The trace as a photographic remembrance of the disaster: real estate bubble in the Spanish landscape

Susana DelgadoIntroduction

The real estate crisis of the 2000s and the consequences that it did cause on the population in terms of employment, evictions, politics, etc., are one of the problems that has caused more concern to the Spanish society since democracy was established in late 70's. While part of the population lost its job, saw how their debts were increasing, how the landscape was flooded with empty houses that belonged to the banks and promoters or even unfinished houses and infrastructures that were erected as «monuments» to a wasteful time; the government began to rescue banks, savings banks and real estate developers[1]. This disenchanted population, due to the fact of seeing that they had been pushed into consumption and now they were left out of the rescue, begins to be critical with the situation and the consequences that it has brought, manifesting themselves in different spheres of the society as social movements, as well as cultural and artistic expressions. The real estate crisis has occupied the plot of Spanish films[2] or even song lyrics[3], but being the artistic and photographic projects where the subject has been represented more often and it has been done from different points of view and visual strategies. This makes sense if we think that photography has been used, very frequently, in the analysis of the environment and if we face with a complex reality, it offers information, subjectively elaborated that allows us to formulate reflections on the meaning and evolution of a place[4]. This article aims to present a critical trend in Spanish landscape photography, which arises in response to this crisis and shows the consequences through the traces that have remained and have marked the territory, sometimes, in an absurd way. Through the analysis of projects by Julia Schulz-Dornburg, Simona Rota, Kathrin Golda-Pongratz and the Nación Rotonda collective, we can see how this type of photography plays with previous visual influences, standard ways of representing the landscape and architecture and the comparison of photographs to show, in a satirical way, the consequences of the excessive alteration of the landscape made by the capitalism, without really taking into account the population's necessities or the environment. First of all, to understand what traces these images contain, we must go into the characteristics that have led the Spanish economic model to this scenario.

Context of the Real State Bubble

The recent Spanish history is intimately linked to the «brick» and tourism as a hallmark. The real estate bubble that arose between 1995 and 2007 was not an isolated event caused by the global financial crisis, but the consequences of a Spanish model of economy that already in Franco's period opted for the urbanisation of the territory as the main way of economic development for the country.

After a period of economic growth between 1985 and 1991 that was characterised by the revaluation of financial and real estate assets, interrupted in 1992 with the crisis of the European Monetary System, Spain signed the Maastricht Treaty and became part of the European Union, something that forced the country to dismantle part of its industry, obsolete and uncompetitive. With the Maastricht Treaty, public spending was reduced and there was also a reduction in interest rates, factors that will fully influence the next stage of the Spanish economy. This first cycle of growth reinforced the «Spanish real estate specialization»[5], causing the Spanish economy from 1995 to 2007 to turn to housing and domestic demand as the sole impulse of growth. Thanks to the low interest rates and the overrepresentation of construction and tourism in the Spanish economy, and despite the drop in wages and the contraction of public spending as opposing elements, the family and personal indebtedness translated into «surprising» data: the credit was multiplied by 11[6], homes went from a surplus of 9,000 million in 2000 to a financing need of 23,000 million in 2007[7], the «price bubble» made the prices of the houses to increase annually by 30% from 2002 to 2008[8], and the most visual data, only in 2005 and 2006 729,000 and 863,000 houses were built respectively, numbers that exceeded those of the United Kingdom, Germany, France and Italy all together[9]. «A report of the Ministry of Housing admits that never in the history of Spain more soil was urbanized and housing built than in the decade between 1997 and 2007, subsequent to a national land reform in the late 1990s.»[10] Due to a domestic demand based economy cannot be sustainable and because of the financial crisis broke, the volume of investment could not absorb the growth of the physical stock of houses. At that time, and after the rescue of banks and real estate promoters by the government, the bubble burst and the Spanish landscape was flooded with ghostly developments in which nobody came to live, half built suburbs that were abandoned from one day to another, absurd infrastructures that did not work at all, etc. This context led to an economic and social crisis and a sense of decline that manifested itself, as we have already stated, in different artistic areas, being a recurring topic in the photography of the territory of the last decade.

Artistic Manifestation as a Remembrance of the Disaster

The large number of architectural projects and unfinished urban developments, under-utilised or empty, phantom macro-urbanisation, abandoned public buildings or half-made infrastructures that cover the national territory have been the target of several photographic projects in the last decade. As the platform Cadáveres Inmobiliarios[11] pointed out, «this half-built infrastructures now form an indelible part of a landscape shaken by an absurd institutionalised megalomania. It is a widespread phenomenon at the national level and covers both the territorial and the socio-political levels.» These half-finished constructions have been collected by photographers as if they were traces or proofs of that crisis in order to understand how it has affected the landscape, and even if they say they do not intend to make a judgment, the very fact of documenting the disaster already contains elements of criticism. As it was said in the VI International Congress of Territorial Planning (Pamplona, 2010): «photography is a powerful tool for understanding a place, due to its nature, it has the capacity to deal with aspects that are difficult to parameterise or measure. Even if the photographic narrative is a subjective process, objective elements and attributes have been registered, such as materials, textures, surfaces, etc.»[12] These photographers that have focused on the spanish territory after the crisis, not only Spaniards or settled here since Hans Haacke[13] also made his particular contribution to this photographic «trend», who has felt the need to point out the visual consequences for the viewer to draw their own consequences, present certain influences of photographers who already treated the territory in these terms. Photographers such as the New Topographics or Land Art artists such as Robert Smithson who photographed the landscape and its alteration by the human being through the construction process itself or the traces in the territory. The New Topographics pictured landscapes, which were already photographed by nineteenth-century American expeditionary photographers, representing it with earlier aesthetic formulas to which they added certain irony, through the discrepancy between style and object. Especially Robert Adams[14], who noticed the photograph of Timothy H. O’Sullivan, as he considered that his approach to the landscape was more honest than the idea of landscape photography that had been made until that moment: «I would not have photograph the West as extensively as I did had it not been for O'Sullivan. I liked him because he seemed more honest about disagreeable fact that did many nineteenth-century photographers – less selective in favor of the picturesque.»[15] As Adams points out about O’Sullivan, photographers who have approached the Spanish landscape of the last decade have also tried to make an honest and ironic portrait of the territory through the traces left on it in the form of «ruins in reverse»[16]. That idea of «ruin in reverse» can be applied to the representation of the housing construction of the Spanish landscape, through architecture equated to ruins of the present, which are witnesses to a past that did not happen and a future that does not look likely to come. They are like the opposite of the «romantic ruin», that is, the «anti-romantic ruin»[17] that does not contain the past, only a proposal for the future. The ruins of Smithson, lacking in history in which the viewer can project their nostalgia, moving between «a before» and a «soon-to-be»[18]. This photograph of territory, with aesthetics typical of the representation of the landscape and discourses closer to documentary photography, reaches to create visual archives that collect the ruins under construction of a present-past, as a witness of what happened.

One of the photographic projects that makes a more explicit simile to the Spanish landscape as a territory full of «ruins» of the real estate crisis is Ruinas Modernas. Una topografía del lucro[19] by architect and photographer Julia Schulz-Dornburg. The art critic, Rafael Argullol, encourages US to see the book with this sarcastic and accurate introduction:

«It is difficult to choose among so many fossils of paradise. Roads that lead nowhere, beaches in the middle of the mountains, alpine ski slopes in parched steppes, tracks for invisible trains, desolate aerodromes that shelter the flight of the crows. Any of the traces is the raw material of a dream and the tomb of a nightmare. If you want to have a guide to travel to the garden of delights, I strongly recommend the book Ruinas Modernas. Una topografía del lucro. I do not think even The Imaginary Prisons of Giovanni Battista Piranesi contain so many fantasies.»[20]

Ruinas Modernas is a photographic project published as a book in 2012 by the Barcelona publishing house Àmbit. This project, conceived and carried out by Julia Schulz-Dornburg, a German architect based in Spain and author of other books such as Art and Architecture: New Affinities (Barcelona: Gustavo Gili, 2000), is one of the projects that has deepened the most in the topography of the Spanish landscape as consequence of the real estate crisis, due to the work method of the author, the investigation and putting into context after the photographic field work. The analytical and systematic tone in which she presents the photographs together with the inheriting aesthetic of the «social landscape» represented by Lewis Baltz, Robert Adams and Stephen Shore, make this book a small photographic inventory of some of the black spots of speculative construction abandoned in the Spanish geography. The working method and the presentation of the data gather more elements of the classic geographical explorations than of the current artistic photographic projects. It puts names and coordinates into the aesthetics of «no place» that these images possess. Ruinas Modernas is divided into four chapters called expansion, occupation, constitution and fiction, and includes 25 case studies scattered throughout the country. Each of these chapters begins with a brief text that helps to contextualise the type of construction that took place and the reasons for its abandonment, providing the elements to look and understand the «landscape as a cultural fact».[21]

The chapters are divided into sections referring to each geographical point and all these sections have the same fixed structure that defines each place. On the first page of each case study, the following elements are presented: name of the place, a subtitle with a certain sarcastic tone, date of construction and date of abandonment, name of the municipality and number of inhabitants, number of inhabitants expected after construction, municipality and province and finally, a plan of the municipality and of the urbanisation or residential. On the next page there is a colour aerial photograph of the area that occupies the case study, either an urbanisation on the outskirts of the city or a residential area in the middle of nowhere. In this photograph, the perimeter of the area is marked, as well as a series of red dots showing the photographed sites and a legend that provides information about the scale of the image. Right after some full-page photographs picture the landscape. On the last page there is a timeline where the time of each process is marked: processing, planning, construction and abandonment, as well as a small explanatory text of the place and a series of information such as purpose, description of the place's promotion, name, location, typology, surfaces, number of homes, name of the owner, builder, current status, date of photographic report and track or trail.

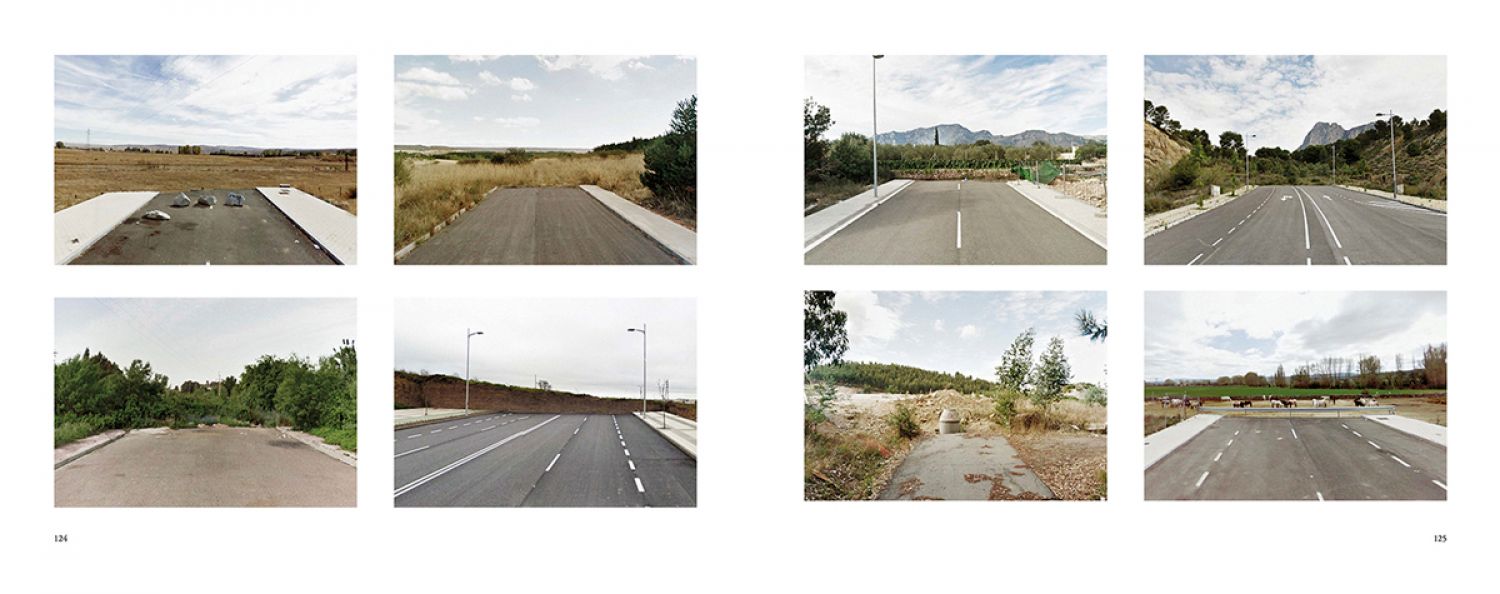

Photographs by Julia Schulz-Dornburg show a new type of landscape half built, like a frozen moment inside the construction process of a house, as in A tour of the monuments of Passaic, houses that were never finished and therefore, they never fulfilled their function of sheltering anyone. Its incomplete state is highly suggestive, its formal aesthetic of great instantaneous landscape, with high lines of horizons and diagonal vanishing points aesthetically elevate the absurd content that presents: asphalted streets that end suddenly without reaching any point, large cemented surfaces, roundabouts that only connect with other roundabouts, lampposts and electrical preparation in the middle of the field, rows of houses that have only their naked structures, streets that end in a river, network of paved and solar streets without a single built house... The disturbing beauty of these images that show the lasting physical sequelae (the footprints) that have remained in the landscape, is achieved through a «tripod» photograph, with a point of view at eye level, in very open frames and positioning the horizon in the first third of the image. In the prologue of Ruinas Modernas, Francesc Muñoz compares the images of this project with Ballardians postcards[22], dystopian visions of abandoned cities as a metaphor for the decadence of modernity, described by the writer in Low-Flying Aircraft and Other Stories[23]. These desolate scenes, without inhabitants and plagued by abandoned elements resemble the coasts of the Mediterranean and peri-urban areas, full of houses, apartments and tourist hotels that have been abandoned in the middle of the building process. This project elaborates a compilation of the «waste landscapes»[24] of the abrupt end of the real estate bubble, explicit images that seek to show the consequences of the process of indiscriminate construction of the territory. The visual information of the photograph is normally concentrated in two lower thirds of the image, leaving the upper part lighter.

According to its author, the goal of Ruinas Modernas is not to denounce the architectural nonsense or to judge the economic or political strategies of the recent housing bubble. Its intention is to expose and facilitate the reader / spectator, in the most precise possible way, the characteristics of this new topography that has been distributed throughout the Spanish geography. The book works as a visual chronicle, a forensic inventory that provides evidence and data so that each person can draw their own conclusions. As with Ruinas Modernas, other projects such as Nación Rotonda also propose that their artistic intention is not to make a judgment about what happened, but «to document the transformation of Spain and leave it as a legacy so that it can be consulted in the future and remember what it was done and what happened»[25].

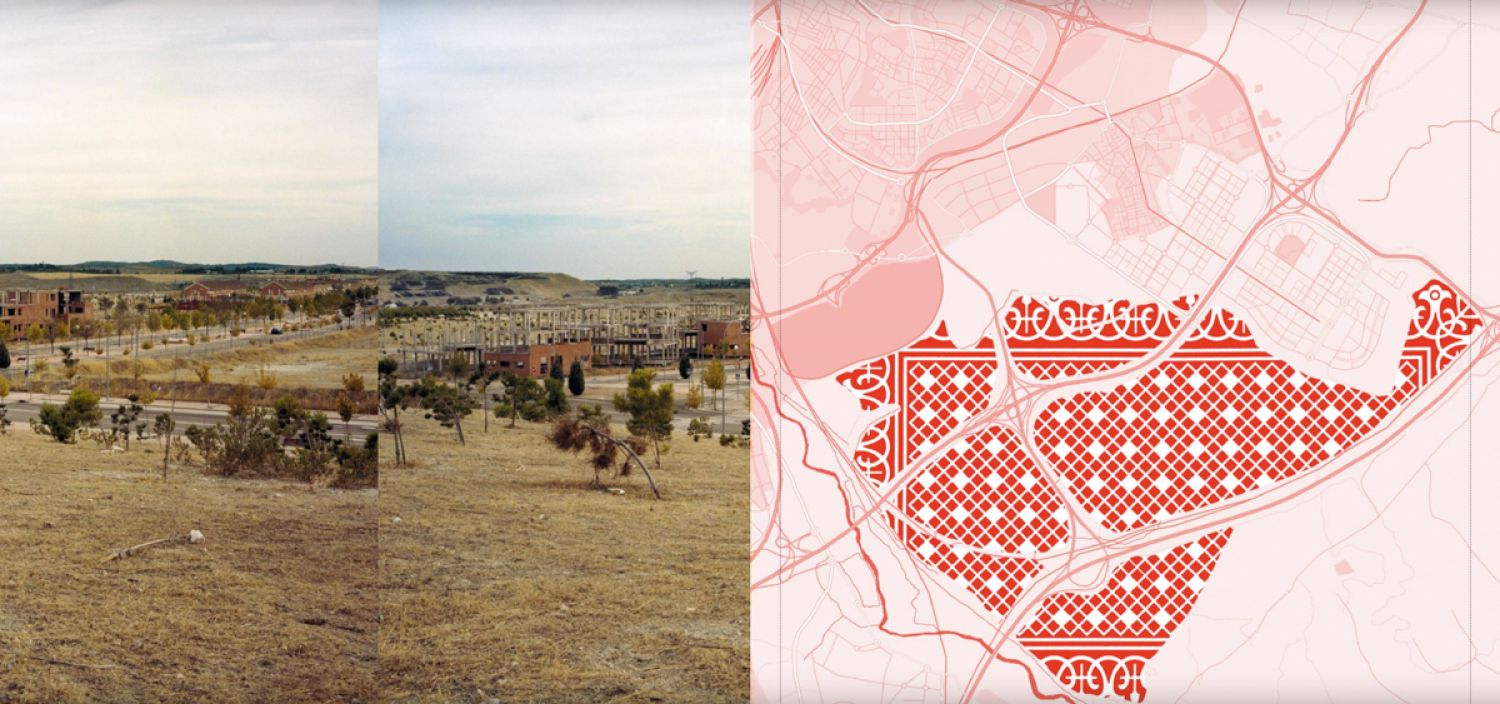

Nación Rotonda is a collective project formed by Miguel Álvarez, Esteban García, Guillermo Trapiello and Rafael Trapiello that was born in 2013 as an online platform to store a visual inventory of the Spanish urban disaster of the last 15 years, according to its own presentation. This definition constitutes one of the few texts that accompany the project, since next to the images no description appears except the date and the place. This photographic appropriation project that collects satellite images obtained through the Internet, is characterised by showing the before and after of the Spanish territory in a certain time interval to highlight the wild expansion of the «brick boom» and so absurd and paradoxical landscapes that have remained after the housing bubble in Spain. Although at the beginning it appears as a web page, later the publishing house PHREE publishes it as a book called «Libro Rotondo», a work that mixes several typologies of images in the discourse and that uses the design and the layout as a strategy to point out those excesses and such absurd traces that have remained in the landscape.

The online platform presents an interactive map where they mark with a red dot each of the places that have starred in any of the entries that the collective was periodically publishing on the web. In these entrances two superimposed images were presented, one of the before and the other of the after, that through a sliding effect, thanks to an application called jQuery, showed how the land had changed in a time interval that was normally around 10 - 15 years. For the reader's knowledge, the year's interval always appeared next to the name of the place. These images always belonged to the same typology: zenith and aerial photography that place the viewer in a distant perspective that allows them to compare and analyse the overwhelming change. Photography assumes the role of revealing the excesses and almost natural destruction that have taken place in the territory.

The book is presented as the materialisation of a visual speech of accumulation of traces: «Visual inventory of the change of use of Spanish territory in the last fifteen years, those of the real estate bubble. A critical and sarcastic tour of the urban developments of Spain»[26]. This format selects some of those aerial photos and adds images at ground level and graphic resources that help to emphasise the idea of excess and to satirise with it. These photographs include series of roundabouts decorated with an airplane or sculpture, streets that end abruptly without reaching any destination, abandoned foundations, isolated houses and lost in the middle of a network of paved streets, etc. Panoramic photographs also appear next to their respective aerial shot. As for the graphic resources, they show an aerial photograph and next to it they present the same photograph but they eliminate the landscape and leave only certain elements such as swimming pools or houses, emphasising the idea of excess and absurdity.

It is also remarkable the project Instant Village, a photographic project started in 2010 by Simona Rota, designed in three phases that concluded in 2016, this tour around the different uses that have been made of the territory in the Canary Islands. The text that accompanies the project explains that the choice of this territory as the protagonist of the set of images is based on the economic and geographical characteristics that have defined this place. The Canary Islands are a territory that depends more on tourism as an economic activity and that has led to increased pressure and territorial speculation in its development since the 1960s until the recent housing bubble of the last two decades. Being islands, the most precious natural resource is precisely the territory (for the simple fact of being even more limited than in the peninsula) thus, the seriousness of the photographic evidence of these urban practices, whose only purpose seems to be the benefit. Immediately, they have created a topography of «corrosive banality»[27], as defined by Rota. These photographs, again behave as evidence of the misuse of Spanish territory in recent years.

The represented architecture reflects the use of the territory by its authors and the power exercised by them through these constructions that have been scattered throughout the landscape. According to Simona Rota, the project is born from her personal concerns to achieve the general interest, to materialise it in images, for it, Simona seeks that the photographs have some visual appeal, through tones, framing and perspective, trying to attract the spectator towards the discourse, despite the ugliness of the architecture that they show and that they indirectly and repeatedly denounce. Instant Village seeks to reaffirm the author's vision in possible interpretations through series with a large number of images, so that the repetition makes the idea behind the project more clear and patent.

The images present an absolute absence of human figures (common to the rest of photography projects in the territory), however the presence of human beings is again represented in the traces that are materialised in abandoned constructions, large agglomerations in impossible terrains, skeletons of abandoned buildings, etc. These elements make Rota's images a powerful declaration of intentions about the human being's ability to create, transform and alter the landscape that surrounds them.

Instant Village, like many of the holiday resorts it describes, is conceptually and materially shaped in stages (an element that also appears in Ruinas Modernas). First, Instant Village I was developed in Tenerife in 2010, 2011 and 2016; Instant Village II documented the island of Fuerteventura in 2013 and Instant Village III was developed in Gran Canaria, completing the trilogy of islands most affected by urban development. This project, unlike others such as Ruinas Modernas or Nación Rotonda, focuses its study on a single territory, making it an inventory of disasters carried out in the Canary Islands. This choice is due to the personal closeness of the author to the area, where she has lived, and thus elaborates a photographic project of a concern and personal conflict. The photographs have been presented in an exhibition in PhotoEspaña 14, EME3, ALART'13 Mallorca, the collective exhibition «L» in the Kursala, etc. Currently there is a photographic selection on her personal website[28], but the goal is to publish the project in book format.

Another book that has focused on this topic is Landscapes of Pressure by Kathrin Golda-Pongratz which was originated as an exhibition that took place at the Miró Foundation (Barcelona) in 2014. The exhibition become a theoretical and critical book, which reflects on territorial policies, urban development processes and the multiple facets of productivity of a territory. It does not exclusively present photography, so it is not a photography book but it includes full-page images as the protagonist element that works as proofs of that pressure that the text explains. In Golda-Pongratz's words:

«The expansionist urban policies and planning practices of the last two decades, the creation of a real-estate bubble and its final bursting with the advent of the financial crisis have engendered a dramatic change in Spain’s landscapes. Territories where flows of global money enhanced local urban development as well as real-estate speculation are facing a sudden standstill as one of the consequences of the global financial crisis. Its impact suddenly created ephemeral architectures in a very paradoxical sense: vast planned city layouts and housing structures that have not even been inhabited a single day.»[29]

In this case, the book presents much of the analysis of the problem through the word, these texts are written (both in Spanish and English) by the author herself Kathrin Golda-Pongratz and Carles Guerra. Landscapes of pressure focuses on the territory under pressure from the Eurovegas project in Spain, highlighting the suppressed landscapes to economic and speculative pressure. The project defends that the policies that control the organisation and structuring of the territory are usually governed by the logic of the global economy, thus converting any metropolitan territory into a possible object of speculation.

The book, which can be read online[30], was a finalist of the FAD Awards Barcelona 2015 (Theory & Criticism), a deserved position since the discourse is not only present in the text and the photographs, but in the design of the box and the book itself. The book is conceived as an object that speaks of the speculation of the territory turning it into a giant casino through all its elements. The box that keeps the book emulates that of a large deck of cards, referring to the game (Eurovegas) from the envelope. Inside there are graphic motifs that allude to the backs of the cards and that fill the territory in question with maps traced in red (colour that become the driving element throughout the book as it appears the box, the back of the cards and extracts of the texts as a headline) (fig.6). Despite being a book that deals with and represents the landscape through photography, it breaks with the hegemony of horizontal format of landscape photography, playing with a vertical format with the proportions of the deck of cards, being another link to the issue it talks about.

Each of the texts that is included in the book is accompanied by different types of images within the project: on the one hand, «cemeteries» of skeletons of abandoned buildings before finishing their construction, unfinished streets that lead nowhere and even cut by mountains of earth, remains of stacked building materials, etc. These photographs show that:

«The encounters of the urban and the rural are harsh and abrupt: the liminal zones of the metropolitan area are maybe the most radical indicator for the expansionist urban policies and rampant planning practices of the last decade. These urban edges dramatically visualize the impacts of the real estate bubble itself and its final burst with the outbreak of the financial crisis and the consequent complete decadence of the recent massive housing projects over the last quinquennium.»[31]

In addition, (in this book) the design plays such an important role in closing the discourse in this book, visual games are recreated between the images of contiguous pages, establishing continuity of lines and diagonals so that two photographs can be seen as a single visual unit.

Conclusion

This trend in landscape photography towards collecting the traces of capitalism, human displacements and migrations or the violence exerted on the landscape that took place in the last decade in Spain is not exclusive to these four projects. The proliferation of exhibitions[32] that approach the landscape and its different dimensions have usually included some project that represented the consequences of the real estate bubble in the Spanish landscape. In addition, this type of discourse, in addition to exhibitions, have found in the photography book the perfect medium for the dissemination and remembrance of the disaster. From now on, it depends on society and government, to use all those lifeless structures that flood our landscape, but until that moment comes these projects will be there to point out and remember that there was a time when «migrational pressure and a growing real estate speculation of local and international investors, builders and banks and the related corruption in city councils have converted the country into a sprawled and suburbanized territory.»[33]

Bibliography

ÁLVAREZ, Miguel; GARCÍA, Esteban; TRAPIELLO, Guillermo & TRAPIELLO, Rafael (2015). Nación Rotonda. Madrid: Phree.

ARGULLOL, Rafael. (15 July 2012). El jardín de las delicias El País digital. Available: https://elpais.com/elpais/2012/07/10/opinion/1341938258_244779.html

FOLDE, Marja Skotheim, CABRERA MANZANO, David, MARTÍNEZ HIDALGO, Celia, RODRÍGUEZ ROJAS, Mª Isabel & CORDERO CARRIÓN, Lucas. (2010). «Paisaje y patrimonio territorial. Valores a desarrollar y conservar Ciudades y cambio global; hacia un nuevo paradigma territorial. La Vega De Granada. De la Imagen al Territorio». VI Congreso Internacional de Ordenación del Territorio, Pamplona, 2010.

GRAZIANI, Ron. (1994). «Robert Smithsons Picturable Situation: Blasted Landscapes from the 1960s» in Critical Inquiry, Vol. 20, n.º 3 (Spring, 1994), p. 431.

GOLDA-PONGRATZ, Kathrin. (2016). «CONTESTED_CITIES to Global Urban Justice.» Stream 2 Article n.º 2-003. Congreso Internacional Madrid, 2016.

GOLDA-PONGRATZ, Kathrin. (2014). Landscapes of Pressure. Barcelona: Le Books, Bside Books.

GOLDA-PONGRATZ, Kathrin. (2013). Landscapes of pressure, landscapes of standstill. The (sub)urban edges of Spain's metropolises after the boom del ladrillo. RC21 Conference 2013, Humboldt University Berlin.

JUROVICS, Toby. (2010). «Framing The West. The survey photographs of Timothy H. O'Sullivan» in Framing The West. The survey photographs of Timothy H. O'Sullivan. Library of Congress, Smithsonian American Art Museum. Yale University.

MINISTERIO DE VIVIENDA (ed.): Informe sobre la situación del sector de la vivienda en España. Madrid 2010, p. 8.

MUÑOZ, Francesc. (2012). «Topografías del lucro, postales Ballardianas» Ruinas Modernas. Una topografía de lucro. Barcelona: Àmbit.

ORTEGA, Patricia. (2012). «El ensanche del fin del mundo», El País. (17 February). Available: http://ccaa.elpais.com/ccaa/2012/02/17/madrid/1329504564_233277.html

PRIETO, Gonzalo. (2013). Interview to Nación Rotonda: «los casos que presentamos son tumores, todos ma-lignos». Available: https://www.geografiainfinita.com/2013/12/entrevista-a-nacion-rotonda-los-casos-que-presentamos-son-tumores-todos-son-malignos/

RODRÍGUEZ LÓPEZ, Emmanuel & LÓPEZ HERNÁNDEZ, Isidro. (2011). «Del auge al colapso. El modelo financiero-inmobiliario de la economía española (1995-2010)». Revista de Economía Crítica, n.º 12, (Second semester 2011), ISNN 2013-5254.

ROTA, Simona. (2013). «Instant Village» in Catálogo eme3_2013. p. 56.

SCHULZ-DORNBURG, Julia. (2012). Ruinas modernas. Una topografía de lucro. Barcelona: Àmbit.

SMITHSON, Robert «A tour of the monuments of Passaic, New Jersey (1967)», in Smithson, Robert, The Collected Writings. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London, California University Press, 1996.

Footnotes

- ^ In 2009 Spain was already the country of the OECD that more public money had destined to save the real estate sector, being this amount the 2% of its GDP. Seen in Rodriguez López, E. y López Hernández, I.

- ^ Films as Cinco metros cuadrados. (2011). by Max Lemcke, Techo y comida (2015) by Juan Miguel del Castillo, Hermosa Juventud (2014) by Jaime Rosales, the tv series Crematorio (Crematorium) (2011) by Jorge Sánchez-Cabezud or the documentary La Granja del Paso (2015) by Silvia Munt.

- ^ Songs as Suelo Español (Spanish Land) (2016) – by Luis Troquel feat Soleá Morente produced by Raül Fernández «Refree» and included in Breve Historia de España. En lo que llevamos de siglo XXI.

- ^ Folde, Marja Skotheim, Cabrera Manzano, David, Martínez Hidalgo, Celia , Rodríguez Rojas, Mª Isabel & Cordero Carrión, Lucas. (2010). «Paisaje y patrimonio territorial. Valores a desarrollar y conservar Ciudades y cambio global; hacia un nuevo paradigma territorial. La Vega De Granada. De la Imagen al Territorio.»VI Congreso Internacional de Ordenación del Territorio, Pamplona 2010.

- ^ Rodriguez López, E. y López Hernández, I. (2011). «Del auge al colapso. El modelo financiero-inmobiliario de la economía española (1995-2010)». Revista de Economía Crítica, n.º 12 (Second semester 2011), ISNN 2013-5254. p. 43.

- ^ Ibid, p. 46.

- ^ Ibid, p. 46.

- ^ Ibid, p. 48.

- ^ Ibid, p. 48.

- ^ Golda-Pongratz, Kathrin. (2013). «Landscapes of pressure, landscapes of standstill. The (sub)urban edges of Spain's metropolises after the boom del ladrillo.» RC21 Conference 2013, Humboldt University Berlin.

- ^ Real Estate Corpses. It is collective project that pursues the location and documentation of all these developments that died prematurely. This initiative is of a marked interdisciplinary nature, encompassing architects, engineers, urban planners, researchers, artists or environmental activists and invites the participation of as many people as possible. http://cadaveresinmobiliarios.org/

- ^ Folde, Marja Skotheim, Cabrera Manzano, David, Martínez Hidalgo, Celia , Rodríguez Rojas, Mª Isabel & Cordero Carrión, Lucas. (2010). «Paisaje y patrimonio territorial. Valores a desarrollar y conservar Ciudades y cambio global; hacia un nuevo paradigma territorial. La Vega De Granada. De la Imagen al Territorio.». VI Congreso Internacional de Ordenación del Territorio, Pamplona, 2010.

- ^ Castillos en el aire is a project that Haacke made after coming to Spain in 2010 to visit Manuel Borja Villel, director of the Museo de Arte Reina Sofía. As he reached the center of the city in the taxi he could see, in its path, huge tracts of land, with paved streets and lampposts on either side of a completely empty space: «In the middle of nowhere» he says. «When I arrived, I asked what was it and they told me that there were many such places in the suburbs of Madrid, promised lands, where large urban plans were planned that, after the bursting of the housing bubble, had been abandoned». Seen in Ortega, Patricia. (2012). «El ensanche del fin del mundo», El País. 17 February. Available: http://ccaa.elpais.com/ccaa/2012/02/17/madrid/1329504564_233277.html

- ^ Robert Adams was one of the photographers whose work was part of the exhibition New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape that took place at the George Eastman House in New York in 1975 and that helped to have a new conception of landscape representation and documentary objectivity.

- ^ Seen in Jurovics, T. (2010). «Framing The West. The survey photographs of Timothy H. O'Sullivan» in Framing The West. The survey photographs of Timothy H. O'Sullivan. Library of Congress, Smithsonian American Art Museum. Yale University, p. 11.

- ^ In the 70s, Smithson referred to the «ruin in reverse» in his walk on the highway under construction of Passaic. Seen in Smithson, Robert «A tour of the monuments of Passaic, New Jersey (1967)» in Smithson, Robert, The Collected Writings. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: California University Press, 1996.

- ^ Smithson, Robert, «A tour of the monuments of Passaic, New Jersey (1967)» in Smithson, Robert, The Collected Writings. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: California University Press, 1996, p. 72.

- ^ Graziani, Ron. (1994). «Robert Smithson’s Picturable Situation: Blasted Landscapes from the 1960s» in Critical Inquiry, Vol. 20, n.º 3 (Spring, 1994), p. 431.

- ^ Modern Ruins. A topography of profit. Barcelona: Àmbit.

- ^ Argullol, Rafael. (15 july 2012). «El jardín de las delicias», El País digital. Available: https://elpais.com/elpais/2012/07/10/opinion/1341938258_244779.html

- ^ Schulz-Dornburg, Julia. (2012). Ruinas modernas. Una topografía de lucro. Barcelona: Àmbit. p. 19.

- ^ Muñoz, Francesc. (2012). «Topografías del lucro, postales Ballardianas» in Ruinas Modernas. Una topografía de lucro. Barcelona: Àmbit. p. 8.

- ^ Low-Flying Aircraft and Other Stories a collection of science fiction short stories by British writer J. G. Ballard published in 1976.

- ^ Term used by Francesc Muñoz in «Topografías del lucro, postales Ballardianas» in Ruinas Modernas. Una topografía de lucro. Barcelona: Àmbit. p. 8.

- ^ Prieto, Gonzalo. (2013). «Interview to Nación Rotonda: «los casos que presentamos son tumores, todos ma-lignos». [Online] Available: https://www.geografiainfinita.com/2013/12/entrevista-a-nacion-rotonda-los-casos-que-presentamos-son-tumores-todos-son-malignos/

- ^ Álvarez, Miguel; García, Esteban; Trapiello, Guillermo & Trapiello, Rafael. (2015). Nación Rotonda. Libro Rotondo. Madrid: Phree.

- ^ Rota, Simona. (2013). «Instant Village» in Catálogo eme3_2013. p. 56.

- ^ www.simonarota.es

- ^ Golda-Pongratz, Kathrin (2016) «CONTESTED_CITIES to Global Urban Justice.» Stream 2 Article n.º 2-003. Congreso Internacional Madrid, 2016, p. 8.

- ^ Available: https://issuu.com/le_books/docs/96_pages_landscape_def

- ^ Golda-Pongratz, Kathrin. (2013). «Landscapes of pressure, landscapes of standstill. The (sub)urban edges of Spain's metropolises after the boom del ladrillo» RC21 Conference 2013, Humboldt University Berlin.

- ^ Examples as Paisaje y memoria (2004), Lugares al límite. El paisaje en transición de la Vega de Granada (2013), Límites del paisaje (2015), La construcción social del paisaje (2014), El paisaje revisitado (2015), Del paisaje reciente.De la imagen al territorio. PhotoEspaña 06 (2006) and Lugares comprometidos: topografía y actualidad. PhotoEspaña 08 (2008).

- ^ Golda-Pongratz, Kathrin. (2013). «Landscapes of pressure, landscapes of standstill. The (sub)urban edges of Spain's metropolises after the boom del ladrillo.» RC21 Conference 2013, Humboldt University Berlin.