Bursting the bubble: The urgent need for strong and engaged leadership

Maria Vlachou

I first came across Elaine Heumann Gurian’s writings in 2013, 20 years after I did my Master’s course in Museum Studies. I read her book Civilizing the museum in two days and I kept thinking to myself «How can it be possible that I only found out about this woman now?».

When I started my Master’s course, all students were given a free copy of the paper Excellence and Equity; it was a must-read, it was a milestone. Elaine’s book includes an article written in 1992, entitled «The importance of ‘and’: a comment on Excellence and Equity». She writes: «This report made a concerted attempt to accept the two major ideas proposed by factions within the field – equity and excellence – as equal and without priority. (…) For the museum field to go forward, we must do more than make political peace by linking words. We must believe in what we have written, namely that complex organizations must and should espouse the coexistence of more than one primary mission.»

Towards the end of the article, she writes: «It seemed to me that the most important word in the title and perhaps the whole document was ‘and’. It has occurred to me that perhaps my whole career was metaphorically about ‘and’.» This touched me deeply. Probably, my greatest ambition is that my whole career might one day have contributed towards the ‘and’.

Elaine’s words came back to me when last November I came across an article in the Financial Times entitled «Behind the scenes at Madrid’s Prado Museum». I could have not opened it, was it not for the quote right under the title: «‘Even if we never opened, we would fulfil an important mission’, says director.» So, I opened the article and I came across a museum view we are all too used to: «The role of the museum is grounded in the memory of the nation and of civilisation. We have a great responsibility to conserve the past — the history of humanity. At the same time, a museum is a tool for educating society,» says Mr. Zugaza. Conservation, however, always comes first: «Even if we never opened the doors of the Prado we would be fulfilling an important mission — the material and intellectual conservation of our collection.»

Mr. Zugaza is not the Prado Museum director anymore. It was planned that he would be leaving in the beginning of 2017. Nevertheless, I remember a Brazilian colleague coming across the news of his leaving the museum and wondering «Was he fired because of what he said?».

We are very far from a museum director being reprimanded, much less fired, because he/she doesn’t seem to understand what a museum is. For more than a century now, and although the ICOM museum definition never placed an emphasis on one museum function rather than another, most museum professionals, including museum directors, seem to be constantly facing the dilemma «Collections or visitors? Objects or people?». But this is a false dilemma, in my opinion, one that has greatly affected the museums’ relationship with the wider society. If museums were firstly about the objects, they could be some kind of research units, but they wouldn’t be museums. And if museums were firstly about the people, they could be some kind of amusement park, but they wouldn’t be museums. It’s bringing the two together, it’s the ‘and’, that makes them museums. So, no, if the Prado never opened, it wouldn’t be fulfilling its mission.

In May 2015, it was announced that Anne Pasternak would be the new Brooklyn Museum director. She was not a museum person, but she had been for more than 20 years the artistic and executive director of Creative Time, an organisation promoting innovative, site-specific and socially engaged artistic works in the public realm. I read with great intereste her first interview for the New York Times, where, among other things, she said: «I am excited to build on that ethos of welcome». I thought to myself, «That’s it, she’s got it! She knows who this museum is». A few months later, I received a newsletter which was also shared on the museum’s Facebook page, signed by Anne Pasternak, where she shared the feedback she got after consulting the people, the museum community, regarding their expectations. Some of that feedback was:

«Many of you took this as an opportunity to share your gratitude and memories.»

«Your appreciation that our museum is accessible and welcoming was heard loud and clear.»

«You were also very vocal about your love of our ‘largely overlooked’ collections.»

«You want us to continue to offer space for the community to discuss and explore art and current issues.»

And she added in the end: «Tell me, have I missed anything?».

Anne Pasternak showed people that she was eager to get in touch, to listen, to learn and to work on something more, something larger, than simply her own agenda. I thought, «Great, let’s see how she puts all this into practice».

It didn’t take long. In October 2015, the museum came under heavy criticism for renting one of its spaces for a Real Estate Summit. People – including artists, critics and writers – were witnessing daily displacement and tenant harassments, artists were losing their studios, etc. etc. They didn’t feel that this event was compatible with the museum’s mission and they made it known. So, now what, Anne Pasternak?

A few months later I came across this article in the New York Times: «Brooklyn Museum puts artwork from its critics on display». The director had invited some of the demonstrating artists to present their work in an already planned exhibition, Agitprop!. She said: «I’m actively thinking about what might be out there to support affordable housing, live-work spaces for artists and contribute to a kind of community vibrancy. This is not normally a thing that I think most museum directors actively engage in or think about, but because of the conversations I have had with these artists, it is actively on my mind.» I would add: this is not normally a thing museum directors admit – that they don’t know everything, that they can learn about and become more sensitive towards some issues by listening to others, that they can become more aware and look for ways their museums can become part of the discussion.

Which brings us to the bubble.

Many people, inside and outside the UK, were shocked with the result of the Brexit referendum. They felt lost, they were unable to recognise what their country stood for in that result. People who voted for Brexit were considered stupid, ignorant, racist. A short time after the referendum, the National Theatre director, Rufus Norris, announced a series of commissions for new plays that would discuss Brexit. He said: «I don't believe 17.5 million people are racists or idiots. I categorically don't. I think we've got to listen. We've got to try to do what little we can to address the complete vote of no confidence in our system.»

Two months after this interview, we have the US presidential election and even more people feel utterly shocked with the result. Once again, Donald Trump supporters are seen as ignorant, racists, islamophobists, misogynists, etc. And once again, someone from the cultural field, BBC producer and filmmaker Adam Curtis, takes a different approach. In an interview entitled «Is the art world responsible for Trump» he said:

«The astonishing thing in my country after Brexit – and I think probably you’re seeing it now after the election of Trump – is that all the metropolitan hipsters looked around at each other and went, ‘Fuck, where did those people come from?’. They didn’t even know that Trump supporters and Brexit supporters existed, because they were so in their little bubble they just couldn’t see them. What then happened is that they started blaming those people, which I thought was pretty bad. You’d hear in bars, ‘God, the really stupid people are in control now’. And I just wanted to say, ‘No, hang on, you’re stupid: you lost the election.’ Instead of trying to blame people for voting, they should go out and find out what is really going on, bring it forward, and try and show why people voted like that. And to do that, you have to identify where real power is in our societies.»

Adam Curtis was addressing culture professionals. So, thinking about cultural organisations, the questions is how do we create and feed the bubble?

– By assuming the role of gatekeepers and wishing to control and condition everyone’s experience in the museum;

– By dialoguing only, or mainly, with our peers and longtime visitors and valuing their views more than anyone else’s;

– By using a technical language that most people don’t understand and putting the focus on technical subjects that don’t mean anything to the “uninitiated many”;

– By not making newcomers feel welcome and comfortable;

– By not making an effort to share our knowledge with a wider, diverse, audience;

– By not giving people the opportunity and freedom to make their own, meaningful, connections.

Our whole behavior, everything we communicate and the way we communicate it, make people perceive museums as an exclusive place for a privileged few. I wouldn’t get fooled with growing visitor numbers. Should we look at profiles, little has changed. And this comes as no surprise. What could really change if the way we do things hasn’t?

As the late John Berger put it in his book Landscapes, «Anybody who is not an expert entering the average [art] museum today is made to feel like a cultural pauper receiving charity.»

What visitors mostly get in an exhibition currently showing in Lisbon is label after label stating «Untitled». But it starts much before one enters the average art museum. From time to time, I open the city’s cultural agenda and go through the exhibitions. Rarely does a title stand out, mean something to me. And there can be a lot in a title. The title reveals an intention, the title is the first invitation. There is a huge difference, in my opinion, between the following two titles:

– Brueghel: Masterpieces of Flemish Art – a quite common title (especially the use of the word «masterpieces», which reveals so little to so many), putting the emphasis on the subject-matter, leaving us wondering what does «Flemish art» mean to most people;

– and Class Distinctions: Dutch painting in the age of Rembrandt and Vermeer, a title which clearly, to me, reveals an intention, an intention to make a connection, to bring collections «and» people together.

Communication works on different platforms, it combines different media. So, while we may see just a poster in the street and find just a title in a cultural agenda, we may also receive a newsletter or consult a website that would complement that information. More and more often, I receive newsletters whose subject and then content reveal very little to me. Although they are a means that may convey more information and try to create the first connections, they don’t go much further than reproducing a poster. Sometimes, there is an actual invitation text that should give some extra information. More often than not, it’s an indecipherable paragraph written in specialised jargon. Many times, I think to myself: «How many specialised books does a simple person have to read in order to understand what should be a simple exhibition summary?»

If one is capable of overcoming the feeling of ignorance and inadequateness this kind of communication provokes and actually enters the museum, if not confronted with «untitled»s, he/she is confronted with specialised contents (far from what could be considered «for the general public»); or with really basic, not very meaningful, facts (such as title, name of artist, date of birth, materials used, inventory number); or with no information whatsoever about the works.

A lot of discussion went on one of these days on the Museum Texts Facebook group regarding a teacher’s visit with her students to a contemporary art museum in Lisbon. Here’s the dialogue the teacher shared with the group:

Teacher: Careful! You cannot step on the metallic square.

Student: We can, we’re supposed to step on it.

Teacher: No, it’s a work of art.

Student: How do you know, it hasn’t got a black cord around it.

Teacher: There’s something written, I can’t read, the letter is too small (by this time, the guard is approaching worryingly).

Student: I´ll step on it, it’s not art.

Teacher: It’s got a label. It’s a museum object. You cannot touch it.

Student: Ah...OK... («this is not art», whispers the student)

The label of this artwork didn’t say much (name of artist; country; title of work; materials used). This is the kind of thing that makes people go away thinking «Is this art?», «Why are we supporting this?» or «My 4-year-old could have done this».

So, we keep things to ourselves and share them with some friends and peers. There’s no intention, no interest or no capacity to connect with people; with other people, different people. We just give the idea that we are an intellectual elite, feeling content in being congratulated by our peers and usual patrons, rarely considering the needs of other people who have an equal right of access, of being part, of being challenged, of learning, of thinking. But these people exist. We may prefer to ignore their existence, but they are there. And they are not necessarily ignorants, idiots, racists, fascists or simply uninterested.

Back in 1853, British naturalist Edward Forbes considered that «[Curators] may be prodigies of learning and yet unfit for their posts if they do not know anything about pedagogy, if they are not equipped to teach people who know nothing.» Adapting this into our 21st century language, we could say that curators or museum directors may be prodigies of learning, and yet unfit for their posts if they don’t have the courage and humility to do things differently; if they can’t put their wealth of knowledge into use in order to create connections; if they are not willing to learn from others and to consider other people’s concerns; if they are unable to reveal the relevance of the institutions they are heading; if they prefer to live in their comfortable, cosy bubbles. If they are not willing to share.

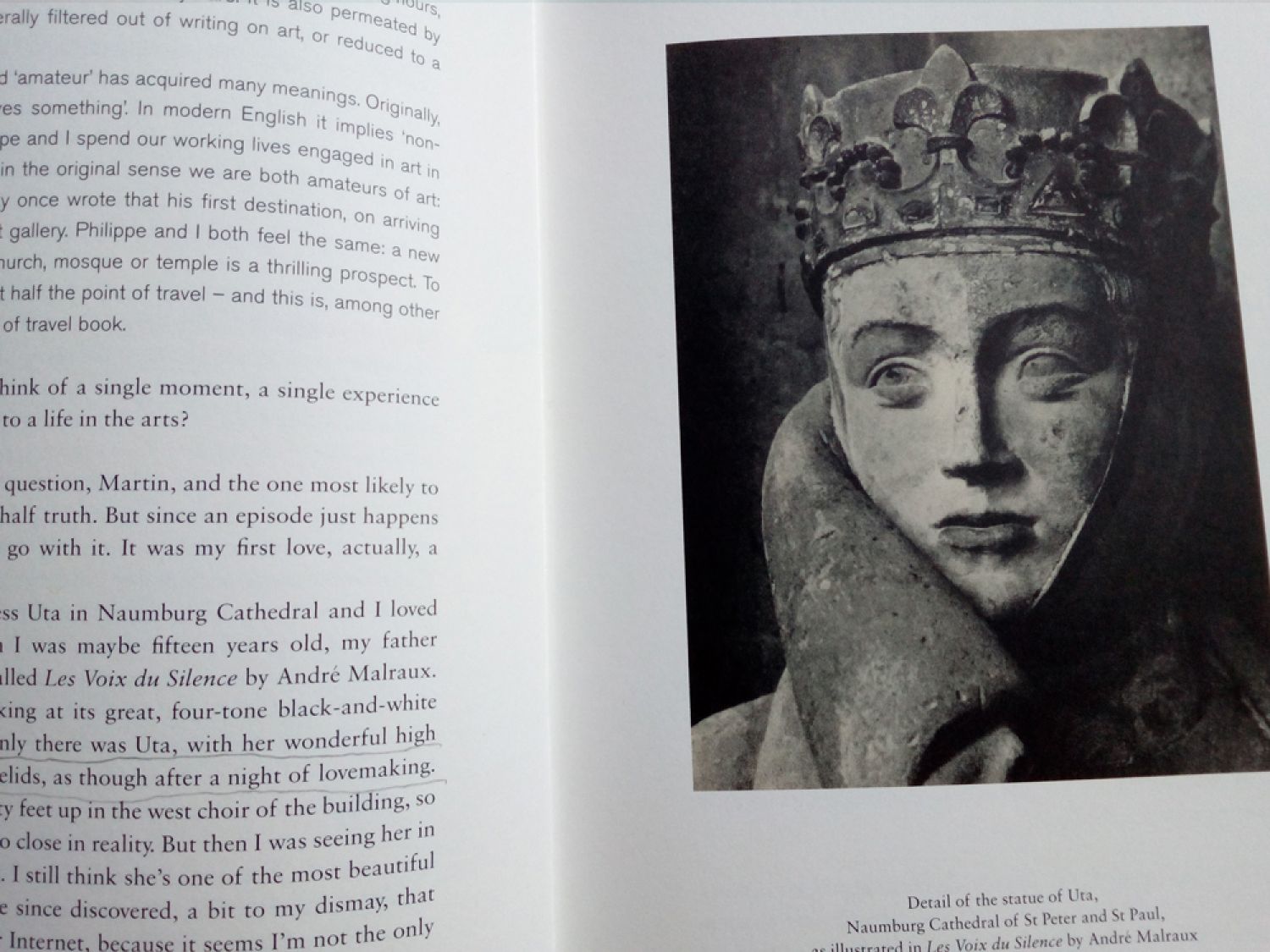

I am not someone who feels attracted to medieval sculpture. It seems that I don’t even notice it when I am next to it. A piece like the statue of Uta at Naumburg Cathedral of St. Peter and St. Paul would not make me look twice. We can imagine that the label for such an artwork could be something like this:

«Detail of the statue of Uta

Naumburg Cathedral of St. Peter and St. Paul

The sculptures were created in the middle of the 13th century out of Grilleburg Sandstone. Ten of the figures are merged with the walls, two are free-standing. They were originally painted but those remains of paint visible today date from restoration work in the 16th to 19th centuries. For early Gothic sculptures, these figures are extremely realistic and show a large amount of individual detail. The character of the sculptures and the very presence of figures of lay people in such a prominent place in the church make these unique in 13th-century European sculpture.»

But then, when art critic Martin Gayford asked Philippe de Montebello (the long-time Metropolitan Museum Director) «Philippe, can you think of a single moment, a single experience that might have led you to a life in the arts?», de Montebello answered:

«That’s the toughest question, Martin (…) It was my first love, actually, a woman in a book. She was Marchioness Uta in Naumberg Cathedral and I loved her as a woman. When I was maybe fifteen years old, my father brought home a book called La Voix du Silence by André Malraux. I leafed through it, looking at its great, four-tone black and white illustrations. And suddenly there was Uta, with her wonderful high collar and her puffed eyelids, as though after a night of lovemaking.»

At which point, I looked again, at her eyelids; de Montebello made me look again and I saw the beauty in this artwork, there was a connection. I remember thinking, «Would he ever share something like this on a museum label?»

To everything I said before – about courage and humility and connections and relevance – allow me to add one more thing: we will be unfit for our posts if we are unable to share our humanity. Because, no matter what kind of objects we are taking care of, they are firstly and most of all about human life, human stories, those of common and uncommon people. And this is what can bring us closer together. This is what can help us burst the bubble we live in and connect to the real world, the people around us. It is urgent that we do so. We need strong and socially engaged leaders in our field to help us do so.