The image that pierces us

Horácio Boavida

Let us talk about images.

An image must be seen. More than being seen, an image must be able to look at us. If it cannot be seen, if it doesn’t look at us, if it parades before us like the blind whirlwind of images that haunt our daily lives today, it’s because it’s not truly an image. And those that never become images, they’re not worth talking about.

The history of the image is, therefore, the history of the image attempting to break away from itself.

It is naïve to believe in the single screen, as in the single canvas or single sheet. As we said, an image, to be an image, must be seen. It needs a viewer. The viewer is the off-screen element of the image, its first double (there are others, because the double, as we shall see, is always a multiple). A frequent mistake is to consider the viewer as a subject extrinsic to the image. There’s a vector that pierces both which goes from the viewer to the image and from the image to the viewer and from the image to another image and from the viewer to another viewer and from the image to the world and from the world to the image and from the viewer to the world and from the world to the viewer (etc., etc., etc.).

Someone once said that a certain Constable landscape referred less to the actual landscape it depicted than to another landscape painted by the artist. By this logic, an image may thus refer more to another image than to its actual object. The image explodes in several directions and it is impossible to chain it to its referent, whatever that may be (in other words: it is impossible to predict the direction and speed of the vector triggered by an image).

On that one screen – or on that one canvas – there is therefore no single delimited or circumscribed image, but rather a cascade of images – both absent and present, both real and unreal. This flow of images thus constitutes the unlimited power of the imaginary. No image exists in isolation from the world, that is, cut off from the flow of images that constitutes the multiplicity of the world. Cutting out, assigning a limit, is merely the gesture that actualises an image from among the unlimited virtuality of all the images that can possibly be imagined.

Ethics – but also aesthetics, as the two are inseparable – reside, one and the other, and in relation to the image, in the possibility of creating a form, that is, in the possibility of articulating and delimiting a set of formal aspects (colour, line, shadow, texture, and others) which are worked on through the use of a set of techniques/devices (perspective, trompe-l'oeil, sequence shot, parallel montage, etc.) and instruments (a brush, a camera), handled by someone (a person?) or something (a machine?) thus producing a piece of reality that didn’t exist before. An image is never merely representative, and even the most concrete figuration produces a new abstraction of reality (put simply: any image produces a real, regardless of its referent or object, giving rise to something new). Form is what distinguishes one image from another and connects an image to the world. «Ethics is always aesthetics, because truth is always beautiful», Tarkovsky once said. And, as we well know, there are images that are fair and beautiful and others that, on the contrary, are not. After all, not all images are valid, not all images interest us: ‘a tracking shot is a moral question’, said Godard, following Rivette.

But the fact that there are images that are not fair nor beautiful doesn’t mean that their lack of fairness or beauty is the result of a problem of restraint, delimitation or unity (unity of the image, unity of the screen, it matters little). For around any image, fair or unfair, beautiful or un-beautiful, hover all the others, flying overhead.

The uniformity of the canvas, the screen, the sheet of paper is strictly illusory. As we said, Constable's landscape refers first and foremost to another landscape by the same painter, but also, of course, to many other images – and it is in this cascading flow that lies the essence of the image (its imagery, so to speak). And since we are talking about imagination, let us imagine, as an exercise, that we are watching a film in a dark cinema and that, even if only for a few seconds, we involuntarily close our eyes. It would be wrong to assume that, in that brief moment when we closed our eyes, we saw fewer images than the other viewers sitting next to us who have kept their eyes open. For the images we dreamed of, during those brief seconds when, theoretically, we would have seen nothing, matter as much as the clear and objective images of the film (and perhaps one would not exist without the other). Any image necessarily refers to another image. The images from outside refer to the images from within. And no image stands alone in this world.

The viewer does not confront the image as one, just as one does not confront oneself as a single entity (or as a one). One confronts the multiplicity of the image; one confronts oneself as multiplicity. And between the viewer and the image hover, flying overhead, all other multiplicities: history, desire, culture, the gaze, death.

This doesn’t mean, of course, that some images have sought, more than others, to stabilise themselves in space and time as uniform or homogeneous models, reproducing themselves like industrial products on an assembly line or like commodities in circulation with their abstract value. That images are a flow doesn’t mean that this flow is not diverse: hallucinatory becomings coexist with manufactured clichés.

«On the contrary, modern painting is invaded and besieged by photographs and cliches that are already lodged on the canvas before the painter even begins to work. In fact, it would be a mistake to think that the painter works on a white and virgin surface. The entire surface is already invested virtually with all kinds of cliches, which the painter will have to break with.»[1]

The multiplicity of images takes over the screen even before we add to it any form. As Deleuze says, the very emptiness of the screen is itself an image, thousands of images fighting each other, competing for the place of that emptiness. The struggle against cliché is the struggle against the already seen, against déjà vu, the struggle for right images, for the rightful becoming of images. It is important to break with these images that impose repetition and give shape to the difference of the images to come.

The viewer confronts the image and in this confrontation an abstraction is produced. The image appears to him as a thing, cut out from its surroundings. A frame, a line, an outline, there is something that separates the image from the rest. But where does this separation come from? Is it specific to the image? Or is it not, above all, a product of language and the play of signifiers? After all, objects – and, for that matter, subjects – also appear to us as one: a table, a door, a house, a person, me, you, us and others (even subjects and objects that exist in their plurality are, in a way, one, as they constitute a single category of things). What cuts through reality – including that piece of reality that we define by convention as sensible, perceptual or visual – is the effect of the signifier. It is the signifier that creates homogeneous differences and unary distinctions within the unlimited flow of things, abstracting and separating objects from one another and, of course, subtracting unity from multiplicity.

We may fall into the illusion that reality itself already exists separately a priori, that objects exist in themselves and not as a relation, and that it is colours or shapes – or any other “intrinsic” characteristic – that allow us to distinguish one from the other. But ultimately, even colour and shape depend on relationships of meaning. For even liquid and gaseous flows, with no defined colours or shapes (which, for that very reason, would unlikely be perceived as unitary), are abstracted and separated as units by the functional and objectifying power of signs: the sea, the river, the cloud.

Hence the importance of poetic ambivalence in the logic of meaning: instead of sea, we can say blue, calm, sky, God, and even earth, infinity, or death. It is in the metamorphic and stylistic play of poetry (metaphors, hyperboles, oxymorons, contrasts) that we open up meaning to the multiplicity of reality: that we make the signifier, each time, double, multiple and infinite, unchaining it for a few moments from the forced slavery imposed on it by the illusory weight of the referent.

Images, however, do not exist outside a specific set of meanings that are both cultural and contingent. In Greek, an image was called an eidolon, and idol meant “double”. Doubles were ghosts, dreams, shadows, and hallucinations[2]. Thus, the image acquires, at its root, a ghostly resonance: it has the power to duplicate, and the double is understood as a spectre, simultaneously alive and dead, present and absent, real and unreal.

The image has never been unitary. The Greeks already knew this, so much so that they associated the image with the double, duplicity and the number two. In fact, for a long time, the number two dominated the Western conception of the image (thus systematically exceeding the figure of unity). If the image is the double of the object, then the image can never be one, that is, perfectly delimited or cut out from the world, because the image, as a number 2, will always depend on its number 1 – the object, the referent, the real – without which it would simply not exist.

According to the perspectivist model of the 15th century, images and the imaginary become scientifically and objectively anchored in the weight of the referent and reality. The Renaissance window thus implies a reflective unfolding of reality in the image, an objectified spatial continuity (or continuum[3]), regulated in turn by mathematical proportions capable of guaranteeing the reliability of the representation (or, in other words: the exact duplication of the object).

Two theoretical hypotheses regarding the implications of perspective:

1) either the image represents and duplicates reality and, in this sense, as a duplication, it must be expressed by the number two (at this level of analysis, it matters little whether consciousness/imagination takes precedence over the object/reality, or vice versa, since the consequence of either proposition is that the separation is never absolute: there is always something that is reflected from the object to the image or projected from the image to the object);

2) or the image is produced as a de facto continuity of the real and, as such, both the image and the real would be subsumed by the figure of the number one (in any case, and in view of this hypothesis, it is not the image that is one and separate or delimited from the world, but the image and the world themselves are one and continuous with each other).

We know that the “modernity” that developed in the 16th-18th centuries, and which has perspective as its starting point, progressively established an increasingly fierce separation between the subject (or consciousness/imagination) and the object (or reality). But this separation (Cartesian, dualistic, sometimes dialectical) has continued to produce a series of theoretical difficulties that modern European philosophy has attempted, without much success, to resolve, according to various conjectures, some more idealistic, others more materialistic: is material reality merely a duplication of the structures of consciousness? Does matter exist, in fact and objectively, beyond consciousness? Or, on the contrary, does matter ontologically precede consciousness (in which case consciousness is “secondary”)? And further: is consciousness merely a deformation or mystification of reality, having no reality of its own? (Of course, all these questions are unanswerable, as they depend, first and foremost, on the “artificial” and programmatic division between subject and object, between consciousness and matter, or between image and reality).

What interests us in this essay is that, even imposing this a priori separation, it has never been possible to completely annihilate the existence of a relationship between the subject and the object or between image and reality. Even Descartes, who proclaims with absolute certainty the absolute separation of the two substances (res cogitans, consciousness, and res extensa, matter), never ceases to reconnect the two, for even he senses that there must necessarily be some relationship between them (he wrestles, for example, in his Meditations, with the problem of pain[4]). Thus, even in the separate world of the Cartesian subject, solitary and disembodied, it is always the figure of the double that is established (this doubling implies that, even assuming the difference between substances, there is some continuity or ‘interaction’ between them, which ultimately invalidates the project of total dualism – and separation).

This explains the interest of Renaissance painting in representing ‘external reality’, because better than any other, it can be translated as a geometric and mathematical structure, thus objectifying the real and duplicating the structures of consciousness in matter (the subject-object separation is always hierarchical and, according to idealistic philosophies, implies the subordination of the objective and material world to consciousness). If the subject/consciousness is a superior reality defined by the capacity to think (Descartes), objective reality (which submits to this subject) must, in turn, reflect the mathematical regularities of reason (it is in this ability for the reflection of two distinct realities – which thus become, in a way, equivalent – that the faculty of representation is discovered). Renaissance perspective of the 15th century thus foreshadows 17th century Cartesian rationalism, marking a first epistemological break and inaugurating a hitherto unprecedented way of objectifying reality.

«The painter, in fact, strives to represent only things that are visible under light.»[5]

According to the first theorist of perspective, the only thing that interests the painter is what lies outside him: res extensa, matter or objects that can be represented as concrete and factual externalities (once again, we can clearly understand the fascination of perspective painting with so-called “objective” reality: we can represent or duplicate a table ipsis verbis, but how can we duplicate an abstract idea or a feeling such as hatred and envy?). The fundamental difference between the Greek concept of the idol and Renaissance perspective is clear: if, on the one hand, the eidolon is conceived as a hallucinatory and phantasmal duplication (a duplication which, however, is neither real nor unreal, as it is not based on any rationalist division of substances), on the other hand, perspective is founded on the sign of a supposedly objective, regular and mathematical representation of the world (a material world that, in fact, only acquires a necessary realness when subjected to consciousness and reason). In fact, both categories presuppose the image as double, but pointing in totally different directions: the first establishes a principle of hallucination, the second a principle of reality. What interests us is that here too, in the "modern" conception of Western representation, the image has the function of duplicating the real, thus making it impossible to assert that circumscription by the frame performs the exact function of confining or limiting the image itself. On the contrary, the cropping of the image (its limit) is precisely the device that ensures the illusory effectiveness of perspective as a game of continuity between the real and consciousness (it’s in the same movement in which the image is separated from the real that it becomes capable of duplicating it). And it is precisely through this separation/continuity that the viewer is induced to dive into the boundless depths of the image. Perspective is just that: a false boundary, a game of tension that is staged by the spatial delimitation of a depth that is, in fact, unlimited. When we look at a landscape (be it real or imagined) in which it is possible to see, in infinity, the horizon line, the unary temptation of meaning is momentarily abolished by the power of the unlimited, and suddenly, all things become disoriented in a dizzying whirl.

For Kant, the distinction between the beautiful and the sublime lay precisely in this point: the beautiful implied the delimitation of a specific form; and the sublime, on the contrary, the absence of limits and fixed forms[6] (for example, an earthquake – the dynamic sublime – or the vastness of the desert – the mathematical sublime). Renaissance perspective (even though it foreshadowed the objective, reifying and, in a way, totalitarian dimension of Western rationalism) still gave rise to a sublime desire to break through the very limits of the image (and, therefore, with the image itself as an objectified totality and, for that very reason, an enclosed one). Three-dimensionality thus founded not only the explicit desire to objectify and enclose, but also the tacit and dizzying desire to expand the image as a “flat and contained thing”, precisely because the image was not understood only as an image (or separation), but above all as an extension of reality. It was then, in this virtually infinite and unconstrained extension, that arose the sublime desire to expand not only the image, but also the image as a double of reality (which ultimately implies the desire to expand reality itself). Herein lies the paradox: perspective begins as a duplication of the real (and therefore as the production of an identity), but this very process of duplication (i.e., the creation of an-other) inevitably ends up establishing its vanishing point (and therefore the production of a difference). In fact, the Double is never exactly the same as the Same it seeks to duplicate. The Double is always, and necessarily, a becoming (if Renaissance perspective interests us much more than Cartesian rationalism, it’s precisely because in the vertigo of its depth we find some desire for the sublime – therefore, for the unrepresentable – which is absent from the projects of Cartesian geometry and mathematics of a total and abstract equivalence between consciousness and the real).

Now, a world that is composed of becomings rather than substances cannot be defined as one or unary. And if the world is not one, there’s more than one way of representing it (perspective was not, therefore, a truly objective technique, contrary to the realist doxa that sought to objectify it once and for all, thus turning it into a sacrosanct and absolute model of the teleology – or theology – of representation). As we well know today, perspective was nothing more than one among many symbolic and conventional forms (Panofsky's thesis[7]), another way of representing reality, bringing out a difference, a becoming and, possibly, a hallucination (the most marvellous incongruity of perspective lies precisely here: that it is capable of causing hallucinations, when its entire theoretical intent was precisely the opposite, that of regularising, objectifying, making real). The Renaissance window was, in this sense, contradictory, as are all windows: simultaneously a defined cut-out and boundless depth; a mathematical chain of planes and a sublime vanishing point; containment of the image in the frame and a vertiginous desire to let ourselves be swallowed up.

The Baroque went far beyond the “realistic” ambitions of the Renaissance, perfecting itself as the art of illusions, in an ever-increasing divergence from reality. The desire for vertigo, which already potentially existed in the vanishing point of Renaissance perspective as a possibility for the unlimited expansion of reality, deepened (and improved) more and more, manifesting, in successive deconstructions, the pleasure of illusion in all its splendour: the impossible oxymorons, the deceptive anamorphoses, the mirrors of Versailles and, of course, the vertigo of trompe-l'oeil. We do not intend to outline a history of the image in this essay, but there’s no avoiding this painting by Rembrandt:

Unlike Renaissance perspective, which based its legitimacy on its objective representation of reality, the Baroque was founded on the pleasure of illusion itself, revealing its devices and techniques as tricks and artifices, in a game of mise en abyme that would ultimately prefigure, centuries earlier, the modernisms and ruptures of the 20th century (this painting by Rembrandt prefigures Brecht, Pirandello, Godard, Cocteau and so many others).

We must admit that we only see an image when that image “pierces”[8] us, when «everyone suddenly feels looked at».[9] In a way, the exuberance of the Baroque has to do with this: not only the pleasure of looking and its deceptions, but above all the pleasure of the vertigo we all feel when we realise that images also look at us. Images pierce us, break out of their frames and their limits, extend into the abyss of reality, towards the sky and God (instead of reality extending into the image, as in the Renaissance, it is now the image that breaks out of its frame and, like an arrow, pierces reality). Baroque images are like phantasmagorias that invade the world of the living, illusions that not only reveal themselves as illusions, but show us – if we don’t know already – that the world itself is the greatest illusion of all (Baroque, in its theology of excess and opulence, makes the Cartesian principle of reality hallucinate). There is no possible unity, no limit that cannot be exceeded – the vertigo is total.

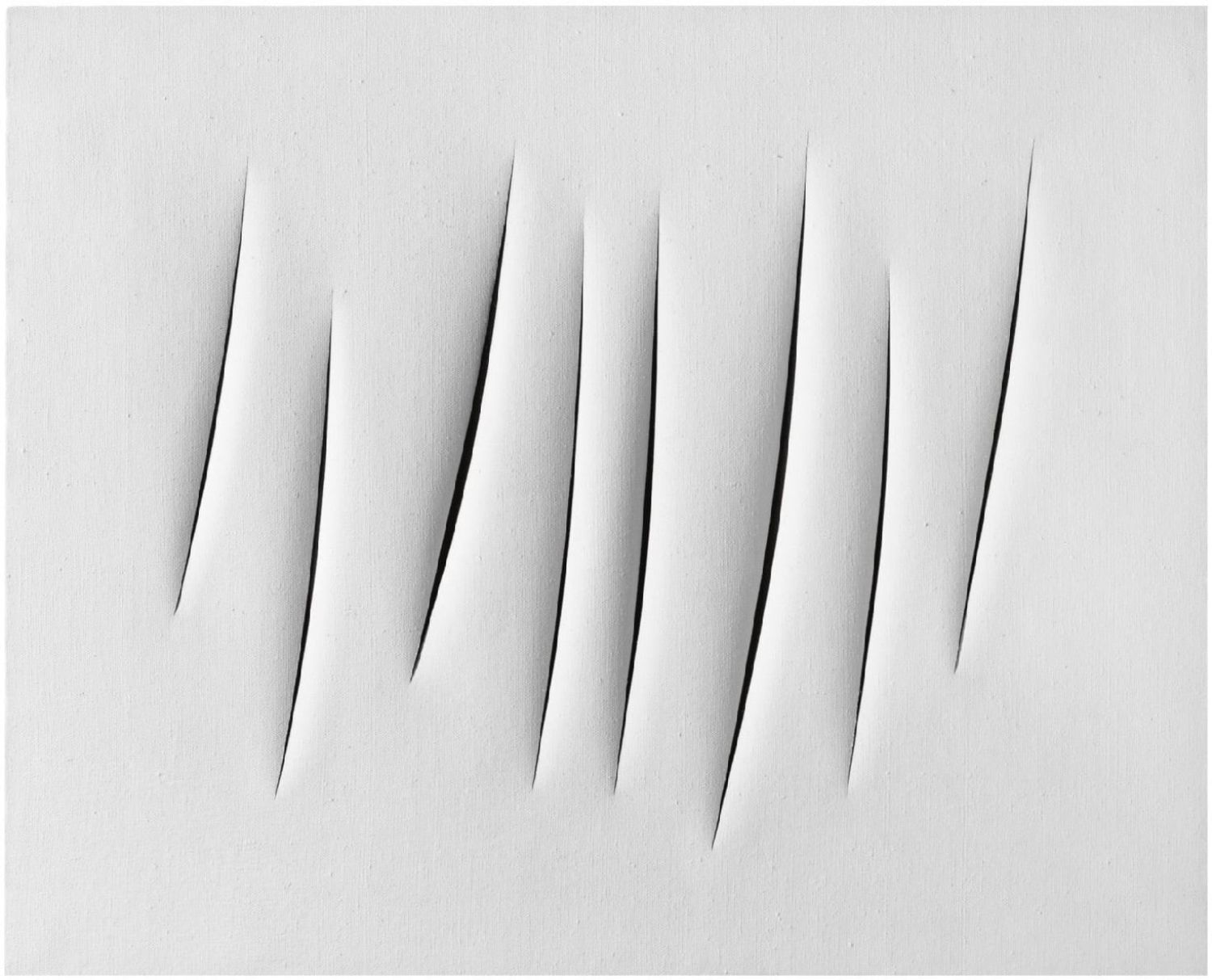

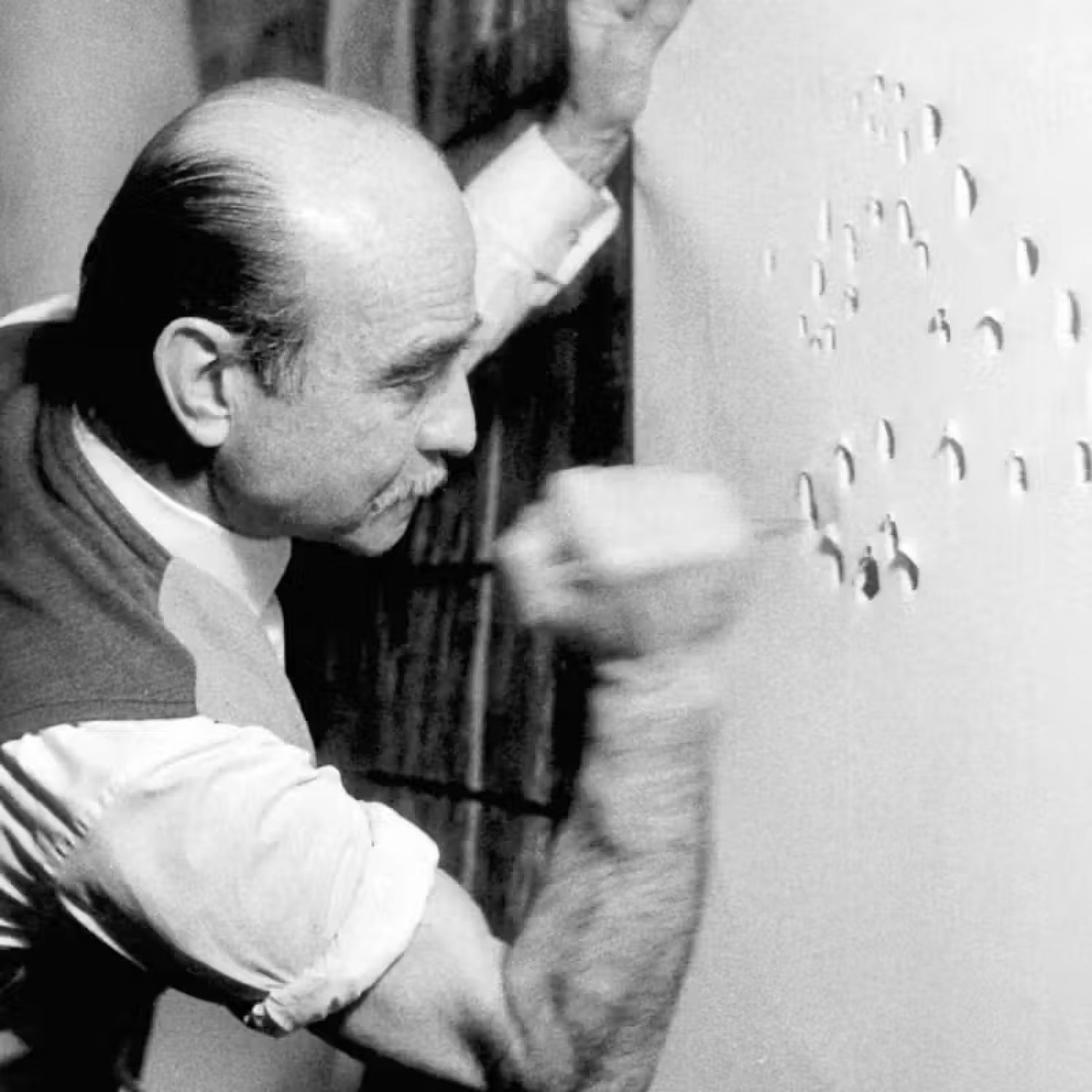

At the end of the 19th and throughout the 20th century, images became increasingly fragmented, shattered, multiplied: from impressionism to pointillism, through Kandinsky's musical compositions or Fontana's spatial paintings. It’s no longer enough for an image to refer the viewer to the multiplicity of images in the world: this multiplicity must be imposed on the concreteness of the image, the very “substance” of the image must be fragmented, the image itself must become a thousand distinct images. There are even those who burn their paintings (Yves Klein), so that the image is also matter, and those who tear their canvases (Fontana), so that the infinite beyond the image can be seen.

And if it is true that Lucio Fontana's Spatial Concept canvases are largely a reaction against the legacy of perspective, symbolizing a cut in the three-dimensionality of space which guarantees the effectiveness of the mimetic device, the truth is that desire for depth — and for penetration—persists (instead of depth within the image, depth outside the image). Thus, in Fontana's “paintings”, it’s the image itself that is abolished, or at least the image in its traditional sense, as a duplication or even multiplication of reality. In this regime, the image is no longer substantiated or grounded in anything; it is now its own piercing, that is, the movement that is capable of cutting through both the image and reality (for it is the very distinction between the two that is torn apart in a single stroke). In fact, in Fontana's works there’s no longer a double (the image as representation) or a multiple (the image as fragmentation, as a plurality of images), but all the power of abstraction of the infinite (the image as a cut, as pure piercing; the image is no longer what’s outside, nor inside, it's not even the multiplication of sides, but the very movement of piercing of all realities, limits and constraints).

As with Fontana, the history of the image is the history of the image transcending itself, breaking its own limits, mocking the unary and homogeneous meanings of the world, bursting as an “object” that one would want to be circumscribed and total. The fact that not all images follow this destiny, that many confine themselves to their role as commonplaces and clichés (Deleuze), dominated by the market and spectacle, by narcissism and voyeurism, doesn’t mean that the image's revolutionary trajectory is not defined by transcendence and excess or by the exorbitant surpassing of itself and of reality.

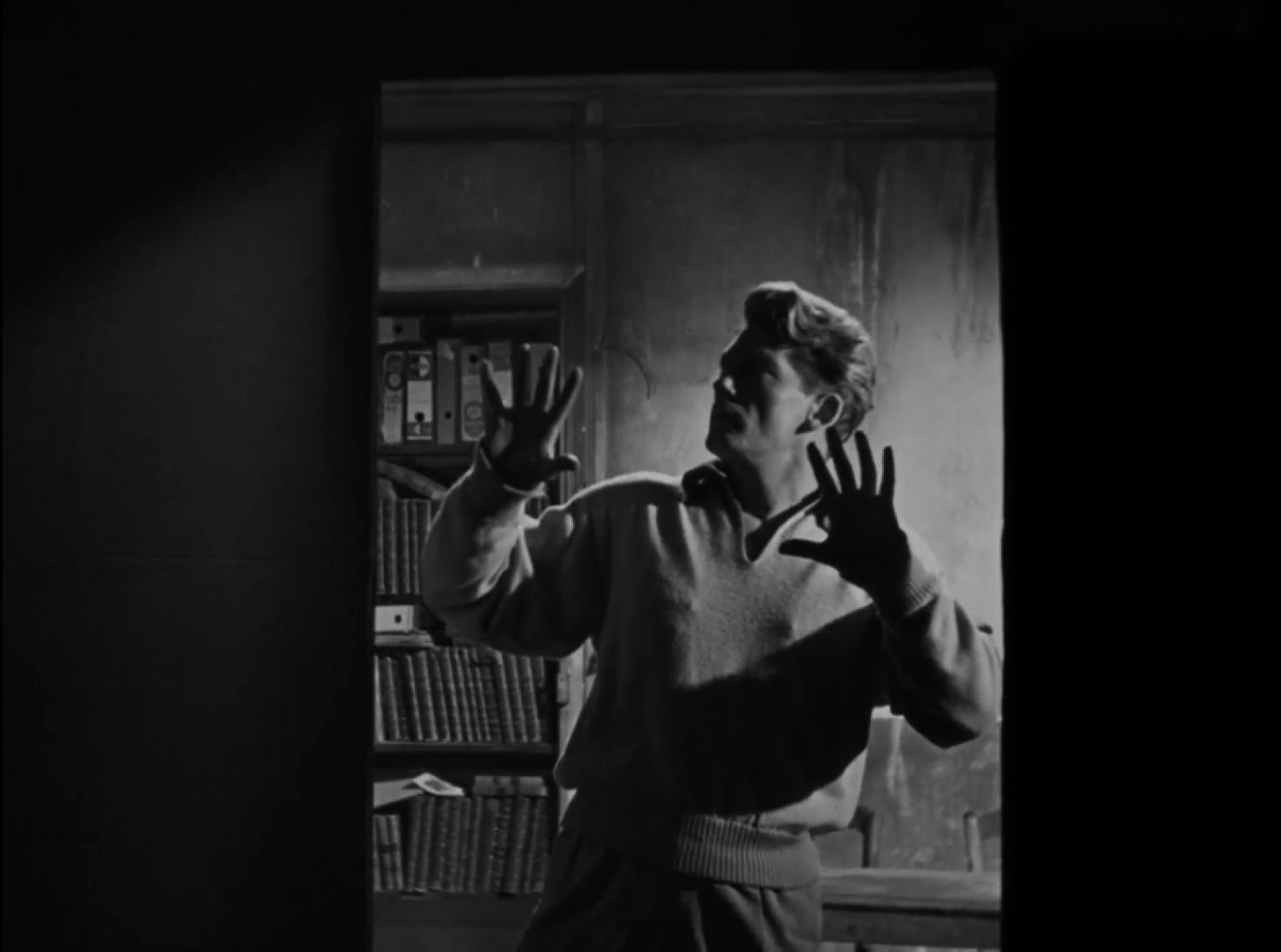

This is the case in one of the great films about the image as a crossing point – Orpheus, from 1950 – in which Jean Cocteau inventively updates the famous Greek myth for the existentialist Paris of the 1950s. In this poetic film about the world of the living and the dead, mirrors are one of the elements that allow the crossing between the two worlds. On the other side of the mirror and on the other side of the image lies the world of the dead, of doubles, of eidolons (ghosts, shadows and hallucinations). Here, the crossing is reversed: it is the image that is transfixed by the subject, in a kind of negative of Rembrandt's painting (there, the girl was trying to escape through the frame; here, Orpheus literally enters the image). But Orpheus's piercing the image rhymes not only with the mise en abyme or trompe-l'oeil of the Baroque, but also with Renaissance perspective desire for depth (hence, for continuity between the image and reality), or the desire for infinity beyond the image, reflected in the piercings of Lucio Fontana's canvases (here, Orpheus' fingers pierce the liquid matter of the mirrors that allow passage to the Hades). Whether in the form of duplicity, multiplicity or infinity, the question is always that of an increasingly profound penetration of reality and of the image itself (and of all the unary conceptions that seek to delimit one and the other).

Herein lies our bet: perhaps a unified and uniform image, flattened and restrained, is simply nothing more than a ‘bad image’ – an uninteresting painting, an uninspired drawing, a film like any other. Objects that are increasingly confused with reality itself, purged of their imaginative power (that is, of duplication, multiplication or infinity).

These are the images that proliferate today. Baudrillard called them simulacra: billboards, advertisements, pornography, reality shows, television news, live television broadcasts, video calls and, of course, the increasingly irrelevant art of our time – images that only refer back to themselves (are they even images anymore?).

A bad image is therefore an image incapable of transcending the limits imposed by the screen or any other form of confinement and separation. Because, ultimately, every image that matters – from Greece to the Baroque, to the cinema of Cocteau and Godard – is one that is capable of exceeding its own “orbit”, its own limits. There is no image, strictly speaking, that does not duplicate or multiply reality. There is no image that does not impose an exorbitance, a phantasmagoria, a hallucination (even a poor “object” is better than no object at all). There’s no image that does not overflow reality. What’s left are not images, but soulless repetitions of reality: commodities, simulacra, clichés, the submission of the world to a formula of market and domination. Here we find the standardisation of the world, not because of screens or the material and formal confines of the image, but because the images themselves have become incapable of overflowing them, of suddenly interrupting the continuity of the millennial and disruptive game of art – the game of the image as excess and as piercing. An image that doesn’t overflow is an image that no longer refers to another image: it’s a lonely and sad image, it’s a dismembered and separated image that is no longer capable of connecting to the world – it’s an image without imagination.

Fragmentation in itself offers no salvation. Is there anything more fragmented than the logic of television zapping or Internet multibrowsing? And what salvation comes from that? Modernisms (for example, in cinema) were constituted both as experiences of hyper-continuity and hyper-fragmentation, and there were even those who oscillated between the two, dancing between the sequence shot and the jump cut (for example, Godard). Both fragmentation and continuity overcome linearity, because what matters most is that images are capable of overflowing (the continuous is not necessarily linear, because, like the fragment, it is also an excess). Precisely, Godard's or Béla Tarr's sequence shots exceed all possible linearity, as they abandon cause and effect and give shape to the absolute vertigo of duration – of both space and time.

It is also important to state the following: concepts are never purely abstract or scholastic, and, ultimately, to think means just this: being able to change concepts according to their actual application (let us stop trying to save the dialectic that opposes the positive to the negative, or good to bad, or the continuous to the fragmented – dialectics, today, serves no purpose). Now, fragmentation, no longer in the hands of Godard, but of Capital, involves the systematic bombardment of attention and the capture of the imagination through constant excitement, as well as the repetition of hollow and empty formulas. The fragmentation taking place on the TV screen or computer screen already exists subordinated to consumer economy or the technical operability of control panels (the screen is now a console, a data centre, a terminal to which the subject connects and which allows not only to command, but also to be commanded).

In fact, multiplicity in Deleuze and Guattari is composed of both cuts and flows/continuities (as in the Greek concept of hylê[10], or matter), and at no point in the Anti-Oedipus is fragmentation presented as something positive and absolute.

“Every machine, in the first place, is related to a continual material flow (hyle) that it cuts into.”[11]

“Desire constantly couples continuous flows and partial objects that are by nature fragmentary and fragmented.”[12]

If fragments existed completely separate from one another, the world would be totally disjointed. Every fragment needs a flow that connects it to another fragment, just as every flow needs to be fragmented in order to transform into something else. The flows of images in capitalism are incessantly cut, even carved up (zapping, advertising), and therefore no possibility of meaning emanates from them anymore. They are images without time or presence, without otherness or imagination, totally disconnected from one another (superficially, they seem to constitute a flow, like an Instagram feed or a sequence of images on the television news, but a closer look reveals that this flow has no depth, as it is composed of a thousand and one fragments incapable of connecting with one another). Precisely, today's images are the most totalitarian manifestation of a fragmented order that no longer connects anything. Such images are defined by total transparency and linearity (absolute coincidence between the image and reality, according to the logic of the hyper-real, of simulacra, of visibility and exposure, of control, communication and operational commands) and it is against this that we must fight. Images cascade one after another (on television, on the internet, in cities turned into advertising screens), but their flow is not real, as there’s nothing connecting these images to each other or to the world. In this sense, such images no longer represent anything old, just as they no longer produce anything new: they simply circulate in the empty space of hyper-reality, reproducing and accumulating themselves to infinity, following the same abstract and empty logic of Capital.

Question: what, then, is wrong with the coexistence of the fragmented and the continuous? Nothing, because neither continuity nor fragmentation exist in absolute terms (and one cannot exist without the other). And what is wrong with linearity itself? Nothing, but only if linearity is not total, that is, if it is capable of referring to something else, to another segment that, in turn, differs from the first. In the seemingly linear space of Renaissance painting, there is, in a set of magnificent works, a depth that opens up like a wound, destabilising what we initially thought was simple and uniform. Are not the perspectival canvases of Leonardo or Perugino more immensely explosive and overflowing than television channel surfing, which only shows us, in its fragmented and accelerated form, mindless repetitions of the Identical? Why then this radical apology for fragmentation against linearity? Is it not the result of a certain dialectical obsession, which stems from the core of modern Western epistemology (which is, let us be honest, somewhat démodé), which insists on privileging the logic of oppositions: fragmented vs. continuous, pure vs. impure, good vs. bad, from which one must choose one term over the other?

An image that hurts us, that pierces us, that makes us think is always an exorbitant image (thought arises from all kinds of relationships and intersections: linear, fragmented, continuous, mixed). And the exorbitant image opens up like a fissure (or like a wound), creating relationships between planes and questioning its own status not only as an image, but also as a sign and, therefore, as reality. An image that exceeds itself is an image that exceeds its capacity to signify, its own status as an object or image, its own elementary reduction to the number 1 (only simulacra are subsumable to unity, since they no longer have a ‘double’ or “multiple” or ‘infinite’: reality shows, pornography and live television are hyper-real images par excellence, completely purged of imagination and fiction and, for that very reason, absolutely coincidental to themselves).

In no way are the screen or the frame a cage: unless the image itself wants them to be. Classic American cinema was defined by its linearity, it’s true, but that didn’t prevent it from spawning some of the most exorbitant (and disconcerting) films in the history of cinema. Indeed, in the great masterpieces of American cinema, we find images full of exorbitance, ruptures, wounds and displacements, in a conscious game of deconstruction and confrontation with the codes and limits imposed by the unofficial hegemony of the studio system (suffice it to mention Orson Welles, Fritz Lang, Ernst Lubitsch, Josef von Sternberg, Alfred Hitchcock...).

Classic cinema proves to us that where there are limits, there is escape; where there is restraint, there is desire; and where there are rules, there is deviation.

And where there is an image, there is blindness – because the image that looks at us – and pierces us – is like a dagger pointed at our vision.

Footnotes

- ^ DELEUZE, Gilles, (1981). Francis Bacon: The Logic of Sensation. Continuum, 2003, London/New York: Continuum, 2003, pp.10-11

- ^ VERNANT, Jean-Pierre (1965), Myth and Thought among the Greeks. New York: Zone Books, 2006

- ^ PANOFSKY, Erwin (1927), Perspective as Symbolic Form. New York: Zone Books, 1991, p. 27

- ^ DESCARTES, René (1641), Meditations on First Philosophy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008, p. 57

- ^ ALBERTI, Leon Battista (1435), On Painting. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008, p. 23

- ^ KANT, Immanuel (1790), Critique of Judgement. Indianapolis/Cambridge: Hackett Publishing Company, 1987, p. 98

- ^ PANOFSKY, Erwin (1927), Perspective as Symbolic Form. New York: Zone Books, 1991

- ^ BARTHES, Roland (1980), Camera Lucida. Reflections on Photography. New York: Hill & Wang, 1981, p. 26

- ^ DIDI-HUBERMAN, Georges (2004), Images in Spite of All. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, p. 81

- ^ DELEUZE, Gilles e GUATTARI, Félix (1972), Anti-Oedipus. Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Minesota: University of Minnesota Press, 1983, p. 38

- ^ Ibid., p. 39

- ^ Ibid., p. 11