than that of sound, so that the victim hears the bang only after being hit. The ignominy is heightened by the apparent inversion of events — an arrival before a departure, an end before a beginning.

What we hear when we hear something is always the result of a journey, of a movement; it always comes from somewhere, unlike silence, which offers no direction. That is why, in sound, the origin is always a question; we turn our heads to see where it comes from — even the deaf look at the cat to understand the source of the rustle. The same does not happen with vision, with the image; we do not question the origin of the image of that mountain — it is simply there, in the distance.

The cicada has stopped, the vegetation is not moving, there are no birds in sight. Nothing can be seen beyond what is already here, I repeat. I notice and come upon this scene because I too am still — motionless and absorbed; it is the best way to perceive immobility, without suffering the inconveniences of parallax. I am also part of the still life.

When that cicada fell silent, I suddenly heard it again. With continuous sounds, we stop hearing them and only notice them again when they abruptly disappear. For a few seconds, we hear not the sound but its absence. We parked the car at night and when we return in the morning, the car is no longer there. When we look at that specific spot, we do not see the empty place; we see the absence of the car. The same happens when the cicada falls silent — for a few seconds we have access to a particular kind of silence, a full silence, one with meaning and substance, a silence without sound but in which we still hear the trace of the cicada’s noise. Our attention is directed towards a nothing, towards an absence, towards something that is not there, towards a void. When the cicada falls silent, a kind of inaudible echo of the original sound remains, which makes us notice what is no longer heard.

Intermittent sounds make use of this kind of non-empty silence. In intermittent sounds, the moments of absence — of silence — are part of the sound itself, as if silence were a kind of shadow cast by each sound. Intermittent sounds are perforated, eaten-away sounds, but not incomplete. After a sound, there is silence, as after a gesture, the there is a pose and a pause. The silences within an intermittent sound are exactly alike — just like the initial silence; the same is not true of the final silence, the exit silence, when the sound does not return. This final silence has a different character, which is why it made me hear the cicada again, precisely when there was no longer any sound. When you hear the ambulance siren stop suddenly, you are close to the event.

In intermittent sounds, each sound is surrounded by silence just as each silence is surrounded by sound — they are always ending and beginning again — and it is this interweaving that prefigures the tap on the shoulder. The alarm and the siren have this form — they wake us because otherwise we would quickly grow accustomed to a sound as continuous as a smell. Continuity anaesthetises and numbs. A baby’s cry is not continuous; it works through intermittence, it works because silence intervenes, it works because of successive nothings. The intermittent counters the flatness of things. What calls to us is both the sound and the silences — it is their congenital conjunction; the intervals must be measured, they should consist of roughly the same amount of matter (sound) and void (silence); if these intervals widen too much, intermittence is lost and the sound changes dramatically in character.

In winter, the deciduous tree is emptied out, left only with what it is; like a skeleton, it comes to occupy only its own space, like the instantaneous image of an arrow, which occupies only its own space and therefore also appears static. In an accelerated recording, these trees are intermittent, with a very slow pulse of lushness and scarcity, lushness and scarcity, lushness and… Intermittence has this arboreal, seasonal character.

Intermittent like all living hearts, or intermittent like a cogwheel, a comb, a railing, a balustrade. Intermittence means difference and repetition within a system, within a pattern. Intermittent like a heartbeat, intermittent like speech; intermittent like the pedestrian crossing, which is itself also a switch.

In a book written in 1995, Jean Baudrillard proposed a kind of intermittent architecture — an architecture as a provisional occupation of space; instead of haughty and perennial, altruistic and volatile. In that text, Baudrillard argued that new buildings should include, in their pillars, the holes for the explosives required for a future implosion. The construction would facilitate its own obliteration from the outset; the occupied space would be converted into a merely provisional, transient, temporary space — intermittent, therefore.

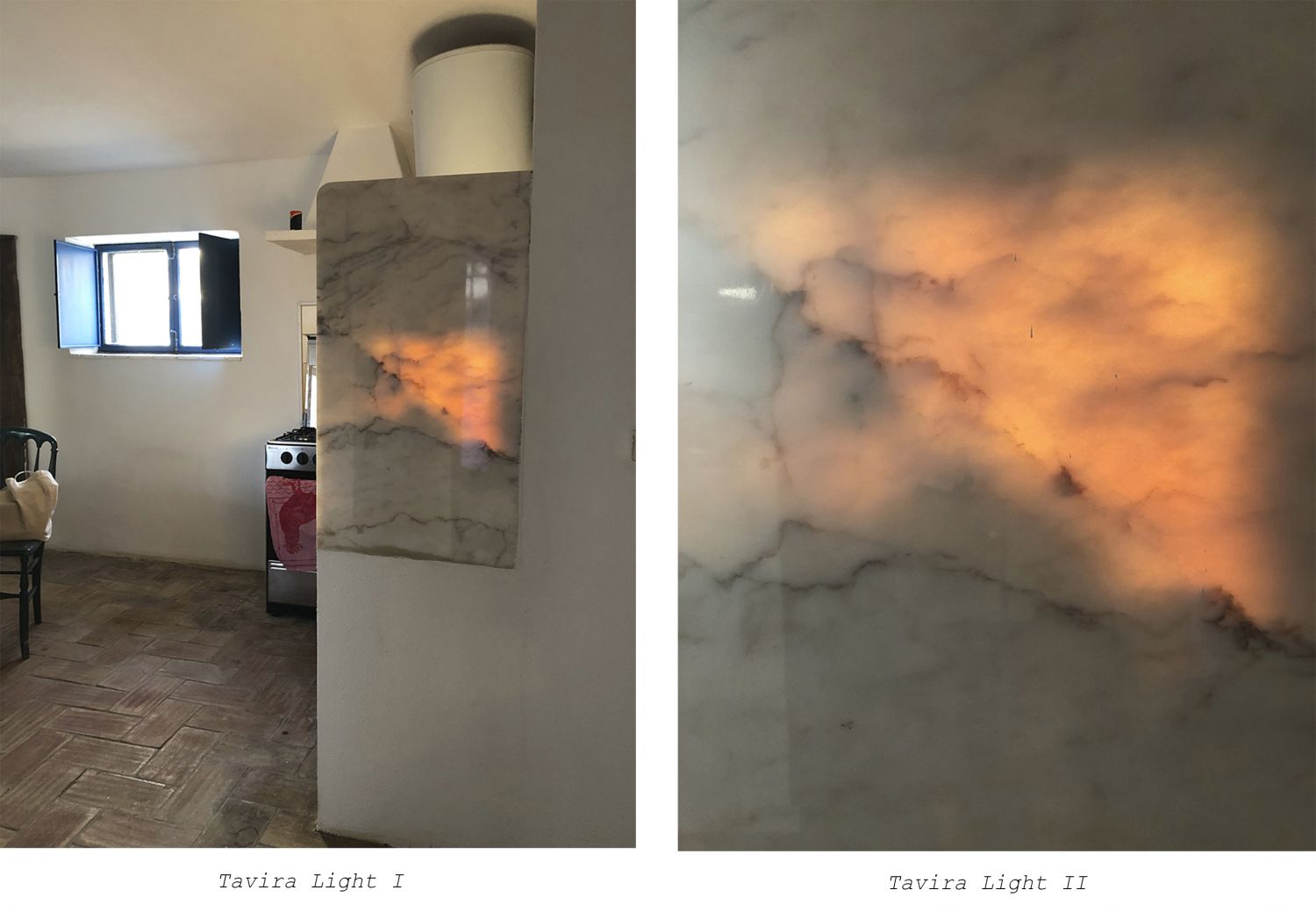

I go back into the house, and in the kitchen I see the marble lit from behind. Those rays of sunlight travelled 150 million kilometres in about eight minutes at maximum speed without hitting anything; that beam of light threaded its way through planets and moons, clouds of gas, asteroids, etc., to fall precisely into the narrow opening that was that tiny window, finally coming to rest on the slab of pink marble that hid the sink from the eyes of those coming from the street. At eight p.m., the light is already raking, and to reach this spot, now through the atmosphere, it also veered around trees and hills, walls and huts. In fact, from the confines of the solar system to that kitchen window nestled on a ground floor in the middle of nowhere, nothing came between the Sun and the translucent slab of marble. From this side, I perceived that travelled light piercing the porous stone — sponge stone, foam stone, intermittent stone.

[Next text: Silence]