Foma Jaremtschuk: art from beyond the edge

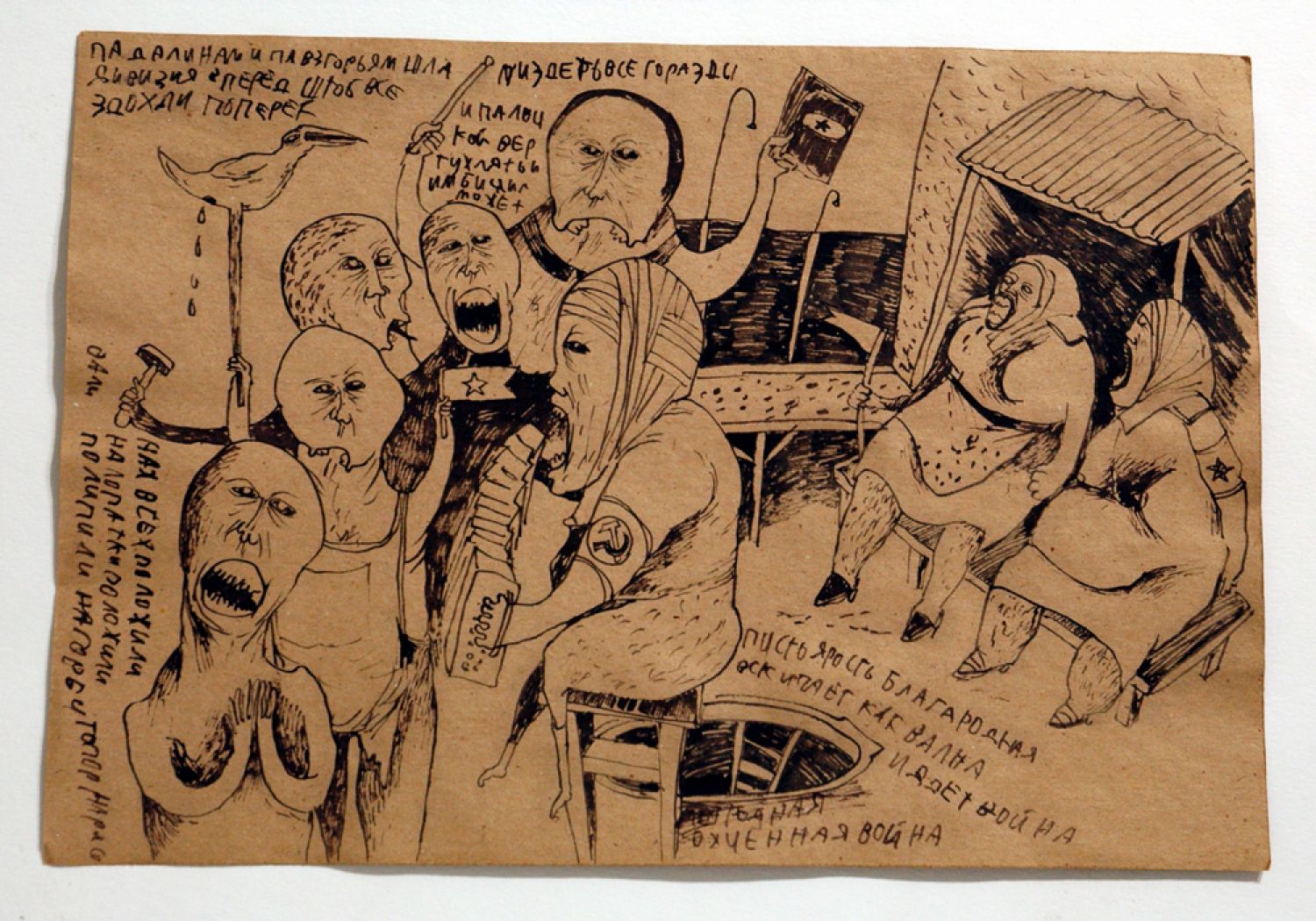

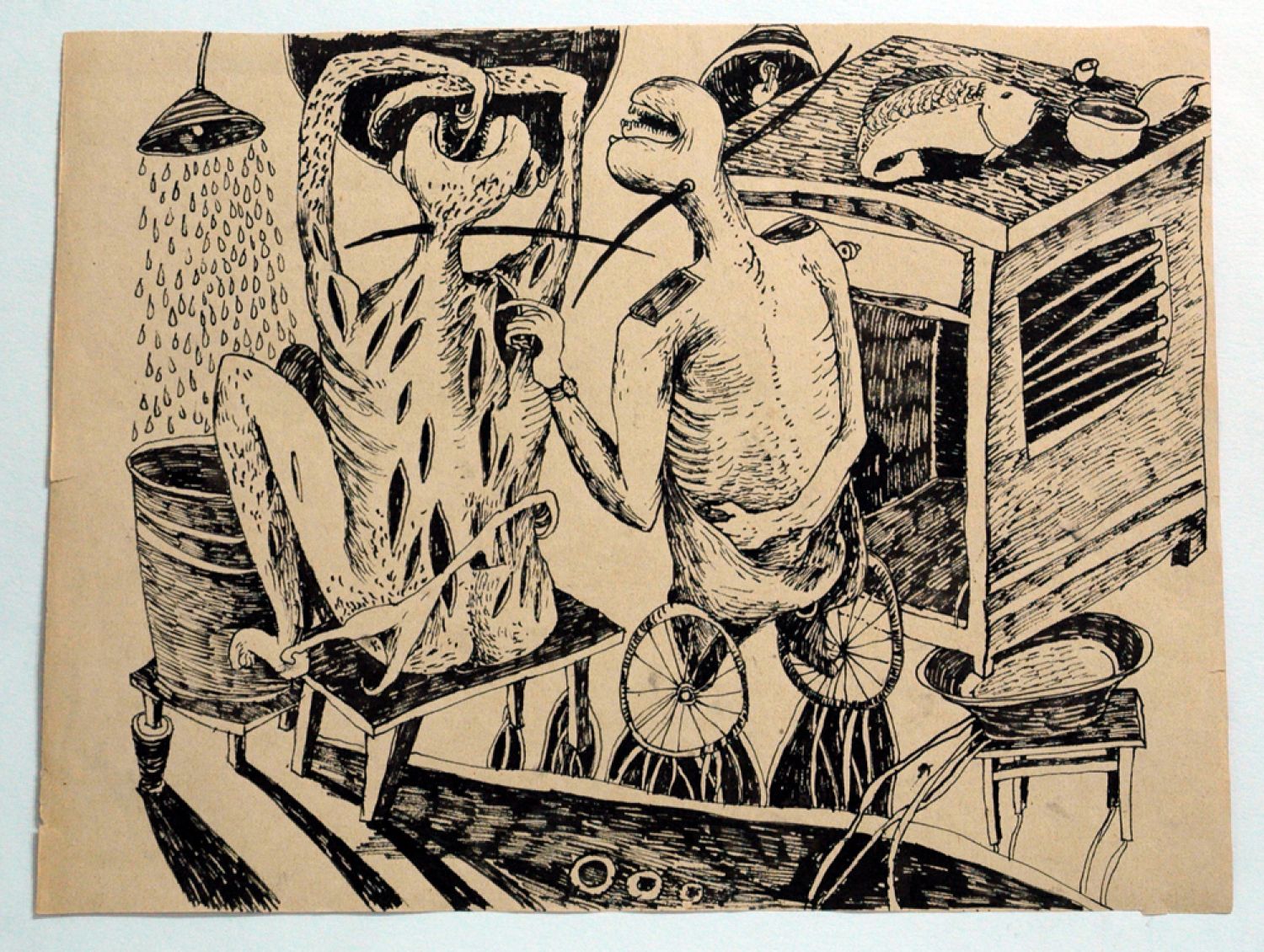

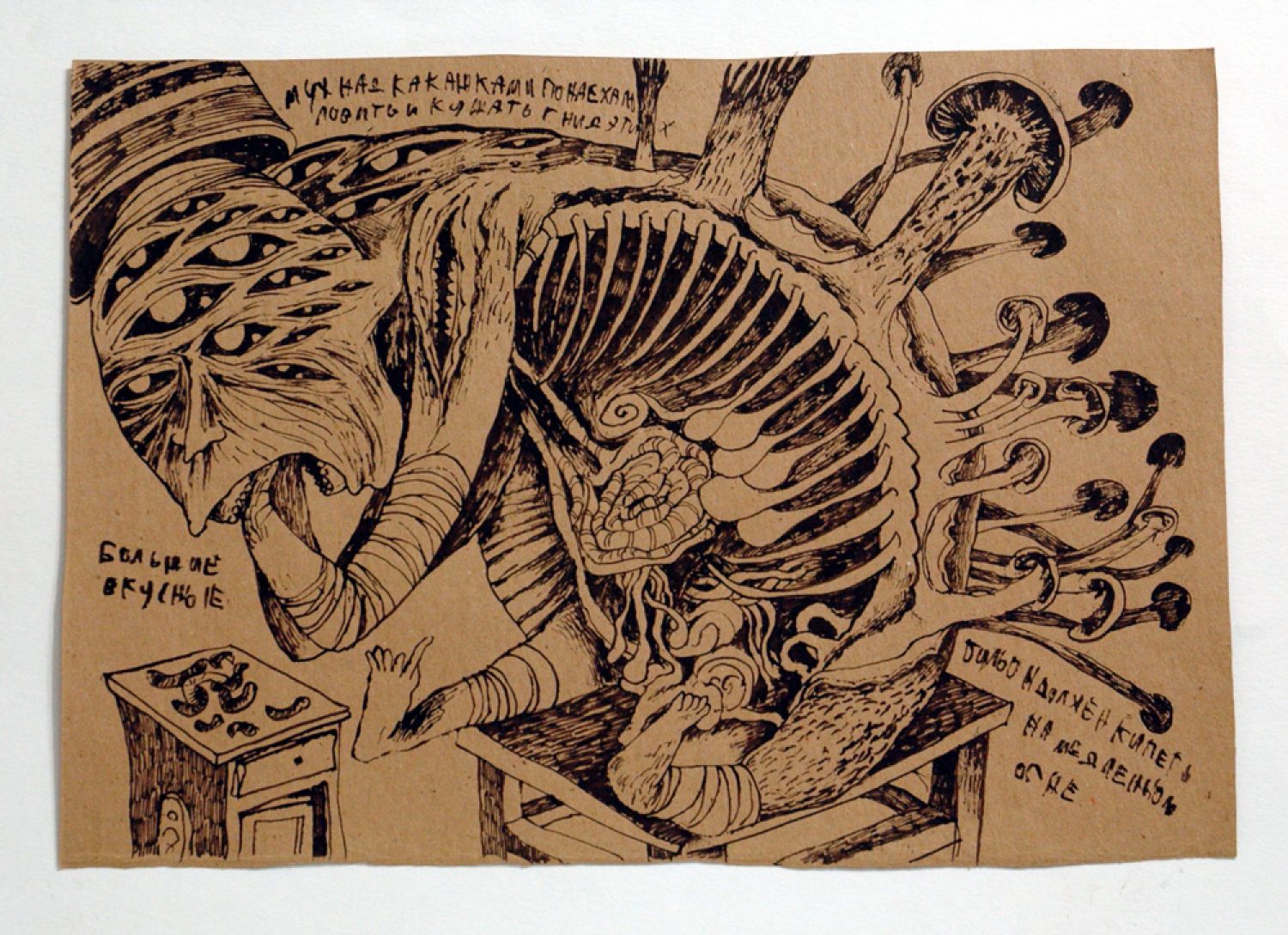

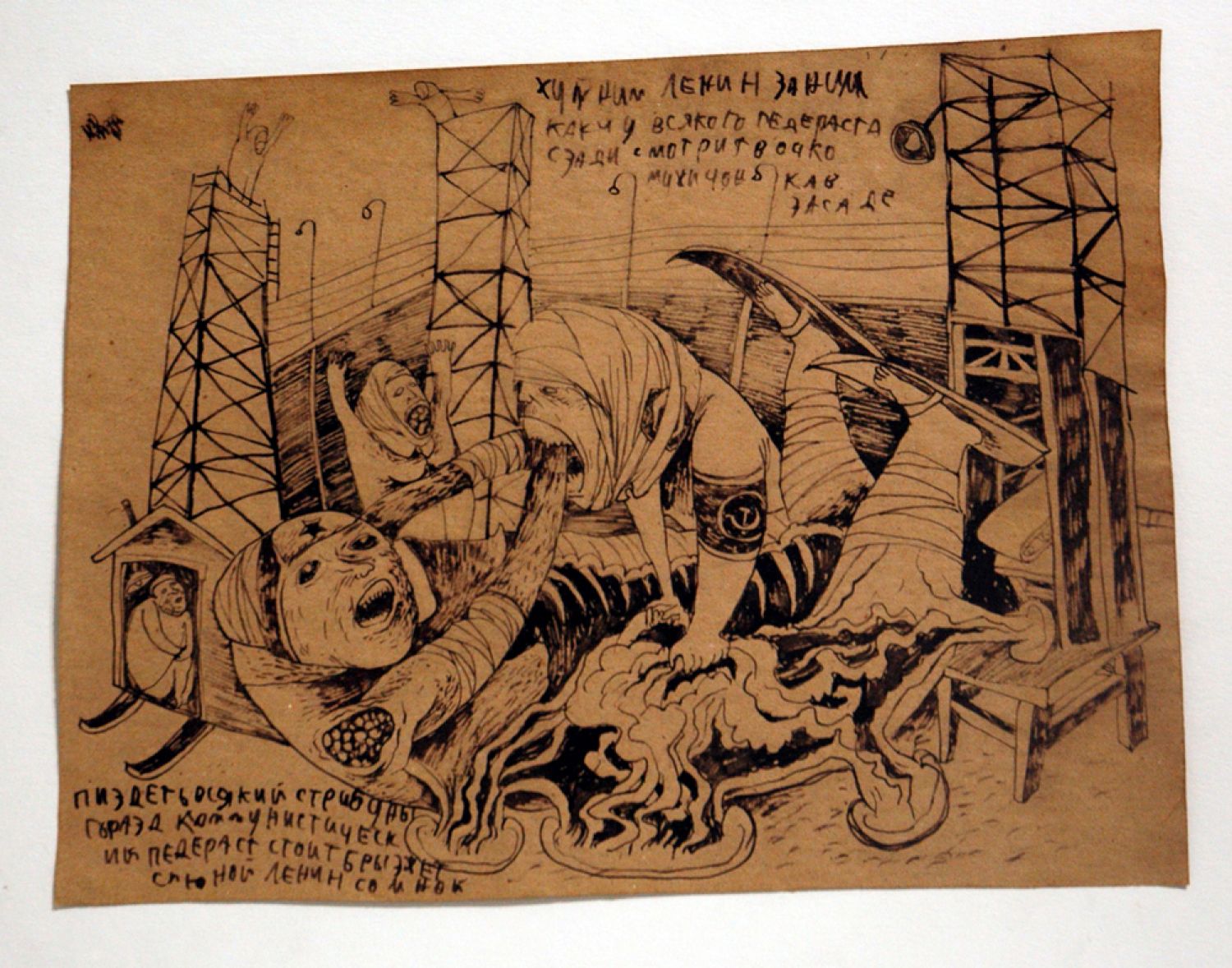

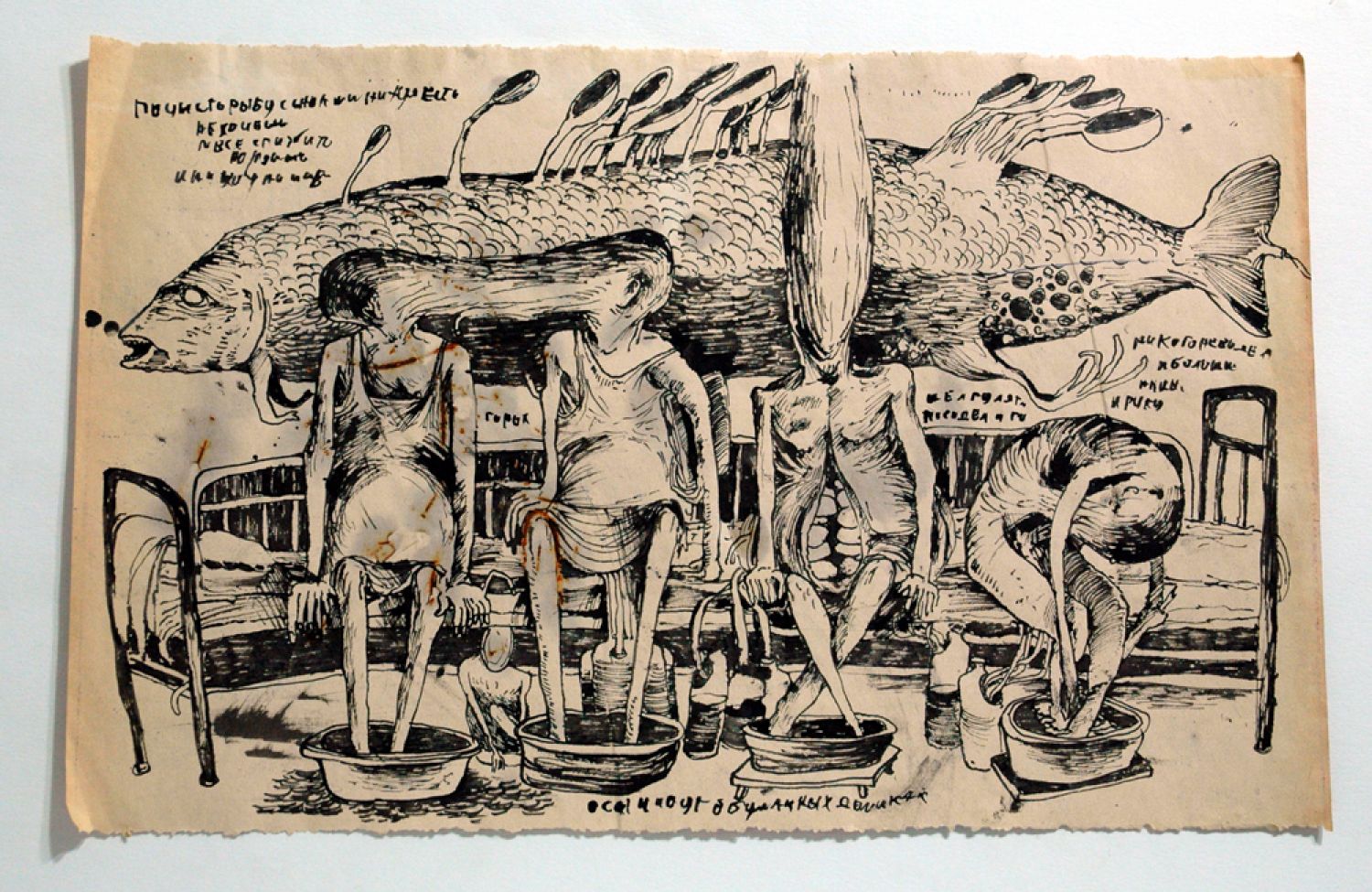

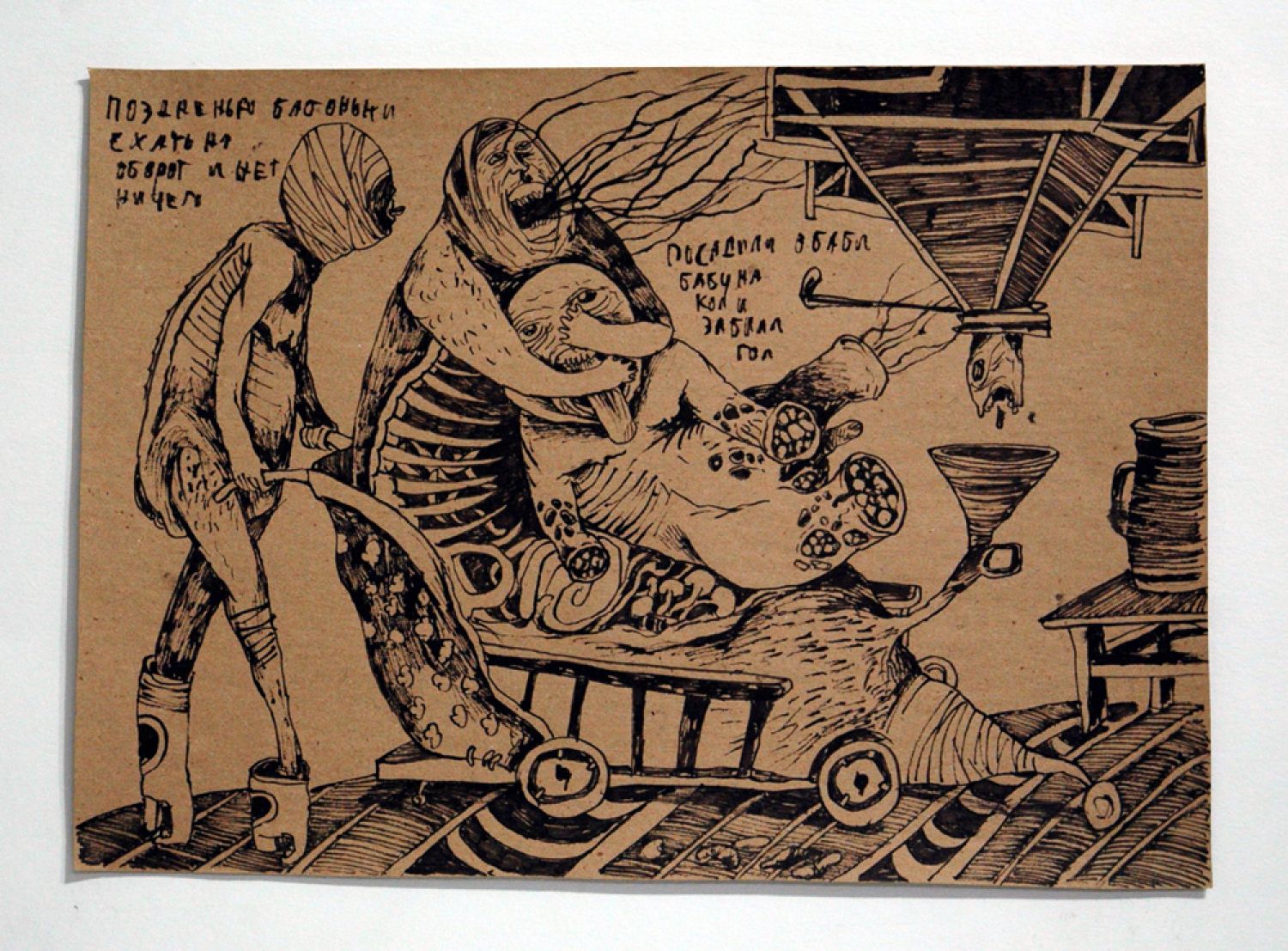

Colin RhodesFoma Jaremtschuk is an artist of immense, spontaneous power. Though completely untrained and using only the simplest of materials, he created out of appalling living conditions a pictorial universe that is utterly compelling; at once horrific and a thing of terrible beauty. His cast of characters include large female nurses and guards, deformed doctors and orderlies, and a vast array of grotesque inmates and patients, including creatures that are hybrids of human, animal and machine. They interact in a surreal world, reminiscent in feeling to Franz Kafka’s nightmare spaces. Bathtubs take on the form of living, malevolent things, cupboards and ovens always seem to contain bodies or fish. Electrical equipment functions autonomously as shape-shifting device. As often as not his images are punctuated with fragments of angry and accusatory text that characteristically reduces to a kind of indistinct textual mumble, or develops into little rhymes whose charming simplicity jars with their profane content. These drawings are a unique record of a particular time and place in the USSR, created by an individual who was supremely sensitive to their most profound reality. In many drawings he faithfully described walls, fences, lights and loudspeakers that encircled the camp and ensured that there could be no escape. And if we were in any doubt as to in whose name these penal settlements were erected, the hammer and sickle flag of the Soviet Union and Comrade Stalin appears often on camp buildings.

We know very little about Jaremtschuk from the official record. Were it not for the survival of an extraordinary body of drawings he produced he would no doubt have disappeared into that mass stream of humans that come in to the world and leave it without leaving any lasting individual mark. Yet his life spanned most of the twentieth century. We know that he was born in a remote Siberian village in 1907, a decade before the revolution that was to change the Russian Empire forever and whose new social order would shape his adult life emphatically. And his death in 1986, in a psychiatric hospital for seriously ill and untreatable people, came only five years before the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

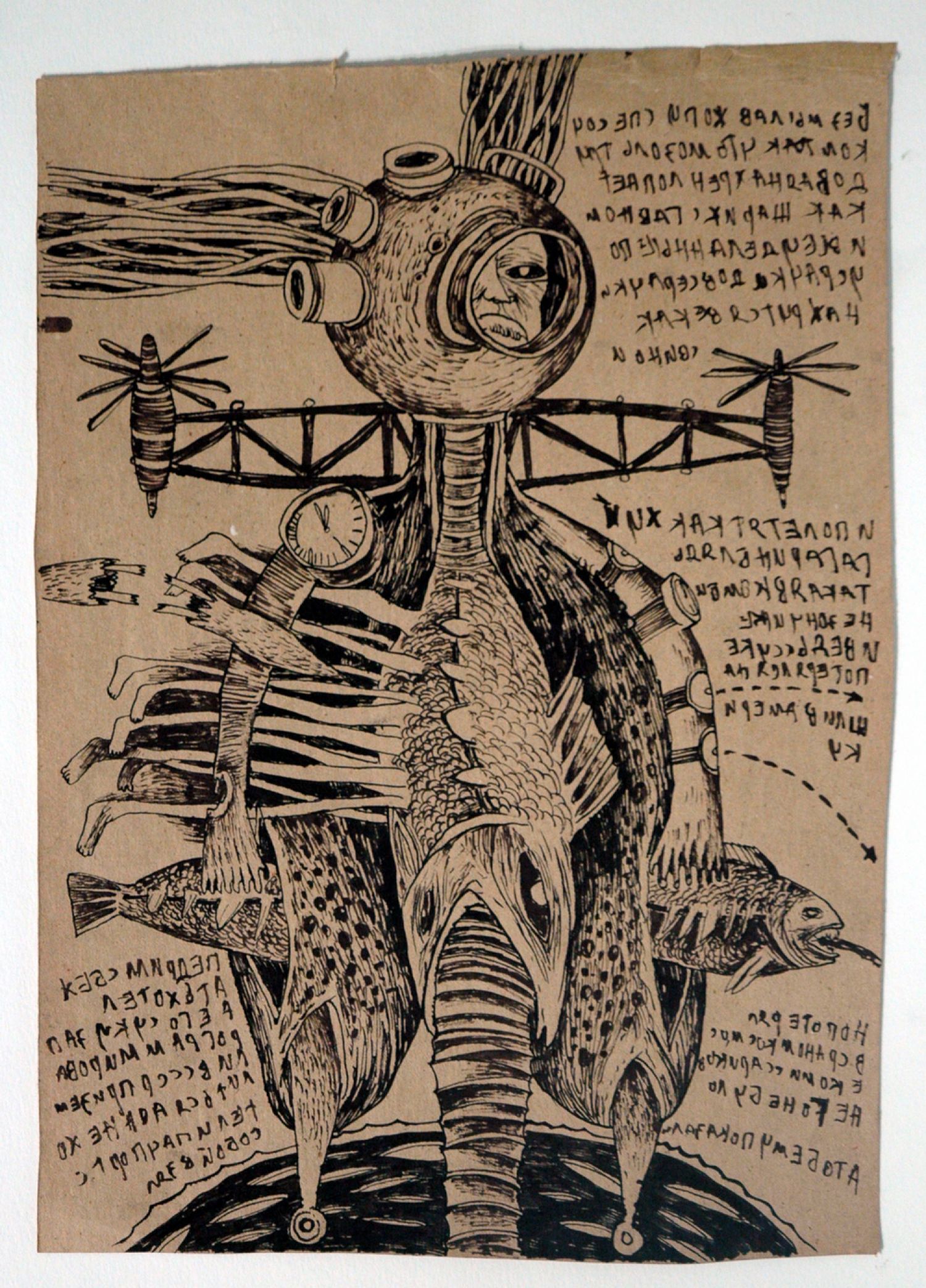

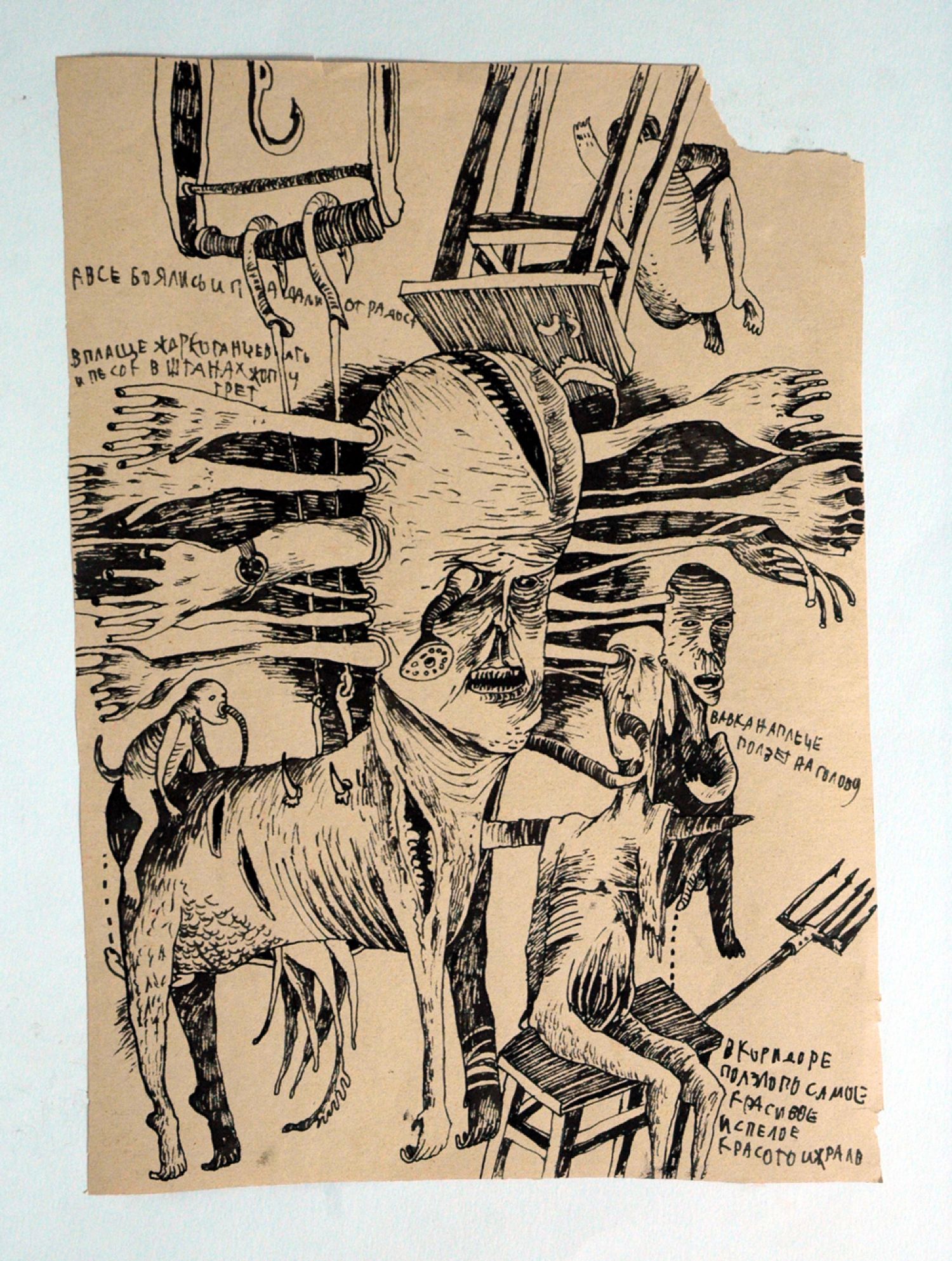

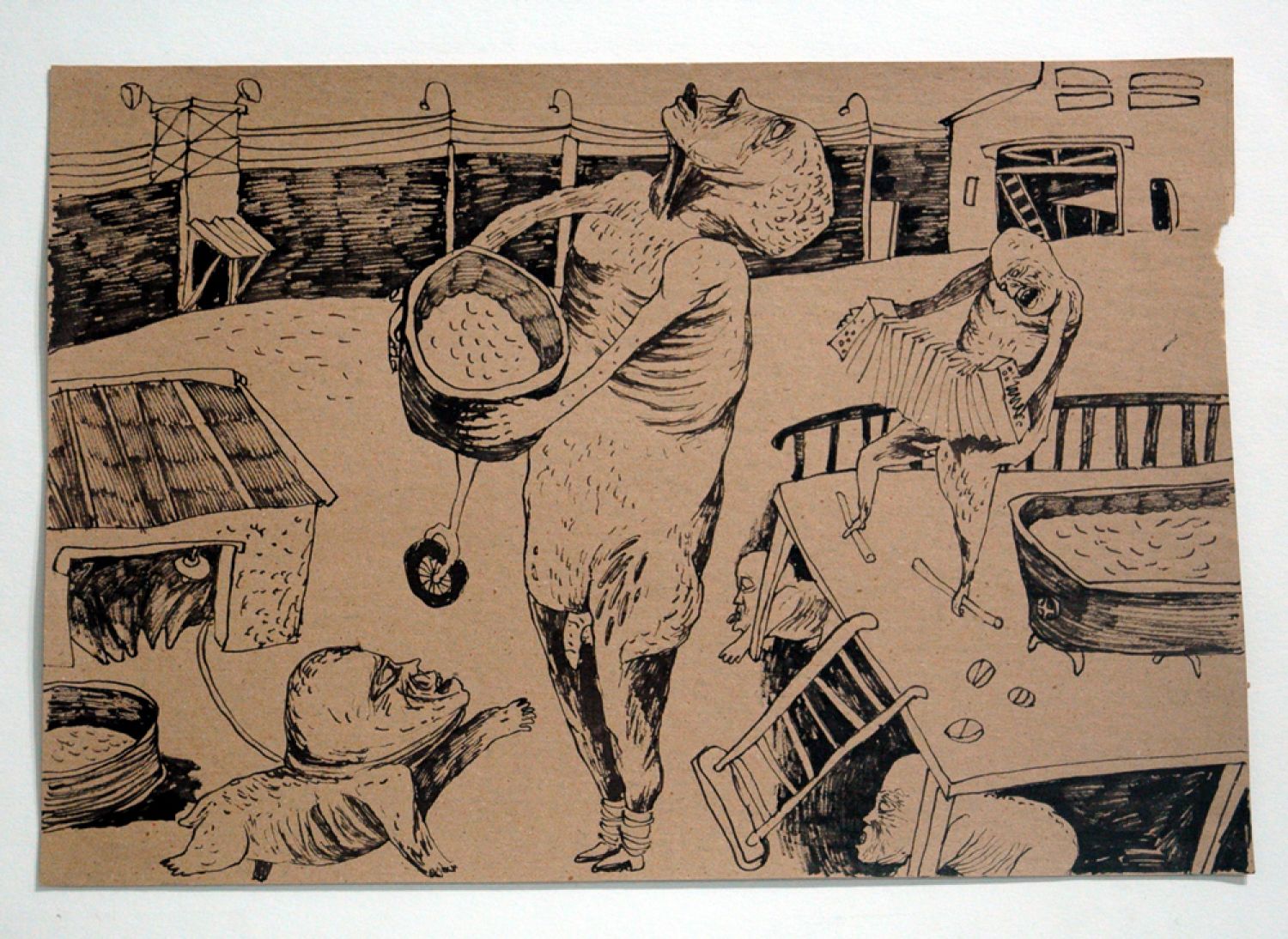

At present, other than knowing that he completed only three grades in a rural primary school, the first twenty-nine years of Jaremtschuk’s life are a blank, though the scrawled text in many of his drawings also shows that he did learn to read and write passably at some point. As far as we can tell, he never took drawing lessons. We can surmise that Jaremtschuk dissented from Stalinism, because in 1936 he was arrested and sued for slandering the USSR and like countless others he was sent to a labour camp. Or perhaps he just habitually spoke words as they came him, not thinking about any wider implications of his utterances. Either way, the result was the same. The drawings that we know often directly attack the social order, though. For example, in Organised singing (Fig.1) a group of people gather in a prison camp to sing patriotic songs. Some wear Soviet insignia. All are grotesque, rendered bestial by their circumstances and unthinking surrender to the ideology which put them there. His later reaction to Yuri Gagarin’s groundbreaking flight into outer space in 1961, and those celebrating around him, in the drawing Fly like a cock Gagarin (Fig.2) is also characteristically vehement. The cosmonaut is depicted as an amalgam of human, machine and fish. He remains secured to the tiny Earth that he rises above by a heavy column of vertebrae, and to the Soviet system by two tangles of electric wires. If there is any ambiguity in the image, the text leaves us in no doubt as to Jaremtschuk’s disdain: Gagarin is «a cock... a slut in a flying suit», and the people are «in shit to shitting themselves» and «everyone will get drunk like swine».

Jaremtschuk’s experience in the labour camp will have been appalling. Conditions were harsh, facilities were inadequate and they were usually overcrowded. Rations, clothing and medicine were poor. Writing in 1938, the procurator of the USSR, Andrei Vishinsky observed that, «Among the prisoners there are some so ragged and lice-ridden that they pose a sanitary danger to the rest. These prisoners have deteriorated to the point of losing any resemblance to human beings. Lacking food... they collect orts [refuse] and, according to some prisoners, eat rats and dogs»[1]. People like this appear time and again in Jaremtschuk's drawings. They can seem at first like deranged fantasies, but should, perhaps, be more properly understood more properly as caricatures of observed life.

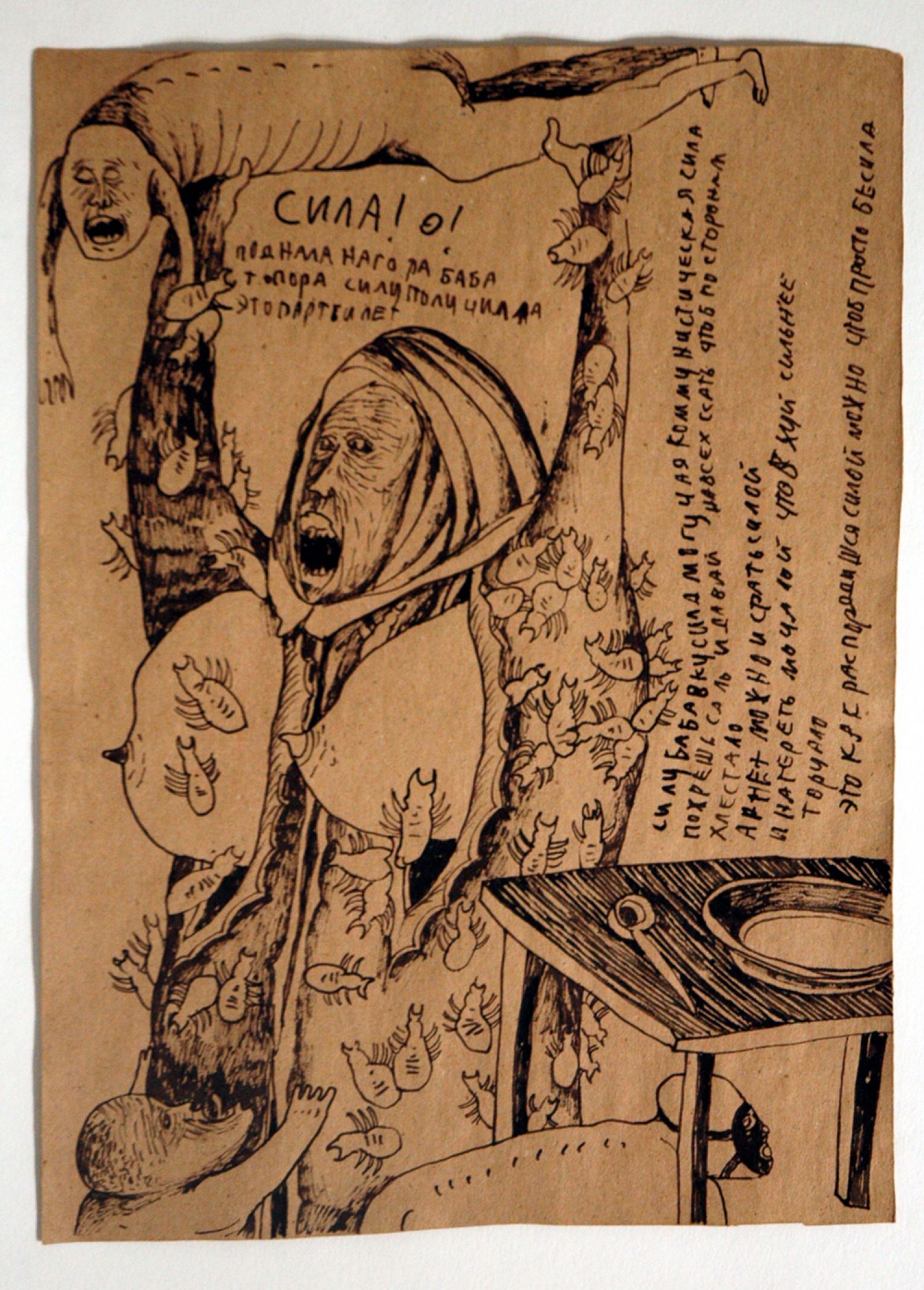

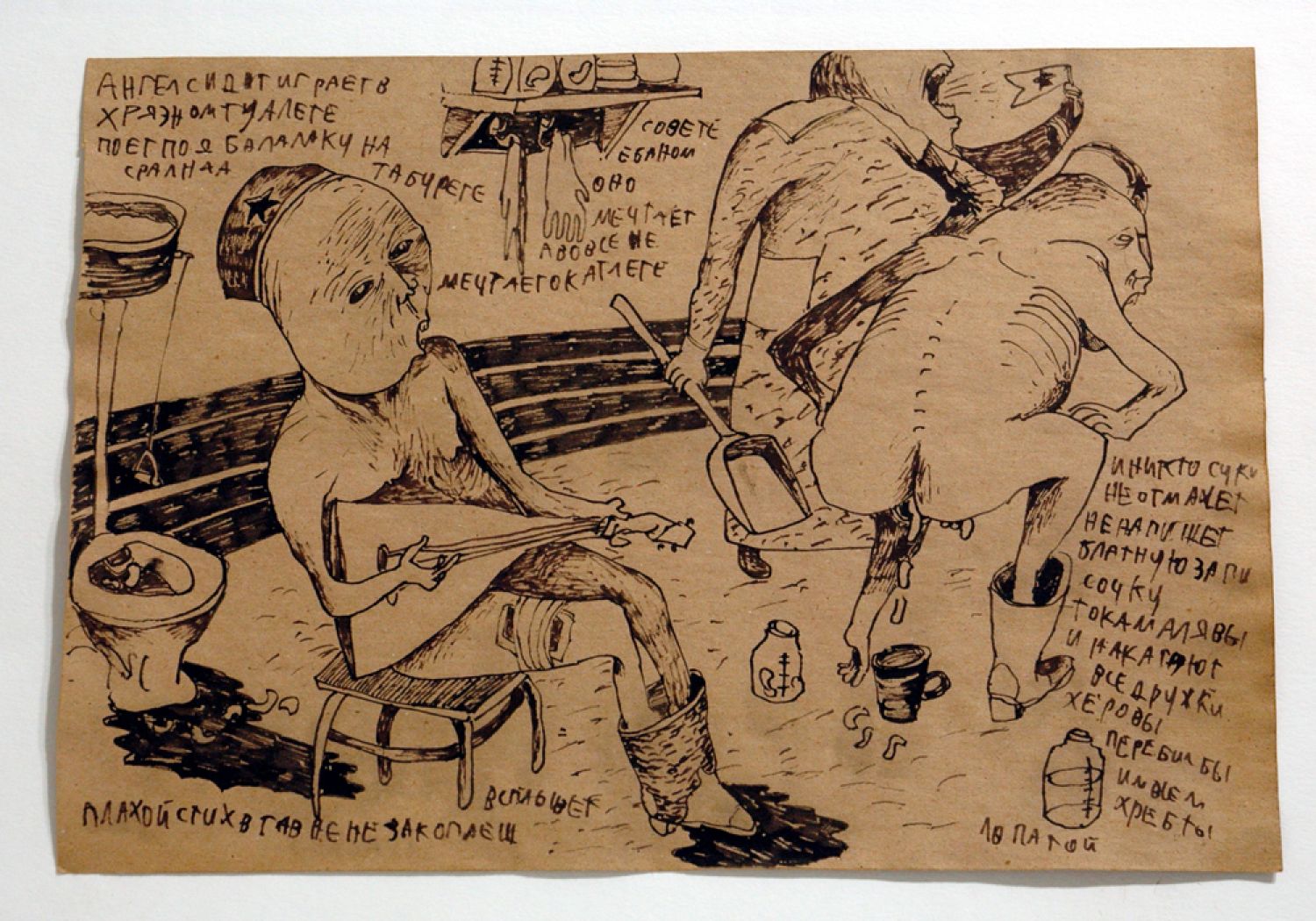

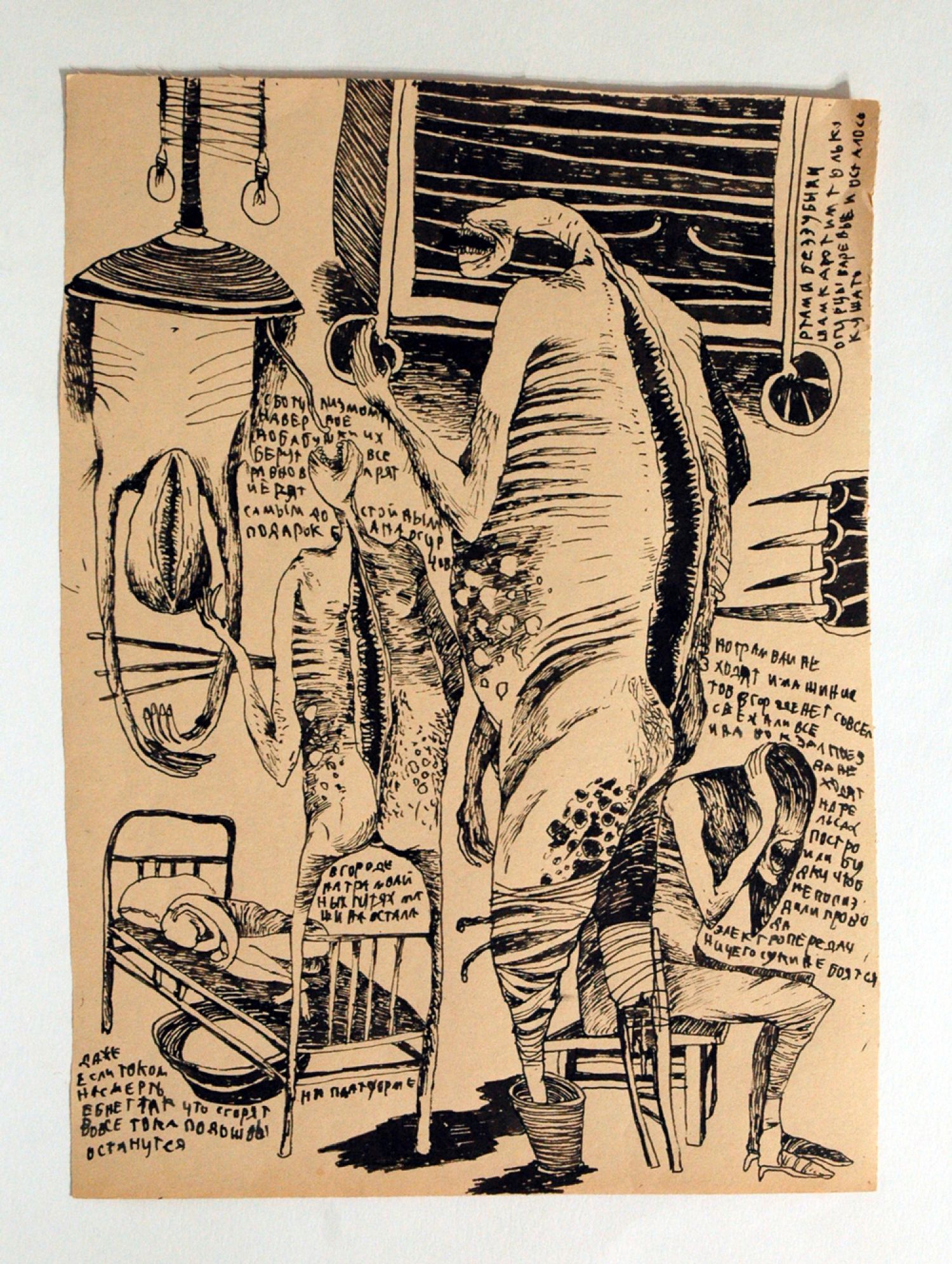

The large nurse in The woman felt the taste of force (Fig. 3) is literally covered in huge ticks that seem to feed on the awesome power she appears to have gained from Communist Party membership (the text reads in part, «the woman felt the taste of force mighty communist force you can eat lard and piss on everyone»). Similarly, there is an awful poignancy in the balalaika-playing «angel» in You can’t dig a bad rhyme in shit, it emerges (Fig. 4). The musician sits on a low stool in front of a toilet bowl, with pants around his ankles, serenading a crouching man who defecates on the floor, while a large, shovel-wielding female guard barks orders.

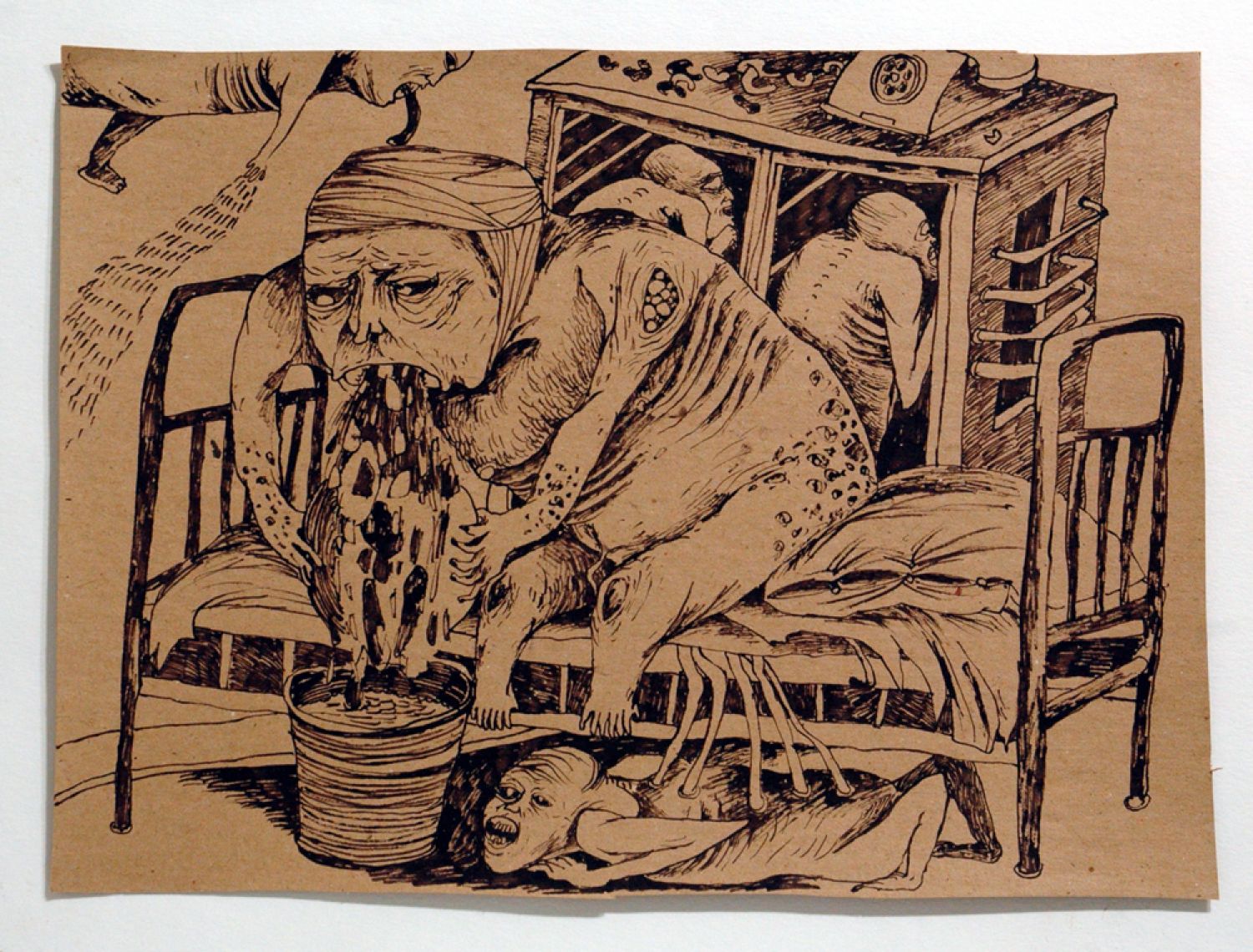

In many ways drawings like these have affinities with work by artists like George Grosz, Otto Dix and to some extent, Max Beckmann. Dix and Grosz, in particular, were near-contemporaries of Jaremtschuk, and in their art both were brutal critics of their culture and times. Unlike Jaremtschuk (who would have been only seven years old at its outbreak), Dix and Grosz experienced the First World War as soldiers, and Beckmann as a medical orderly. It was likely that the strength of their views and the forms of their visual critique were at least in part a result of the traumatic experience of war and the bloody social upheavals and privations that followed immediately in its aftermath in their native Germany. There is no question of Jaremtschuk knowing their work (or, incidentally, that of any other professional artists with whom we might draw useful comparisons). However, it would not be unreasonable to draw an analogy with Jaremtschuk’s experience in the labour camp and those other traumatic experiences of the three German artists two decades earlier. Beckmann’s Operation, 1914 shows the activity of a field hospital in a stern, matter-of-fact style, while Grenade, 1915 is a dynamic tumult of human life and death that is orchestrated around a fractured, spherical explosion of poison gas that mocks the life-giving sun that was common in pre-war Expressionist imagery. Dix’s series of etchings, War, started in 1924 is a powerful, nihilistic anti-war statement, derived from sketches he had made while serving as a front-line gunner. Though clearly in the tradition of Goya’s Disasters of War (1810-20), Dix’s works belong emphatically to the mechanized horror of the twentieth-century. Like Jaremtschuk, Dix is relentless in his visual critique and highly attentive to detail. His Seen on the Escarpment at Cléry-sur-Somme (Gesehen am Steilhang von Cléry-sur-Somme, 1924) places two mangled corpses in grotesque, silent ‘conversation’ with each other. In death they are startlingly reminiscent of some of Jaremtschuk’s foetid, disintegrating, figures in works such as Vomiting man with bandaged head (Fig.5), Killer in the doorway and Experiment. The big difference lies in the fact that Jaremtschuk’s figures are somehow still alive and, moreover, somehow still functioning.

Dix and Beckmann’s brutal matter-of-factness is transposed into a more stylized, overabundant critique of humanity in Grosz’s early mature work, which owes as much to street graffiti and lavatorial scrawlings as it does to Futurism or Expressionism. Yet, in its feeling for humanity – a kind of simultaneous outpouring of despair and misanthropy with real compassion and a lust for life – it seems to me closer in feeling to Jaremtschuk’s work. Most especially there is humour in Grosz and Jaremtschuk’s art, which is in short supply in that of Dix. Jaremtschuk’s humour – albeit at times sardonic or even diabolical – and his use of the language of the marketplace or the streets in the service of art bring me to one of his Russian near-contemporaries, the philosopher and literary theorist, Mikhail Bakhtin (1895-1975). His writing, and in particular his thinking around the notion of the «carnivalesque», can be usefully employed to help us understand further the worlds conjured up in Jaremtschuk’s art.

In Rabelais and his World, completed in the 1930s at the height of the Stalinist purges, but first published only in 1965, Bakhtin develops a theory of «carnivalized writing» that takes the «carnival spirit into itself and… reproduces, within its own structures and by its own practice, the characteristic inversions, parodies and discrownings of carnival proper»[2]. Bakhtin places laughter at the heart of his analysis, or more specifically, «the profound originality expressed by the culture of folk humour.» According to Bakhtin, in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance in Europe, «A boundless world of humorous forms and manifestations opposed the serious tone of medieval ecclesiastical and feudal culture»[3]. Carnival is a social inversion – the ‘World Turned Upside Down’, so to speak. As Andrew Robinson puts it: «A carnival is a moment when everything (except arguably violence) is permitted. It occurs on the border between art and life, and is a kind of life shaped according to a pattern of play. It is usually marked by displays of excess and grotesqueness»[4]. Moreover, says Bakhtin, «carnival... does not acknowledge any distinction between actors and spectators... Carnival is not a spectacle seen by the people; they live in it... While carnival lasts, there is no other life outside it»[5]. In many ways Jaremtschuk’s confinement, and more especially his artistic reaction to it, places him centrally within the realms of the carnivalesque. The world he creates is at once believable, yet hopelessly grotesque and extreme beyond almost all limits of human life, decency and ethics. Yet there are crazy laws here, nevertheless, and seemingly a system of moral codes that pertain only to the artist’s constructed universe... Or perhaps, more chillingly, the references are to Jaremtschuk’s actual, lived experience of the labour camp and hospital?

In Bakhtin’s critique the carnivalesque is articulated by a notion of «grotesque realism» that is centred on the body, and which he contrasts with the classical body. He regards the body in classical art as «finished, completed» and «cleansed, as it were of all the scoriae of birth and development»[6]. While the «grotesque body of Rabelais and the kind of art which he represents, appears unfinished, a thing of buds and sprouts, the orifices evident through which it sucks in and expels the world,» says Simon Dentith, «It is a body marked by its material origin and destiny»[7]. As Bakhtin himself says, the grotesque body «reflects a phenomenon in transformation, an as yet unfinished metamorphosis, of death and birth, growth and becoming»[8].

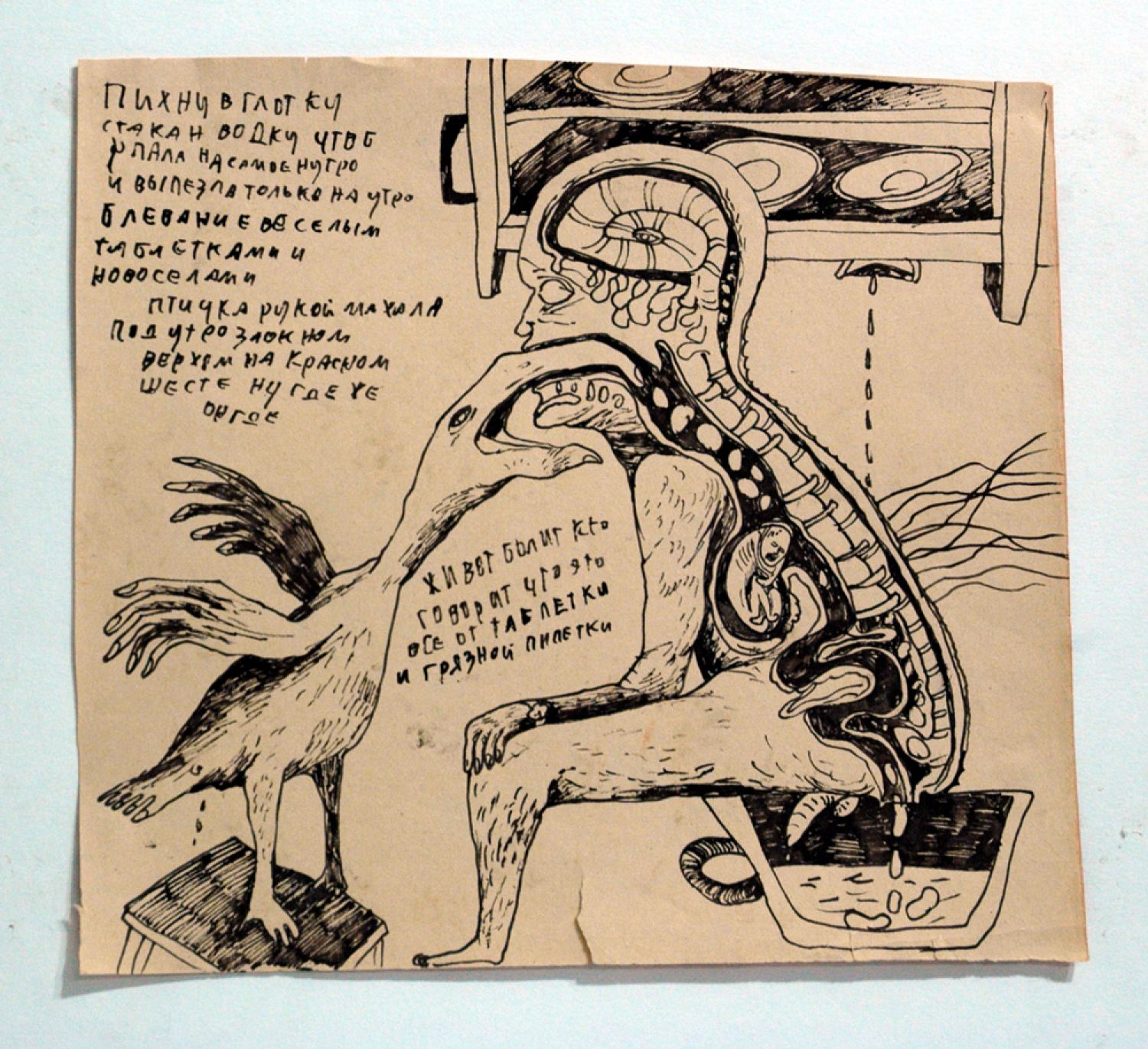

In Jaremtschuk’s work bodies are continually in processes of degradation. The closed bodily form in which individuals are normally bound and whose boundaries separate them from participating directly in the world of other bodies is constantly threatened. Bodily orifices are commonly emphasized, from an eternal procession of mouths gaping in silent screams (Mother and dead child), snarling (Avarice), or violently disengorging (Vomiting man with bandaged head), to countless defecating anuses (Latrine). Often, bodies are opened up with great sores, as in (Parasite), or pierced with vulva-shaped wounds, Prodding, (Fig.6).

Commonly bodily interiors are revealed, from the inside out, and intermingle with the world outside them.as in Flies came over the shit (Fig.7). Yet, these mutilated creatures still somehow live. Sometimes the depravity of this intermingling reaches Sadean depths, with those bodies representing power and terror unable in the final instance not to go beyond unspeakable violence and to begin to devour their victims (Powerplay, Fig.8).

All of this corresponds with Bakhtin’s description of grotesque realism:

«The grotesque body… body swallows the world and is itself swallowed by the world... This is why the essential role belongs to those parts of the grotesque body in which it outgrows its own self, transgressing its own body, in which it conceives a new, second body: the bowels and the phallus... Next to the bowels and the genital organs is the mouth, through which enters the world to be swallowed up. And next is the anus. All these convexities and orifices have a common characteristic; it is within them that the confines between bodies and between the body and the world are overcome: there is an interchange and interorientation»[9].

Yet we need to be mindful of the temporary condition of Carnival – it is the world turned upside down for only a short time and is, moreover, defined by acting; by play. Compare this to the permanent state of the culture of Jaremtschuk’s daily experience. Moreover, as Dentith points out, «carnival inversions... were clearly not aimed at loosening people’s sense of the rightness of the rules which kept the world the right way up, but on the contrary at reinforcing them»[10]. The ‘play’ that characterizes the carnivalesque is for Jaremtschuk a brutally serious business. If he evokes and enacts the spirit of carnival in his work, we must also recognise that it is the expression of a lived, continuous reality in which he is trapped.

Bakhtin’s thoughts on aesthetics are interesting in part because he is interested in the primacy of the creative process, rather than the object. «The basic assumption underlying Bakhtin’s work,» says Deborah Haynes, «is that the natural state of the world is mess. Order is not given, it is posited; that is, it is set as a task to be accompanied through work and especially through creative activity»[11]. In Jaremtschuk’s case we are presented with a strange mutation of this; his life from 1936 onward will have been defined by strict, imposed order that was, presumably, undesirable, and which strained in the everyday life of the interned community toward a return to ‘messiness’ that was also undesirable. As an artist he seems always to be engaged with this conundrum: how to fix and make sense of his own continued existence in the face of a doubly intolerable lived reality. In so doing, Jaremtschuk remarkably maintains a necessary «outsideness», as Bakhtin put it, to the subjects in his drawings; they «act», but he, as «author», is the category of «acting» that causes his characters to do as they do. Put another way, in each of his works Jaremtschuk’s «consciousness is the consciousness of the created consciousness»[12].

In spite of the horrors he describes in his drawings and even as they become manifestly more fantastic or hallucinatory in nature, for example, in Flies came over the shit (Fig. 7), And everybody feared and fell down out of joy (Fig. 9) and They mumble with toothless mouths (Fig.10), their very existence as contained, sealed and distinct objects in which the artist was not a central participant vouchsafed the integrity and continuation of his own unique, feeling personhood in its unfinalized condition. Bakhtin says our own outward body is always a mediated body, since we can only know it through inner states, and we can only encompass completely the body of the other. So, he says, «only I – the one and only I – can occupy in a given set of circumstances this particular place at this particular time; all other human beings are situated outside me... I am situated on the boundary... of the world I see»[13]. In creating works of art, Jaremtschuk controls and fixes the perceived world by externalising his feelings about it (and himself) in embodied form. One’s own completed, lived life is unknowable: «My birth, my axiological abiding in the world, and, finally, my death are events that occur neither in me nor for me»[14]. And in this sense, as Haynes says, «experience is infinite; it does not stop and I cannot stop being active in it. In other words, there can never be a completed memory of my own life for me, because it is ongoing. My own unity is never experienced as complete; it is always yet-to-be»[15]. For me writing now, and for Jaremtschuk making art as a living, embodied subject, there will always be a future. Each drawing, however, is a consummated thing; available to the viewer for memory, for imaginative re-enactment in its totality, and a confirmation to the artist of the reality of his own continued existence.

Though it is true that many people emerged eventually from Stalin’s labour camps, many others perished during their internment. In Jaremtschuk’s case, having endured confinement for more than a decade, which included a period of deeper privations caused by the Second World War, release from the labour camp in 1947 came only with his transfer to a Soviet psikhushka (psychiatric hospital), in which he remained until 1963. It was during the years he spent in this hospital that he produced the unique body of powerful art that concerns us here, and which seems to speak both to his contemporary experience of the hospital and his memory of the labour camp. Art produced in such conditions, where power relationships are so heavily weighted against the creating individual, is always precarious, and this work survived only thanks to his doctor preserving it. In 1963 he was transferred to another hospital. Though it is possible that he continued to make art, no drawings from this time have emerged. In 1974 Jaremtschuk’s condition deteriorated further and he was moved to a hospital for seriously ill and violent patients, where he died in 1986.

It is impossible to say when Jaremtschuk descended into psychosis, but it is clear that by the time he came to make these drawings he had transitioned to what the psychiatrist R. D. Laing called, «a psychotic way of being-in-the-world»[16]. It is likely that the trauma of life in the camps, including dehumanizing experiences that he will commonly have endured, as well as witnessing much worse, coupled with an authoritarian system that purported to see into the very souls of its subjects, would have led to a pronounced sense of vulnerability to his psychological as well as his physical being. It is interesting that individuals who have been reduced to dog-like creatures appear throughout his work, often crouching under tables or in the margins of scenes, greedily looking for scraps of food, as in Sing for your supper (Fig.11) and Soviet dogs. Similarly, characters are often opened up like medical illustrations, so that viewers (the authorities, the system, everyone) can see everything that is going on in the normally private interior of the body, both physically and in thoughts. So, in A bird was waving its hand in the morning outside (Fig.12), a defecating bird inserts its finger-like beak into a seated figure’s throat, down which pills visibly tumble. They pass a tiny, wretching creature in the figure’s stomach on their way, where they undergo transformation into stools that drop into the potty on which the figure sits. The text reads, in part: «I'll push a glass of vodka into my throat so it would fall down to the very guts and get out only in the morning... the stomach is aching who says it's all because of the tablets and dirty pipette».

Such «ontological insecurity» may render the subject «more unreal than real; precariously differentiated from the rest of the world, so that his identity and autonomy are always in question»[17]. It may be appropriate to think of Jaremtschuk’s psychosis in terms what Laing calls «engulfment». In such cases the subject is uncertain of «the stability of his autonomy», so that, «every relationship threatens the individual with loss of identity»[18]. Jaremtschuk’s response to such threats to his own selfhood was to deflect them by taking on and parodying in art works the characters of others who elicited in him fear and hatred. At a certain level this can be read as a carnivalesque de-crowning of authority figures, while at another, as Burkitt and Sullivan point out, parody «is used only obliquely against the figure of authority and appears as a desperate attempt to express feelings of hatred and despair without ever succeeding to dialogue with the authority figure»[19]. This is perhaps clear if we compare any of Jaremtschuk’s drawings with a 1938 account of conditions in the Bamlag camp by its chief procurator:

«In the infirmary, there are prisoners lying naked on long bunks, literally packed like sardines in a barrel. They are not taken to the bathhouse for weeks owing to the lack of underwear and bedsheets. In some rooms, women are lying on the bunks in the same room as men. A syphilis patient lies side by side with a tubercular patient. In a common room, there are patients with erysipelas (infectious) packed with stomach patients... Those who arrive have no underwear, nothing but rags. The terrible thing is that there is not a single change of underwear, boots, or clothes in the Bamlag. Their bodies are covered with scabs, but they do not take a bath, because they are not provided with underwear. Their tatters are full of hundreds of lice. There is no soap. Many have nothing to put on to go out to the bathroom»[20].

In many ways this account reflects the content of Jaremtschuk’s drawings. Yet it is also somewhat cool in tone and matter-of-fact. The drawings, however, present an overabundance of visual information that threatens to tip over (indeed, at times actually tips over) into fantasy, so that while their expressive and aesthetic force is undimmed, their believability as simple reportage is undermined. In this sense, whatever the artist’s intended purpose might have been for them, ultimately his drawings performed no practical beneficial service to his embodied person. As objects that existed in his life they were against him; that is, these carnivalesque parodies merely proved his ‘insanity’ to the very authority figures that were, in part, the subjects of the works. As art, though these drawings might yet prove to be widely celebrated by viewers internationally. The drawings’ work in our present (that is, their creator’s future) belongs to them, and it is only the memory of the now-consummated person, Jaremtschuk, that they serve.

It would be remiss to discuss the art of Foma Jaremtschuk and not think about it in the context of surrealism, the cultural movement which after all did the most to validate and encourage serious engagement with art made out of psychosis (though in its Parisian form, at least, it was also ironically enamoured for some time to Stalinism). The movement’s main leader and commentator, André Breton admiringly invoked 'madness' in the first Manifesto of Surrealism (1924) and elsewhere, and in 1965 he placed the artist, writer, musician, and long-term psychiatric patient, Adolf Wölfli (1864-1930) among the seven individuals (who also included Picasso and Heraclitus) who inspired the Eleventh International Exhibition of Surrealism in Paris[21]. It is impossible not to imagine that had he known of Jaremtschuk and his work, Breton would have seen enormous worth in it, in terms of both aesthetics and its ‘surreal’ content.

Breton was convinced that authentic creativity lay in the regions of our unconscious: «At these unfathomable depths there reigns the absence of contradiction,... a lack of the sense of time, and the replacement of external reality by a psychic reality»[22]. These depths could only be reached, he said, by in some way freeing oneself from the utilitarian regulation of conscious ‘reality’ through a «long, immense, reasoned derangement of the senses»[23]. Like Sigmund Freud, he believed that dreams permitted entry into these other regions, but that reporting back, so to speak, from dream reality was inevitably subject to conscious interpretation by the waking individual. «If the depths of our mind contain within it strange forces capable of augmenting those on the surface, or of waging a victorious battle against them,» he said, «there is every reason to seize them»[24], and he believed that ‘madness’ provided the only ‘authentic’ key to attaining the psychological liberation necessary to centrally occupy these depths:

«I have no hesitation in putting forward the idea, which is paradoxical only at first sight, that the art of those who are classified as mentally ill constitute a reservoir of mental health. This is precisely because it is wholly unaffected by all those considerations that tend to falsify the evidence which we others are preparing, considerations such as external influences, conscious calculations, success or disappointments encountered on the social level, etc»[25].

In this sense we might see Jaremtschuk as someone who was able, by virtue of his psychological condition, to penetrate mundane reality (as horrific and fantastic as this might have been in any case in the life of the labour camps and psikhushki) and report back, through his art works, the full extent of the psychic reality he endured. His hallucinatory figures and hybrid creatures are always placed in narrative situations that have a mundane, believability at their core: cooking, singing, working, defecating, treating, and experimenting. Yet it is like nothing we others looking at his work can compare to our own everyday experience. Metaphors are rendered real: There is a foetus in my skull that has replaced my brain, which the forceps-beaked doctor-bird will tear from me (Giving birth to thoughts), or Their faces merge into one and her stomach is a gaping, toothed vulva (Fig. 13), and I didn’t see anyone anymore. The insane are, says Breton, «victims of their imagination, in that it induces them not to pay attention to certain rules … which we are all supposed to know and respect»[26]. The result, though, in Jaremtschuk’s art, perhaps brings us close to a visual resolution of the contradictory states of consciousness and unconsciousness that Breton says constitute an «absolute reality», or as he would have it, a «surreality»[27].

The normalisation of the appalling living conditions of the labour camps and psikhushki that came with everyday exposure led Jaremtschuk to a kind of matter-of-fact aesthetic description that is nevertheless shocking to those who have not endured it; who have not occupied this life centrally. As the renegade surrealist, Georges Bataille notes: «what leads us astray is the too simple idea we have of cruelty. Generally we call cruelty that which we endure easily, which is ordinary to us, does not seem cruel. Thus what we call cruelty is always that of others, and not being able to refrain from cruelty we deny it as soon as it is ours»[28]. Attending to the drawings of Jaremtschuk is in some way like being witness to a ritualised destruction of self – the personhood of an other – from the inside out, so to speak, even as we remain bound in the bodies and social structures that render us whole.

So, once again, why are these drawings so compelling? Bataille might argue that they speak to an innate drive in all of us to know from the inside the condition of not-being. In this way their effect is analogous to his arguments about the function of torture:

«What we have been waiting for all our lives is the disordering of the order that suffocates us. Some object should be destroyed in this disordering... We cannot ourselves (the subject) directly lift the obstacle that ‘separates’ us. But we can, if we lift the obstacle that separates the object (the victim of sacrifice) participate in this denial of all separation. What attracts us in the destroyed object (in the very moment of destruction) is its power to call into question – and to undermine – the solidity of the subject»[29].

In an image like Terrible embrace (Fig.14) we are witness to the literal fragmentation and inevitable destruction of the central character. His sacrifice is not, incidentally, in the cause of some religious rite, but at the uniquely modern altar of science. Yet, says Bataille, only the «trap of death» is promised by sacrifice, «for the destruction rendered unto the subject has no sense other than the menace it has for the subject. If the subject is not truly destroyed, everything remains in ambiguity. And if it is destroyed the ambiguity is resolved, but only in a nothingness that abolishes everything»[30]. In Jaremtschuk’s drawing the fragmenting bodily states of the semi-human female scientist/torturer and assistant of indeterminate gender, together with the wilful, intrusive tasks in which they engage, emphasises precisely the ambiguity that lies between their own continued existence and the threat of non-life. And the enactment of their roles in the image points strongly to the likely existential state of the central subject being the exact, liminal moment of his death. The thick, jagged lines that stream from the woman’s eyes and mouth into the scientific machinery seem to be sound and sight made tangible, confirming the significance of the moment. And that, in general, argues Bataille, is the source of art’s power: «it is from this double bind that the very meaning of art emerges – for art, which puts us on the path of complete destruction and suspends us there for a time, offers us ravishment without death»[31]. This is what Bataille means when he claims that, «When horror is subject to the transfiguration of an authentic art, it becomes a pleasure, an intense pleasure, but a pleasure all the same»[32].

This uniquely important body of work could so easily have been lost. Its creator was not a professional artist. Indeed, Foma Jaremtschuk knew nothing of art worlds, movements or artistic careers. But, like any artist worthy of the name, he was driven to make work by some compulsion, rather than through mere choice. The circumstances in which he produced his art were conducive neither to the pursuit of an artistic vocation nor to a wide, appreciative reception. If his work was valued, then it was more likely for its interpretive use by doctors, seeing image and text as symptomatic of the artist’s illness, rather than as aesthetic object. This is probably the primary reason his drawings were preserved at the time. So they did survive. And for long enough to be recognized as art. For all of these reasons, Jaremtschuk’s drawings can also be seen as part of the field of Art Brut, or what has come to be known in English as Outsider Art[33].

It is too easy to imagine a world divided into trained professional artists and amateurs. Unlike the former, amateurs are dabblers; they might derive great satisfaction from art-making, but they have another life that is the one that takes up their workaday existence and defines them. Jaremtschuk fitted into neither of these formulations. Though not part of any professional or amateur artistic structure, the need to represent his world in image and text occupied the centre of his being. Cut adrift, so to speak, he represents a familiar story of Art Brut, which is art of high aesthetic worth that is content-laden and speaks forcefully to its subject matter. It speaks in an intuitive tongue that is accessible to all, but only when approached in a spirit of openness and without preconception. The French post-surrealist artist, Jean Dubuffet, who invented the term in the mid-1940s, went as far as to argue, polemically, that Art Brut was the only really authentic art of his time. «True art always appears where we don’t expect it,» he said, «where nobody thinks of it or utters its name.» It is art produced by «persons unscathed by artistic culture»[34] who have «succeeded in freeing themselves from cultural magnetization» and rediscovered a «fecund ingenuousness»[35]. There is an enormous wealth of art that comes from ‘unlikely’ places. Much of it emerges out of traumatic experience, as Daniel Wojcik has shown[36]. Jaremtschuk’s project saw him overcoming an intolerable existence by engaging with it head-on through art making.

–

Images: all images are Foma Jaremtschuk, ink on found paper. Precise dates are unknown, but the portfolio was produced sometime between 1947 and 1963. The works are not titled by the artist. All titles are mine. Where possible I have taken the title from text written on the drawing sheet. Images are courtesy Henry Boxer Gallery, London.

Curatorship by Katherine Sirois

Footnotes

- ^ Andrei Vishinsky, quoted in Jonathan Brent, Inside the Stalin Archives. New York: Atlas and Co., 2008, p. 12.

- ^ Simon Dentith, Bakhtinian Thought: An Introductory Reader. London: Routledge, 1995, p. 65.

- ^ Mikhail Bakhtin, Rabelais and His World, trans. Hélène Iswolsky. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1984, p. 4.

- ^ Andrew Robinson, «In Theory: Bakhtin: Carnival against Capital, Carnival against Power», Ceasefire, 9 September 2011. https://ceasefiremagazine.co.uk/in-theory-bakhtin-2 visited 17 March 2017

- ^ Rabelais and His World, op cit., p. 7.

- ^ Ibid., p. 25.

- ^ Dentith, Bakhtinian Thought, op cit., p. 67.

- ^ Rabelais and His World, op cit., p. 24.

- ^ Ibid., p. 317.

- ^ Dentith, Bakhtinian Thought, op cit., p. 74.

- ^ HAYNES, Deborah J. (1995) Bakhtin and the Visual Arts. Cambridge University Press, p. 66.

- ^ Ibid., p. 72.

- ^ Bakhtin, as quoted in HAYNES, Bakhtin and the Visual Arts, op cit., p. 76.

- ^ Ibid., p. 125.

- ^ HAYNES, Bakhtin and the Visual Arts, op cit., p. 126.

- ^ LAING, R. D. (1990) The Divided Self. Harmondsworth: Penguin, p. 17.

- ^ Ibid., p. 42.

- ^ Ibid., p. 44.

- ^ BIRKITT, Ian and SULLIVAN, Paul. (2009). «Embodied Ideas and Divided Selves: Revisiting Laing via Bakhtin». British Journal of Social Psychology. 48, p. 572.

- ^ As quoted in BRENT, Inside the Stalin Archives, op cit., p. 13.

- ^ See BAUMANN, D. «The Reception of Adolf Wölfli’s Work, 1921-1996» (in SPOERRI, E. ed. (1997). Adolf Wölfli, Draftsman, Writer, Poet, Composer. Ithaca: Cornell University Press), p. 217.

- ^ BRETON, André. (2002). Surrealism and Painting. Boston: MFA Publications, p. 70.

- ^ BRETON, André. (1972). Manifestoes of Surrealism. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, p. 175.

- ^ Ibid., p. 10.

- ^ BRETON, Surrealism and Painting, op cit., p. 316.

- ^ BRETON, Manifestoes of Surrealism, op cit., p. 5.

- ^ Ibid., p. 14.

- ^ BATAILLE, Georges. (1949). «The Cruel Practice of Art». At http://supervert.com/elibrary/georges_bataille/cruel_practice_of_art, visited 16 March 2017, p. 3.

- ^ Ibid., p. 5.

- ^ Ibid., p. 5.

- ^ Ibid., p. 5.

- ^ Ibid., p. 2.

- ^ For a short account of the history and definitions of the terms ‘Art Brut’ and ‘Outsider Art’ see my ‘Outsider Art’, Encyclopaedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/art/outsider-art, visited 21 March 2017.

- ^ DUBUFFET, Jean. ‘Art Brut in preference to the cultural arts’. In WEISS, A., ed. (1988). Art Brut: Madness and Marginalia. Art & Text (Special Issue). 27, p. 33.

- ^ DUBUFFET, Jean. ‘Make Way for Incivism’, in WEISS, Art Brut, op cit., pp. 34-35.

- ^ WOJCIK, Daniel. (2016). Outsider Art: Visionary Worlds and Trauma. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.